CHAPTER III

BUT if that was the Day of

Wonder the one that followed was certainly the Day of Despair. It

started out

well enough. Jimmy was aroused early in the morning, when the dawn's

chill was

still in the air, so that for a few moments he was very

miserable, but the hot

tea and food, combined with a good fire, soon put him in spirits. He

and

Taw-kwo visited the steel traps and took from them three fine muskrats.

Then

they unfastened one end of the net and hauled it in. This was most

exciting.

First appeared a gleam of something white under the water; then the

gleam

slowly defined itself. A breathless moment followed. How big was the

fish? What

kind was it? And then with a flop it was on the bank, beating the

ground to the

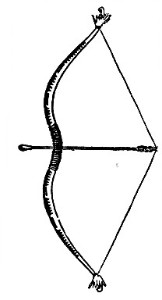

whoops of two enthusiastic boys. Taw-kwo had even produced a short

heavy bow

and some blunt-headed arrows, when a summons called them to

resume the

journey . .

About ten o'clock a few

drops of rain fell. Jimmy thought, of course, the band would seek

shelter. It

did not. The rain grew heavier, picking the surface of the river. Water

ran

down Jimmy's hair, speedily wetting him to the skin. He shivered and

looked

about with uneasiness on the landscape, rapidly growing

sodden. The Indians

seemed to mind the downpour no more than did the dogs. But Jimmy

suddenly felt

very lonely. The romance of the Magic Forest had quite departed, and he

began

to think of his warm home and his mother and father, and to wonder

whether

he

would ever see them again.

After a

little he began to cry softly to himself, the tears mingling with the

raindrops

running down his cheeks. But he was very still about it, for Taw-kwo

was in a

canoe near him, and little May-may-gwan was paddling solemnly in the

bow of

another just behind. The raindrops were coursing down her cheeks, too.

All that day Jimmy's heart

grew heavier and heavier. He paddled desperately in order to keep warm

and so

toward night grew tired also. It was a very blue day. In the evening he

stood

by the fire with the Indians and steamed. To his surprise the

night was not so

bad. The roofs of the shelters had been so slanted that the heat was

reflected

from them down upon the ground, which speedily dried. It was a little

damp, but

not all uncomfortable.

And next morning the sun was

shining brightly with true spring warmth. Thus Jimmy passed with credit

through

his trial by water. Rain and cold weather were always

disagreeable to him, but

in time he learned that one forgot all about it once it was finished.

Only twice that day was the

regular progress down river interrupted by anything exciting.

Long stretches

of still water were broken by swift little rapids, where Jimmy had to

sit very

still, and carries through the woods, where he had to work with the

others. He

was interested all the time. The most trivial incident was an

adventure. But a

little after noon, in shooting a particularly crooked and turbulent

rapid, in

spite of the best efforts of Makwa and Ah-kik, the canoe scraped

sharply

against a pointed stone. Instantly the water began to rush in

through a jagged

hole. By good fortune this was at the foot of the rapid. The Indians

paddled

desperately across the pool and grounded just in time. The goods were

hastily

thrown out and the canoe drawn up on the beach.

Jimmy looked sadly at the

rent in the bottom of the canoe. It was too bad. He supposed that now

the day's

journey would have to be given up.

But Makwa disappeared in the

woods while Ah-kik built a little fire. The other Indians continued on

down-stream. In a moment Makwa returned with a quantity of spruce pitch

on a

bit of bark. This he cooked over the fire with a little grease. Then

with a

stick of wood he smeared the melted gum about the hole, laid over it

smoothly a

bit of sacking, smeared more gum completely to cover the whole affair,

and

seared it close with a brand from the fire. In ten minutes the canoe

was as

good as ever.

About an hour later Makwa

whispered "Moos-wa, moos-wa." Jimmy had learned by now that when

Makwa whispered, something interesting was afoot,

so he looked

with all his

eyes. There, not two hundred yards away, knee deep in the water, stood

a cow

moose and her calf. The great animals, so awkward in

captivity but so

magnificent in their proper surroundings, stared uncertainly

at the gliding

canoes. The

wind was the wrong way for

the scent, and

a moose is not easily

alarmed by mere sight. In a moment they waded rapidly ashore and

disappeared

with a long swinging trot, but not before Jimmy had seen well the Roman

nose,

the big eyes, the massive shoulders of the animals. As moose to him had

always

seemed as remote as goblins, this new phase of the Magic Forest filled

him with

ecstatic rapture. And he was impressed still further by the lesson of

woods

moderation, for his companions had made no effort to kill the beautiful

creatures. For the present there was meat enough. something interesting was afoot,

so he looked

with all his

eyes. There, not two hundred yards away, knee deep in the water, stood

a cow

moose and her calf. The great animals, so awkward in

captivity but so

magnificent in their proper surroundings, stared uncertainly

at the gliding

canoes. The

wind was the wrong way for

the scent, and

a moose is not easily

alarmed by mere sight. In a moment they waded rapidly ashore and

disappeared

with a long swinging trot, but not before Jimmy had seen well the Roman

nose,

the big eyes, the massive shoulders of the animals. As moose to him had

always

seemed as remote as goblins, this new phase of the Magic Forest filled

him with

ecstatic rapture. And he was impressed still further by the lesson of

woods

moderation, for his companions had made no effort to kill the beautiful

creatures. For the present there was meat enough.

That evening after supper

Jimmy made friends. He was not so sleepy as the first evening

nor so

uncomfortable as the second, so he wandered here and

there trying his

new Indian

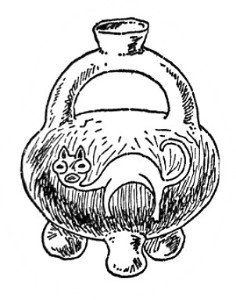

words. Especially did the cradles for the Indian babies interest him.

Everywhere he was smiled upon by the kindly people. Some even made him

little

presents of ornaments. Taw-kwo's father gave him a sheath-knife on a

belt. He

became acquainted with the other children and joined in their games,

sitting gravely cross-legged in a

circle, taking his turn at the knuckle bones with the rest.

Even in the three

days he had acquired a fair vocabulary, and

he understood

vaguely much more than he could

remember.

The next morning a lad of

sixteen led him hunting in the woods.

Jimmy was awkward but tried

hard, and after a number of futile stalks

the two succeeded in getting within sight of one of the drumming

partridges.

The bird was strutting up and down a smooth log, puffed out like a

turkey-cock,

and beating his wings rapidly to produce the hollow wooden drumming

Jimmy had

been hearing for three days. The Indian lad drew the blunt head of his

arrow to

the bow. Rap!

it struck a tree just beyond the partridge's head. The

bird flew away.

But now for the first time

Jimmy felt the joy of the chase. Here was something to work for. He

borrowed

the bow and the blunt arrows, and at every pause rap-rap-rapped

the

trees with his practice shots. By dint of imitation he succeeded after

a little

in acquiring a fair accuracy, though of course he could not beat his

Indian

friends. Then he set to work to stalk a partridge. Dozens and dozens he

frightened away by a clumsy approach. Four times his arrow went wide.

But then

at last the bird, alarmed by the twang of the bow, raised its head

directly

into the flying arrow. Jimmy cast his weapon from him, and fell upon

the game

with shrieks of delight.

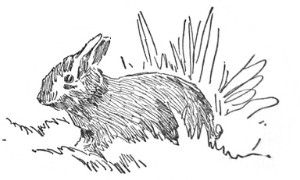

Asádi, the older

lad, taught

him how to spread a horse-hair loop across a rabbit trail, bending down

a

sapling in such a manner that it would spring straight when disturbed,

thus

jerking the rabbit into the air. At the foot of some of the waterfalls

great

fishing was to be had with the hook and line. A morsel of

meat, a

bright-colored feather, even a metal button so attached as to whirl was

bait

enough. There was no waiting. The instant the hook touched the water a

dozen

swirling fish were after it. Through the long evenings the big fellows

could be

seen jumping, shooting straight out into the air to fall back with a

heavy

splash. Once Jimmy hooked one of these, and had not Asádi

been at hand to help

him, he would have been pulled overboard. And when at last they

succeeded in

sliding the monster on to a flat rock, how beautiful he was with his

iridescent

eyes and the bright spots of his body. hand to help

him, he would have been pulled overboard. And when at last they

succeeded in

sliding the monster on to a flat rock, how beautiful he was with his

iridescent

eyes and the bright spots of his body.

Not the least interesting of

the many wood's puzzles were the numerous footprints to be

seen on the wet

sand of the beach. Asádi or Taw-kwo or even little Oginik,

who was much younger

than any of them, could tell him their names, but only long experience

taught

him what the animals might be like. "Makwa" they described broad

heavy prints. "Me-én-gan" said they when shown others

smaller and

rounder and not so flat. "Bisíw," they replied when he asked

about

certain padlike signs. But he did not know from that.

However, one day as the

canoes were paddling down a long narrow lake, Ah-kik called his

attention to

something white a long distance down the shore. The speck of white was

moving

slowly toward them. In a little while it defined itself as an animal.

Everybody

sat quite still. The beast was not in a hurry. Sometimes it trotted,

sometimes

it walked, sometimes it stopped to investigate something on the shore.

In the

canoes the dogs' backs were all bristling. Soon Jimmy could see that

the animal

was not white but gray, and that it looked a great deal like the Indian

dogs

except that it was larger and that it sloped from heavy shoulders to

lighter

haunches. When just opposite the waiting line of canoes, the

Indians raised a

mighty yell. Startled, the animal scuddled along the beach like the

wind. Point

after point it passed, still running, until at last, again as

a white speck,

it bobbed out of sight. The Indians laughed consumedly . .

"Me-én-gan,"

explained Ah-kik.

But Jimmy knew also the

English name now, for he had often watched the wolves in Bronx Park

cages.

Makwa he learned in a

manner

still more exciting. He and Taw-kwo came on a little open space in the

woods

one morning. The grass was almost knee high. Suddenly out of it, not

ten feet

away, a great black bear rose to his hind legs and said woof! Now if a

human being

in a civilized room says woof to you suddenly,

you are startled; but when

it is a big animal in a wild place, you beat all records on

the back jump. At

least, that is what Jimmy did, and he started to run away, but Taw-kwo

jumped

up and down and waved his arms frantically and shouted, until the bear,

who was

a peaceful beast, dropped to his four feet and ambled away. "Makwa,"

said Taw-kwo, when he had got his breath.

But the third was the most

exciting of all. That particular afternoon the Indians had gone into

camp

early, and now the whole band, with the exception of Jimmy and the very

youngest children, were off in the woods. Jimmy was trying to make

himself an

arrow, and was absorbed in the work. Suddenly he heard a strange

squeaking

noise near at hand, and looked up to discover two large gray kittens

tumbling

about not three feet away. And then, compelled by some strange

hypnotic

influence, his glance raised until it rested with a start of alarm on

the pine

shadow at the edge of the woods. A pair of fierce yellow eyes looked

into his

own. Little by little, he made

out a lithe form, pad-like paws, wide whiskers, tasselled

ears. And all at

once he realized that the beast was angry.

At that moment one of the

smaller children discovered the kittens, and

immediately toddled forward to

investigate such new playmates. A low, rumbling growl broke from the

shadow.

Like a streak of light the animal sprang. The mere weight of its body

knocked

the child from its feet. All the others cried out. The beast

hesitated, one

paw on the pappoose's chest, undecided what to do . .

Jimmy was frightened, but he

remembered seeing Makwa's gun standing against a log behind

him. At his first

movement the animal growled again and opened and shut its claws

restlessly.

Jimmy moved as cautiously as he could. The little Indian lay quite

still.

Finally, the long trade gun was in the white boy's hands. He had to

rest the

but on the ground and use both hands to cock it, and even then it was

so heavy

that he could just lift it to his eyes. The first movement of the

muzzle caused

the beast to utter a perfect thunder-storm of snarls. Jimmy knew that

he had

but a moment. He pointed the wavering barrel as well as he

could, and pulled

the trigger. That was all he knew about it. His next sensation was of

water in

the face, followed by an increasing ache in the region of his shoulder.

The

trade gun, unskilfully held, had kicked him about ten feet.

But there was the baby,

sound and well; and there was the animal, minus half its head; and

there were

the kittens, unfortunately killed by the returning dogs; and

there was Jimmy

with a brand new bit of information, -- that bisíw,1

with the broad,

padlike prints, was a huge cat.

And

so the days went by. Sometimes they floated all

day; sometimes they struggled through woods; sometimes they toiled

painfully

through swamps. They endured rain, wind, cold. Always the spring

advanced and

the freshet waters receded. Young ducks began to be seen. The trees of

the

forest grew smaller.

Caribou took the place of

deer. Jimmy could talk with his friends now, and, by dint of much

listening

could understand most of what was said.

At last, after coursing for

many miles down a broad swift stream without rapids, they came to where

another

river joined theirs, and on the point formed by the junction

they went ashore

and established a permanent camp. First the women pitched the

conical teepees

with the many poles. Then they built fire-holes and hung

kettles. Then they

cut quantities of balsam for the floors and to scatter on the

thresholds. And

finally they began the construction of a long rectangular lodge of

poles and

branches and decorated skins.

In the meantime the men were

all off hunting, and the boys were conducting an industrious fishery.

The

spoils were sliced thin, and jerked, or smoked. Then they were laid on

scaffolds out of reach of the dogs. In a week the camp was bountifully

supplied.

And finally the packs were

undone and all the gorgeous beaded and ornamented finery brought out,

brushed

and aired, after which the entire band settled into what seemed to

Jimmy to be

an anxious waiting. He asked them about it, and they replied, but the

words

were of those he had not learned. He only knew that around the lower

bend a

sentinel always stood. And one morning early that sentinel fired a

shot.

Instantly the camp swarmed into view. The men, seizing their guns, ran

eagerly

to the point. Jimmy followed in breathless excitement.

__________________

Click the

book image to turn

to the next Chapter.

Click the

book image to turn

to the next Chapter. |