| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2005 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to The Magic Forest Content Page |

(HOME) |

CHAPTER I

WHEN

James Ferris was only

five years old, he slipped from his bed, pattered barefooted

through the

bedroom and down the hall, and was finally reclaimed by an

excited

mother just

as he was about to crawl through the window on to the sloping roof of

the

veranda. James was promptly spanked, although he disclaimed

all knowledge of

the episode. About a year later he left his sleeping-car berth, and was

only

restrained All by the porter from stepping off the moving train. At the

age of

seven he horrified his family by climbing down four stories of a hotel

fire-escape. The third coincidence set his mother's wits to work. After

a time

it became fully established that Jimmy Ferris was a somnambulist, or

sleep-walker.

Jimmy did not know this. It was considered best to keep him in ignorance of the fact. The recurrence of his night prowlings was rare, and after his condition became recognized, he was never awakened. In fact, until the age of nine, at which time this story opens, he had made but six such excursions. Aside from this

unfortunate

tendency, he had never been very strong.

His passion had always been for out-of-door life, and that would have been the very best thing for him; but his mother was too worried about him. She exercised a general supervisory authority over such things as rubbers, flannel bands, sponge cake, and oatmeal, which convinced Jimmy that mortal man would die if his feet got wet or if his diet were in the least irregular. It is natural for a boy to pattern his mental cast by that of his mother, and Jimmie's mother was very anxious. Indeed, about this time she imagined that Jimmie's lungs were weak, and so nothing would do but that they must all go to Monterey for the summer and Santa Barabara for the winter. As Jimmy's great but thwarted ambition had always been to see the "big woods," he was more than delighted. They set out by the Canadian

Pacific railroad early in May. Jimmy was at the car window all

of the daylight

hours, marvelling at the Canadian country, the stretches of forest, the

numerous lakes. North of Lake Superior he was surprised to see still a

great

deal of snow lying in the hollows, and in fact, late one afternoon, the

big,

white flakes began to zigzag slowly through the air. Jimmy was filled

with

wonder. A snow-storm in May!

All

the afternoon he

flattened his little nose against the window, his eye wide

with the mystery of

the forest. He could see into it just about ten feet, but who knew what

lay

beyond that? His restless mind conjured up the hollows, the

streams, the

springs, the wild beasts. Up in through that country lay the Long Trail

to the

fur regions. At Sudbury, late in the afternoon, he had glimpsed a voyageur

just from the wilds. The man had worn a fur cap with the tail hanging

down

behind! He had been wrapped in a long blanket coat bound with a red

sash, and

his feet were encased in beaded moccasins! Jimmy's mind went

galloping off on

the leagues of the Long Trail and after he had gone to bed he dreamed

of it. He

too travelled in the Silent Places. About five o'clock in the

morning the train paused an instant because the driving wheels could

not grip

the slippery rails on the grade. The engineer promptly turned on his

sand. Five

minutes later he had forgotten the circumstance. But in that pause something had happened. Jimmy Ferris, travelling the Trail in imagination, had wandered down the aisle of the car, had stepped from the platform at precisely the moment the engineer reached for his sand lever, and was now blundering aimlessly through the falling snow, over rolling bald hills, clad only in his slippers, a pair of trousers, and his nightgown, firmly convinced in his own mind that he was discovering the North Pole.  Two hours and a half

later, which

of course meant seventy or eighty miles farther on, Mrs.

Ferris discovered her

son's berth empty. Then there was trouble! Telegrams, questions,

conjectures,

flew. Section men scurried over every inch of the track on hand-cars,

thinking

to find Jimmy's mutilated body. He was evidently not on the train: it

seemed

impossible that he could have left it while moving without receiving

some

injury. Nobody remembered that labored moment when the engine had

coughed its

protest of the grade. No sign nor clew could be discovered. Mrs. Ferris

was

prostrated; Mr. Ferris stricken to the heart; everybody else was

supremely

puzzled. Jimmy had simply vanished into thin air.

In

the meantime Jimmy went

on discovering the North Pole, and the arctic weather became

more and more

severe. He was just on the point of plucking the pole to take home with

him,

from which happy event he was being prevented however by the

numbness

of his hands, when he awoke and

looked about him. He knew perfectly well he

was no longer dreaming, but for a moment he seriously doubted whether

he was

alive. His last moments of consciousness had felt the yielding of a

Pullman

berth, had heard the regular clinkety-clank of the car wheels,

had seen the

thin crack of light that swayed between his curtains. And here all at

once he

was out on a gray, bleak, boulder-strewn hillside, without a

sign of berth, or

car, or even track anywhere within sight. You must remember that he

knew

nothing whatever of his sleep-walking propensities. He could

not summon to his

bewildered brain even a wild solution of the affair. Before him stretched a

mistlike forest country, indistinct in the early light, about whose

skeleton

branches lingered a faint, wraithlike fog. And all about him was a

great

silence.

He was not frightened; the

whole thing was too unexplained for that, and, being unable to

account for

himself in any way, he was as yet unterrified by a feeling of

responsibility.

But he was very cold. His thin slippers, which he had instinctively

assumed

before setting out to discover the North Pole, were wet through by the

damp

snow; his bare shanks were goose-fleshed, and a thin, cotton nightgown

and a

pair of

knee breeches are not

precisely

an early May costume in the North. Having been taught that damp feet

meant

pneumonia and inadequate clothing consumption, Jimmy immediately gave

himself

up for lost. "I must get back," he said to himself. Get back where? He had never

seen this country before. That Pullman car might be on the other side

of the

world. For a moment he imagined he might be dead, but. then a

certain sturdy

little piety of his own came to his aid.

It was not that. But since the human mind must have

explanations or perish,

and since Jimmy was only nine years old and more conversant with Grimm

and

Andersen than with medical authorities, and since sorcery is

after all much

nearer to the hearts of most of us than such a stupendous metamorphosis

as

this, he shortly concluded that he was living a fairy tale and that

this must

be the Magic Forest. In that case he must go

somewhere. He struck out sturdily, his mind quite at rest from the

fears that

would have assailed it had he been lost in an ordinary and

comprehensible

manner.

Of

course he set out in the

wrong direction. Even had he known enough to follow a back

track, it would

have been impossible for him to have done so. The back track

was covered by

the light fall of snow. Travel was difficult enough and

uncomfortable enough

in any direction, but level places are easier than hills. Accordingly,

Jimmy

took his way down toward the wraith of vapor, and so,

shortly

after an hour's stumbling through a fringe of wood, found

himself on the banks of a brawling north country river. By

this time the sun

was well over the horizon, the clouds had scattered, and

Jimmy's blood was

circulating, so that, had he only known it, the danger of pneumonia or

a

harmful chill had passed. But Jimmy did not know it.

He only knew that the repeated contact with melting snow had turned his

feet

positively blue, that his thin, wet garments sent a spasm of cold

through his

body every time a new movement brought their smooth clamminess next his

skin in

a fresh place, that the wood's brush had scraped and torn his skin

cruelly.

Once something abrupt and strange had glided away like a streak of

brown from a

thicket before him, startling him into a cry, which returned from the

great

silence to strangle in his throat. Now he stared in helpless

bewilderment at

the swift stream, and wondered what new thing he must do. It

would not have

surprised him to have been whisked back at any moment to his berth in

the

Pullman car. Above the little stone beach on which he stood, the river

boiled

and tumbled and whirled down a slope strewn with big and little

boulders. The

water was broken into foam, slid in a smooth green apron, twisted in

savage

eddies. The pool before him was filled with white froth. And Jimmy was a

very lonesome little boy in a great,

strange place.

Suddenly

at the extremity of

the vista something sprang into view and came shooting down the hurried

waters.

It stopped abruptly, worked jerkingly sideways, to slant with

terrific impetus

across the smooth apron. Jimmy's bewildered vision made out a canoe, a

birch-bark canoe of bright yellow with up-curved bows, of the sort he

had seen

pictures of in his father's Parkman.

It contained two men. As the canoe

leaped nearer and nearer, the men came more plainly into view. Their

bold,

copper-colored faces were set in rigid lines of attention, their beady

black

eyes were fixed unwaveringly on the difficulties of the descent, their

sinewy

brown hands wielded long paddles whose blades were colored vermilion.

Both

wore their hair long

about the napes of their necks and over their ears, and bound it in

place by

bands about their foreheads. Even before the boy's quick faculties had

sensed

these things, the craft had reached a spot where the current divided

about a

great boulder to tumble over a sunken ledge in a cataract. The men

simultaneously rose to their knees and thrust at their paddles in one

superhuman effort. The canoe quivered, jumped sideways, shot forward

just to

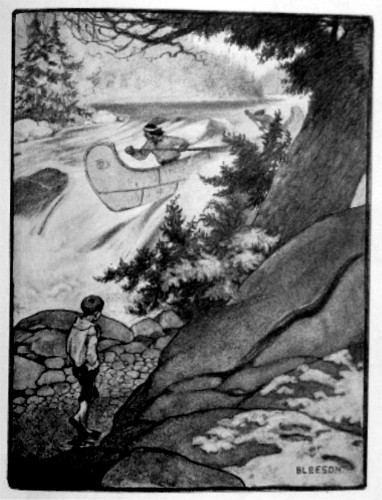

clear the boulder, and rushed on the cataract. "Ae! hi, hi, hi-yah!" shrieked the men in an ecstasy.  "The canoe quivered,... and rushed the cateract." The

craft leaped directly

out in the air. A smother of spray arose. It floated

peacefully in the eddy of

the pool.

Another canoe appeared,

another, then two, all rushing down the current, all taking

the leap. The air

was full of shoutings, of laughter. Some set to work at once

bailing water,

others looked eagerly up-stream to watch their successors shoot the

rapids.

Almost instantaneously, as it seemed, the empty place was alive. And

the little boy,

shivering in the shadow of the wood, shivered still more with mingled

terror

and delight; for now he saw that these were Indians, the wild Indians

of the

woods, of a hundred years ago, whose wigwams had given place to the New

York he

knew, about whom his father had read to him in Cooper, come back from

the mysterious,

romantic past to traverse the Magic Forest. He was frightened, and yet

he was

glad. They were Indians, and yet they looked kind. He did not know

whether to flee or whether to reveal

himself and ask for aid.

The trouble of a

decision

was saved him, however. The keen eyes of the savages did not long

overlook him.

Instantly he was surrounded by a curious group, eager to know the

meaning of

his appearance. The strange, handsome men in

moccasins talked to one another in beautiful singing

syllables; then an old

man knelt before him. "You get los'?" he

asked laboriously. Jimmy only stared. You see he really did not know

himself. "Where you liv'?" "New York,"

replied Jimmy. "New Yo'k," they

repeated to one another, puzzled. They thought they knew the place, for

far up

on the shores of the Hudson Bay is a fur-trading post called York Factory.

But how did this

child come to be here? "You go dere now?"

inquired the old Indian after a moment. He spoke swiftly to his

companions. "You wan' go to

York?" he asked. "Yes! Yes!" cried

Jimmy. "A' right,"

replied the Indian. "Is it far?" asked

Jimmy.

"Ver'

far." In the

meantime a little fire had been built, over which already a

tin pail was

bubbling. After a moment the Indian gave Jimmy a tin cup. "Drink him," said

he. It was tea, coal-black,

red-hot, without sugar and cream. Jimmy had never been allowed to drink

tea at

home, but he gulped this down, almost scalding his throat in the

process, and

at once felt better. While thus engaged, other Indians came through the

woods,

bearing heavy packs by means of straps passed across their foreheads.

Other

canoes, managed no less skilfully by women, shot the rapids. Children,

half-grown youths, girls, dogs, joined the group. A soft lisp of

excited

conversation arose. Old Makwa, the Indian who had interrogated Jimmy,

told them what he had learned. It was

surmised that the boy had become possessed by homesickness and

had

started for York Factory on

foot, ignorant

of the length of the journey; or perhaps that he had been lost

from a party

already well on its way toward that distant post. The band had

just been in to

trade its furs at Chapleau. It could not return south. Makwa cut the discussion

short. There was occasion for haste. He unceremoniously bundled thinly

clad

little Jimmy in a robe and deposited him gently in the waist of his

canoe. The

boy was well with them. Later, perhaps, when they returned to Chapleau

in the

fall.

He thrust the canoe strongly

into the current. It shot away. Ah-kik, the bowsman, headed it

down-stream.

The paddles dipped. And

now indeed, although he

did not for a moment suspect the fact, little Jimmy Ferris was setting

out on

the Long Trail.

|