| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER X WINTER QUARTERS DURING POLAR NIGHT 1908: NOTES ON SPRING SLEDGING JOURNEYS The

meteorological screen had been

set up and observations begun before the Erebus party left. Now that

all hands

were back at the hut, a regular system of recording the observations

was

arranged. Adams, who was the meteorologist of the expedition, took all

the

observations from 8 A.M. to 8 P.M. The night-watchman took them from 10

P.M. to

6 A.M. These observations were taken every two hours, and it may

interest the

reader to learn what was done in this way, though I do not wish to

enter here

into a lengthy dissertation on meteorology. The observations on air

temperature, wind, and direction of cloud have an important bearing on

similar

observations taken in more temperate climes, and in a place like the

Antarctic,

where up till now our knowledge has been so meagre, it was most

essential that

every bit of information bearing on meteorological phenomena should be

noted.

We were in a peculiarly favourable position for observing not only the

changes

that took place in the lower atmosphere but also those which took place

in the

higher strata of the atmosphere. Erebus, with steam and smoke always

hanging above

it, indicated by the direction assumed by the cloud what the upper

air-currents

were doing, and thus we were in touch with an excellent high-level

observatory. The instruments under Adams' care were as complete as financial considerations had permitted. The meteorological screen contained a maximum thermometer, that is, a thermometer which indicates the highest temperature reached during the period elapsing between two observations. It is so constructed that when the mercury rises in the tube it remains at its highest point, though the temperature might fall greatly shortly afterwards. After reading the recorded height, the thermometer is shaken, and this operation causes the mercury to drop to the actual temperature obtaining at the moment of observation; the thermometer is then put back into the screen and is all ready for the next reading taken two hours later. A minimum thermometer registered the lowest temperature that occurred between the two-hourly readings, but this thermometer was not a mercury one, as mercury freezes at a temperature of about 39° below zero, and we therefore used spirit thermometers. When the temperature drops the surface of the column of spirit draws down a little black indicator immersed in it, and if the temperature rises and the spirit advances in consequence, the spirit flows past the indicator, which remains at the lowest point, and on the observations being taken its position is read on the graduated scale. By these instruments we were always able to ascertain what the highest temperature and what the lowest temperature had been throughout the two hours during which the observation screen had not been visited. In addition to the maximum and minimum thermometers, there were the wet and dry bulb thermometers. The dry bulb records the actual temperature of the air at the moment, and we used a spirit thermometer for this purpose. The wet bulb consisted of an ordinary thermometer, round the bulb of which was tied a little piece of muslin that had been dipped in water and of course froze at once on exposure to the air. The effect of the evaporation from the ice which covered the bulb was to cause the temperature recorded to be lower than that recorded by the dry-bulb thermometer in proportion to the amount of water present in the atmosphere at the time. To ensure accuracy the wet bulb thermometers were changed every two hours, the thermometer which was read being brought back to the hut and returned to the screen later freshly sheathed in ice. It was, of course, impossible to wet the exposed thermometer with a brush dipped in water, as is the practice in temperate climates, for water could not be carried from the hut. to the screen without freezing into solid ice. To check the thermometers there was also kept in the screen a self-recording thermometer, or thermograph. This is a delicate instrument fitted with metal discs, which expand or contract readily with every fluctuation of the temperature. Attached to these discs is a delicately poised lever carrying a pen charged with ink, and the point of this pen rests against a graduated roll of paper fastened to a drum, which is revolved by clockwork once in every seven days. The pen thus draws a line on the paper, rising and falling in sympathy with the changes in the temperature of the air.  THE "AURORA AUSTRALIS" In addition to

the meteorological

screen, there was another erection built on the top of the highest

ridge by

Mawson, who placed there an anemometer of his own construction to

register the

strength of the heaviest gusts of wind during a blizzard. We found that

the

squalls frequently blew with a force of over a hundred miles an hour.

There

remained still one more outdoor instrument connected with weather

observation,

that was the snow gauge. The Professor, by utilising some spare lengths

of

stove chimney, erected a snow gauge into which was collected the

falling snow

whenever a blizzard blew. The snow was afterwards taken into the hut in

the

vessel into which it had been deposited, and when it was melted down we

were

able to calculate fairly accurately the amount of the snowfall. This

observation was an important one, for much depends on the amount of

precipitation

in the Antarctic regions. It is on the precipitation in the form of

snow, and

on the rate of evaporation, that calculations regarding the formation

of the

huge snow-fields and glaciers depend. We secured our information

regarding the

rate of evaporation by suspending measured cubes of ice and snow from

rods

projecting at the side of the hut, where they were free from the

influence of

the interior warmth. Inside the hut was kept a standard mercurial

barometer,

which was also read every two hours, and in addition to this there was

a

barograph which registered the varying pressure of the atmosphere in a

curve

for a week at a time. Every Monday morning Adams changed the paper on

both

thermograph and barograph, and every day recorded the observations in

the meteorological

log. It will be seen that the meteorologist had plenty to occupy his

time, and

generally when the men came in from a walk they had some information to

record. As soon as the

ice was strong enough

to bear in the bay, Murray commenced his operations there. His object

was the

collection of the different marine creatures that rest on the bottom of

the sea

or creep about there, and he made extensive preparations for their

capture. A

hole was dug through the ice, and a trap let down to the bottom; this

trap was

baited with a piece of penguin or seal, and the shell-fish, crustacea,

and

other marine animals found their way in through the opening in the top,

and the

trap was usually left down for a couple of days. When it was hauled up,

the

contents were transferred to a tin containing water, and then taken to

the hut

and thawed out, for the contents always froze during the quarter of a

mile walk

homeward. As soon as the animals thawed out they were sorted into

bottles and

then killed by various chemicals, put into spirits and bottled up for

examination when they reached England. Later on Murray found that the

trap

business was not fruitful enough, so whenever a crack opened in the bay

ice, a

line was let down, one end being made fast at one end of the crack, and

the

length of the line allowed to sink in the water horizontally for a

distance of

sixty yards. A hole was dug at each end of the line and a small dredge

was let

down and pulled along the bottom, being hauled up through the hole at

the far

end. By this means much richer collections were made, and rarely did

the dredge

come up without some interesting specimens. When the crack froze over

again,

the work could still be continued so long as the ice was broken at each

end of

the line, and Priestley for a long time acted as Murray's assistant,

helping

him to open the holes and pull the dredge. When we took

our walks abroad, every

one kept his eyes open for any interesting specimen of rock or any

signs of

plant-life, and Murray was greatly pleased one day when we brought back

some

moss. This was found in a fairly sheltered spot beyond Back Door Bay

and was

the only specimen that we obtained in the neighbourhood of the winter

quarters

before the departure of the sun. Occasionally we came across a small

lichen and

some curious algae growing in the volcanic earth, but these measured

the extent

of the terrestrial vegetation in this latitude. In the north polar

regions, in

a corresponding latitude, there are eighteen different kinds of

flowering

plants, and there even exists a small stunted tree, a species of

willow. Although

terrestrial vegetation is

so scanty in the Antarctic, the same cannot be said of the sub-aqueous

plant-life. When we first arrived and some of us walked across the

north shore

of Cape Royds, we saw a great deal of open water in the lakes, and a

little

later, when all these lakes were frozen over, we walked across them,

and

looking down through the clear ice, could see masses of brilliantly

coloured

algae and fungi. The investigation of the plant-life in the lakes was

one of

the principal things undertaken by Murray, Priestley, and the Professor

during

the winter months. The reader has the plan of our winter quarters and

can

follow easily the various places that are mentioned in the course of

this

narrative.  A GROUP OF THE SHORE PARTY AT THE WINTER QUARTERS Standing (from left): Joyce, Day, Wild, ADams, Brocklehurst, Shackleton, Marshall, David, Armitage, Marston Sitting: Priestley, Murray, Roberts After

the

Erebus party returned, a

regular winter routine was arranged for the camp. Brocklehurst took no

part in

the duties at this time, for his frost-bitten foot prevented his moving

about,

and shortly after his return Marshall saw that it would be necessary to

amputate at least part of the big toe. The rest of the party all had a

certain

amount of work for the common weal, apart from their own scientific

duties.

From the time we arrived we always had a night-watchman, and we now

took turns

to carry out this important duty. Roberts was exempt from

night-watchman's

duties, as he was busy with the cooking all day, so for the greater

part of the

winter every thirteenth night each member took the night watch. The

ten-o'clock

observations was the night-watchman's first duty, and from that hour

till nine

o'clock next morning he was responsible for the wellbeing and care of

the hut,

ponies, and dogs. His most important duties were the two-hourly

meteorological

observations, the upkeep of the fire and the care of the acetylene

gas-plant.

The fire was kept going all through the night, and hot water was ready

for

making the breakfast when Roberts was called at 7.30 in the morning.

The night

watch was by no means an unpleasant duty, and gave each of us an

opportunity,

when his turn came round, of washing clothes, darning socks, writing

and doing

little odd jobs which could not receive much attention during the day.

The

night-watchman generally took his bath either once a fortnight or once

a month,

as his inclination prompted him. Some

individuals had a regular

programme which they adhered to strictly. For instance, one member,

directly

the rest of the staff had gone to bed, cleared the small table in front

of the

stove, spread a rug on it and settled down to a complicated game of

patience,

having first armed himself with a supply of coffee against the wiles of

the

drowsy god. After the regulation number of games had been played, the

despatch-box was opened, and letters, private papers and odds and ends

were

carefully inspected and replaced in their proper order, after which the

journal

was written up. These important matters over, a ponderous book on

historical

subjects received its share of attention. Socks were the

only articles of

clothing that had constantly to be repaired, and various were the

expedients

used to replace the heels, which, owing to the hard footgear, were

always

showing gaping holes. These holes had to be constantly covered, for we

were not

possessed of an unlimited number of any sort of clothes, and many and

varied

were the patches. Some men used thin leather, others canvas, and others

again a

sort of coarse flannel to sew on instead of darning the heels of the

socks.

Towards the end of the winter, the wardrobes of the various members of

the

expedition were in a very patched condition. During the

earlier months the

night-watchman was kept pretty busy, for the ponies took a long time to

get

used to the stable and often tried to break loose and upset things out

there

generally. These sudden noises took the watchman out frequently during

the

night, and it was a comfort to us when the animals at last learned to

keep

fairly quiet in their stable. The individual was fortunate who obtained

a good

bag of coal for his night watch, with plenty of lumps in it, for there

was then

no difficulty in keeping the temperature of the hut up to 40° Fahr.,

but a

great deal of our coal was very fine and caused much trouble during the

night.

To meet this difficulty we had recourse to lumps of seal blubber, the

watchman

generally laying in a stock for himself before his turn came for night

duty.

When placed on top of the hot coal the blubber burned fiercely, and it

was a

comfort to know that with the large supply of seals that could easily

be

obtained in these latitudes, no expedition need fear the lack of

emergency

fuel. There was no perceptible smell from the blubber in burning,

though fumes

same from the bit of hairy hide generally attached to it. The thickness

of the

blubber varied from two to four inches. Some watchmen during the night

felt

disinclined to do anything but read and take the observations, and I

was

amongst this number, for though I often made plans and resolutions as

to

washing and other necessary jobs, when the time came, these plans fell

through,

with the exception of the bath. Towards the

middle of winter some of

our party stayed up later than during the time when there was more work

outside, and there gradually grew into existence an institution known

as eleven

o'clock tea. The Professor was greatly attached to his sup of tea and

generally

undertook the work of making it for men who were still out of bed. Some

of us

preferred a cup of hot fresh milk, which was easily made from the

excellent

dried milk of which we had a large quantity. By one o'clock in the

morning,

however, nearly all the occupants of the hut were wrapped in deep and

more or

less noisy slumber. Some had a habit of talking in their sleep, and

their

fitful phrases were carefully treasured up by the night-watchman for

retailing

at the breakfast-table next morning; sometimes also the dreams of the

night

before were told by the dreamer to his own great enjoyment, if not to

that of

his audience. About five o'clock in the morning came the most trying

time for

the watchman. Then one's eyes grew heavy and leaden, and it took a deal

of effort

to prevent oneself from falling fast asleep. Some of us went in for

cooking

more or less elaborate meals. Marshall, who had been to a school of

cookery

before we left England, turned out some quite respectable bread and

cakes.

Though people jeered at the latter when placed on the table, one

noticed that

next day there were never any left. At 7.30 A.M. Roberts was called,

and the

watchman's night was nearly over. At this hour also Armytage or Mackay

was

called to look after the feeding of the ponies, but before mid-winter

day

Armytage had taken over the entire responsibility of the stables and

ponies,

and he was the only one to get up. At 8.30 A.M. all hands were called,

special

attention being paid to turning out the messman for the day, and after

some minutes

of luxurious half-wakefulness, people began to get up, expressing their

opinions forcibly if the temperature of the hut was below

freezing-point, and

informing the night-watchman of his affinity to Jonah if his report was

that it

was a windy morning. Dressing was for some of the men a very simple

affair,

consisting merely in putting on their boots and giving themselves a

shake; others,

who undressed entirely, got out of their pyjamas into their cold

underclothing.

At a quarter to nine the call came to let down the table from its

position near

the roof, and the messman then bundled the knives, forks and spoons on

to the

board, and at nine o'clock sharp every one sat down to breakfast. The

night-watchman's duties were

over for a fortnight, and the messman took on his work. The duties of

the

messmau were more onerous than those of the night-watchman. He began,

as I have

stated, by laying the table — a simple operation owing to the primitive

conditions under which we lived. He then garnished this with three or

four

sorts of hot sauces to tickle the tough palates of some of our party.

At nine

o'clock, when we sat down, the messman passed up the bowls of porridge

and the

big jug of hot milk, which was the standing dish every day. Little was

heard in

the way of conversation until this first course had been disposed of.

Then came

the order from the messman, " Up bowls," and reserving our spoons for

future use, the bowls were passed along. If it were a " fruit day,"

that is, a day when the second course consisted of bottled fruit, the

bowls

were retained for this popular dish. At twenty-five

minutes to ten

breakfast was over and we had had our smokes. All dishes were passed

up, the

table hoisted out of the way, and the messman started to wash up the

breakfast-things, assisted by his cubicle companion and by one or two

volunteers who would help him to dry up. Another of the party swept out

the hut;

and this operation was performed three times a day, so as to keep the

building

in a tidy state. After finishing the breakfast-things, the duty of the

man in

the house was to replenish the melting-pots with ice, empty the ashes

and tins

into the dust-box outside, and get in a bag of coal. By half-past ten

the

morning work was accomplished and the messman was free until twenty

minutes to

one, when he put the water on for the mid-day tea. At one o'clock tea

was

served and we had a sort of counter lunch. This was a movable feast,

for

scientific and other duties often made some of our party late, and

after it was

over there was nothing for the messman to do in the afternoon except to

have

sufficient water ready to provide tea at four o'clock. At a quarter

past six

the table was brought down again and dinner, the longest meal of the

day, was

served sharp at 6.30. One often heard the messman anxiously inquiring

what the

dinner dishes were going to consist of, the most popular from his point

of view

being those which resulted in the least amount of grease on the plates.

Dinner

was over soon after seven o'clock and then tea was served. Tobacco and

conversation kept us at table until 7.30, after which the same routine

of

washing up and sweeping out the hut was gone through. By 8.30 the

messman had

finished his duties for the day, and his turn did not come round again

for

another thirteen days. The state of the weather made the duties lighter

or

heavier, for if the day happened to be windy, the emptying of

dish-water and

ashes and the getting in of fresh ice was an unpleasant job. In a

blizzard it

was necessary to put on one's Burberries even to walk the few yards to

the

ice-box and back. In addition to

the standing jobs of

night-watchman and mess-man there were also special duties for various

members

of the expedition who had particular departments to look after. Adams

every

morning, directly after breakfast, wound up the chronometers and

chronometer

watches, and rated the instruments. He then attended to the

meteorological work

and took out his pony for exercise. If he were going far afield he

delegated

the readings to some members of the scientific staff who were generally

in the

vicinity of winter quarters. Marshall, as surgeon, attended to any

wounds, and

issued necessary pills, and then took out one of the ponies for

exercise. Wild,

who was storekeeper, was responsible for the issuing of all stores to

Roberts,

and had to open the cases_of tinned food and dig out of the snowdrifts

in which

it was buried the meat required for the day, either penguin, seal, or

mutton.

Joyce fed the dogs after breakfast, the puppies getting a dish of

scraps over

from our meals after breakfast and after dinner. When daylight returned

after

our long night, he worked at training the dogs to pull a sledge every

morning.

The Professor generally went off to " geologise " or to continue the

plane-table survey of our winter quarters, whilst Priestley and Murray

worked

on the floe dredging or else took the temperatures of the ice in shafts

which

the former had energetically sunk in the various lakes around us.

Mawson was

occupied with his physical work, which included auroral observations

and the

study of the structure of the ice, the determination of atmospheric

electricity

and many other things. In fact, we were all busy, and there was little

cause

for us to find the time hang heavy on our hands; the winter months sped

by and

this without our having to sleep through them, as has often been done

before by

polar expeditions. This was due to the fact that we were only a small

party and

that our household duties, added to our scientific work, fully occupied

our

time.  THE TYPE-CASE AND PRINTING PRESS FOR THE PRODUCTION OF THE "AURORA AUSTRALIS" IN JOYCE'S AND WILD'S CUBICLE, KNOWN AS "THE ROGUES' RETREAT" It would only

be repetition to

chronicle our doings from day to day during the months that elapsed

from the

disappearance of the sun until the time arrived when the welcome

daylight came

back to us. We lived under conditions of steady routine, affected only

by short

spells of bad weather, and found amply sufficient to occupy ourselves

in our

daily work, so that the spectre known as " polar ennui " never made

its appearance. Mid-winter's day and birthdays were the occasions of

festivals,

when our teetotal regime was broken through and a sort of mild spree

indulged

in. Before the sun finally went hockey and football were the outdoor

games,

while indoors at night some of us played bridge, poker, and dominoes.

Joyce,

Wild, Marston, and Day during the winter months spent much time in the

production

of the "Aurora Australia," the first book ever written, printed,

illustrated, and bound in the Antarctic. Through the generosity of

Messrs.

Joseph Causton and Sons, Limited, we had been provided with a complete

printing

outfit and the necessary paper for the book, and Joyce and Wild had

been given

instruction in the art of type-setting and printing, Marston being

taught

etching and lithography. They had hardly become skilled craftsmen, but

they had

gained a good working knowledge of the branches of the business. When

we had

settled down in the winter quarters, Joyce and Wild set up the little

hand-press and sorted out the type, these preliminary operations taking

up all

their spare time for some days, and then they started to set and print

the

various contributions that were sent in by members of the expedition.

The early

days of the printing department were not exactly happy, for the two

amateur

typesetters found themselves making many mistakes, and when they had at

last

"set up" a page, made all the necessary corrections, and printed off

the required number of copies, they had to undertake the laborious work

of

"dissing," that is, of distributing the type again. They plodded

ahead steadily, however, and soon became more skilful, until at the end

of a

fortnight or three weeks they could print two pages in a day. A lamp

had to be

placed under the type-rack to keep it warm, and a lighted candle was

put under

the inking-plate, so that the ink would keep reasonably thin in

consistency.

The great trouble experienced by the printers at first was in securing

the

right pressure on the printing-plate and even inking of the page, but

experience showed them where they had been at fault. Day meanwhile

prepared the

binding by cleaning, planing, and polishing wood taken from the Venesta

cases-in which our provisions were packed. Marston reproduced the

illustrations

by algraphy, or printing from aluminium plates. He had not got a proper

lithographing press, so had to use an ordinary etching press, and he

was

handicapped by the fact that all our water had a trace of salt in it.

This

mineral acted on the sensitive plates, but Marston managed to produce

what we

all regarded as creditable pictures. In its final form the book had

about one

hundred and twenty pages, and it had at least assisted materially to

guard us

from the danger of lack of occupation during the polar night. On March 13 we

experienced a very

fierce blizzard. The hut shook and rocked in spite of our sheltered

position,

and articles that we had left lying loose outside were scattered far

and wide.

Even cases weighing from fifty to eighty pounds were shifted from where

they

had been resting, showing the enormous velocity of the wind. When the

gale was

over we put everything that was likely to blow away into positions of

greater

safety. It was on this day also that Murray found living microscopical

animals

on some fungus that had been thawed out from a lump of ice taken from

the

bottom of one of the lakes. This was one of the most interesting

biological

discoveries that had been made in the Antarctic, for the study of these

minute

creatures occupied our biologist for a great part of his stay in the

south, and

threw a new light on the capability of life to exist under conditions

of

extreme cold and in the face of great variations of temperature. We all

became

vastly interested in the rotifers during our stay, and the work of the

biologist in this respect was watched with keen attention. From our

point of

view there was an element of humour in the endeavours of Murray to slay

the

little animals he had found. He used to thaw them out from a block of

ice,

freeze them up again, and repeat this process several times without

producing

any result as far as the rotifers were concerned. Then he tested them

in brine

so strongly saline that it would not freeze at a temperature above

minus 7°

Fahr., and still the animals lived. A good proportion of them survived

a

temperature of 200° Fahr. It became a contest between rotifers and

scientist,

and generally the rotifers seemed to triumph. At the end of

March there was still

open water in the bay and we observed a killer whale chasing a seal.

About this

time we commenced digging a trench in Clear Lake and obtained, when we

came to

water, samples of the bottom mud and fungus, which was simply swarming

with

living organisms. The sunsets at the beginning of April were wonderful;

arches

of prismatic colours, crimson and golden-tinged clouds, hung in the

heavens

nearly all day, for time was going on and soon the sun would have

deserted us.

The days grew shorter and shorter, and the twilight longer. During

these

sunsets the western mountains stood out gloriously and the summit of

Erebus was

wrapped in crimson when the lower slopes had faded into grey. To Erebus

and the

western mountains our eyes turned when the end of the long night grew

near in

the month of August, for the mighty peaks are the first to catch up and

tell

the tale of the coming glory and the last to drop the crimson mantle

from their

high shoulders as night draws on. Tongue and pencil would sadly fail in

attempting to describe the magic of the colouring in the days when the

sun was

leaving us. The very clouds at this time were iridescent with rainbow

hues. The

sunsets were poems. The change from twilight into night, sometimes lit

by a

crescent moon, was extraordinarily beautiful, for the white cliffs gave

no part

of their colour away, and the rocks beside them did not part with their

blackness, so the effect of deepening night over these contrasts was

singularly

weird. In my diary I noted that throughout April hardly a day passed

without an

auroral display. On more than one occasion the auroral showed distinct

lines of

colour, merging from a deep red at the base of the line of light into a

greenish hue on top. About the beginning of April the temperature began

to drop

considerably, and for some days in calm, still weather the thermometer

often

registered 40° below zero. On April 6,

Marshall decided that it

was necessary to amputate Brocklehurat's big toe, as there was no sign

of it

recovering like the other toes from the frost-bite he had received on

the

Erebus journey. The patient was put under chloroform and the operation

was

witnessed by an interested and sympathetic audience. After the bone had

been

removed, the sufferer was shifted into my room, where he remained till

just

before Midwinter's Day, when he was able to get out and move about

again. We

had about April 8 one of the peculiar southerly blizzards so common

during our

last expedition, the temperature varying rapidly from minus 23° to plus

4°

Fahr. This blizzard continued till the evening of the 11th, and when it

had

abated we found the bay and sound clear of ice again. I began to feel

rather

worried about this and wished for it to freeze over, for across the ice

lay our

road to the south. We observed occasionally about this time that

peculiar phenomenon

of McMurdo Sound called "earth shadows." Long dark bars, projected up

into the sky from the western mountains, made their appears nee at

sunrise.

These lines are due to the shadow of the giant Erebus being cast across

the

western mountains. Our days were now getting very short and the amount

of

daylight was a negligible quantity. We boarded up the remainder of the

windows,

and depended entirely upon the artificial light in the winter quarters.

The

light given by the acetylene gas was brilliant, the four burners

lighting the

whole of the hut. When daylight

returned and sledging

began about the middle of August, on one of our excursions on the Cape

Royds

peninsula, we found growing under volcanic earth a large quantity of

fungus.

This was of great interest to Murray, as plant-life of any sort is

extremely

rare in the Antarctic. Shortly after this a strong blizzard cast up a

quantity

of seaweed on our ice-foot; this was another piece of good fortune, for

on the

last expedition we obtained very little seaweed. When

Midwinter's Day had passed and

the twilight, that presaged the return of the sun began to be more

marked day

by day, I set on foot the arrangements for the sledging work in the

forthcoming

spring. It was desirable that, at as early a date as possible, we

should place

a depot of stores at a point to the south, in preparation for the

departure of

the Southern Party, which was to march towards the Pole. I hoped to

make this

depot at least one hundred miles from the winter quarters. Then it was

desirable

that we should secure some definite information regarding the condition

of the

snow surface on the Barrier, and I was also anxious to afford the

various

members of the expe- dition some practice in sledging before the

serious work

commenced. Some of us had been in the Antarctic before, but the

majority of the

men had not yet had any experience of marching and camping on snow and

ice, in

low temperatures.  THE AUTUMN SUNSET During the

winter I had given a

great deal of earnest consideration to the question of the date at

which the

party that was to march towards the Pole should start from the hut. The

goal

that we hoped to attain lay over 880 statute miles to the south, and

the brief

summer was all too short a time in which to march so far into the

unknown and

return to winter quarters. The ship would have to leave for the north

about the

end of February, for the ice would then be closing in, and, moreover,

we could

not hope to carry on our sledges much more than a three months' supply

of

provisions, on anything like full rations. I finally decided that the

Southern

Party should leave the winter quarters about October 28, for if we

started

earlier it was probable that the ponies would suffer from the severe

cold at nights,

and we . would gain no advantage from getting away early in the season

if, as a

result, the ponies were incapacitated before we had made much progress.

The date for

the departure of the

Southern Party having been fixed, it became necessary to arrange for

the laying

of the depot during the early spring, and I thought that the first step

towards

this should be a preliminary journey on the Barrier surface, in order

to gain

an idea of the conditions that would be met with, and to ascertain

whether the

motor-car would be of service, at any rate for the early portion of the

journey. The sun had not yet returned and the temperature was very low

indeed,

but we had proved in the course of the Discovery

expedition that it is quite possible to travel under these conditions.

I

therefore started on this preliminary journey on August 12, taking with

me

Professor David, who was to lead the Northern Party towards the South

Magnetic

Pole, and Bertram Armytage, who was to take charge of the party that

was to

make a journey into the mountains of the west later in the year. The

reader can

imagine that it was not with feelings of unalloyed pleasure that we

turned our

backs on the warm, well-found hut and faced our little journey out into

the

semi-darkness and intense cold, but we did get a certain amount of

satisfaction

from the thought that at last we were actually beginning the work we

had come

south to undertake. We were

equipped for a fortnight

with provisions and camp gear, packed on one sledge, and had three

gallons of

petroleum in case we should decide to stay out longer. A gallon of oil

will

last a party of three men for about ten days under ordinary conditions,

and we

could get more food at Hut Point if we required it. We took three

one-man

sleeping-bags, believing that they would be sufficiently warm in spite

of the

low temperature. The larger bags, holding two or three men, certainly

give

greater warmth, for the occupants warm one another, but, on the other

hand,

one's rest is very likely to be disturbed by the movements of a

companion. We

were heavily clothed for this trip, because the sun would not rise

above the

horizon until another ten days had passed. Our comrades

turned out to see us

off, and the pony Quan pulled the sledge with our camp gear over the

sea ice

until we got close to the glacier south of Cape Barne, about five miles

from

the winter quarters. Then he was sent back, for the weather was growing

thick,

and, as already explained, I did not want to run any risk of losing

another

pony from our sadly diminished team. We proceeded close in by the

skuary, and a

little further on pitched camp for lunch. Professor David, whose thirst

for

knowledge could not be quenched, immediately went off to investigate

the

geology of the neighbourhood. After lunch we started to pull our sledge

round

the coast towards Hut Point, but the weather became worse, making

progress

difficult, and at 6 P.M. we camped close to the tide-crack at the south

side of

Turk's Head. We slept well and soundly, although the temperature was

about

forty degrees below zero, and the experience made me more than ever

convinced

of the superiority of one-man sleeping-bags. On the

following morning, August 13,

we marched across to Glacier Tongue, having to cross a wide crack that

had been

ridged up by ice-pressure betweem Tent Island and the Tongue. As soon

as we had

crossed we saw the depot standing up clear against the sky-line on the

Tongue.

This was the depot that had been made by the ship soon after our first

arrival

in the sound. We found no difficulty in getting on to the Tongue, for a

fairly

gentle slope led up from the sea-ice to the glacier surface. The snow

had blown

over from the south during the winter and made a good way. We found the

depot

intact, though the cases, lying on the ice, had been bleached to a

light yellow

colour by the wind and sun. We had lunch on the south side of the

Tongue, and

found there another good way down to the sea ice. There is a very

awkward crack

on the south side, but this can hardly be called a tide-crack. I think

it is

due to the fact that the tide has more effect on the sea ice than on

the heavy

mass of the Tongue, though there is no doubt this also is afloat; the

rise and

fall of the two sections of ice are not coincident, and a crack is

produced.

The unaccustomed pulling made us tired, and we decided to pitch a camp

about

four miles off Hut Point, before reaching Castle Rock. Castle Rock is

distant

three miles and a half from Hut Point, and we had always noticed that

after we

got abeam of the rock the final march on to the hut seemed very long,

for we

were always weary by that time.  PREPARING A SLEDGE DURING THE WINTER We climbed to

the top of Crater Hill

with a collecting-bag and the Professor's camera, and here we took some

photographs and made an examination of the cone. Professor David

expressed the

opinion that the ice-sheet had certainly passed over this hill, which

is about

1100 ft. high, for there was distinct evidence of glaciation. We

climbed along

the ridge to Castle Rock, about four miles to the north, and made an

examination of the formation there. Then wtS returned to the hut to

have a

square meal and get ready for our journey across the Barrier. The old hut had

never been a very

cheerful place, even when we were camped alongside it in the Discovery, and it looked doubly

inhospitable now, after having stood empty and neglected for six years.

One

side was filled with cases of biscuit and tinned meat, and the snow

that had

found its way in was lying in great piles around the walls. There was

no stove,

for this had been taken away with the Discovery,

and coal was scattered about the floor with other debris and rubbish.

Besides

the biscuits and the tinned beef and mutton there was some tea and

coffee

stored in the hut. We cleared a spot on which to sleep, and decided

that we

would use the cases of biscuit and meat to build another hut inside the

main

one, so that the quarters would be a little more cosy. I proposed to

use this

hut as a stores depot in connection with the southern journey, for if

the ice

broke out in the Sound unexpectedly early, it would be difficult to

convey

provisions from Cape Royds to the Barrier, and, moreover, Hut Point was

twenty

miles further south than our winter quarters. We spent that night on

the floor

of the hut, and slept fairly comfortably, though not as well as on the

previous

night in the tent, because we were not so close to one another. On the morning

of the following day

(August 15) we started away about 9 A.M., crossed the smooth ice to

Winter

Harbour, and passed close round Cape Armitage. We there found cracks

and

pressed-up ice, showing that there had been Barrier movement, and about

three

miles further on we crossed the spot at which the sea ice joins the

Barrier,

ascending a slope about eight feet high. Directly we got on to the

Barrier ice

we noticed undulations on the surface. We pushed along and got to a

distance of

about twelve miles from Hut Point in eight hours. The surface generally

was

hard, but there were very marked sastrugi, and at times patches of soft

snow.

The conditions did not seem favourable for the use of the motor-car

because we

had already found that the machine could not go through soft snow for

more than

a few yards, and I foresaw that if we brought it out on to the Barrier

it would

not be able to do much in the soft surface that would have to be

traversed. The

condition of the surface varied from mile to mile, and it would be

impracticable to keep changing the wheels of the car in order to meet

the

requirements of each new surface. The temperature

was very low,

although the weather was fine. At 6 P.M. the thermometer showed

fifty-six

degrees below zero, and the petroleum used for the lamp had become

milky in

colour and of a creamy consistency. That night the temperature fell

lower

still, and the moisture in our sleeping-bags, from our breath and

Burberries,

made us very uncomfortable wheb the bags had thawed out with the warmth

of our

bodies. Everything we touched was appallingly cold, and we got no sleep

at all.

The next morning (August 16) the weather was threatening, and there

were

indications of the approach of a blizzard, and I therefore decided to

march

back to Hut Point, for there was no good purpose to be served by taking

unnecessary risks at that stage of the expedition. We had some warm

food, of

which we stood sorely in need after the severe night, and then started

at 8 A.M.

to return to Hut Point. By hard marching, which had the additional

advantage of

warming us up, we reached the old hut again at three o'clock that

afternoon,

and we were highly delighted to get into its shelter. The sun had not

yet

returned, and though there was a strong light in the sky during the

day, the

Barrier was not friendly under winter conditions. We reached the

hut none too soon,

for a blizzard sprang up, and for some days we had to remain in

shelter. We

utilised the time by clearing up the portion of the hut that we

proposed to

use, even sweeping it with an old broom we found, and building a

shelter of the

packing-cases, piling them right up to the roof round a space about

twenty feet

by ten; and thus we made comparatively cosy quarters. We rigged a table

for the

cooking-gear, and put everything neatly in order. My two companions

were, at

this time, having their first experience of polar life under marching

conditions as far as equipment was concerned, and they were gaining

knowledge

that proved very useful to them on the later journeys. On the morning

of August 22, the day

on which the sun once more appeared above the horizon, we started back

for the

winter quarters, leaving Hut Point at 5 A.M. in the face of a bitterly

cold

wind from the north-east, with low drift. We marched without a stop for

nine

miles, until we reached Glacier Tongue, and then had an early lunch. An

afternoon march of fourteen miles took us to the winter quarters at

Cape Royds,

where we arrived at 5 P.M. We were not expected at the hut, for the

weather was

thick and windy, but our comrades were delighted to see us, and we had

a hearty

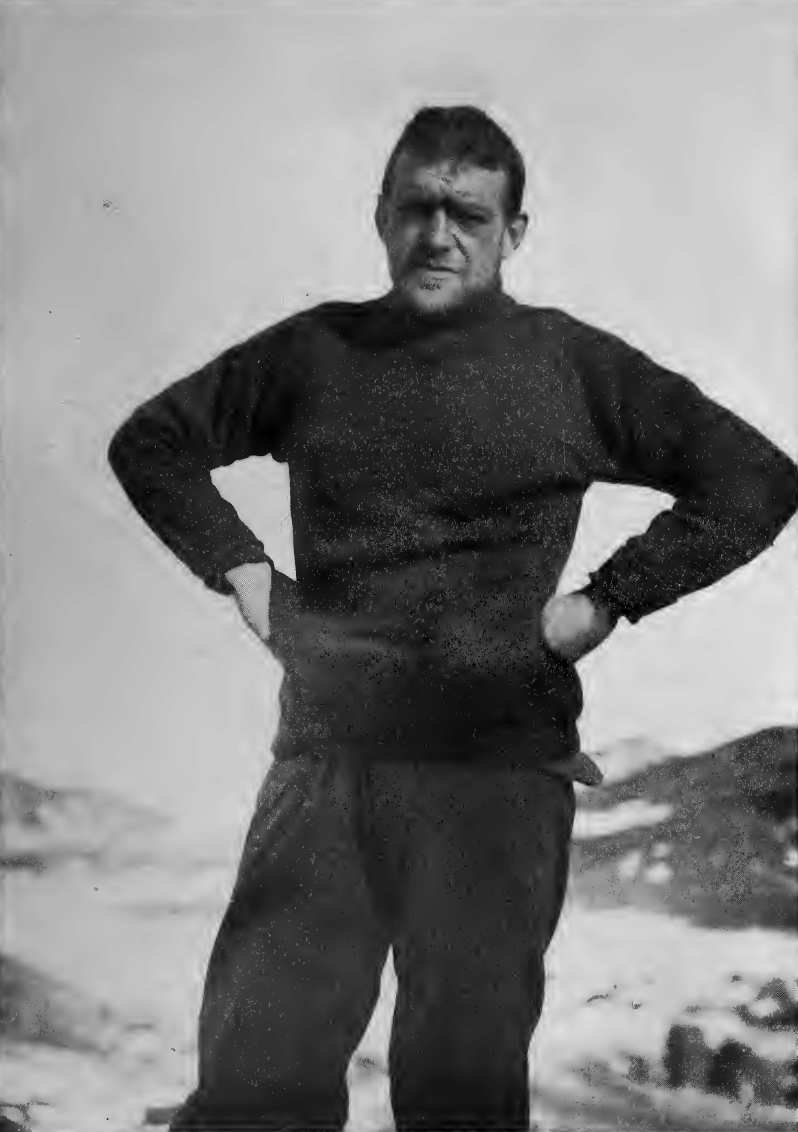

dinner and enjoyed the luxury of a good bath.  THE LEADER OF THE EXPEDITION IN WINTER GARB On September 1,

Wild, Day, and

Priestley started for Hut Point via Glacier Tongue with 450 lb. of gear

and

provisions, their instructions being to leave 230 lb. of provisions at

the Discovery hut in readiness for

the

southern journey. They made a start at 10.20 A.M., being accompanied by

Brocklehurst with a pony for the first five miles. The weather was

fine, but a

very low barometer gave an indication that bad weather was coming. I

did not

hesitate to let these parties face bad weather, because the road they

were to

travel was well known, and a rough experience would be very useful to

the men

later in the expedition's work. The party camped in the snow close to

the south

side of Glacier Tongue. Next morning

(September 2) the

weather was still bad, and they were not able to make a start until

after noon.

At 1.20 P.M. they ran out of the northerly wind into light southerly

airs with

intervals of calm, and they noticed that at the meeting of the two

winds the

clouds of drift were formed into whirling columns, some of them over

forty feet

high. They reached the Discovery

hut

at 4.30 P.M., and soon turned in, the temperature being forty degrees

below

zero. When they dressed at 5.30 A.M. (September 3) they found that a

southerly

wind with heavy drift rendered a start on the return journey

inadvisable. After

breakfast they walked over to Observation Hill, where they examined a

set of

stakes which Ferrar and Wild had placed in the Gap glacier in 1902. The

stakes

showed that the movement of the glacier during the six years since the

stakes

had been put mto position had amounted to a few inches only. The middle

stake

had advanced eight inches and those next it on either side about six

inches. At

noon the wind dropped, and although the drift was still thick, the

party

started back, steering by the sastrugi till the Tongue was reached.

They camped

for the night in the lee of the glacier, with a blizzard blowing over

them and

the temperature rising, the result being that everything was

uncomfortably wet.

They managed to sleep, however, and when they awoke the next morning

the

weather was clear, and they had an easy march in, being met beyond Cape

Barne

by Joyce, Brocklehurst, and the dogs. They had been absent four days. Each party came

back with adventures

to relate, experiences to compare, and its own views on various matters

of

detail connected with sledge-travelling. Curiously enough, every one of

the

parties encountered bad weather, but there were no accidents, and all

the men

seemed to enjoy the work. Early in September a party consisting of Adams, Marshall, and myself started for Hut Point, and we decided to make one march of the twenty-three miles, and not camp on the way. We started at 8 A.M., and when we were nearly at the end of the journey, and were struggling slowly through bad snow towards the hut, close to the end of Hut Point, a strong blizzard came up. Fortunately I knew the bearings of the hut, and how to get over the ice-foot. We abandoned the extra weights we were pulling for the depot, and managed to get to the hut at 10 P.M. in a sorely frost-bitten condition, almost too tired to move. We were able to get ourselves some hot food, however, and were soon all right again. I mention the incident merely to show how constantly one has to be on guard against the onslaughts of the elements in the inhospitable regions of the south. |