UP

ANCHOR

Yo-o

heave ho! an' a y-o heave ho!

And lift

her down the bay —

We're

off to the Pillars of Hercules,

All on a

summer's day.

We're

off wi' bales of our Southdown wool,

Our

fortune all to win,

And

we'll bring ye gold and gowns o' silk.

Veils

o' sendal as white as milk,

And

sugar and spice galore, lasses —

When our

ship comes in!

|

VII

THE

VENTURE OF NICHOLAS GAY

HOW

NICHOLAS GAY, THE MERCHANT'S SON, KEPT FAITH WITH A STRANGER AND

SERVED THE KING

NICHOLAS

GAY stood on the wharf by his father's warehouse, and the fresh

morning breeze that blew up from the Pool of the Thames was ruffling

his bright hair. He could hear the seamen chanting at the windlass,

and the shouts of the boatmen threading their skiffs and scows in and

out among the crowded shipping. There were high-pooped Flemish

freighters, built to hold all the cargo possible for a brief voyage;

English coasting ships, lighter and quicker in the chop of the

Channel waves; larger and more dignified London merchantmen, that had

the best oak of the Weald in their bones and the pick of the

Southdown wool to fill them full; Mediterranean galleys that shipped

five times the crew and five times the cargo of a London ship;

weather-beaten traders that had come over the North Sea with cargoes

of salt fish; and many others.

The

scene was never twice the same, and the boy never tired of it. Coming

into port with a cargo of spices and wine was a long Mediterranean

galley with oars as well as sails, each oar pulled by a slave who

kept time with his neighbor like a machine. The English made their

bid for fortune with the sailing-ship, and even in the twelfth

century, when their keels were rarely seen in any Eastern port, there

was little of the rule of wind and sea short of Gibraltar that their

captains did not know.

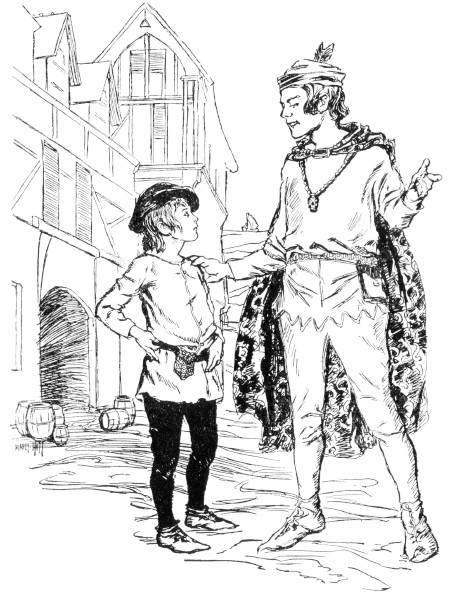

Up

Mart Lane, the steep little street from the wharves, Nicholas heard

some one singing a familiar chantey, but not as the sailors sang it.

He was a slender youth with a laugh in his eye, and he was singing to

a guitar-like lute. He was piecing out the chantey and fitting words

to it, and succeeding rather well. Nicholas stood by his father's

warehouse, hands behind him and eyes on the ship just edging out to

catch the tide, and listened to the song, his heart full of dreams.

"Hey,

there, youngster!" said the singer kindly as he reached the end

of the strophe. "Have you a share in that ship that you watch

her so sharply?"

"No,"

said Nicholas gravely, "she's not one of father's ships. She's

the Heath Hen of Weymouth, and she's loaded with wool, surely, but

she's for Bordeaux."

"Bless

the urchin, he might have been born on board!" The young man

looked at Nicholas rather more attentively. "Your father has

chips, then?"

Nicholas

nodded proudly. "The Rose-in-June, and the Sainte Spirite, and

the Thomasyn, she's named for mother, and the Sainte Genevieve,

because father was born in Paris, you know, and the Saint Nicholas,

that's named for me. But I'm not old enough to have a venture yet.

Father says I shall some day."

The

Pool of the Thames was crowded, and as the wind freshened the ships

looked even more like huge white-winged birds. Around them sailed and

wheeled and fluttered the real sea-birds, picking up their living

from the scraps thrown overboard, swans, gulls, wild geese and ducks,

here and there a strange bird lured to the harbor by hope of spoil.

The oddly mated companions, the man and the boy, walked along busy

Thames Street and came to Tower Hill and the great gray

fortress-towers, with a double line of wall coiled around the base,

just outside the City of London. The deep wide moat fed from the

river made an island for the group of buildings with the square White

Tower in the middle.

"None

of your friends live there, I supposed" the young man inquired,

and Nicholas smiled rather dubiously, for he was not certain whether

it was a joke or not. The Tower had been prison, palace and fort by

turns, but common criminals were not imprisoned there only those who

had been accused of crimes against the State. "Lucky you,"

the youth added. "London is much pleasanter as a residence, I

assure you. I lodged not far from here when I first came, but now I

lodge "

That

sentence was never finished. Clattering down Tower Hill came a troop

of horse, and one, swerving suddenly, caught Nicholas between his

heels and the wall, and by the time the rider had his animal under

control the little fellow was lying senseless in the arms of the

stranger, who had dived in among the flying hoofs and dragged him

clear. The rider, lagging behind the rest, looked hard at the two,

and then spurred on without even stopping to ask whether he had hurt

the boy.

Before

Nicholas had fairly come to himself he shut his teeth hard to keep

from crying out with the pain in his side and left leg. The young man

had laid him carefully down close by the wall, and just as he was

looking about for help three of the troopers came spurring back,

dismounted, and pressed close around the youth as one of them said

something in French. He straightened up and looked at them, and in

spite of his pain Nicholas could not help noticing that he looked

proudly and straightforwardly, as if he were a gentleman born. He

answered them in the same language; they shook their heads and made

gruff, short answers. The young man laid his hand on his dagger,

hesitated, and turned back to Nicholas.

"Little

lad," he said, "this is indeed bad fortune. They will not

let me take you home, but " So deftly that the action was hidden

from the men who stood by, he closed Nicholas' hand over a small

packet, while apparently he was only searching for a coin in his

pouch and beckoning to a respectable-looking market-woman who halted

near by just then. He added in a quick low tone without looking at

the boy, "Keep it for me and say nothing."

Nicholas

nodded and slipped the packet into the breast of his doublet, with a

groan which was very real, for it hurt him to move that arm. The

young man rose and as his captors laid heavy hands upon him he put

some silver in the woman's hand, saying persuasively, "This boy

has been badly hurt. I know not who he is, but see that he gets home

safely."

"Aye,

master," said the woman compassionately, and then everything

grew black once more before Nicholas' eyes as he tried to see where

the men were going. When he came to himself they were gone, and he

told the woman that he was Nicholas Gay and that his father was

Gilbert Gay, in Fenchurch Street. The woman knew the house, which was

tile-roofed and three-storied, and had a garden; she called a porter

and sent him for a hurdle, and they got Nicholas home.

The

merchant and his wife were seriously disturbed over the accident, not

only because the boy was hurt, and hurt in so cruel a way, but

because some political plot or other seemed to be mixed up in it.

From what the market-woman said it looked as if the men might have

been officers of the law, and it was her guess that the young man was

an Italian spy. Whatever he was, he had been taken in at the gates of

the Tower. In a city of less than fifty thousand people, all sorts of

gossip is rife about one faction and another, and if Gilbert Gay came

to be suspected by any of the King's advisers there were plenty of

jealous folk ready to make trouble for him and his. Time went by,

however, and they heard nothing more of it.

Nicholas

said nothing, even to his mother, of the packet which he had hidden

under the straw of his bed. It was sealed with a splash of red wax

over the silken knot that tied it, and much as he desired to know

what was inside, Nicholas had been told by his father that a seal

must never be broken except by the person who had a right to break

it. Gilbert Gay had also told his children repeatedly that if

anything was given to them, or told them, in confidence, it was most

wrong to say a word about it. It never occurred to Nicholas that

perhaps his father would expect him to tell of this. The youth had

told him not to tell, and he must not tell, and that was all about

it.

The

broken rib and the bruises healed in time, and by the season when the

Rose-in-June was due to sail, Nicholas was able to limp into the

rose-garden and play with his little sister Genevieve at sailing

rose-petal boats in the fountain. The time of loading the ships for a

foreign voyage was always rather exciting, and this was the best and

fastest of them all. When she came back, if the voyage had been

fortunate, she would be laden with spices and perfumes, fine silks

and linen, from countries beyond the sunrise where no one that

Nicholas knew had ever been. From India and Persia, Arabia and

Turkey, caravans of laden camels were even then bringing her cargo

across the desert. They would be unloaded in such great market-places

as Moussoul, Damascus, Bagdad and Cairo, the Babylon of those days.

Alexandria and Constantinople, Tyre and Joppa, were seaport

market-cities, and here the Venetian and Genoese galleys, or French

ships of Marseilles and Bordeaux, or the half-Saracen, half-Norman

traders of Messina came for their goods.

The

Rose-in-June would touch at Antwerp and unload wool for Flemish

weavers to make into fine cloth; she would cruise around the coast,

put in at Bordeaux, and sell the rest of her wool, and the grain of

which England also had a plenty. She might go on to Cadiz, or even

through the Straits of Gibraltar to Marseilles and Messina. The more

costly the stuff which she could pack into the hold for the homeward

voyage, the greater the profit for all concerned.

Since

wool takes up far more room in proportion to its value than silk,

wine or spices, money as well as merchandise must be put into the

venture, and the more money, the more profit. Others joined in the

venture with Master Gay. Edrupt the wool-merchant furnished a part of

the cargo on his own account; wool-merchants traveled through the

country as agents for Master Gay. The men who served in the warehouse

put in their share; even the porters and apprentices sent something,

if no more than a shilling. There was some profit also in the

passenger trade, especially in time of pilgrimage when it was hard to

get ships enough for all who wished to go. The night before the

sailing, Nicholas escaped from the happy hubbub and went slowly down

to the wharves. It was not a very long walk, but it tired him, and he

felt rather sad as he looked at the grim gray Tower looming above the

river, and wondered if the owner of the packet sealed with the red

seal would ever come back.

"Have

you been here all this time?"

As

he passed the little church at the foot of Tower Hill a light step

came up behind him, and two hands were placed on his shoulders.

"My

faith!" said the young man. "Have you been here all this

time?"

He

was thinner and paler, but the laughter still sparkled in his dark

eyes, and he was dressed in daintily embroidered doublet, fine hose,

and cloak of the newest fashion, a gold chain about his neck and a

harp slung from his shoulder. A group of well-dressed servants stood

near the church.

"I'm

well now," said Nicholas rather shyly but happily. "I'm

glad you have come back."

"I

was at my wit's end when I thought of you, lad," went on the

other, "for I remembered too late that neither of us knew the

other's name, and if I had told mine or asked yours in the hearing of

a certain rascal it might have been a sorry time for us both. They

made a little mistake, you see, they took me for a traitor."

"How

could they?" said Nicholas, surprised and indignant.

"Oh,

black is white to a scared man's eyes," said his companion

light-heartedly. "How have your father's ships prospered?'

"There's

one of them," Nicholas pointed, proudly, across the little space

of water, to the Rose-in-June tugging at her anchor.

"She's

a fine ship," the young man said consideringly, and then, as he

saw the parcel Nicholas was taking from his bosom, "Do you mean

to say that that has never been opened"? What sort of folk are

you?"

"I

never told," said Nicholas, somewhat bewildered. "You said

I was not to speak of it."

"And

there was no name on it, for a certain reason." The young man

balanced the parcel in his hand and whistled softly. "You see, I

was expecting to meet hereabouts a certain pilgrim who was to take

the parcel to Bordeaux, and beyond. I was interfered with, as you

know, and now it must go by a safe hand to one who -will deliver it

to this same pilgrim. I should say that your father must know how to

choose his captains."

"My

father is Master Gilbert Gay," Nicholas held his head very

straight "and that is Master Garland, the captain of the

Rose-in-June, coming ashore now."

"Oh,

I know him. I have had dealings with him before now. How would it be

since without your good help this packet would almost certainly have

been lost to let the worth of it be your venture in the cargo?"

"My

venture?" Nicholas stammered, the color rising in his cheeks.

"My venture?"

"It

is not worth much in money," the troubadour said with a queer

little laugh, "but it is something. Master Garland, I see you

have not forgotten me, Ranulph, called le Provencal. Here is a packet

to be delivered to Tomaso the physician of Padua, whom you know. The

money within is this young man's share in your cargo, and Tomaso will

pay you for your trouble."

Master

Garland grinned broadly in his big beard. "Surely, surely,"

he chuckled, and pocketed the parcel as if it had been an apple, but

Nicholas noted that he kept his hand on his pouch as he went on to

the wharf.

"And

now," Ranulph said, as there was a stir in the crowd by the

church door, evidently some one was coming out. "I must leave

you, my lad. Some day we shall meet again." Then he went hastily

away to join a brilliant company of courtiers in traveling attire.

Things were evidently going well with Ranulph.

Nicholas

thought a great deal about that packet in the days that followed. He

took to experimenting with various things to see what could account

for the weight. Lead was heavy, but no one would send a lump of lead

of that size over seas. The same could be said of iron. He bethought

him finally of a goldsmith's nephew with whom he had acquaintance.

Guy Bouverel was older, but the two boys knew each other well.

"Guy,"

he said one day, "what's the heaviest metal you ever handled?"

"Gold,"

said Guy promptly.

"A

bag that was too heavy to have silver in it would have gold?"

"I

should think so. Have you found treasure?"

"No,"

said Nicholas, "I was wondering."

The

Rose-in-June came back before she was due. Master Garland came up to

the house with Gilbert Gay, one rainy evening when Nicholas and

Genevieve were playing ninemen's-morris in a corner and their mother

was embroidering a girdle by the light of a bracket lamp. Nicholas

had been taught not to interrupt, and he did not, but he was glad

when his mother said gently, but with shining eyes, "Nicholas,

come here."

It

was a queer story that Captain Garland had to tell, and nobody could

make out exactly what it meant. Two or three years before he had met

Ranulph, who was then a troubadour in the service of Prince Henry of

Anjou, and he had taken a casket of gold pieces to Tomaso the

physician, who was then in Genoa.

"They

do say," said Captain Garland, pulling at his russet beard,

"that the old doctor can do anything short o' raising the dead.

They fair worshiped him there, I know. But it's my notion that that

box o' gold pieces wasn't payment for physic."

"Probably

not," said the merchant smiling. "Secret messengers are

more likely to deliver their messages if no one knows they have any.

But what happened this time?"

"Why,"

said the sea captain, "I found the old doctor in his garden,

with a great cat o' Malta stalking along beside him, and I gave him

the packet. He opened it and read the letter, and then he untied a

little leather purse and spilled out half a dozen gold pieces and

some jewels that fair made me blink not many, but beauties rubies and

emeralds and pearls. He beckoned toward the house and a man in

pilgrim's garb came out and valued the jewels. Then he sent me back

to the Rose-in-June with the worth o' the jewels in coined gold and

this ring here. 'Tell the boy,' says he, 'that he saved the King's

jewels, and that he has a better jewel than all of them, the jewel of

honor.'

"But,

father," said Nicholas, rather puzzled, "what else could I

do?'

None

of them could make anything of the mystery, but as Tomaso of Padua

talked with Eloy the goldsmith that same evening they agreed that the

price they paid was cheap. In the game the Pope's party was playing

against that of the Emperor for the mastery of Europe, it had been

deemed advisable to find out whether Henry Plantagenet would rule the

Holy Roman Empire if he could. He had refused the offer of the throne

of the Cæsars, and it was of the utmost importance that no one

should know that the offer had been made. Hence the delivery of the

letter to the jeweler.

|