| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Japanese Homes and their Surroundings Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER VII.

MISCELLANEOUS MATTERS. WELLS

AND WATER-SUPPLY. — FLOWERS. — INTERIOR ADORNMENTS. —

PRECAUTIONS AGAINST FIRE. — HOUSES OF FOREIGN STYLE. — ABSENCE OF

MONUMENTS.

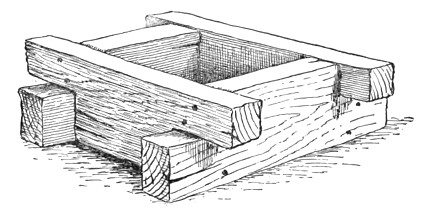

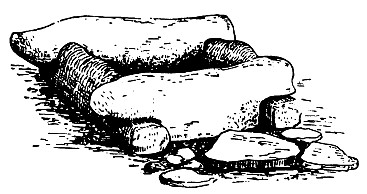

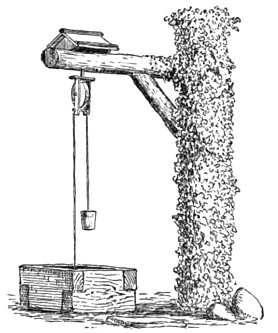

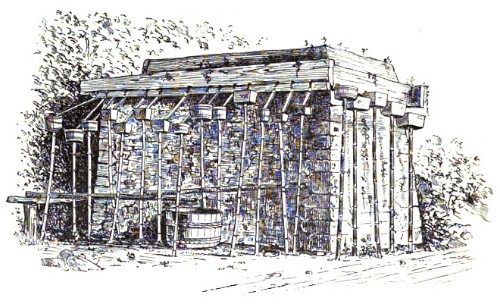

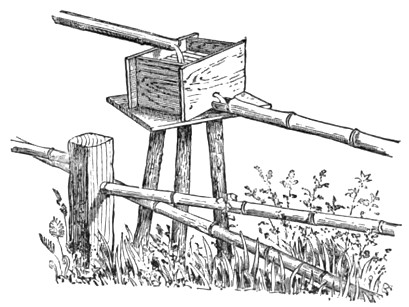

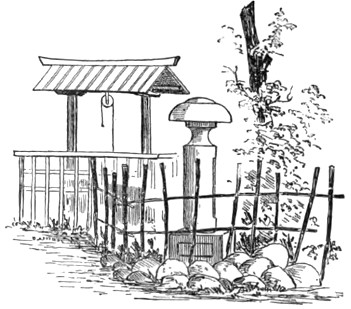

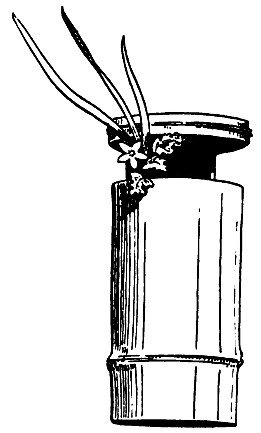

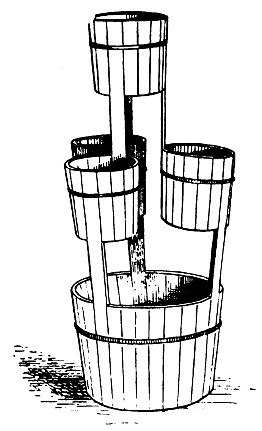

WITH the exception of a few of the larger cities, the water-supply of Japan is by means of wooden wells sunk in the ground. In Tokio, besides the ordinary forms of wells which are found in every portion of the city, there is a system of aqueducts conveying water from the Tamagawa a distance of twenty-four miles, and from Kanda a distance of ten miles or more. It is hardly within the province of this work to call attention to the exceeding impurity of much of the well-water in Tokio and elsewhere in Japan, as shown by many analyses, or to the imperfect way in which water is conveyed from remote places to Tokio and Yokohama. For valuable and interesting papers on this subject the reader is referred to the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Japan.1 The aqueducts in the city are made of wood, either in the shape of heavy square plank tubes or circular wooden pipes. These various conductors are intersected by open wells, in which the water finds its natural level, only partially filling them. These wells are to be found in the main streets as well as in certain open areas; and to them the people come, not only to get their water, but often to do light washing. The time must soon come when the authorities of Tokio will find it absolutely necessary to establish water-works for the supply of the city. Such a change from the present system would require an enormous expenditure at the outset, but in the end the community will be greatly benefited, not only in having more efficient means to quell the awful conflagrations which so frequently devastate their thoroughfares, but also in having a more healthful water-supply for family use. In their present imperfect method of water-service it is impossible to keep the supply free from local contamination; and though the death-rate of the city is low compared with that of many European and American cities, it would certainly be still further reduced by pure water made available to all.  287. ANCIENT FORM OF WELL-CURB In many country villages, where the natural conditions exist, a mountain brook is conducted by a rock-bound canal through the centre of the village street; and thus the water for culinary and other purposes is brought directly to the door of every house on that street. The wells are made in the shape of barrels of stout staves five or six feet in height. These taper slightly at their lower ends, and are fitted one within another; and as the well is dug deeper the sections are adjusted and driven down. Wells of great depth are often sunk in this way. The well made in this manner has the appearance, as it projects above the ground, of an ordinary barrel or hogshead partially buried. Stone curbs of a circular form are often seen. An ancient form of well-curb is a square frame, made of thick timber in the shape shown in fig. 287. The Chinese character for "well" is in the shape of this frame; and as one rides through the city or village he will often notice this character painted on the side of a house or over a door-way, indicating that in the rear, or within the house, a well is to be found. A picturesque well-curb of stone, made after this form, is shown in fig. 288, from a private garden in Tokio.  288. STONE WELL-CURB IN PRIVATE GARDEN IN TOKIO While the water is usually brought up by means of a bucket attached to the end of a long bamboo, there are various forms of frames erected over the well to support a pulley, in which runs a rope with a bucket attached to each end. Fig. 289 is an illustration of one of these frames. Sometimes the trunk of a tree is made to do service, as shown in fig. 290. In this case the old trunk was densely covered with a rich growth of Japanese ivy.   289. WOODEN WELL-FRAME 290. RUSTIC WELL-FRAME In the country kitchen the well is often within the house, as shown in the sketch fig. 167 (page 186). In the country, as well as in the city, the regular New England well-sweep is now and then seen. In the southern part of Japan particularly the well-sweep is very common; one is shown in the picture of a southern house (fig. 54, page 73). There are many ways of conveying water to villages by bamboo pipes. In Kioto many places are supplied by water brought in this way from the mountain brooks back of the city. At Miyajima, on the Inland Sea, water is brought, by means of bamboo pipes, from a mountain stream at the western end of the village. The water is first conveyed to a single shallow tank, supported on a rough pedestal of rock. The tank is perforated at intervals along its sides and on its end, and by means of bamboo gutters the water is conveyed to bamboo tubes standing vertically, — each bamboo having at its top a box or bucket, in which is a grating of bamboo to screen the water from the leaves and twigs. These bamboo tubes are connected with a system of bamboo tubes under-ground, and these lead to the houses in the village street below. Fig. 291 is an illustration of this structure. It was an old and leaky affair, but formed a picturesque mass beside the mountain road, covered as it was by a rich growth of ferns and mosses, and brightened by the water dripping from all points.  291. AQUEDUCT RESERVOIR AT MIYAJIMA, AKI Just beyond this curious reservoir I saw a group of small aqueducts, evidently for the supply of single houses. Fig. 292 illustrates one of a number of these seen along the road. Fig. 293 represents one of the old wells still seen in the Kaga yashiki, in Tokio, — an inclosure of large extent formerly occupied by the Daimio of Kaga, but now overgrown with bamboo grass and tangled bushes, while here and there evidences of its former beauty are seen in neglected groves of trees and in picturesque ponds choked with plant growth. The buildings of the Tokio Medical College and Hospital occupy one portion of the ground; and the new brick building of the Tokio University, a few dwellings for its foreign teachers, and a small observatory form another group. Scattered over this large inclosure are a number of treacherous holes guarded only by fences painted black. These are the remains of wells; and by their number one gets a faint idea of the dense community that filled this area in the days of the Shogunate. During the Revolution the houses were burned, and with them the wooden curbs of the wells, and for many years these deep holes formed dreadful pitfalls in the long grass.  292. AQUEDUCTS AT MIYAJIMA, AKI The effect of rusticity which the Japanese so much admire, and which they show in their gateways, fences, and other surroundings, is charmingly carried out in the wells; and the presence of a well in a garden is looked upon as adding greatly to its beauty. Hence, one sees quaint and picturesque curbs, either of stone and green with plant growth, or of wood and fairly dropping to pieces with decay. One sees literally a moss-covered bucket and well, too; but, alas! the water is not the cold, pure fluid which a New Englander is accustomed to draw from similar places at home, but often a water far from wholesome, and which to make so is generally boiled before drinking. We refer now to the city wells; and yet the country wells are quite as liable to contamination.  293. WELL IN KAGA YASHIKI, TOKIO Having described in the previous pages the permanent features of the house and its surroundings, a few pages may be properly added concerning those objects which are hung upon the walls as adornments. A few objects of household use have been mentioned, such as pillows, hibachi, tabako-bon, lamps, candlesticks, and towel-racks, as naturally associated with the mats, kitchen, bathing conveniences, etc. Any further consideration of these movable objects would lead us into a discussion of the bureaus, chests, baskets, trays, dishes, and the whole range of domestic articles of use, and might, indeed, furnish material enough for another volume. A few pages, however, must be added on the adornments of the room, and the principles which govern the Japanese in these matters. As flowers form the most universal decoration of the rooms from the highest to the lowest classes, these will be first considered. The love of flowers is a national trait of the Japanese. It would be safe to say that in no other part of the world is the love of flowers so universally shown as in Japan. For pictorial illustration flowers form one of the most common themes; and for decorative art in all its branches flowers, in natural or conventional shapes, are selected as the leading motive. In their light fabrics, — embroidery, pottery, lacquers, wall-papers, fans, — and even in their metal work and bronzes, these charming and perishable objects are constantly depicted and wrought. In their social life, also, these things are always present. From birth to death, flowers are in some way associated with the daily life of the Japanese; and for many years after their death their graves continue to receive fresh floral tributes. A room in the very humblest of houses will have in its place of honor — the tokonoma — a flower-vase, or a section of bamboo hanging from its side, or some form of receptacle suspended from the open portion of the room above, or in front of some ornamental opening in which flowers are displayed. On the street one often meets the flower vendor; and at night, flower fairs are one of the most common attractions. The arrangement of flowers forms a part of the polite education of the Japanese, and special rules and methods for their appropriate display have their schools and teachers. Within the house there are special places where it is proper to display flowers. In the tokonoma, as we have said, is generally a vase of bronze or pottery in which flowers are placed, — not the heterogeneous mass of color comprised in a jumble of flowers, as is too often the case with us; but a few flowers of one kind, or a big branch of cherry or plum blossoms are quite enough to satisfy the refined tastes of these people. Here, as in other matters, the Japanese show their sense of propriety and infinite refinement. They most thoroughly abominate our slovenly methods, whereby a clump of flowers of heterogeneous colors are packed and jammed together, with no room for green leaves: this we call a bouquet; and very properly, since it resembles a ball, — a variegated worsted ball. These people believe in the healthy contrast of rough brown stem and green leaves, to show off by texture and color the matchless life-tones of the delicate petals. We, however, in our stupidity are too often accustomed to tear off the flowers that Nature has so deftly arranged on their own wood stems, and then with thread and bristling wire to fabricate a feeble resemblance to the milliner's honest counterfeit of cloth and paper; and by such treatment, at the end of a few hours, we have a mass equally lifeless. In their flower-vases, too, they show the most perfect knowledge of contrasts. To any one of taste it is unnecessary to show how inappropriate our gilt and often brilliantly colored flower-vases are for the objects they are to hold. By employing such receptacles, all effects of color and pleasing contrasts are effectually ruined. The Japanese flower-vase is often made of the roughest and coarsest pottery, with rough patches of glaze and irregular contour; it is made solid and heavy, with a good bottom, and is capable of holding a big cherry branch without up-setting. Its very roughness shows off by contrast the delicate flowers it holds. With just such rough material as we use in the making of drain-tiles and molasses jugs, the Japanese make the most fascinating and appropriate flower-vases; but their potters are artists, and, alas! ours are not. In this connection it is interesting to note that in our country, artists, and others having artistic tastes, have always recognized the importance of observing proper contrasts between flowers and their holders, and until within a very few years have been forced, for want of better receptacles, to arrange flowers in German pottery-mugs, Chinese ginger-jars, and the like. Though these vessels were certainly inappropriate enough, the flowers looked vastly prettier in them than they ever could in the frightful wares designed expressly to hold them, made by American and European manufacturers. What a satire on our art industries, — a despairing resort to beer-mugs, ginger-jars and blacking-pots, for suitable flower-vases! Who does not recall, indeed cannot see to-day on the shelves of most "crockery shops," a hideous battalion of garish porcelain and iniquitous parian vases, besides other multitudinous evidences of utter ignorance as to what a flower-vase should be, in the discordantly colored and decorated glass receptacles designed to hold these daintiest bits of Nature's handiwork? Besides the flower-vase made to stand on the floor, the Japanese have others which are made to hang from a hook, — generally from the post or partition that divides the tokonoma from its companion recess, or sometimes from a corner-post. When a permanent partition occurs in a room, it is quite proper to hang the vase from the middle post. In all these cases it is hung midway between the floor and the ceiling. These hanging flower vases are infinite in form and design, and are made of pottery, bronze, bamboo, or wood. Those made of pottery and bronze may be in the form of simple tubes; often, however, natural forms are represented, — such as fishes, insects, sections of bamboo, and the like.  294. HANGING FLOWER-HOLDER OF BAMBOO The Japanese are fond of ancient objects, and jars which have been dug up are often mutilated, at least for the antiquarian, by having rings inserted in their sides so that they may be hung up for flower-holders. A curious form of holder is made out of a rugged knot of wood. Any quaint and abnormal growth of wood, in which an opening can be made big enough to accommodate a section of bamboo to hold the water, is used for a flower-vase. Such an object will be decorated with tiny bronze ants, a silver spider's web with bronze spider, and pearl wrought in the shape of a fungus. These and other singular caprices are worked into and upon the wood as ornaments. A very favorite form of flower-holder is one made of bamboo. The bamboo tube is worked in a variety of ways, by cutting out various sections from the sides. Fig. 294 represents an odd, yet common shape, arranged for cha-no-yu (tea-parties), and sketched at one of these parties. The bamboo is an admirable receptacle for water, and a section of it is used for this purpose in many forms of pottery and bronze flower-holders.  295. HANGING FLOWER-HOLDER OF BASKET-WORK Rich brown-colored baskets are also favorite receptacles for flowers, a segment of bamboo being used to hold the water. The accompanying figure (fig. 295) is a sketch of a hanging basket, the flowers having been arranged by a lover of the tea-ceremonies and old pottery. Many of these baskets are quite old, and are highly prized by the Japanese. At the street flower-fairs cheap and curious devices are often seen for holding flower-pots. The annexed figure (fig. 296) illustrates a form of bracket in which a thin irregular-shaped slab of wood has attached to it a crooked branch of a tree, upon the free ends of which wooden blocks are secured as shelves upon which the flower-pots are to rest. A hole is made at the top so that it may be hung against the wall, and little cleats are fastened crosswise to hold long strips of stiff paper, upon which it is customary to write stanzas of poetry. These objects are of the cheapest description, can be got for a few pennies, and are bought by the poorest classes. For flower-holders suspended from above, a common form is a square wooden bucket, or one made out of pottery or bronze in imitation of this form. Bamboo cut in horizontal forms is also used for suspended flower-holders. Indeed, there seems to be no end of curious objects used for this purpose, — a gourd, the semi-cylindrical tile, sea-shells, as with us, and forms made in pottery or bronze in imitation of these objects.  296. CHEAP BRACKET FOR FLOWER-POTS Quaint and odd-shaped flower-stands are made in the form of buckets. The following figure (fig. 297) represents one sketched at the National Exposition at Tokio in 1877. Its construction was very ingenious; three staves of the lower bucket were continued upward to form portions of three smaller buckets above, and each of these, in turn, contributed a stave to the single bucket that crowned the whole. Another form, made by the same contributor though not so symmetrical, was quite as odd.  297. CURIOUS COMBINATION OF BUCKETS FOR FLOWERS Curious little braided-straw affairs are made to hold flowers, or rather the bamboo segments in which the flowers are kept. These are made in the form of insects, fishes, mushrooms, and other natural objects. These are mentioned, not that they have a special merit, but to illustrate the devices used by the common people in decorating their homes. Racks of wood richly lacquered are also used, from which hanging flower-holders are suspended. These objects are rarely seen now, and I have never chanced to see one in use. In the chapter on Interiors various forms of vases are shown in the tokonoma.

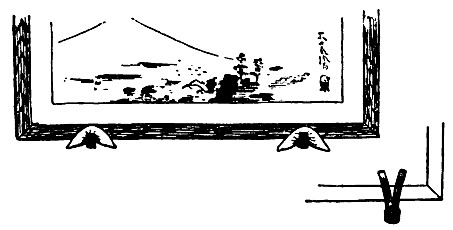

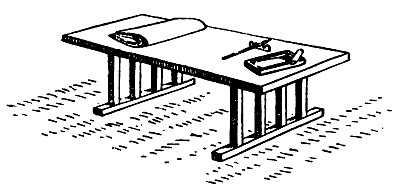

My interest in Japanese homes was first aroused by wishing to know precisely what use the Japanese made of a class of objects with which I had been familiar in the Art Museums and private collections at home; furthermore, a study of their houses led me to search for those evidences of household decoration which might possibly parallel the hanging baskets, corner brackets, and especially ornaments made of birch bark, fungi, moss, shell-work, and the like, with which our humbler homes are often garnished. It was delightful to find that the Japanese were susceptible to the charms embodied in these bits of Nature, and that they too used them in similar decorative ways. At the outset, search for an object aside from the bare rooms seemed fruitless enough. At first sight these rooms appeared absolutely barren; in passing from one room to another one got the idea that the house was to be let. Picture to yourself a room with no fire-place and accompanying mantel, — that shelf of shelves for the support of pretty objects; no windows with their convenient interspaces for the suspension of pictures or brackets; no table, rarely even cabinets, to hold bright-colored bindings and curious bric-à-brac; no side-boards upon which to array the rich pottery or glistening porcelain; no chairs, desks, or bedsteads, and consequently no opportunity for the display of elaborate carvings or rich cloth coverings. Indeed, one might well wonder in what way this people displayed their pretty objects for household decorations. After studying the Japanese home for a while, however, one comes to realize that display as such is out of the question with them, and to recognize that a severe Quaker-like simplicity is really one of the great charms of a Japanese room. Absolute cleanliness and refinement, with very few objects in sight upon which the eye may rest contentedly, are the main features in household adornment which the Japanese strive after, and which they attain with a simplicity and effectiveness that we can never hope to reach. Our rooms seem to them like a curiosity shop, and "stuffy" to the last degree. Such a maze of vases, pictures, plaques, bronzes, with shelves, brackets, cabinets, and tables loaded down with bric-à-brac, is quite enough to drive a Japanese frantic. We parade in the most unreasoning manner every object of this nature in our possession; and with the periodical recurrence of birthday and Christmas holidays, and the consequent influx of new things, the less pretty ones already on parade are banished to the chambers above to make room for the new ones; and as these in turn get crowded out they rise to the garret, there to be providentially broken up by the children, or to be preserved for future antiquarians to contemplate, and to ponder over the condition of art in this age. Our walls are hung with large fish-plates which were intended to hold food; heavy bronzes, which in a Japanese room are made to rest solidly on the floor, and to hold great woody branches of the plum or cherry with their wealth of blossoms, are with us often placed on high shelves or perched in some perilous position over the door. The ignorant display is more rarely seen of thrusting a piece of statuary into the window, so that the neighbor across the way may see it; when a silhouette, cut out of stiff pasteboard, would in this position answer all the purposes so far as the inmates are concerned. How often we destroy an artist's best efforts by exposing his picture against some glaring fresco or distracting wall-paper! And still not content with the accumulated misery of such a room, we allow the upholsterer and furnisher to provide us with a gorgeously framed mirror, from which we may have flashed back at us the contents of the room reversed, or, more dreadful still, a reverberation of these horrors through opposite reflecting surfaces, — a futile effort of Nature to sicken us of the whole thing by endless repetition.2 That we in America are not exceptional in these matters of questionable furnishing, one may learn by listening to an English authority on this subject, — one who has done more than any other writer in calling attention not only to violations of true taste in household adornment, but who points out in a most rational way the correct paths to follow, not only to avoid that which is offensive and pretentious, but to arrive at better methods and truer principles in matters of taste. We refer to Charles L. Eastlake and his timely work entitled "Hints on Household Taste." In his animadversions on the commonplace taste shown in the furnishing of English houses, he says "it pervades and vitiates the judgment by which we are accustomed to select and approve the objects of every-day use which we see around us. It crosses our path in the Brussels carpet of our drawing-room; it is about our bed in the shape of gaudy chintz; it compels us to rest on chairs, and to sit at tables which are designed in accordance with the worst principles of construction, and invested with shapes confessedly unpicturesque. It sends us metal-work from Birmingham, which is as vulgar in form as it is flimsy in execution. It decorates the finest modern porcelain with the most objectionable character of ornament. It lines our walls ,with silly representations of vegetable life, or with a mass of uninteresting diaper. It bids us, in short, furnish our houses after the same fashion as we dress ourselves, — and that is with no more sense of real beauty than if art were a dead letter." Let us contrast our tastes in these matters with those of the Japanese, and perhaps profit by the lesson. In the previous chapters sufficient details have been given for one to grasp the structural features of a Japanese room. Let us now observe that the general tone and color of a Japanese apartment are subdued. Its atmosphere is restful; and only after one has sat on the mats for some time do the unostentatious fittings of the apartment attract one's notice. The papers of the fusuma of neutral tints; the plastered surfaces, when they occur equally tinted in similar tones, warm browns and stone-colors predominating; the cedar-board ceiling, with the rich color of that wood; the wood-work everywhere modestly conspicuous, and always presenting the natural colors undefiled by the painter's miseries, — these all combine to render the room quiet and refined to the last degree. The floor in bright contrast is covered with its cool straw matting, — a uniform bright surface set off by the rectangular black borders of the mats. It is such an infinite comfort to find throughout the length and breadth of that Empire the floors covered with the unobtrusive straw matting. Monotonous some would think: yes, it has the monotony of fresh air and of pure water. Such a room requires but little adornment in the shape of extraneous objects; indeed, there are but few places where such objects can be placed. But observe, that while in our rooms one is at liberty to cover his wall with pictures without the slightest regard to light or effect, the Japanese room has a recess clear and free from the floor to the hooded partition that spans it above, and this recess is placed at right angles to the source of light; furthermore, it is exalted as the place of highest honor in the room, — and here, and here alone, hangs the picture. Not a varnished affair, to see which one has to perambulate the apartment with head awry to get a vantage point of vision, but a picture which may be seen in its proper light from any point of the room. In the tokonoma there is usually but one picture exposed, — though, as we have seen, this recess may be wide enough to accommodate a set of two or three.  298. FRAMED PICTURE, WITH SUPPORTS Between the kamoi, or and the ceiling is a space say of eighteen inches or more, according to the height of the room; and here may sometimes be seen a long, narrow picture, framed in a narrow wood-border, or secured to a flat frame, which is concealed by the paper or brocade that borders the picture. This picture tips forward at a considerable angle, and is supported on two iron hooks. In order that the edge of the frame may not be scarred by the iron, it is customary to interpose triangular red-crape cushions. A bamboo support is often substituted for the iron hooks, as shown in the sketch (fig. 298). The picture may be a landscape, or a spray of flowers; but more often it consists of a few Chinese characters embodying some bit of poetry, moral precept, or sentiment, — and usually the characters have been written by some poet, scholar, or other distinguished man. The square wooden post which comes in the middle of a partition between two corners of the room may be adorned by a long, narrow, and thin strip of cedar the width of the post, upon which is painted a picture of some kind. This strip, instead of being of wood, may be of silk and brocade, like a kake-mono, having only one kaze-obi hanging in the middle from above. Cheap ones may be of straw, rush, or thin strips of bamboo. This object, of whatever material, is called hashira kakushi, — literally meaning "post-hide." If of wood, both sides are decorated; so that after one side has done duty for awhile the other side is exposed. The wood is usually of dark cedar evenly grained, and the sketch is painted directly on the wood. Fig. 299 shows both sides of one of these strips.  299. HASHIRA-KAKUSHI The decoration for these objects is very skilfully treated by the artist; and while it might bother our artists to know what subject to select for a picture on so awkward and limited a surface, it offers no trouble to the Japanese decorator. He simply takes a vertical slice out of some good subject, as one might get a glimpse of Nature through a slightly open door, — and imagination is left to supply the rest. These objects find their way to our markets, but the bright colors used in their decoration show that they have been painted for the masses in this country. The post upon which this kind of picture is hung, as well as the toko-bashira, may also be adorned with a hanging flower-holder such as has already been described. A Japanese may have a famous collection of pictures, yet , these are stowed away in his kura, with the exception of the one exposed in the tokonoma. If he is a man of taste, he changes the picture from time to time according to the season, the character of his guests, or for special occasions. In one house where I was a guest for a few days the picture was changed every day. A picture may do duty for a few weeks or months, when it is carefully rolled up, stowed away in its silk covering and box, and another one is unrolled. In this way a picture never becomes monotonous. The listless and indifferent way in which an American will often regard his own pictures when showing them to a friend, indicates that his pictures have been so long on his walls that they no longer arouse any attention or delight. It is true, one never wearies in contemplating the work of the great masters; but one should remember that all pictures are not masterpieces, and that by constant exposure the effect of a picture becomes seriously impaired. The way in which pictures with us are crowded on the walls, — many of them of necessity in the worst possible light, or no light at all when the windows are muffled with heavy curtains, — shows that the main interest centres in their embossed gilt frames, which are conspicuous in all lights. The principle of constant exposure is certainly wrong; a good picture is all the more enjoyable if it is not forever staring one in the face. Who wants to contemplate a burning tropical sunset on a full stomach, or a drizzling northern mist on an empty one? And yet these are the experiences which we are often compelled to endure. Why not modify our rooms, and have a bay or recess, — an alcove in the best possible light, — in which one or two good pictures may be properly hung, with fitting accompaniments in the way of a few flowers, or a bit of pottery or bronze? We have never modified the interior arrangement of our house in the slightest degree from the time when it was shaped in the most economical way as a shelter in which to eat, sleep, and die, — a rectangular kennel, with necessary holes for light, and necessary holes to get in and out by. At the same time, its inmates were saturated with a religion so austere and sombre that the possession of a picture was for a long time looked upon as savoring of worldliness and vanity, unless, indeed, the subject suggested the other world by a vision of hexapodous angels, or of the transient resting-place to that world in the guise of a tombstone and willows, or an immediate departure thereto in the shape of a death-bed scene. Among the Japanese all collections of pottery and other bric-à-brac are, in the same way as the pictures, carefully enclosed in brocade bags and boxes, and stowed away to be unpacked only when appreciative friends come to the house; and then the host enjoys them with equal delight. Aside from the heightened enjoyment sure to be evoked by the Japanese method, one is spared an infinite amount of chagrin and misery in having an unsophisticated friend become enthusiastic over the wrong thing, or mistake a rare etching of Dante for a North American savage, or manifest a thrill of delight over an object because he learns incidentally that its value corresponds with his yearly grocery bill. Nothing is more striking in a Japanese room than the harmonies and contrasts between the colors of the various objects and the room itself. Between the picture and the brocades with which it is mounted, and the quiet and subdued color of the tokonoma in which it is hung, there is always the most refined harmony, and such a background for the delicious and healthy contrasts of color when a spray of bright cherry blossoms enlivens the quiet tones of this honored place! The general tone of the room sets off to perfection the simplest spray of flowers, a quiet picture, a rough bit of pottery or an old bronze; and at the same time a costly and magnificent piece of gold lacquer blazes out like a gem from these simple surroundings, — and yet the harmony is not disturbed. It is an interesting fact that the efforts at harmonious and decorative effects which have been made by famous artists and decorators in this country and in England have been strongly imbued by the Japanese spirit, and every success attained is a confirmation of the correctness of Japanese taste. Wall-papers are now more quiet and unobtrusive; the merit of simplicity and reserve where it belongs, and a fitness everywhere, are becoming more widely recognized. It is rare to see cabinets or conveniences for the display of bric-à-brac in a Japanese house, though sometimes a lacquer-stand with a few shelves may be seen, — and on this may be displayed a number of objects consisting of ancient pottery, some stone implements, a fossil, old coins, or a few water-worn fragments of rock brought from China, and mounted on dark wood stands. The Japanese are great collectors of autographs, coins, brocades, metal-work, and many other groups of objects; but these are rarely exposed. In regard to objects in the tokonoma, I have seen in different tokonoma, variously displayed, natural fragments of quartz, crystal spheres, curious waterworn stones, coral, old bronze, as well as the customary vase for flowers or the incense-burner. These various objects are usually, but not always, supported on a lacquer-stand. In the chigai-dana I have also noticed the sword-rack, lacquer writing-box, maki-mono, and books; and when I was guilty of the impertinence of peeking into the cupboards, I have seen there a few boxes containing pottery, pictures, and the like, — though, as before remarked, such things are usually kept in the kura. Besides the lacquer cabinets, there may be seen in the houses of the higher class an article of furniture consisting of a few deep shelves, with portions of the shelves closed, forming little cupboards. Such a cabinet is used to hold writing-paper, toilet articles, trays for flowers, and miscellaneous objects for use and ornament. These cases are often beautifully lacquered.  300. WRITING-DESK The usual form of writing-desk consists of a low stool not over a foot in height, with plain side-pieces or legs for support, sometimes having shallow drawers; and this is about the only piece of furniture that would parallel our table. The illustration (fig. 300) shows one of these tables, upon which may be seen the paper, ink-stone, brush, and brush-rest.

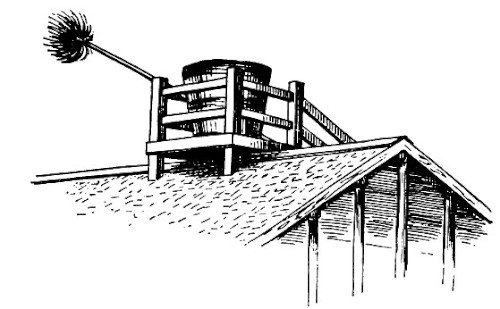

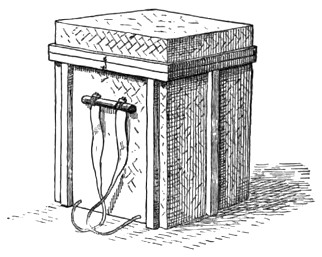

In the cities and large villages the people stand in constant fear of conflagrations. Almost every month they are reminded of the instability of the ground they rest upon by tremors and slight shocks, which may be the precursors of destructive earthquakes, usually accompanied by conflagrations infinitely more disastrous. Allusion has been made to the little portable engines with which houses are furnished. In the city house one may notice a little platform or staging with handrail erected on the ridge of the roof (fig. 301); a ladder or flight of steps leads to this staging, and on alarms of fire anxious faces may be seen peering from these lookouts in the direction of the burning buildings. It is usual to have resting on the platform a huge bucket or half barrel filled with water, and near by a long-handled brush; and this is used to sprinkle water on places threatened by the sparks and fire-brands, which often fill the air in times of great conflagrations.  301. STAGING ON HOUSE-ROOF, WITH BUCKET AND BRUSH During the prevalence of a high wind it is a common sight to see the small dealers packing their goods in large baskets and square cloths to tie up ready to transport in case of fire. At such times the windows and doors of the kura are closed and the chinks plastered with mud, which is always at hand either under a platform near the door or in a large earthen jar near the openings. In private dwellings, too, at times of possible danger, the more precious objects are packed up in a square basket-like box, having straps attached to it, so that it can easily be transported on one's shoulders (fig. 302).  302. BOX FOR TRANSPORTING ARTICLES In drawing to a close this description of Japanese homes and their surroundings, I have to regret that neither time, strength, nor opportunity enabled me to make it more complete by a description, accompanied by sketches, of the residences of the highest classes in Japan. Indeed, it is a question whether any of the old residences of the Daimios remain in the condition in which they were twenty years ago, or before the Revolution. Even where the buildings remain, as in the castles of Nagoya and Kumamoto, busy clerks and secretaries are seen sitting in chairs and writing at tables in foreign style; and though in some cases the beautifully decorated fusuma, with the elaborately carved ramma and rich wood-ceiling are still preserved, — as in the castle of Nagoya, as well as in many others doubtless, — the introduction of varnished furniture and gaudy-colored foreign carpets in some of the apartments has brought sad discord into the former harmonies of the place. In Tokio a number of former Daimios have built houses in foreign style, though these somehow or other usually lack the peculiar comforts of our homes. Why a Japanese should build a house in foreign style was somewhat of a puzzle to me, until I saw the character of their homes and the manner in which a foreigner in some cases was likely to behave on entering a Japanese house. If he did not walk into it with his boots on, he was sure to be seen stalking about in his stockinged feet, bumping his head at intervals against the kamoi, or burning holes in the mats in his clumsy attempts to pick up coals from the hibachi, with which to light his cigar. Not being able to sit on the mats properly, he sprawls about in attitudes confessedly as rude as if a Japanese in our apartments were to perch his legs on the table. If he will not take off his boots, he possibly finds his way to the garden, where he wanders about, indenting the paths with his boot-heels or leaving scars on the verandah, possibly washing his hands in the chōdzu-bachi, and generally making himself the cause of much discomfort to the inmates. It was a happy idea when those Japanese who from their prominence in the affairs of the country were compelled to entertain the "foreign barbarian," conceived the idea of erecting a cage in foreign fashion to hold temporarily the menagerie which they were often compelled to receive. Seriously, however, the inelastic character of most foreigners, and their inability to adapt themselves to their surroundings have rendered the erection of buildings in foreign style for their entertainment not only a convenience but an absolute necessity. It must be admitted that for the activities of business especially, the foreign style of office and shop is not only more convenient but unquestionably superior. The former Daimio of Chikuzen was one of the first, I believe, to build a house in foreign style in Tokio, and this building is a good typical example of an American two-story house. Attached, however, to this house is a wing containing a number of rooms in native style. Fig. 123 (page 142) shows one of these rooms. The former Daimio of Hizen also lives in a foreign house, and there are many houses in Tokio built by Japanese after foreign plans. In an earlier portion of this work an allusion was made to the absence of those architectural monuments which are so characteristic of European countries. The castles of the Daimios, which are lofty and imposing structures, have already been referred to. There are fortresses also of great extent and solidity, — notably the one at Osaka, erected by Hideyoshi on an eminence near the city; and though the wooden structures formerly surmounting the walls were destroyed by Iyeyasu in 1615, the stone battlements as they stand to-day must be considered as among the marvels of engineering skill, and the colossal masses of rock seem all the more colossal after one has become familiar with the tiny and perishable dwellings of the country. In the walls of this fortress are single blocks of stone — at great heights, too, above the surrounding level of the region — measuring in some cases from thirty to thirty-six feet in length, and at least fifteen feet in height. These huge blocks have been transported long distances from the mountains many miles away from the city. Attention is called to the existence of these remarkable monuments as an evidence that the Japanese are quite competent to erect such buildings, if the national taste had inclined them in that way. So far as I know, a national impulse has never led the Japanese to commemorate great deeds in the nation's life by enduring monuments of stone. The reason may be that the plucky little nation has always been successful in repelling invasion; and a peculiar quality in their temperament has prevented them from perpetuating in a public way, either by monuments or by the naming of streets and bridges, the memories of victories won by one section of the country over another. Rev. W. E. Griffis, in an interesting article on "The Streets and Street-names of Yedo,"3 in noticing the almost total absence of the names of great victories or historic battlefields in the naming of the streets and bridges in Tokio, says: "It would have been an unwise policy in the great unifier of Japan, Iyeyasu, to have given to the streets in the capital of a nation finally united in peaceful union any name that would be a constant source of humiliation, that would keep alive bitter memories, or that would irritate freshly-healed wounds. The anomalous absence of such names proves at once the sagacity of Iyeyasu, and is another witness to the oft-repeated policy used by the Japanese in treating their enemies, — that is, to conquer them by kindness and conciliation." ______________________ 1 Professor Atkinson, in the Journal of the Asiatic Society, vol. vi. part i.; Dr. Geerts, ibid., vol. vii. part iii. Dr. O. Korschelt has made an extremely valuable contribution to the Asiatic Society of Japan, on the water-supply of Tokio. Aided by Japanese students, he has made many analyses of well-waters and waters from the city supply, and shows that, contrary to the conclusions of Professor Atkinson, the high-ground wells are on the whole much purer than those on lower ground. Dr. Korschelt also calls attention to the great number of artesian wells sunk in Tokio. by means of bamboo tubes driven into the ground. The ordinary form of well is carried down thirty or forty feet in the usual way, and then at the bottom bamboo tubes are driven to great depths, ranging from one hundred to two hundred feet and more. He speaks of a number of these wells in Tokio and the suburbs as overflowing. There is one well not far from the Tokio Daigaku which overflows; and a very remarkable sight it is to see the water pouring over a high well-curb and flooding the ground in the vicinity. He shows that pure water may be reached in most parts of Tokio by means of artesian wells; and to this source the city must ultimately look for its water-supply. For further particulars concerning this subject, the reader is referred to Dr. Korschelt's valuable paper in the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, vol. part iii., p. 143. 2 The pier-glass is happily unknown in Japan; a small disk of polished metal represents the mirror. and is wisely kept in a box till needed! 3 Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, vol. i. p. 20. |