THE CAGED BOUVEREL

I

am a little finch with wings of gold,

I

dwell within a cage upon the wall.

I

cannot fly within my narrow fold, —

I

eat, and drink, and sing, and that is all.

My

good old master talks to me sometimes,

But

if he knows my speech I cannot tell.

He

is so large he cannot sing nor fly,

But

he and I are both named Bouverel.

I

think perhaps he really wants to sing,

Because

the busy hammer that he wields

Goes

clinking light as merry bells that ring.

When

morris-dancers frolic in the fields,

And

this is what the music seems to tell

To

me, the finch, the feathered Bouverel.

"Kling-a-ling

— clack!

Masters,

what do ye lack?

Hammer

your heart in't, and strike with a knack!

Flackety

kling —

Biff,

batico, bing!

Platter,

cup, candlestick, necklace or ring!

Spare

not your labor, lads, make the gold sing, —

And

some day perhaps ye may work for the King!"

|

VI

AT

THE SIGN OF THE GOLD FINCH

HOW

GUY, THE GOLDSMITH'S APPRENTICE, WON THE DESIRE OF HIS HEART

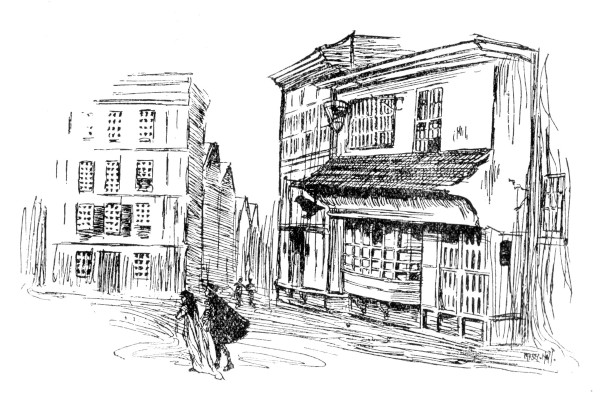

BANG — slam — bang-bang — slam! slam! slam!

If

anybody on the Chepe in the twelfth century had ever heard of

rifle-practice, early risers thereabouts might have been reminded of

the crackle of guns. The noise was made by the taking down of

shutters all along the shop fronts, and stacking them together out of

the way. The business day in London still begins in the same way, but

now there are plate-glass windows inside the shutters, and the shops

open between eight and nine instead of soon after daybreak.

It

was the work of the apprentices and the young sons of shop-keepers to

take down the shutters, sweep the floors, and put things in order for

the business of the day. This was the task which Guy, nephew of

Gamelyn the goldsmith, at the sign of the Gold Finch, particularly

liked. The air blew sweet and fresh from the convent gardens to the

eastward of the city, or up the river below London Bridge, or down

from the forest-clad hills of the north, and those who had the first

draft of it were in luck. London streets were narrow and twisty-wise,

but not overhung with coal smoke, for the city still burned wood from

the forests without the walls.

On

this May morning, Guy was among the first of the boys who tumbled out

from beds behind the counter and began to open the shops. The

shop-fronts were all uninclosed on the first floor, and when the

shutters were down the shop was separated from the street only by the

counter. Above were the rooms in which the shop-keeper and his family

lived, and the second story often jutted over the one below and made

a kind of covered porch. In some of the larger shops, like this one

of Goldsmiths' Row, the jewelers' street, there was a third story

which could be used as a storeroom. There were no glass cases or

glass windows. Lattices and shutters were used in window-openings,

and the goods of finer quality were kept in wooden chests. The shop

was also a work-room, for the shopkeeper was a manufacturer as well,

and a part if not all that he sold was made in his own house.

Guy,

having stacked away the shutters and taken a drink of water from the

well in the little garden at the rear, got a broom and began to sweep

the stone floor. It was like the brooms in pictures of witches, a

bundle of fresh twigs bound on the end of a stick, withes of supple

young willow being used instead of cord. Some of the twigs in the

broom had sprouted green leaves. Guy sang as he swept the trash out

into the middle of the street, but as a step came down the narrow

stair he hushed his song. When old Gamelyn had rheumatism the less

noise there was, the better. The five o'clock breakfast, a piece of

brown bread, a bit of herring and a horn cup of ale, was soon

finished, and then the goldsmith, rummaging among his wares, hauled a

leather sack out of a chest and bade Guy run with it to Ely House.

This

was an unexpected pleasure, especially for a spring morning as fair

as a blossoming almond tree. The Bishop of Ely lived outside London

Wall, near the road to Oxford, and his house was like a palace in a

fairy-tale. It had a chapel as stately as an ordinary church, a great

banquet-hall, and acres of gardens and orchards. No pleasanter place

could be found for an errand in May. Guy trotted along in great

satisfaction, making all the speed he could, for the time he saved on

the road he might have to look about in Ely House.

For

a city boy, he was extremely fond of country ways. He liked to walk

out on a holiday to Mile End between the convent gardens; he liked to

watch the squirrels flyte and frisk among the huge trees of Epping

Forest; he liked to follow at the heels of the gardener at Ely House

and see what new plant, shrub or seed some traveler from far lands

had brought for the Bishop. He did not care much for the city houses,

even for the finest ones, unless they had a garden. Privately he

thought that if ever he had his uncle's shop and became rich, and his

uncle had no son of his own, he would have a house outside the wall,

with a garden in which he would grow fruits and vegetables for his

table. Another matter on which his mind was quite made up was the

kind of things that would be made in the shop when he had it. The

gold finch that served for a sign had been made by his grandfather,

who came from Limoges, and it was handsomer than anything that Guy

had seen there in Gamelyn's day. Silver and gold work was often sent

there to be repaired, like the cup he had in the bag, a silver

wine-cup which the Bishop's steward now wanted at once; but Guy

wanted to learn to make such cups, and candlesticks, and finely

wrought banquet-dishes himself.

He

gave the cup to the steward and was told to come back for his money

after tierce, that is, after the service at the third hour of the

day, about half way between sunrise and noon. There were no clocks,

and Guy would know when it was time to go back by the sound of the

church bells. The hall was full of people coming and going on various

errands. One was a tired-looking man in a coarse robe, and broad hat,

rope girdle, and sandals, who, when he was told that the Bishop was

at Westminster on business with the King, looked so disappointed that

Guy felt sorry for him. The boy slipped into the garden for a talk

with his old friend the gardener, who gave him a head of new lettuce

and some young mustard, both of which were uncommon luxuries in a

London household of that day, and some roots for the tiny walled

garden which he and Aunt Joan were doing their best to keep up. As he

came out of the gate, having got his money, he saw the man he had

noticed before sitting by the roadside trying to fasten his sandal.

The string was worn out.

A

boy's pocket usually has string in it. Guy found a piece of leather

thong in his pouch and rather shyly held it out. The man looked up

with an odd smile.

"I

thank you," he said in curious formal English with a lisp in it.

"There is courtesy, then, among Londoners'? I began to think

none here cared for anything but money, and yet the finest things in

the world are not for sale."

Guy

did not know what to answer, but the idea interested him.

"The

sky above our heads," the wayfarer went on, looking with

narrowed eyes at the pink may spilling over the gray wall of the

Bishop's garden, "flowers, birds, music, these are for all. When

you go on pilgrimage you find out how pleasant is the world when you

need not think of gain.'

The

stranger was a pilgrim, then. That accounted for the clothes, but old

Gamelyn had been on pilgrimage to the new shrine at Canterbury, and

it had not helped his rheumatism much, and certainly had given him no

such ideas as these. Guy looked up at the weary face with the

brilliant eyes and smile, they were walking together now, and

wondered.

"And

what do you in London?" the pilgrim asked.

"My

uncle is a goldsmith in Chepe," said the boy.

"And

are you going to be a goldsmith in Chepe too?"

"I

suppose so."

"Then

you like not the plan?"

Guy

hesitated. He never had talked of his feeling about the business, but

he felt that this man would see what he meant. "I should like it

better than anything," he said, "if we made things like

those the Bishop has. Uncle Gamelyn says that there is no profit in

them, because they take the finest metal and the time of the best

workmen, and the pay is no more, and folk do not want them."

"My

boy," said the pilgrim earnestly, "there are always folk

who want the best. There are always men who will make only the best,

and when the two come together "

He

clapped his hollowed palms like a pair of cymbals. "Would you

like to make a dish as blue as the sea, with figures of the saints in

gold work and jewel-work a gold cup garlanded in flowers all done in

their own color, a shrine threefold, framing pictures of the saints

and studded with orfrey-work of gold and gems, yet so beautiful in

the mere work that no one would think of the jewels'? Would you"?"

"Would

I!" said Guy with a deep quick breath.

"Our

jewelers of Limoges make all these, and when kings and their armies

come from the Crusades they buy of us thank-offerings, candlesticks,

altar-screens, caskets, chalices, gold and silver and enamel-work of

every kind. We sit at the cross-roads of Christendom. The jewels come

to us from the mines of East and West. Men come to us with full

purses and glad hearts, desiring to give to the Church costly gifts

of their treasure, and our best work is none too good for their

desire. But here we are at Saint Paul's. I shall see you again, for I

have business on the Chepe."

Guy

headed for home as eagerly as a marmot in harvest time, threading his

way through the crowds of the narrow streets without seeing them. He

could not imagine who the stranger might be. It was dinner time, and

he had to go to the cook-shop and bring home the roast, for families

who could afford it patronized the cook-shops on the Thames instead

of roasting and baking at home in the narrow quarters of the shops.

In the great houses, with their army of servants and roomy kitchens,

it was different; and the very poor did what they could, as they do

everywhere; but when the wife and daughters of the shopkeeper served

in the shop, or worked at embroidery, needle-craft, weaving, or any

light work of the trade that they could do, it was an economy to have

the cooking done out of the house.

When

the shadows were growing long and the narrow pavement of Goldsmith's

Row was quite dark, some one wearing a gray robe and a broad hat came

along the street, slowly, glancing into each shop as he passed. To

Guy's amazement, old Gamelyn got to his feet and came forward.

"Is

it is it thou indeed, master?" he said, bowing again and again.

The pilgrim smiled.

"A

fine shop you have here," he said, "and a fine young bird

in training for the sign of the Gold Finch. He and I scraped

acquaintance this morning. Is he the youth of whom you told me when

we met at Canterbury?"

It

was hard on Guy that just at that moment his aunt Joan called him to

get some water from the well, but he went, all bursting with

eagerness as he was. The pilgrim stayed to supper, and in course of

time Guy found out what he had come for.

He

was Eloy, one of the chief jewelers of Limoges, which in the Middle

Ages meant that his work was known in every country of Europe, for

that city had been as famous for its gold work ever since the days of

Clovis as it is now for porcelain. Enamel-work was done there as

well, and the cunning workmen knew how to decorate gold, silver, or

copper in colors like vivid flame, living green, the blue of summer

skies. Eloy offered to take Guy as an apprentice and teach him all

that he could for the sake of the maker of the Gold Finch, who had

been his own good friend and master. It was as if the head of one of

the great Paris studios should offer free training for the next ten

years to some penniless art student of a country town.

What

amazed Guy more than anything else, however, was the discovery that

his grumbling old uncle, who never had had a good word to say for him

in the shop, had told this great artist about him when they met five

years before, and begged Eloy if ever he came to London to visit the

Gold Finch and see the little fellow who was growing up there to

learn the ancient craft in a town where men hardly knew what good

work was. Even now old Gamelyn would only say that his nephew was a

good boy and willing, but so painstaking that he would never make a

tradesman; he spent so much unnecessary time on his work.

"He

may be an artist," said Eloy with a smile; and some specimens of

the work which Guy did when he was a man, which are now carefully

kept in museums, prove that he was. No one knows how the enamel-work

of Limoges was done; it is only clear that the men who did it were

artists. The secret has long been lost ever since the city, centuries

ago, was trampled under the feet of war.

|