Web

and Book design, Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |  (HOME) |

THE TREES OF

MAINE WE suspect that

when Maine was called the Pine Tree State, the word pine was made to do

duty in

a general way for evergreens. we know that much furniture, said to be

pine, is

often spruce or cedar in parts. There is a loose manner of thinking of

all

evergreens when wrought into lumber, as pine. whatever may once have

been the

case, we very much doubt whether the pine is now the predominant tree

of Maine.

A lady of some discrimination declared to the writer that she journeyed

over

two hundred miles in Maine without seeing a pine from her car window.

We wonder

whether she might not have taken at least a few naps. A surprise,

however,

awaits the traveler who supposes that he is about to drive through

interminable

pine forests. The spruce is very much in evidence, fir is common,

hackmatack

usual, and hemlock more than common. Perhaps a pine,

at

its best estate, is the most picturesque of trees, but it is seldom

that great

pines are symmetrical. The gnarled growth of a pine may be more

picturesque,

but it is a question whether the pure beauty of a perfect cone is not

more

attractive. while it is doubtless true that the pine was culled out

near the

shore, it probably was never as predominant as it was popularly

supposed to

have been. The most

valuable

wood economically in Maine is perhaps the spruce. It is being cut away

so

rapidly that without careful restrictions the state is likely to be

denuded.

The spruce is a tree of very great beauty both as to color and form. It

is also

an ideal wood for ship spars as well as its more common use for paper

pulp. In

its different varieties it is found almost everywhere in Maine.

Evergreens are

found more particularly on a light soil. It is, indeed, a very happy

provision

of nature that pines will grow in almost pure sand. we have seen

splendid

forests of pine on land worthless for anything else. The fact may serve

to

bring out what modern science has shown us, that everything can be

used. There

are no barren soils, especially in eastern America, since we find here

no

deleterious chemicals in the soils, and every bare tract can be

converted into

a valuable plantation. The importance of pine is on this account coming

much to

the fore just now. A curious

condition

regarding tree growths is that trees growing in the open, with limbs on

all

sides, are of small value commercially, while esthetically they are far

finer

than forest trees. Indeed, a lone tree, left after the forest is cut

away from

it, is rather unsightly, since it has only a small tuft in the way of

foliage.

We are indebted to the darkness for the goodness of timber. In the

forest the

lower limbs cease to develop and leave no trace except small knots. Yet

we have

an admiration for the beauty of forest trees, since they complement one

another, growing in the mass. Their foliage is so far away that we hear

only a

distant sough. We walk like pigmies among the mighty boles, and lay our

hands

affectionately upon them. Sometimes, even in the deep forests, the

ferns make a

fine growth. Near Moosehead Lake we came upon a good half acre of

maidenhair

ferns, the most extensive tract we have observed. Near the streams,

also,

either on the trees or on the rocks, within the reach of wind-blown

spray, fine

mosses thrive, and we have shown a detail of such moss, on the banks of

the

Penobscot. The fir tree is

not

very familiar in the lower temperate zone. Its foliage somewhat

resembles the

hemlock, except that the short needles grow out in every direction from

the

stem. The rich color and the exuberance of the foliage has a fine

effect. This

is the tree which supplies the balsam so highly regarded in the last

generation

as a pulmonary remedy. The odor of the balsam is still supposed to be

healing.

Whether, there is a direct benefit, or that better indirect benefit

derived

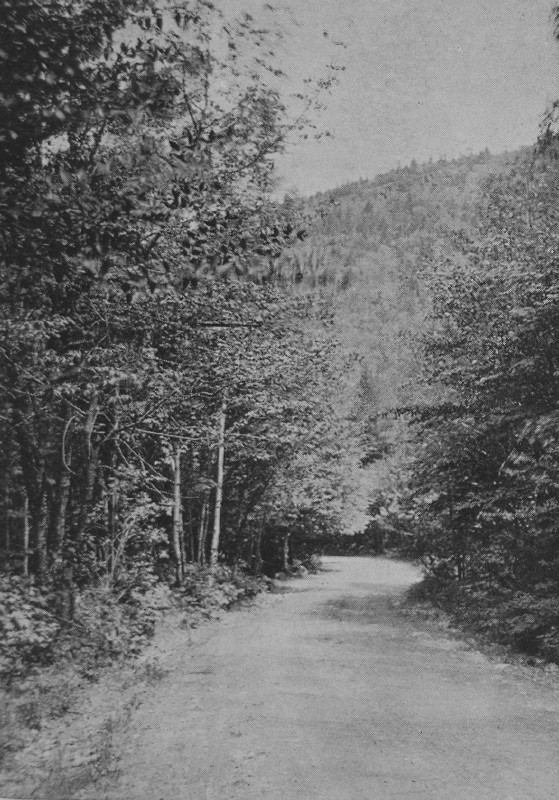

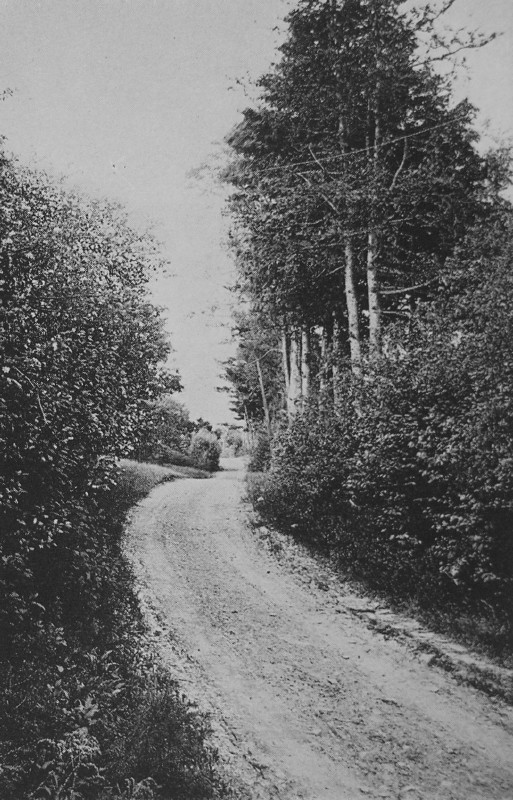

from wandering in the forest and living outdoors, we do not know. The gums of evergreens, especially the spruce, are best collected where, as not seldom occurs, a lightning stroke has left a long seam in the bark from top to bottom. In this wound the tree exudes its gums to save itself, and affords a fine harvest for the gum hunter. At first the crystal globules are mere pitch, and it requires some years for them to become good gum. A QUAINT OVERHANG, PORTLAND-STANDISH ROAD The interest of a forest lies largely in the superimposed growth. The ancient trees that have fallen and gone back into the soil are the source from which the new growth arises. Where this process is often repeated, we obtain the fine depth of wood-mold so stimulative to plant growth. It affords no end of sweet imaginings to see a recently fallen tree lying upon another that is moss and punk, while this tree, in turn, rests upon still another which has wholly disintegrated. It is not often that forest fires have allowed this condition. It is the underlying punk wood which carries the fires, sometimes for a half mile, in a wholly invisible manner. The flame will then break out again at great distance. This is why fire fighting is so difficult, dealing as it does with an elusive element in an ancient wood. The old punk burns like a slow match, with a dull glow. We suppose that the cigarette smoker will continue his vicious habit, until the time comes, as it may in some generation, when men seek higher pleasures than that of nicotine. The campaign against fires is pretty vigorously waged, by warnings to extinguish all camp fires, but so long as it does not constitute a crime to smoke cigarettes, little headway will be made.

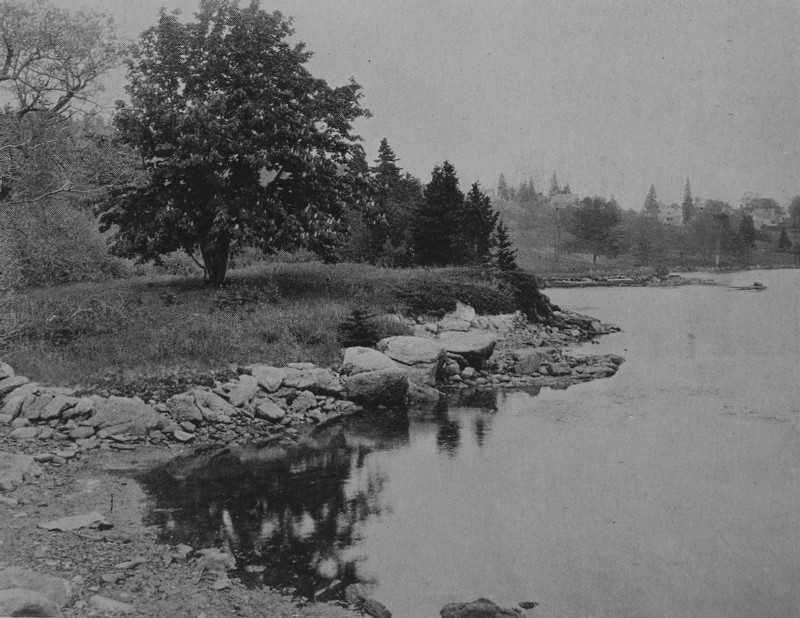

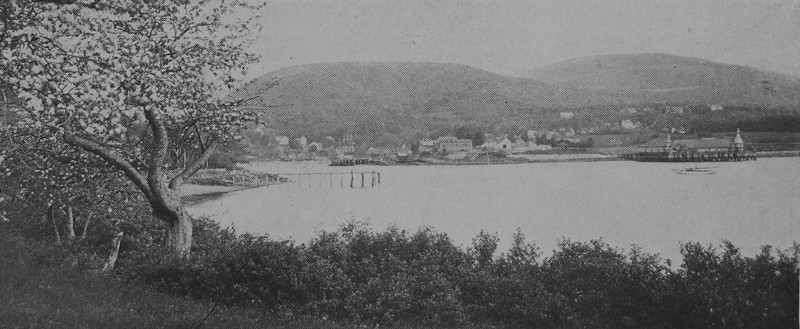

A SUMMER SHORE - NEAR BATH  AWAY DOWN EAST - DRESDEN  A CRYSTAL LANDING - GRAY  CAMDEN HARBOR  SABBATH DAY LAKE - NEW GLOUCESTER  BIRCHES IN SUNLIGHT - CAMDEN  A SABATTUS SHORE  THE RIPPLES' EDGE  UNDER THE CREST - CAMDEN  AT LEISURE - CAMDEN  THE BOAT UNDER THE BOUGH - WISCASSET  A DIVING POOL, CRYSTAL LAKE - GRAY  FERN, BLOOM AND ELM - DRESDEN There is

something

back of forest fires that lies in uneducated natures. There is an

abundant

number of city people who seem to recognize no property rights in the

country.

They freely break down lilacs and the blossoming boughs of apple trees,

and

make use of the land wherever their fine fancy prompts. They could own

this

earth on which they tread for a very small investment. They prove,

however,

that their interest is not serious, and their admiration not honest.

The love

of nature is shown by the respect we show to her. To build a fire

against a

dwelling is not nearly so dangerous as to build a fire in the forest,

unless a

site with wide areas of clean earth surrounds the blaze. A forest fire

is like

a bitter word, left to rankle. when we consider the slowness of the

growth of a

character or a tree, it is no less than a miracle that we have good men

and

good trees. The Indians were accused of setting fires for various

purposes, in

the old days. Sometimes they wished to drive out game; sometimes they

wished to

encourage the growth of grasses or shrubs for deer and moose to browse

upon.

But since they used little timber, in their crude civilization, they

were not

as blameworthy as the present day barbarian who is destroying the

ancient

forest. Nothing is more unsightly than a burned-over tract. Nothing is

more

delightful than an undisturbed woodland. We are slowly learning that to

call a

man civilized does not make him so, and that the savagery of the

twentieth

century is far more dangerous, and in many instances more complete,

than was

the case before the days of Columbus. If we can't be lovers of beauty,

let us

at least try to be decent in ourselves. Fire does not belong to us by

any right

that we can claim as human beings. Nothing belongs to us. We take

everything on

sufferance. Even when we buy, we simply enter into an agreement with

another

man to quit his claim to the thing we purchase. Back of his claim is no

indefeasible

right. We may get our deeds from the Indians, but judgment on us for

our use of

the lands is decided by an older and mightier power. Twenty thousand

acres have

just been burned over in Maine, as we write. The state pays a great sum

to its

fire fighters, and in addition it suffers the loss of its forests and

its

reservoir of waters. That a characterless man should handle carelessly

the

mystery of fire is one of the anomalies of civilization. The hackmatack,

or

American larch, is one of the anomalies among trees. Though a conifer,

it is

not evergreen. The irregularity of its branches gives it an airy grace.

We have

not seen elsewhere than in Maine rows or clumps of hackmatack planted

as

windbreaks or decorative trees. Occasionally one sees a whole forest of

them,

usually on the lowlands. The hemlock,

much

despised in the early times, is so common that it is now much used as a

cheap

lumber, though it affords shaky boards. In its growth, it is often

graceful.

One of its important values is its bark, used for tanning, though the

oak bark

is better, and modern chemical methods are likely to supersede both

barks, and

leather itself, for that matter. The poplar is another common wood, cut for pulp or for spools. We were accustomed to think of it as a somewhat plebeian tree. Now, however, when we see the hard woods, such as maple and birch, passed over as valueless in the back forests, we must revise our opinions. It is said that a quarter of a million cords of pulp wood will be floated this year, down one branch of the Penobscot river. It is surprising to see how well trained the sticks are, keeping generally in the middle of a strong current, where the stream is of fairly uniform width. In the broads, however, and where the eddies form, it circles about several times before it is willing to proceed. In times of high water, tossed up on the bank, it remains, and in parts of the river shows a definite line of numerous sticks on the sands or the crags. From these positions it is cleared every year or two, in the autumn, by a process called "picking the river." Beginning at the highest and most remote tributary streams, every stick is started on its way by the deft river man, and followed down until millions of feet are gathered at the final point. The life of the river men, while dangerous, is not so much so as it appears, to one who watches them from the bank, leaping from log to log. PEMAQUID FORT The workers at

this

trade acquire a love for it. In fact, it would seem that the more

dangerous an

occupation out of doors, the more ready are men to go into it. This

promises

well for a hardy race. So long as men are ready to take up dangerous

callings,

which nevertheless give health and quick, iron muscles, it indicates

that the

spirit of manhood is not on the decline. The life of the camp has

developed a

type. The food is of the best, but woe to him who finds fault! By the

discipline of the camp, the critic or the cook must go, and it is not,

as a

rule, the cook. The quantity of food consumed is enormous, since the

activity

of the lumberman and the cold weather require great interior fires. We

have

heard of one foreman who rapidly took on board nine fried eggs, as the

introduction to his breakfast. In addition to the meats, of which there

are all

sorts, and all good, there was at least one instance when rich baked

beans were

also served for three hundred and sixty consecutive meals. This is the

total

number of meals during which the cook-house was in operation. Do not

imagine

there was a change in diet. In putting up dinners for the men who go

too far to

return for them, there were, in this camp at least, always added a

dozen

cookies, besides the dessert. A cook informed me that such trifles do

not

count, and that he never knew a cooky to be returned.

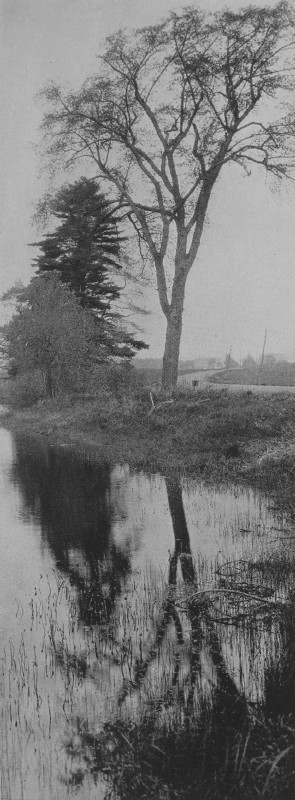

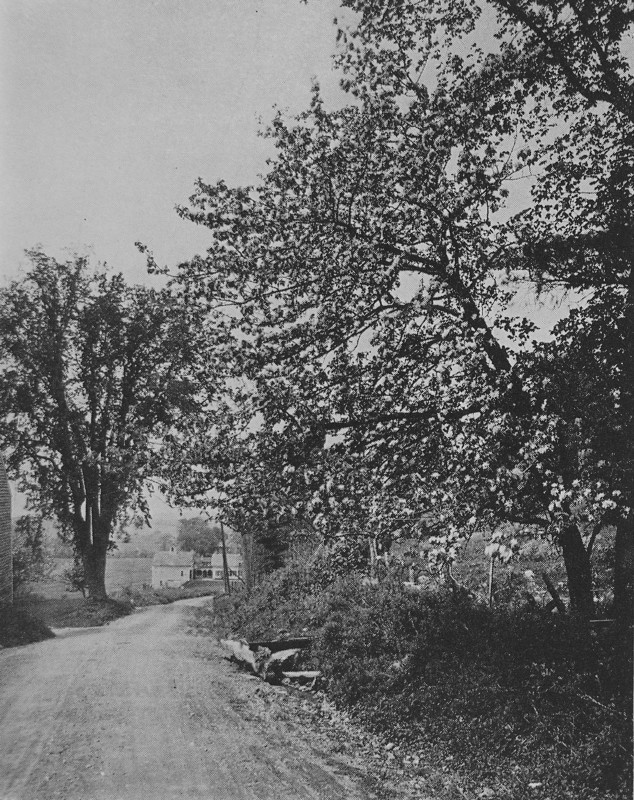

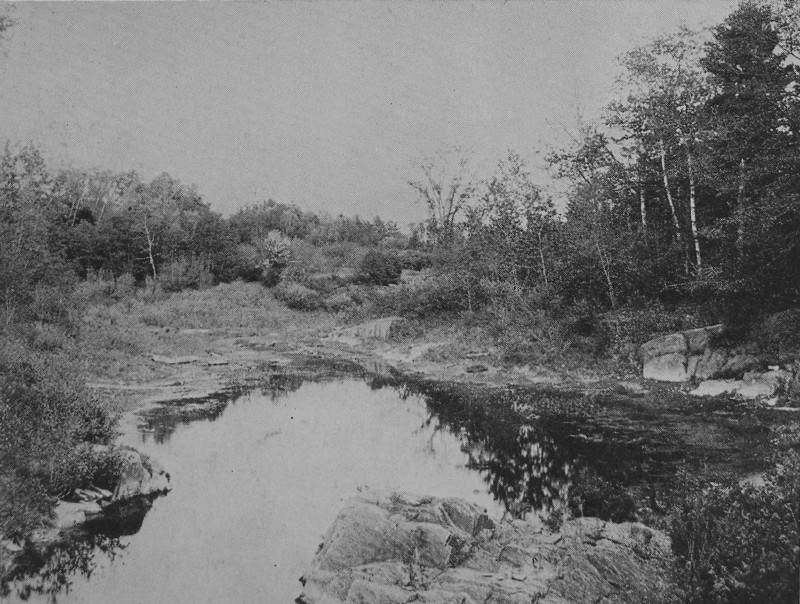

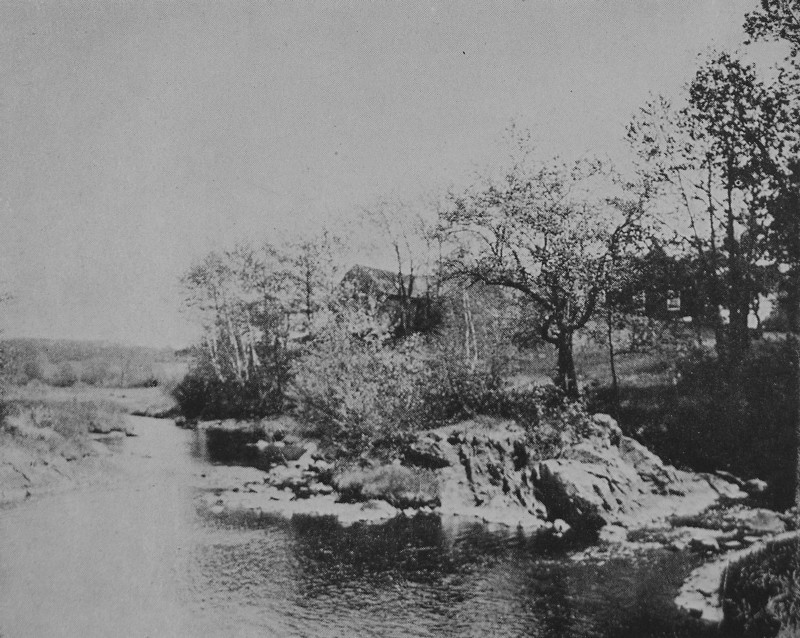

POLAND SHADE  THE RIPPLES' EDGE - WISCASSET  THE SWIMMERS' DELIGHT - DANVILLE  TOPSHAM BANKS  MEETING THE TIDE - ROCKPORT  THE ROADSIDE TROUGH  INTO THE VALLEY - EDGECOMB ORNAMENTAL AND FRUIT TREES THE maple and

the

birch and the elm are the usual trees along the walls. The elms, though

not so

old as those of Massachusetts, are scarcely less majestic. In many

towns they

form a wonderful canopy over the streets. In the smaller places, as

Randolph,

Dresden, Union, and a hundred others, their great trunks lend dignity

and

character. The maple is a

favorite, largely, probably, because of its quick growth. It requires

but a few

years to cast a dense and broad shade. This very early maturity,

however,

betokens an early decay, as we have elsewhere pointed out. The basswood

is in

some neighborhoods a favorite. The buttonwood scarcely occurs in Maine.

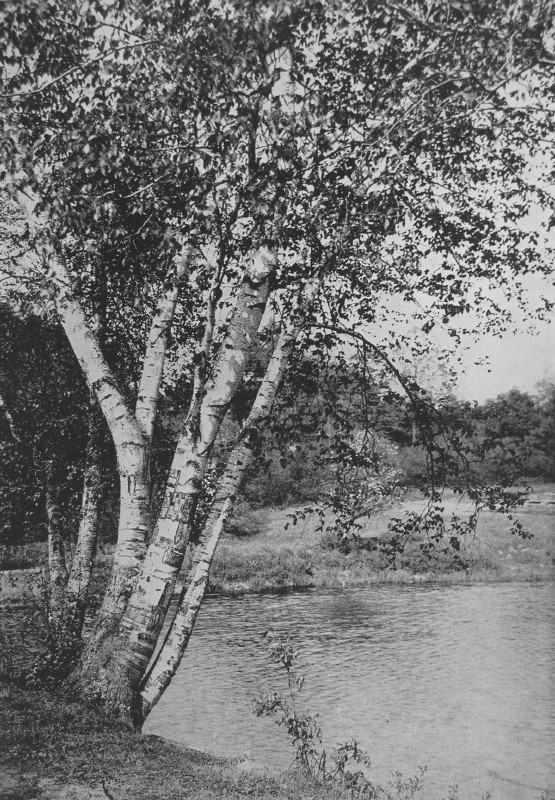

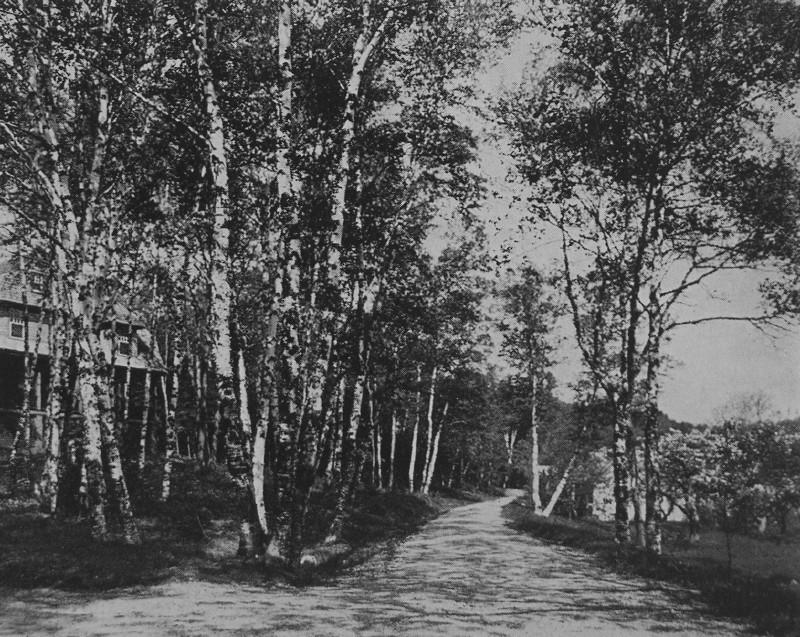

The birch tree,

with its velvety pink bark, of the sort growing in northern latitudes,

flourishes in Maine very extensively, though there are regions where we

see it

seldom. When at its best, it has an individual charm unlike any other

species.

we have been happy in finding at York and Damariscotta, in New Vineyard

and

other quarters, a large number of delightful specimens or groups of

these

trees, which light up the twilight roadsides and form an artistic

marker. The

great wood piles of white birch are a feature of the farmhouses. At

Lincolnville, the children of a family built them a fort in the

woodpile, while

the buttresses were round sticks with their white rims, and the guns

were large

and fine salmon-colored logs. The bright eyes of the defenders peeped

shyly

over their ramparts. we left them as dangerous persons, who would

captivate our

hearts and keep us in bondage if we remained long. The beech woods

of

Maine, always winning us by their fine trunks, supply another source of

fire

wood. The oak is not so common nor so majestic as we find it in

Connecticut.

The distinctive and frondlike foliage of the locust appears here and

there,

and, of course, the horse chestnut is highly honored. The nut trees of

Maine

are confined mostly to the beech and a few sporadic specimens of other

varieties. Beach nutting was the usual excuse in the autumn for a

frolic in the

woods. The cherry

trees of

Hallowell, of the great blackheart variety, were long a well-known

product. The

wild cherry remains as a pest of the wayside, since it is a dangerous

and

favorite host for worms. Since the wood is of some value for furniture,

a

campaign ought to be begun against all wild cherries. This tree is

quite

distinct from the sour cherry of Pennsylvania, so much cultivated for

its

fruit. The choke

cherry,

so appropriately named, is another product, almost as dangerous as

poison to

the small boy. It remains for some genius to find a use for its fruit. The roadsides

of

Maine are beautiful in the autumn with the elderberry, growing by the

stone

walls and ancient fences. Wild blackberries grace the spring and enrich

the

autumn. The upland pastures and roadsides are well spattered with

raspberry

bushes.

THE love for apple blossoms, which has become so evident in the writer's life, seems never satiated. This year has been wonderful for the fullness and general diffusion of these pearl-white, myriad petals that fill the air with fragrance and the eye with delight. To this we must add that by rough computation, carried on throughout the spring, we determine that at least nine out of ten orchards in Maine are neglected, and more than half of them grossly neglected. The apple is alive only through its own persistence. There is no general sorting or rating of the fruit. The Maine apple is equal to any that grows and superior to all that grow south of it, hard and luscious even into the spring, when we so much crave its deliciousness. It exists on tolerance, without half a chance. Here and there, as in Monmouth, there is serious attention paid to it. we have in mind an orchard that once made its owner rich, but that is dying now that he has died. The juniper and the evergreen, beautiful but fatal, are springing up to choke out the forlorn trees, many of them not past a rich usefulness. If one-half of the skill or enthusiasm that we see in California were devoted to the Maine apple, it would be grown in the greatest profusion and would make its qualities widely known. Emphasis should be placed on the keeping qualities of these apples. It would be easy to prove, by the fruit itself, how superior it is to that brought from the west. We have seen in northern Maine cities, in the fruit shops, great quantities of mealy, tasteless western fruit, that sold purely for its skin-deep beauty, while the unsought, but delectable native fruit could not be had except on insistent demand. The crying need of Maine, at the present time, is first a belief in its own products, and then the fostering and exploitation of them. Great areas in Maine, where the soil is somewhat light or gravelly, are perfectly adapted for successful apple culture. Strangely enough, we note many apple orchards on heavy clay soils. Some farms have no other soil. If apples will flourish under such conditions, how much more might they be a source of delight and profit on those farms which at present yield a meager living. Along the shores of Maine, and all about the lakes, apples thrive. They seem to delight in slopes above water. THE SPARHAWK HOUSE HALL, KITTERY We have been traveling in Elysium for months this year. The blossoms have told their silent story most eloquently. They came late, but lasted long, and many a tree seemed bent on outdoing itself. At least, it was bent! Never have we seen so many great branches sweeping the ground. Redolent, multitudinous, aromatic, the delight of the hillside, the fence corner, the gable of the shed, and the roadside, it has filled us with joy. The apple blossom is the most attractive form of prophecy. If asked if we believe in prophecy, we answer, yes. Shall not the intelligent men of Maine protect these blooms from blight, and meet half way this most luxuriant and beautiful overture of God to men? THE SPARHAWK DOOR, KITTERY Among the

hundreds

of blossoms, the pictorial record of which we have made, we find

ourselves in a

delicious uncertainty which to choose. We have therefore laid the

abundant

feast before the reader. Eat, and be filled! We must, however, say that

the

view of a gable decorated by blossoms at Edgecomb, where we looked down

upon a

bay, was among our finest experiences. Again, where we looked up at the

old

block-house through wild-apple blossoms, we felt that charming

combination of

youth and age, of which the world never tires. In an orchard in Camden,

while

we were making adjustments for a picture, we found a wood snake twined

about

the post of the camera, and within striking distance of our eyes. This

is the

only instance in our experience of a serpent's interest in art! The

poor,

harmless creature, he has gone the way of all snakes! The pyramidal form of the pear tree and its early bloom give variety and a longer term to the white billows of the spring. This year also, for the first time, we have found the wild cherry of use, peeping over its diffused abundance from the shores of Boothbay. We have also made our initial studies of effective horse-chestnut blooms, and have recorded the dogwood in its luxuriant and widespread brilliance.

THE steadiness of the Maine winters, in spite of exceptional January thaws, provides good sleighing. The modern method of rolling the roads affords a very much better surface than we used to enjoy. In some parts of the state, as on the fine route from Greenville to Ripogenus Dam, a sprinkler is sent over the road after it is rolled. The result, so far as the ease of gliding is concerned, can hardly be understood by those who have not had a recent sleigh ride. For sleigh riding is the king of winter sports, because it may be so generally enjoyed, and enjoyed for so long a period. We have shown two or three pictures in this work of ski jumping and snowshoeing, furnished us by the courtesy of the Maine Publicity Association. The modern tendency in sports seems to be for a few to enjoy them by actual participation, while the many stand about in the cold. In this respect we think the old way was better. Then everyone participated. It would have been a poor creature, subject to raillery, if not contempt, who would in those days have stood at the side of the road while the coasters went by. Any girl is pretty in the winter, with her pink cheeks. It would have been an exceptional girl for whom no place was made on the double-runner. THE SPARHAWK HOUSE PARLOR, KITTERY While perhaps

we

strain a point if we reckon gathering maple sap as amongst winter

sports, we

nevertheless considered it in that light in our childhood. Two

pictures, one

showing the sap house, and another the gathering of the sap, were also

furnished us by the same source. Undoubtedly it

is a

good thing to induce city people to go into the country in the winter,

though

it should require no inducement, other than the splendid tonic of the

air, the

sparkling snow on the hills, and the winter festoons over the fence

rows and

the farm buildings. Any measure that tends to call the attention of the

public

to winter as an asset, rather than a liability, is commendable. Maine

offers

the only large area in the east open to settlement. Many persons from

northern

Europe settle in the Dakotas and contiguous states. In Maine they might

enjoy

the windbreaks supplied by the fine forests, and the ranges of hills.

They

would be certain of a crop, and would not require the weather bureau to

tell

them whether enough rain would fall. Maine has never called on the

outside

world for food. She has enough and to spare, and in sufficient variety,

so that

life is still agreeable on many thrifty Maine farms. We have this year

visited

such farms where optimism was a habit, and where plenty abounded. If

those

persons who sometimes go under the name of radicals, were to study the

methods

of the successful farmers in Maine, they would not require to press for

laws asking

farmers. bonuses. Maine is one of two states in New England where

farming is

still carried on extensively and seriously, with the idea of obtaining

one's

whole living from the land. Bangor is no colder than Burlington.

Probably the

thick blanket of winter snow in Maine is in part accountable for the

sweetness

of the corn which has given that product supremacy in the markets of

the world.

Everywhere, we think without exception, races who have made good where

cold

winters occur, were good races, in the sense that they possessed good

physique,

persistence, thoroughness, stability, and in general, admirable

characters.  A DRESDEN RETREAT  FROM ANOTHER CENTURY - RICHMOND  OVER THE HILL - DRESDEN  ALL JOY! - DRESDEN  A WILDWOOD DELL - ALNA  POLAND SHADOW PLAY  INLET AND OUTLET - BIDDEFORD POOL  A

CAMDEN ARCH

ATTRACTIVE

MAINE

VILLAGES EXCURSIONS

ending

at the point of departure from many Maine

villages and small cities may be made very attractive.

From Fryeburg one

is under the shadow of the White Mountains. A route north past upper

Kezar Lake

is altogether beautiful. Roads easterly skirt fine streams, and roads

southeasterly pass through evergreen woods. Fryeburg is of the right

size, and

its people are of the character, to give pleasure in such summer

acquaintances

as may be formed. The Saco, in its quiet stretches, is nowhere more

beautiful

than from the bridge nearest the village, though there are two other

bridges

somewhat farther away which show the stream in much beauty. A great

boulder in

this town has the reputation of being one of the largest known. At

Lovell's

Pond, also, is the site of an old Indian battlefield. The pleasantest

summer of

the author's youth was at Fryeburg, how many years ago we don't care to

say. We

will say, however, that a week's exploration over the old haunts this

summer

afforded all the joy of the past. Bethel is a

village

quite given up to summer visitors, and abounding in attractions. The

Androscoggin shows us here many fine curves. The stream which flow into

it are

even better. One of these we regard as almost the most beautiful of our

Maine

discoveries. The location of Bethel, accessible from many other

interesting

points, must continue to foster its popularity. Farmington has

for

many years enjoyed distinction for its quieter surroundings near the

upper

Kennebec and the Sandy river. Its intervales mark the appropriateness

of its

name. Its old and notable school supplies an atmosphere agreeably

classic. Guilford is a

large

village close to some of the most distinguished lake scenery in New

England.

Its river also is not without many windings, punctuated by the grace of

elms. Foxcroft-Dover

is

in a region more completely given up to open land farming. It is a good

type,

if we may use the pronoun "it" of a twin settlement, where a certain

amount of manufacturing in a market town diversifies the life of the

people. Newport is a

meeting place of roads and the base for visiting the beautiful shores

of

Sebasticook Lake. It is prepared to entertain visitors who go away with

pleasing

impressions of an open landscape without great inequalities of

elevation. The

same may be said of Skowhegan and Phillips. Phillips, however, is not

far from

distinguished mountain scenery. Saddleback attains the respectable

elevation of

four thousand feet, and Mt. Abraham is almost as lofty. Wilton, with

its pond

and its background of hills, is a village which, together with Weld,

also

supplied with a fine body of water, may attract the guest. Indeed, both

these

towns have that beauty of which we never tire, the conjunction of

mountain and

lake. Mt. Blue, near weld, was for long a favorite resort in blueberry

time, so

much so that in our childhood we supposed that blueberries were named

for the

mountain! Belgrade has

become

a famous lake center. Its proximity to Augusta and Waterville has been

availed

of locally, and visitors from afar swarm in the region. The town of

Rome, which

was once synonymous for rocks, now has a broad highway through it from

Augusta

and Waterville to Farmington, and its sharp hills have become a joy.

The lakes

of Belgrade have so many intricate windings and touch one another in

such

unexpected fashion, that those who sail upon them would require years

to feel

at home, and even then losing the sense of newness, they acquire the

sense of

familiarity which is even dearer. The lakes of

Winthrop have long been a favorite resort from the cities of the

Kennebec and

from Lewiston and Auburn. The road to these lakes in spring or autumn,

whether

in blossom time or in the time of painted leaves, is equally enjoyable.

Cornish, while

mainly perhaps thriving by its industries, and as a local market, is a

very

pleasing headquarters on the Saco, for excursions, in which may be

included

Sebago Lake. Everybody knows the water centers of Bridgton and Naples,

and the

features of Poland are too distinctive to require elaboration. we have

been

happy in finding pictures of fine woodland drives in this vicinity. We have already

mentioned, though our minds constantly revert to, the charms of

Wiscasset and

Damariscotta. If we were to speak of a red letter day in Maine, perhaps

the

most enjoyable we have had for years, we should say it was a spring day

in and

about Wiscasset. There is a little ice pond near the village, whose

borders are

studded with blossoms, at intervals, producing most artistic effects.

Then the

drive to Dresden, returning through Alna, supplied us with delightful

scenes. We have

discussed

already the villages of Camden and Castine, and the attractions of Bar

Harbor. Belfast is a

little

city whose country roads, though not all very smooth, are dotted by

cottages

and skirted by farms and decorated with lakes and streams so as to hold

our

attention. Eastport and

Calais

should be sufficient with their waters and their inland drives to the

lakes and

streams behind them, to hold attention for a long time. Princeton and

its

lakes, among the largest in Maine, when all attendant smaller lakes are

taken

together, is the center of a very important and fascinating district. Aroostook County, in Houlton, Presque Isle, Fort Fairfield, Caribou and Fort Kent, has villages which are headquarters for a study of a fertile and magnificent farming district. Here, in a rich soil and in a strong way, the people of Aroostook carve their fortunes from their broad lands. In Schoodic Lake, and Grand Lake, at the southeast corner of the county, and in the very extensive Eagle Lakes at the northern end of the county, canoeing at its highest estate calls to the water lover. In fact, the Eagle Lakes offer perhaps a longer unbroken water route than any other lake route in the state. All this district is yet capable of very much larger development. It holds virgin forests and farm lands, so extensive, and watered by so many fine streams, that this county alone is worth, and perhaps ought eventually to receive, a special volume. Possibly if we unite Aroostook with northern Penobscot and the whole of Piscataquis, and the greater part of Somerset counties, we should have a district unrivaled in the world for its lake attractions. The villages from which one could set out are somewhat remote from one's destination. But these villages are largely experienced in supplying the needs of the traveler. They are not yet beautiful in themselves, not having had yet the age and necessary development to secure mellowness. They should be thought of more as points of departure, just as western villages are regarded.

APPLE AND DANDELION FLUFF - NORTH EDGECOMB  A MAINE CORNER - LINCOLNVILLE  LEANING TO THE SHORE - CAMDEN  JEFFERSON BORDERS  FAIR BANKS - LISBON  HIDDEN GABLES  KENNEBEC BLOSSOMS - WHITEFIELD  WHERE THE LAKE SHOALS - WISCASSET  PITCHER POND - NEAR BELFAST  A BURDEN OF BEAUTY - ALNA  THE CAMPUS OF BOWDOIN  A RETIRING COTTAGE  MARANACOOK  CAMDEN MOUNTAINS  NINE SISTERS - TOPSHAM  MAINE IN SPRING - OXFORD COUNTY |