| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XIV ON THE PLATEAU TO THE FARTHEST SOUTH DECEMBER 18, 1908 TO JANUARY 8, 1909 December 21, Midsummer Day, with 28° of Frost: Christmas Day at an Altitude of 9500 ft. in Latitude 85° 55' South: Christmas Fare: Last Depot on January 4: Blinding Blizzard for two Days, January 7, 8: Altitude 11,600 ft. December

18.

Almost up: The altitude to-night is 7400 ft. above sea-level. This has

been one

of our hardest days, but worth it, for we are just on the plateau at

last. We

started at 7.30 A.M., relaying the sledges, and did 6 miles 600 yards,

which

means nearly 19 miles for the day of actual travelling. All tae morning

we

worked up loose, slippery ice, hauling the sledges up one at a time by

means of

the alpine rope, then pulling in harness on the less stiff rises. We

camped for

lunch at 12.45 P.M. on the crest of a rise close to the pressure and in

the

midst of crevasses, into one of which I managed to fall, also Adams.

Whilst

lunch was preparing I got some rock from the land, quite different to

the

sandstone of yesterday. The mountains are all different just here. The

land on

our left shows beautifully clear stratified lines, and on the west side

sandstone stands out, greatly weathered. All the afternoon we relayed

up a long

snow slope, and we were hungry and tired when we reached camp. We have

been

saving food to make it spin out, and that increases our hunger; each

night we

all dream of foods. We save two biscuits per man per day, also pemmican

and

sugar, eking out our food with pony maize, which we soak in water to

make it

less hard. All this means that we have now five weeks' food, while we

are about

300 geographical miles from the Pole, with the same distance back to

the last

depot we left yesterday, so we must march on short food to reach our

goal. The

temperature is plus 16° Fahr. to-night, but a cold wind all the morning

out our

faces and broken lips. We keep crevasses with us still, but I think

that

to-morrow will see the end of this. When we passed the main slope

to-day, more

mountains appeared to the west of south, some with sheer cliffs and

others

rounded off, ending in long snow slopes. I judge the southern limit of

the

mountains to the west to be about latitude 86° South. December

19.

Not on the plateau level yet, though we are to-night 7888 ft. up, and

still

there is another rise ahead of us. We got breakfast at 5 A.M. and

started at 7 A.M.

sharp, taking on one sledge. Soon we got to the top of a ridge, and

went back

for the second sledge, then hauled both together all the rest of the

day. The

weight was about 200 lb. per man, and we kept going until 6 P.M., with

a stop

of one hour for lunch. We got a meridian altitude at noon, and found

that our

latitude was 85° 5' South. We seem unable to get rid of the crevasses,

and we

have been falling into them and steering through them all day in the

face of a

cold southerly wind, with a temperature varying from plus 15° to plus

9° Fahr.

The work was very heavy, for we were going uphill all day, and our

sledge

runners, which have been suffering from the sharp ice and rough

travelling, are

in a bad way. Soft snow in places greatly retarded our progress, but we

have

covered our ten miles, and now are camped on good snow between two

crevasses. I

really think that to-morrow will see us on the plateau proper. This

glacier

must be one of the largest, if not the largest, in the world. The

sastrugi seem

to point mainly to the south, so we may expect head winds all the way

to the

Pole. Marshall has a cold job to-night, taking the angles of the new

mountains

to the west, some of which appeared to-day. After dinner we examined

the sledge

runners and turned one sledge end for end, for it had bees badly torn

while we

were coming up the glacier, and in the soft snow it clogged greatly. We

are

still favoured with splendid weather, and that is a great comfort to

us, for it

would be almost impossible under other conditions to travel amongst

these

crevasses, which are caused by the congestion of the ice between the

headlands

when it was flowing from the plateau down between the mountains. Now

there is

comparatively little movement, and many of the crevasses have become

snow-filled. To-night we are 290 geographical miles from the Pole. We

are

thinking of our Christmas dinner. We will be full that day, anyhow. December

20.

Not yet up, but nearly so. We got away from camp at 7 A.M., with a

strong head

wind from the south, and this wind continued all day, with a

temperature

ranging from plus 7° to plus 5°. Our beards coated with ice. It was an

uphill

pull all day around pressure ice, and we reached an altitude of over

8000 ft.

above sea-level. The weather was clear, but there were various clouds,

which

were noted by Adams. Marshall took bearings and angles at noon, and we

got the

sun's meridian altitude, showing that we were in latitude 85° 17'

South. We

hope all the time that each ridge we come to will be the last, but each

time

another rises ahead, split up by pressure, and we begin the same toil

again. It

is trying work and as we have now reduced our food at breakfast to one

pannikin

of hoosh and one biscuit, by the time the lunch hour has arrived, after

five

hours' hauling in the cold wind up the slope, we are very hungry. At

lunch we

have a little chocolate, tea with plasmon, a pannikin of cocoa, and

three

biscuits. To-day we did 11 miles, 950 yards (statute), having to relay

the

sledges over the last bit, for the ridge we were on was so steep that

we could

not get the two sledges up together. Still, we are getting on; we have

only 279

more miles to go, and then we will have reached the Pole. The land

appears to

run away to the south-east now, and soon we will be just a speck on

this great

inland waste of snow and ice. It is cold to-night. I am cook for the

week, and

started to-night. Every one is fit and well. December

21.

Midsummer Day, with 28° of frost! We have frost-bitten fingers and

ears, and a

strong blizzard wind has been blowing from the south all day, all due

to the

fact that we have climbed to an altitude of over 8000 ft. above

sea-level. From

early morning we have been striving to the south, but six miles is the

total

distance gained, for from noon, or rather from lunch at 1 P.M., we have

been

hauling the sledges up, one after the other, by standing pulls across

crevasses

and over great pressure ridges. When we had advanced one sledge some

distance,

we put up a flag on a bamboo to mark its position, and then roped up

and

returned for the other. The wind, no doubt, has a great deal to do with

the low

temperature, and we feel the cold, as we are going on short commons.

The

altitude adds to the difficulties, but we are getting south all the

time. We

started away from camp at 6.45 A.M. to-day, and except for an hour's

halt at

lunch, worked on until 6 P.M. Now we are camped in a filled-up

crevasse, the

only place where snow to put round the tents oan be obtained, for all

the rest.

of the ground we are on is either nevO or hard ice. We little thought

that this

particular pressure ridge was going to be such an obstacle; it looked

quite

ordinary, even a short way off, but we have now decided to trust

nothing to

eyesight, for the distances are so deceptive up here. It is a wonderful

sight

to look down over the glacier from the great altitude we are at, and to

see the

mountains stretching away east and west, some of them over 15,000 ft.

in

height. We are very hungry now, and it seems as cold almost as the

spring

sledging. Our beards are masses of ice all day long. Thank God we are

fit and

well and have had no accident, which is a mercy, seeing that we have

covered

over 130 miles of crevassed ice. December

22.

As I write of to-day's events, I can easily imagine I am on a spring

sledging

journey, for the temperature is minus 5° Fahr. and a chilly

south-easterly wind

is blowing and finds its way through the walls of our tent, which are

getting

worn. All day long, from 7 A.M., except for the hour when we stopped

for lunch,

we have been relaying the sledges over the pressure mounds and across

crevasses. Our total distance to the good for the whole day was only

four miles

southward, but this evening our prospects look brighter, for we must

now have

come to the end of the great glacier. It is flattening out, and except

for

crevasses there will not be much trouble in hauling the sledges

to-morrow. One

sledge to-day, when coming down with a run over a pressure ridge,

turned a

complete somersault, but nothing was damaged, in spite of the total

weight

being over 400 lb. We are now dragging 400 lb. at a time up the steep

slopes

and across the ridges, working with the alpine rope all day, and roping

ourselves together when we go back for the second sledge, for the

ground is so

treacherous that many times during the day we are saved only by the

rope from

falling into fathomless pits. Wild describes the sensation of walking

over this

surface, half ice and half snow, as like walking over the glass roof of

a

station. The usual query when one of us falls into a crevasse is!" Have

you found it?" One gets somewhat callous as regards the immediate

danger,

though we are always glad to meet crevasses with their coats off, that

is, not

hidden by the snow covering. To-night we are camped in a filled-in

crevasse.

Away to the north down the glacier a thick cumulus cloud is lying, but

some of

the largest mountains are standing out clearly. Immediately behind us

lies a

broken sea of pressure ice. Please God, ahead of us there is a clear

road to

the Pole. December

23.

Eight thousand eight hundred and twenty feet ip, and still steering

upwards

amid great waves of pressure and ice-falls, for our plateau, after a

good

morning's march, began to rise in higher ridges, so that it really was

not the

plateau after all. To-day's crevasses have been far more dangerous than

any

others we have crossed, as the soft snow hides all trace of them until

we fall

through. Constantly to-day one or another of the party has had to be

hauled out

from a chasm by means of his harness, which had alone saved him from

death in

the icy vault below. We started at 6.40 A.M. and worked on steadily

until 6

P.M., with the usual lunch hour in the middle of the day. The pony

maize does

not swell in the water now, as the temperature is very low and the

water

freezes. The result is that it swells inside after we have eaten it. We

are

very hungry indeed, and talk a rest deal of what we would like to eat.

In spite

of the crevasses, we have done thirteen miles to-day to the south, and

we are

now in latitude 85° 41' South. The temperature at noon was plus 6°

Fahr. and at

6 P.M. it was minus 1° Fahr., but it is much lower at night. There was

a strong

south-east to south-south-east wind blowing all day, and it was cutting

to our

noses and burst lips. Wild was frost-bitten. I do trust that tomorrow

will see

the end of this bad travelling, so that we can stretch out our legs for

the

Pole. December

24.

A much better day for us; indeed, the brightest we have had since

entering our

Southern Gateway. We started off at 7 A.M. across waves and undulations

of ice,

with some one or other of our little party falling through the thin

crust of

snow every now and then. At 10.30 A.M. I decided to steer more to the

west, and

we soon got on to a better surface, and covered 5 miles 250 yards in

the

forenoon. After lunch, as the surface was distinctly improving, we

discarded

the second sledge, and started our afternoon's march with one sledge.

It has

been blowing freshly from the south and drifting all day, and this,

with over

40° of frost, has coated our faces with ice. We get superficial

frost-bites

every now and then. During the afternoon the surface improved greatly,

and the

cracks and crevasses disappeared, but we are still going uphill, and

from the

summit of one ridge saw some new land, which runs south-south-east down

to

latitude 86° South. We camped at 6 P.M., very tired and with cold feet.

We have

only the clothes we stand up in now, as we depoted everything else, and

this

continued rise means lower temperatures than I had anticipated.

To-night we are

9095 ft. above sea-level, and the way before us is still rising. I

trust that

it will soon level out, for it is hard work pulling at this altitude.

So far

there is no sign of the very hard surface that Captain Scott speaks of

in

connection with his journey on the Northern Plateau. There seem to be

just here

regular layers of snow, not much wind-swept, but we will see better the

surface

conditions in a few days. To-morrow will be Christmas Day, and our

thoughts

turn to home and all the attendant joys of the time. One longs to hear

"the

hansoms slurring through the London mud." Instead of that, we are lying

in

a little tent, isolated high on the roof of the end of the world, far,

indeed,

from the ways trodden of men. Still, our thoughts can fly across the

wastes of

ice and snow and across the oceans to those whom we are striving for

and who

are thinking of us now. And, thank God, we are nearing our goal. The

distance

covered to-day was 11 miles 250 yards. December 25.

Christmas Day. There

has been from 45° to 48° of frost, drifting snow and a strong biting

south

wind, and such has been the order of the day's march from 7 A.M. to 6

P.M. up

one of the steepest rises we have yet done, crevassed in places. Now,

as I

write, we are 9500 ft. above sea-level, and our latitude at 6 P.M. was

85° 55'

South. We started away after a good breakfast, and soon came to soft

snow,

through which our worn and torn sledge-runners dragged heavily. All

morning we

hauled along, and at noon had done 5 miles 250 yards. Sights gave us

latitude

85° 51' South. We had lunch then, and I took a photograph of the camp

with the

Queen's flag flying and also our tent flags, my companions being in the

picture. It was very cold, the temperature being minus 16° Fahr., and

the wind

went through us. All the afternoon we worked steadily uphill, and we

could see

at 6 P.M. the new land plainly trending to the southeast. This land is

very

much glaciated. It is comparatively bare of snow, and there are

well-defined

glaciers on the side of the range, which seems to end up in the

south-east with

a large mountain like a keep. We have called it "The Castle." Behind

these the mountains have more gentle slopes and are more rounded. They

seem to

fall away to the south-east, so that, as we are going south, the angle

opens

and we will soon miss them. When we camped at 6 P.M. the wind was

decreasing.

It is hard to understand this soft snow with such a persistent wind,

and I can

only suppose that we have not yet reached the actual plateau level, and

that

the snow we are travelling over just now is on the slopes, blown down

by the

south and south-east wind. We had a splendid dinner. First came hoosh,

consisting of pony ration boiled up with pemmican and some of our

emergency Oxo

and biscuit. Then in the cocoa water I boiled our little plum pudding,

which a

friend of Wild's had given him. This, with a drop of medical brandy,

was a

luxury which Lucullus himself might have envied; then came cocoa, and

lastly

cigars and a spoonful of creme de menthe sent us by a friend in

Scotland. We

are full to-night, and this is the last time we will be for many a long

day.

After dinner we discussed the situation, and we have decided to still

further

reduce our food. We have now nearly 500 miles, geographical, to do if

we are to

get to the Pole and back to the spot where we are at the present

moment. We

have one months' food, but only three weeks' biscuit, so we are going

to make

each week's food last ten days. We will have one biscuit in the

morning, three

at mid-day, and two at night. It is the only thing to do. To-morrow we

will

throw away everything except the most absolute necessities. Already we

are, as

regards clothes, down to the limit, but we must trust to the old

sledge-runners

and dump the spare ones. One must risk this. We are very far away from

all the

world, and home thoughts have been much with us to-day, thoughts

interrupted by

pitching forward into a hidden crevasse more than once. Ah, well, we

shall see

all our own people when the work here is done. Marshall took our

temperatures

to-night. We are all two degrees sub normal, but as fit as can be. It

is a fine

open-air life and we are getting south. December

26.

Got away at 7 A.M. sharp, after dumping a lot of gear. We marched

steadily all

day except for lunch, and we have done 14 miles 480 yards on an uphill

march,

with soft snow at times and a bad wind. Ridge after ridge we met, and

though

the surface is better and harder in places, we feel very tired at the

end of

ten hours' pulling. Our height to-night is 9590 ft. above sea-level

according

to the hypsometer. The ridges we meet with are almost similar in

appearance. We

see the sun shining on them in the distance, and then the rise begins

very

gradually. The snow gets soft, and the weight of the sledge becomes

more

marked. As we near the top the soft snow gives place to a hard surface,

and on

the summit of the ridge we find small crevasses. Every time we reach

the top of

a ridge we say to ourselves: "Perhaps this is the last," but it never

is the last; always there appears away ahead of us another ridge. I do

not

think that the land lies very far below the ice-sheet, for the

crevasses on the

summits of the ridges suggest that the sheet is moving over land at no

great

depth. It would seem that the descent towards the glacier proper from

the

plateau is by a series of terraces. We lost sight of the land to-day,

having

left it all behind us, and now we have the waste of snow all around.

Two more

days and our maize will be finished. Then our hooshes will be more

woefully

thin than ever. This shortness of food is unpleasant, but if we allow

ourselves

what, under ordinary circumstances, would be a reasonable amount, we

would have

to abandon all idea of getting far south. December

27.

If a great snow plain, rising every seven miles in a steep ridge, can

be called

a plateau, then we are on it at last, with an altitude above the sea of

9820

ft. We started at 7 A.M. and marched till noon, encountering at 11 A.M.

a steep

snow ridge which pretty well cooked us, but we got the sledge up by

noon and

camped. We are pulling 150 lb. per man. In the afternoon we had good

going till

5 P.M. and then another ridge as difficult as the previous one, so that

our

backs and legs were in a bad way when we reached the top at 6 P.M.,

having done

14 miles 930 yards for the day. Thank heaven it has been a fine day,

with

little wind. The temperature is minus 93 Fehr. This surface is most

peculiar,

showing layers of snow with little sastrugi all pointing

south-south-east.

Short food make us think of plum puddings, and hard half-cooked maize

gives us

indigestion, but we are getting south. The latitude is 86° 19' South

to-night.

Our thoughts are with the people at home a great deal. December

28.

If the Barrier is a changing sea, the plateau is a changing sky. During

the

morning march we continued to go up hill steadily, but the surface was

constantly changing. First there was soft snow in layers, then soft

snow so

deep that we were well over our ankles, and the temperature being well

below

zero, our feet were cold through sinking in. No one can say what we are

going

to find next, but we can go steadily ahead. We started at 6.55 A.M.,

and had

done 7 miles 200 yards by noon, the pulling being very hard. Some of

the snow

is blown into hard sastrugi, some that look perfectly smooth and hard

have only

a thin crust through which we break when pulling; all of it is a

trouble.

Yesterday we passed our last crevasse, though there are a few cracks or

ridges

fringed with crystals shining like diamonds, warning us that the cracks

are

open. We are now 10,199 ft. above sea-level, and the plateau is

gradually

flattening out, but it was heavy work pulling this afternoon. The high

altitude

and a temperature of 48° of frost made breathing and work difficult. We

are

getting south — latitude 86° 31' South to-night. The last sixty miles

we hope

to rush, leaving everything possible, taking one tent only and using

the poles

of the other as marks every ten miles, for we will leave all our food

sixty

miles off the Pole except enough to carry us there and back. I hope

with good

weather to reach the Pole on January 12, and then we will try and rush

it to

get to Hut Point by February 28. We are so tired after each hour's

pulling that

we throw ourselves on our backs for a three minutes' spell. It took us

over ten

hours to do 14 miles 450 yards to-day, but we did it all right. It is a

wonderful thing to be over 10,000 ft. up, almost at the end of the

world. The

short food is trying, but when we have done the work we will be happy.

Adams

had a bad headache all yesterday, and to-day I had the same trouble,

but it is

better now. Otherwise we are all fit and well. I think the country is

flattening out more and more, and hope to-morrow to make fifteen miles,

at

least. December

29.

Yesterday I wrote that we hoped to do fifteen miles to-day, but such is

the

variable character of this surface that one cannot prophesy with any

certainty

an hour ahead. A strong southerly wind, with from 44° to 49° of frost,

combined

with the effect of short rations, made our distance 12 miles 600 yards

instead.

We have reached an altitude of 10,310 ft., and an uphill gradient gave

us one

of the most severe pulls for ten hours that would be possible. It looks

serious, for we must increase the food if we are to get on at all, and

we must

risk a depot at seventy miles off the Pole and dash for it then. Our

sledge is

badly strained, and on the abominably bad surface of soft snow is

dreadfully

hard to move. I have been suffering from a bad headache all day, and

Adams also

was worried by the cold. I think that these headaches are a form of

mountain

sickness, due to our high altitude. The others have bled from the nose,

and

that must relieve them. Physical effort is always trying at a high

altitude,

and we are straining at the harness all day, sometimes slipping in the

soft

snow that overlies the hard sastrugi. My head is very bad. The

sensation is as

though the nerves were being twisted up with a corkscrew and then

pulled out.

Marshall took our temperatures to-night, and we are all at about 94°,

but in

spite of this we are getting south. We are only 198 miles off our goal

now. If

the rise would stop the cold would not matter, but it is hard to know

what is

man's limit. We have only 150 lb. per man to pull, but it is more

severe work

thank the 250 lb. per man up the glacier was. The Pole is hard to get. December

30.

We only did 4 miles 100 yards to-day. We started at 7 A.M., but had to

camp at

11 A.M., a blizzard springing up from the south. It is more than

annoying. I

cannot express my feelings. We were pulling at last on a level surface,

but

very soft snow, when at about 10 A.M. the south wind and drift

commenced to

increase, and at 11 A.M. it was so bad that we had to *amp. And here

all day we

have been lying in our sleeping-bags trying to keep warm and listening

to the

threshing drift on the tent-side. I am in the cooking-tent, and the

wind comes

through, it is so thin. Our precious food is going and the time also,

and it is

so important to us to get on. We lie here and think of how to make

things

better, but we cannot reduce food now, and the only thing will be to

rush all

possible at the end. We will do and are doing all humanly possible. It

is with

Providence to help us. December

31.

The last day of the old year, and the hardest day we have had almost,

pushing

through soft snow uphill with a strong head wind and drift all day. The

temperature is minus 7° Fahr., and our altitude is 10,477 ft. above

sea-level.

The altitude is trying. My head has been very bad all day, and we are

all

feeling the short food, but still we are getting south. We are in

latitude 86°

54' South to-night, but we have only three weeks' food and two weeks'

biscuit

to do nearly 500 geographical miles. We can only do our best. Too tired

to write

more to-night. We all get iced-up about our faces, and are on the verge

of

frost-bite all the time. Please God the weather will be fine during the

next

fourteen days. Then all will be well. The distance to-day was eleven

miles. NOTE. If we had

only known that we

were going to get such cold weather as we were at this time

experiencing, we

would have kept a pair of scissors to trim our beards. The moisture

from the

condensation of one's breath accumulated on the beard and trickled down

on to

the Burberry blouse. Then it froze into a sheet of ice inside, and it

became

very painful to pull the Burberry off in camp. Little troubles of this

sort

would have seemed less serious to us if we had been able to get a

decent feed

at the end of the day's work, but we were very hungry. We thought of

food most

of the time. The chocolate certainly seemed better than the cheese,

because the

two spoonfuls of cheese per man allowed under our scale of diet would

not last

as long as the two sticks of chocolate. We did not have both at the

same meal. We had the bad

luck at this time to

strike a tin in which the biscuits were thin and overbaked. Under

ordinary

circumstances they would probably have tasted rather better than the

other

biscuits, but we wanted bulk. We soaked them in our tea so that they

would

swell up and appear larger, but if one soaked a biscuit too much, the

sensation

of biting something was lost, and the food seemed to disappear much too

easily. January 1,

1909.

Head too bad

to write much. We did 11 miles 900 yards (statute) to-day,

and the latitude at 6 P.M. was 87° 6' South, so we have beaten North

and South

records. Struggling uphill all day in very soft snow. Every one done up

and

weak from want of food. When we camped at 6 P.M. fine warm weather,

thank God.

Only 1721 miles from the Pole. The height above sea-level, now 10,755

ft.,

makes all work difficult. Surface seems to be better ahead. I do trust

it will

be so to-morrow. January 2.

Terribly hard work to-day. We starteli at 6.45 et.m. with a fairly good

surface, which soon became very soft. We were sinking in over our

ankles, and

our broken sledge, by running sideways, added to the drag. We have been

going

uphill all day, and to-night are 11,034 ft. above sea-level. It has

taken us

all day to do 10 miles 450 yards, though the weights are fairly light.

A cold

wind, with a temperature of minus 14° Fahr., goes right through us now,

as we

are weakening from want of food, and the high altitude makes every

movement an

effort, especially if we stumble on the march. My head is giving me

trouble all

the time. Wild seems the most fit of us. God knows we are doing all we

can, but

the outlook is serious if this surface ciptinues and the plateau gets

higher,

for we are not travelling fast enough to make our food spin out and get

back to

our depot in time. I cannot think of failure yet. I must look at the

matter

sensibly and consider the lives of those who are with me. I feel that

if we go

on too far it will be impossible to get back over this surface, and

then all the

results will be lost to the world. We can now definitely locate the

South Pole

on the highest. plateau in the world, and our geological work and

meteorology

will be of the greatest use to science; but all this is not the Pole.

Man can

only do his best, and we have arrayed against us the strongest forces

of

nature. This cutting south wind with drift plays the mischief with us,

and

after ten hours of struggling against it one pannikin of food with two

biscuits

and a cap of cocoa does not warm one up much. I must think over the

situation

carefully to-morrow, for time is going on and food is going also. January 3.

Started at 6.55 A.M., cloudy but fairly warm. The temperature was minus

8°

Fahr. at noon. We had a terrible surface all the morning, and did only

5 miles

100 yards. A meridian altitude gave us latitude 87° 22' South at noon.

The

surface was better in the afternoon, and we did six geographical miles.

The

temperature at 6 P.M. was minus 11° Fahr. It was an uphill pull towards

the

evening, and we camped at 6.20 P.M., the altitude being 11,220 ft.

above the

sea. To-morrow we must risk making a depot on the plateau, and make a

dash for

it, but even then, if this surface continues, we will be two weeks in

carrying

it through.

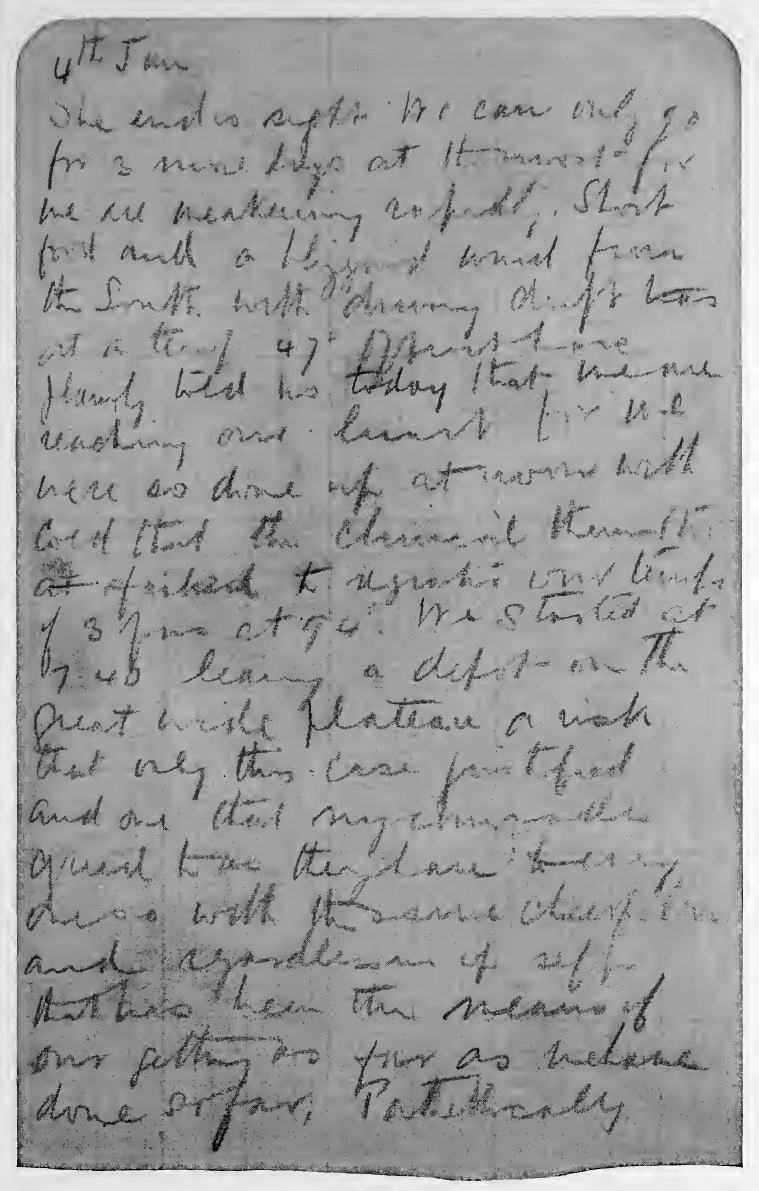

FACSIMILE OF PAGE OF SHACKLETON'S DIARY January 4.

The end is in sight. We can only go for three more days at the most,

for we are

weakening rapidly. Short food and a blizzard wind from the south, with

driving

drift, at a temperature of 47° of frost, have plainly told us to-day

that we

are reaching our limit, for we were so done up at noon with cold that

the

clinical thermometer failed to register the temperature of three of us

at 94°.

We started at 7.40 A.M., leaving a depot on this great wide plateau, a

risk

that only this case justified, and one that my comrades agreed to, as

they have

to every one so far, with the same cheerfulness and regardlessness of

self that

have been the means of our getting as far as we have done so far.

Pathetically

small looked the bamboo, one of the tent poles, with a bit of bag sewn

on as a

flag, to mark our stock of provisions, which has to take us back to our

depot,

one hundred and fifty miles north. We lost sight of it in half an hour,

and are

now trusting to our footprints in the snow to guide us back to each

bamboo

until we pick up the depot again. I trust that the weather will keep

clear.

To-day we have done 12½ geographical miles, and with only 70 lb. per

man to

pull it is as hard, even harder, work than the 100 odd lb. was

yesterday, and

far harder than the 250 lb. were three weeks ago, when we were climbing

the

glacier. This, I consider, is a clear indication of our failing

strength. The

main thing against us is the altitude of 11,200 ft. and the biting

wind. Our

faces are cut, and our feet and hands are always on the verge of

frost-bite. Our

fingers, indeed, often go, but we get them round more or less. I have

great

trouble with two fingers on my left hand. They had been badly jammed

when we

were getting the motor up over the

ice face at

winter quarters, and the circulation is not

good. Our boots now are pretty well worn out, and we have to halt at

times to

pick the snow out of the soles. Our stock of sennegrass is nearly

exhausted, so

we have to use the same frozen stuff day after day. Another trouble is

that the

lamp-wick with which we tie the finnesko is chafed through, and we have

to tie

knots in it. These knots catch the snow under our feet, making a lump

that has

to be cleared every now and then. I am of the opinion that to sledge

even in the

height of summer on this plateau, we should have at least forty ounces

of food

a day per man, and we are on short rations of the ordinary allowance of

thirty-two ounces. We depoted our extra underclothing to save weight

about

three weeks ago, and are now in the same clothes night and day. One

suit of

underclothing, shirt and guernsey, and our thin Burberries, now all

patched.

When we get up in the morning, out of the wet bag, our Burberries

become like a

coat of mail at once, and our heads and beards get iced-up with the

moisture

when breathing on the march. There is half a gale blowing dead in our

teeth all

the time. We hope to reach within 100 geographical miles of the Pole;

under the

circumstances we can expect to do very little more. I am confident that

the

Pole lies on the great plateau we have discovered, miles and miles from

any

outstanding land. The temperature tonight is minus 24° Fahr. January 5.

To-day head wind and drift again, with 50° of frost, and a terrible

surface. We

have been marching through 8 in. of snow, covering sharp sastrugi,

which plays

havoc with our feet, but we have done 131 geographical miles, for we

increased

our food, seeing that it was absolutely necessary to do this to enable

us to

accomplish anything. I realise that the food we have been having has

not been

sufficient to keep up our strength, let alone supply the wastage caused

by

exertion, and now we must try to keep warmth in us, though our strength

is

being used up. Our temperatures at 5 A.M. were 94° Fahr. We got away at

7 A.M.

sharp and marched till noon, then from 1 P.M. sharp till 6 P.M. All

being in

one tent makes our camp-work slower, for we are so cramped for room,

and we get

up at 4.40 A.M. so as to get away by 7 A.M. Two of us have to stand

outside the

tent at night until things are squared up inside, and we find it cold

work.

Hunger grips us hard, and the food-supply is very small. My head still

gives me

great trouble. I began by wishing that my worst enemy had it instead of

myself,

but now I don't wish even my worst enemy to have such a headache;

still, it is

no use talking about it. Self is a subject that most of us are fluent

on. We

find the utmost difficulty in carrying through the day, and we can only

go for

two or three more days. Never once has the temperature been above zero

since we

got on to the plateau, though this is the height of summer. We have

done our

best, and we thank God for having allowed us to get so far. January 6.

This must be our last outward march with the sledge and camp equipment.

To-morrow

we must leave camp with some food, and push as far south as possible,

and then

plant the flag. To-day's story is 57° of frost, with a strong blizzard

and high

drift; yet we marched 13i geographical miles through soft snow, being

helped by

extra food. This does not mean full rations, but a bigger ration than

we have

been having lately. The pony maize is all finished. The most trying day

we have

yet spent, our fingers and faces being frost-bitten continually.

To-morrow we

will rush south with the flag. We are at 88° 7' South to-night. It is

our last

outward march. Blowing hard to-night. I would fail to explain my

feelings if I

tried to write them down, now that the end has come. There is only one

thing

that lightens the disappointment, and that is the feeling that we have

done all

we could. It is the forces of nature that have prevented us from going

right

through. I cannot write more. January 7. A

blinding, shrieking blizzard all day, with the temperature ranging from

60° to

70° of frost. It has been impossible to leave the tent, which is snowed

up on

the lee side. We have been lying in our bags all day, only warm at food

time,

with fine snow making through the walls of the worn tent and covering

our bags.

We are greatly cramped. Adams is suffering from cramp every now and

then. We

are eating our valuable food without marching. The wind has been

blowing eighty

to ninety miles an hour. We can hardly sleep. To-morrow I trust this

will be

over. Directly the wind drops we march as far south as possible, then

plant the

flag, and turn homeward. Our chief anxiety is lest our tracks may drift

up, for

to them we must trust mainly to find our depot; we have no land

bearings in

this great plain of snow. It is a serious risk that we have taken, but

we had

to play the game to the utmost, and Providence will look after us.  THE FARTHEST SOUTH CAMP AFTER SIXTY HOURS' BLIZZARD January 8.

Again all day in our bags, suffering considerably physically from cold

hands

and feet, and from hunger, but more mentally, for we cannot get on

south, and

we simply lie here shivering. Every now and then one of our party's

feet go,

and the unfortunate beggar has to take his leg out of the sleeping-bag

and have

his frozen foot nursed into life again by placing it inside the shirt,

against

the skin of his almost equally unfortunate neighbour. We must do

something more

to the south, even though the food is going, and we weaken lying in the

cold,

for with 72° of frost the wind cuts through our thin tent, and even the

drift

is finding its way in and on to our bags, which are wet enough as it

is. Cramp

is not uncommon every now and then, and the drift all round the tent

has made

it so small that there is hardly room for us at all. The wind has been

blowing

hard all day; some of the gusts must be over seventy or eighty miles an

hour.

This evening it seems as though it were going to ease down, and

directly it

does we shall be up and away south for a rush. I feel that this march

must be

our limit. We are so short of food, and at this high altitude, 11,600

ft., it

is hard to keep any warmth in our bodies between the scanty meals. We

have

nothing to read now, having depoted our little books to save weight,

and it is

dreary work lying in the tent with nothing to read, and too cold to

write much

in the diary. |