| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

|

THE EXPEDITION Inception and

Preparation: Food-supply: Equipment: The Nimrod:

Hut for Winter Quarters:

Clothing: Ponies, Dogs, and Motor-car: Scientific Instruments:

Miscellaneous

Articles of Equipment MEN go out into

the void spaces of

the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by a love of

adventure,

some have the keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again

are drawn

away from the trodden paths by the "lure of little voices," the

mysterious fascination of the unknown. I think that in my own case it

was a

combination of these factors that determined me to try my fortune once

again in

the frozen south. I had been invalided home before the conclusion of

the Discovery expedition, and I had

a very

keen desire to see more of the vast continent that lies amid the

Antarctic

snows and glaciers. Indeed the stark polar lands grip the hearts of the

men who

have lived on them in a manner that can hardly be understood by the

people who

have never got outside the pale of civilisation. I was convinced,

moreover,

that an expedition on the lines I had in view could justify itself by

the

results of its scientific work. The Discovery

expedition had brought back a great store of information, and had

performed

splendid service in several important branches of science. I believed

that a

second expedition could carry the work still further. The Discovery

expedition had gained knowledge

of the great chain of

mountains running in a north and south direction from Cape Adare to

latitude

82° 17' South, but whether this range turned to the south-east or

eastward for

any considerable distance was not known, and therefore the southern

limits of

the Great Ice Barrier plain had not been defined. The glimpses gained

of King

Edward VII Land from the deck of the Discovery

had not enabled us to determine either its nature or its extent, and

the

mystery of the Barrier remained unsolved. It was a matter of importance

to the

scientific world that information should be gained regarding the

movement of

the ice-sheet that forms the Barrier. Then I wanted to find out what

lay beyond

the mountains to the south of latitude 82° 17' and whether the

Antarctic

continent rose to a plateau similar to the one found by Captain Scott

beyond

the western mountains. There was much to be done in the field of

meteorology,

and this work was of particular importance to Australia and New

Zealand, for

these countries are affected by weather conditions that have their

origin in

the Antarctic. Antarctic zoology, though somewhat limited, as regarded

the

range of species, had very interesting aspects, and I wanted to devote

some

attention to mineralogy, apart from general geology. The aurora

australis,

atmospheric electricity, tidal movements, hydrography, currents of the

air, ice

formations and movements, biology and geology, offered an unlimited

field for

research, and the despatch of an expedition seemed to be justified on

scientific grounds quite apart from the desire to gain a high latitude.

The difficulty

that confronts most

men who wish to undertake exploration work is that of finance, and in

this

respect I was rather more than ordinarily handicapped. The equipment

and

despatch of an Antarctic expedition means the expenditure of very many

thousands of pounds, without the prospect of any speedy return, and

with a

reasonable probability of no return at all. I drew up my scheme on the

most

economical lines, as regarded both ship and staff, but for over a year

I tried

vainly to raise sufficient money to enable me to make a start. I

secured

introductions to wealthy men, and urged to the best of my ability the

importance of the work I proposed to undertake, but the money was not

forthcoming, and it almost seemed as though I should have to abandon

the

venture altogether. I persisted, and towards the end of 1906 I was

encouraged

by promises of support from one or two personal friends. Then I made a

fresh

effort, and on February 12, 1907, I had enough money promised to enable

me to

announce definitely that I would go south with an expedition. As a

matter of fact,

some of the promises of support made to me could not be fulfilled, and

I was

faced by financial difficulties for some time; but when the Governments

of

Australia and New Zealand came to my assistance, the position became

more

satisfactory. In the

Geographical Journal for

March 1907 I outlined my plan of campaign, but this had to be changed

in

several respects at a later date owing to the exigencies of

circumstances. My

intention was that the expedition should leave New Zealand at the

beginning of

1908, and proceed to winter quarters on the Antarctic continent, the

ship to

land the men and stores and then return. By avoiding having the ship

frozen in,

I would render the use of a relief ship unnecessary, as the same vessel

could

come south again the following summer and take us off. "The shore-party

of

nine or twelve men will winter with sufficient equipment to enable

three

separate parties to start out in the spring," I announced. "One party

will go east, and, if possible, across the Barrier to the new land

known as

King Edward VII Land, follow the coast-line there south, if the coast

trends

south, or north if north, returning when it is considered necessary to

do so.

The second party will proceed south over the same route as that of the

southern

sledge-party of the Discovery; this

party will keep from fifteen to twenty miles from the coast, so as to

avoid any

rough ice. The third party will possibly proceed westward over the

mountains,

and, instead of crossing in a line due west, will strike towards the

magnetic

pole. The main changes in equipment will be that Siberian ponies will

be taken

for the sledge journeys both east and south, and also a specially

designed

motor-car for the southern journey. . . . I do not intend to sacrifice

the

scientific utility of the expedition to a mere record-breaking journey,

but say

frankly, all the same, that one of my great efforts will be to reach

the

southern geographical pole. I shall in no way neglect to continue the

biological, meteorological, geological and magnetic work of the Discovery." I added that I would

endeavour to sail along the coast of Wilkes Land, and secure definite

information regarding that coast-line. The programme

was an ambitious one

for a small expedition, no doubt, but I was confident, and I think I

may claim

that in some measure my confidence has been justified. Before we

finally left

England, I had decided that if possible I would establish my base on

King

Edward VII Land instead of at the Discovery

winter quarters in McMurdo Sound, so that we might break entirely new

ground.

The narrative will show how completely, as far as this particular

matter was

concerned, all my plans were upset by the demands of the situation. The

journey

to King Edward VII Land over the Barrier was not attempted, owing

largely to

the unexpected loss of ponies before the winter. I laid all my plans

very

carefully, basing them on experience I had gained with the Discovery

expedition, and in the fitting

out of the relief ships

Terra Nova and Morning, and the Argentine expedition that went to the

relief of

the Swedes. I decided that I would have no committee, as the expedition

was

entirely my own venture, and I wished to supervise personally all the

arrangements. When I found

that some promises of

support had failed me and had learned that the Royal Geographical

Society,

though sympathetic in its attitude, could not see its way to assist

financially,

I approached several gentlemen and suggested that they should guarantee

me at

the bank, the guarantees to be redeemed by me in 1910, after the return

of the

expedition. It was on this basis that I secured a sum of £20,000, the

greater

part of the money necessary for the starting of the expedition, and I

cannot

express too warmly my appreciation of the faith shown in me and my

plans by the

men who gave these guarantees, which could be redeemed only by the

proceeds of

lectures and the sale of this book after the expedition had concluded

its work.

These preliminary matters settled, I started to buy stores and

equipment, to

negotiate for a ship, and to collect round me the men who would form

the

expedition. The equipping

of a polar expedition

is a task demanding experience as well as the greatest attention to

points of

detail. When the expedition has left civilisation, there is no

opportunity to

repair any omission or to secure any article that may have been

forgotten. It

is true that the explorer is expected to be a handy man, able to

contrive

dexterously with what materials he may have at hand; but makeshift

appliances

mean increased difficulty and added danger. The aim of one who

undertakes to

organise such an expedition must be to provide for every contingency,

and in

dealing with this work I was fortunate in being able to secure the

assistance

of Mr. Alfred Reid, who had already gained considerable experience in

connection with previous polar ventures. I appointed Mr. Reid manager

of the

expedition, and I found him an invaluable assistant. I was fortunate,

too, in

not being hampered by committees of any sort. I kept the control of all

the

arrangements in my own hands, and thus avoided the delays that are

inevitable

when a group of men have to arrive at a decision on points of detail. The first step

was to secure an

office in London, and we selected a furnished room at 9 Regent Street,

as the

headquarters of the expedition. The staff at this period consisted of

Mr. Reid,

a district messenger and myself, but there was a typewriting office on

the same

floor, and the correspondence, which grew in bulk day by day, could be

dealt

with as rapidly as though I had employed stenographers and typists of

my own. I

had secured estimates of the cost of provisioning and equipping the

expedition

before I made any public announcement regarding my intentions, so that

there

were no delays when once active work had commenced. This was not an

occasion

for inviting tenders, because it was vitally important that we should

have the

best of everything, whether in food or gear, and I therefore selected,

in

consultation with Mr. Reid, the firms that should be asked to supply

us. Then

we proceeded to interview the heads of these firms, and we found that

in nearly

every instance we were met with generous treatment as to prices, and

with ready

cooperation in regard to details of manufacture and packing. FOOD

-SUPPLIES Several very

important points have

to be kept in view in selecting the food-supplies for a polar

expedition. In

the first place the food must be wholesome and nourishing in the

highest degree

possible. At one time that dread disease scurvy used to be regarded as

the

inevitable result of a prolonged stay in the ice-bound regions, and

even the Discovery expedition,

during its labours

in the Antarctic in the years 1902-4, suffered from this complaint,

which is

often produced by eating preserved food that is not in a perfectly

wholesome

condition. It is now recognised that scurvy may be avoided if the

closest

attention is given to the preparation and selection of food-stuffs on

scientific lines, and I may say at once that our efforts in this

direction were

successful, for during the whole course of the expedition we had not

one case

of sickness attributable directly or indirectly to the foods we had

brought

with us. Indeed, beyond a few colds, apparently due to germs from a

bale of

blankets, we experienced no sickness at all at the winter quarters. In the second

place the food taken

for use on the sledging expeditions must be as light as possible,

remembering

always that extreme concentration renders the food less easy of

assimilation and

therefore less healthful. Extracts that may be suitable enough for use

in

ordinary climates are of little use in the polar regions, because under

conditions of very low temperature the heat of the body can be

maintained only

by use of fatty and farinaceous foods in fairly large quantities. Then

the

sledging-foods must be such as do not require prolonged cooking, that

is to

say, it must be sufficient to bring them to the boiling-point, for the

amount

of fuel that can be carried is limited. It must be possible to eat the

foods without

cooking at all, for the fuel may be lost or become exhausted. More latitude

is possible in the

selection of foods to be used at the winter quarters of the expedition,

for the

ship may be expected to reach that point, and weight is therefore of

less importance.

My aim was to secure a large variety of foods for use during the winter

night.

The long months of dark' ness impose a severe strain on any men

unaccustomed to

the conditions, and 'it is desirable to relieve the monotony in every

way

possible. A variety of food is healthful, moreover, and this is

especially

important at a period when it is difficult for the men to take much

exercise,

and when sometimes they are practically confined to the hut for days

together

by bad weather. All these

points were taken into

consideration in the selection of our food-stuffs. I based my estimates

on the

requirements of twelve men for two years, but this was added to in New

Zealand

when I increased the staff. Some important articles of food were

presented to

the expedition by the manufacturers: and others, such as the biscuits

and

pemmican, were specially manufactured to my order. The question of

packing

presented some difficulties, and I finally decided to use "Venesta"

cases for the food-stuffs and as much as possible of the equipment.

These cases

are manufactured from composite boards prepared by uniting three layers

of

birch or other hard wood with waterproof cement. They are light,

weather-proof,

and strong, and proved to be eminently suited to our purposes. The

cases I

ordered measured about two feet six inches by fifteen inches, and we

used some

2500 of them. The saving of weight, as compared with an ordinary

packing-case,

was about four pounds per case, and we had no trouble at all with

breakages, in

spite of the rough handling given our stores in the process of landing

at Cape

Royds after the expedition had reached the Antarotio regions. I decided to

take food-supplies for

the shore-party for two years; and some additions were made after the

arrival

of the Nimrod in New Zealand. I arranged that

supplies for

thirty-eight men for one year should be carried by the Nimrod

when the vessel went south for the second time to bring back

the shore-party. This was a precautionary measure in case the Nimrod should get caught in the ice and

be compelled to spend a winter in the Antarctic, in which case we would

still

have had one year's provisions in hand. EQUIPMENT After placing

some of the principal

orders for food-supplies I went to Norway with Mr. Reid in order to

secure the

sledges, fur boots and mits, sleeping-bags, ski, and some other

articles of

equipment. I was fortunate, on the voyage from Hull to Christiania, in

making

the acquaintance of Captain Pepper, the commodore captain of the Wilson

Line of

steamers. He took a keen interest in the expedition, and he was of very

great

assistance to me in the months that followed, for he undertook to

inspect the

sledges in the process of manufacture. He was at Christiania once in

each

fortnight, and he personally looked to the lashings and seizings as

only a

sailor could. We arrived at Christiania on April 22, and then learned

that Mr.

C. S. Christiansen, the maker of the sledges used on the Discovery

expedition, was in the United States. This was a

disappointment, but after consultation with Scott-Hansen, who was the

first

lieutenant of the Frain on Nansen's famous expedition, I decided to

place the

work in the hands of Messrs. L. H. Hagen and Company. The sledges were

to be of

the Nansen pattern, built of specially selected timber, and of the best

possible workmanship. I ordered ten twelve-foot sledges, eighteen

eleven-foot

sledges and two seven-foot sledges. The largest ones would be suitable

for

pony-haulage. The eleven-foot ones could be drawn by either ponies or

men, and the

small pattern would be useful for work around the winter quarters and

for short

journeys such as the scientists of the expedition were likely to

undertake. The

timbers used for the sledges were seasoned ash and American hickory,

and in

addition to Captain Pepper, Captain Isaachsen and Lieutenant

Scott-Hansen, both

experienced Arctic explorers, watched the work of construction on my

behalf.

Their interest was particularly valuable to me, for they were able in

many

little ways hardly to be understood by the lay reader to ensure

increased

strength and efficiency. I had formed the opinion that an eleven-foot

sledge

was best for general work, for it was not so long as to be unwieldy,

and at the

same time was long enough to ride over sastrugi and hummocky ice.

Messrs. Hagen

and Company did their work thoroughly well, and the sledges proved all

that I

could have desired. The next step

was to secure the furs

that the expedition would require, and for this purpose we went to

Drammen and

made the necessary arrangements with Mr. W. C. Miller. We selected

skins for

the sleeping-bags, taking those of young reindeer, with short thick

fur, less

liable to come out under conditions of dampness than is the fur of the

older

deer. Our furs did not make a very large order, for after the

experience of the Discovery expedition I decided

to use

fur only for the feet and hands and for the sleeping-bags, relying for

all

other purposes on woollen garments with an outer covering of wind-proof

material. I ordered three large sleeping-bags, to hold three men each,

and

twelve one-man bags. Each bag had the reindeer fur inside, and the

seams were

covered with leather, strongly sewn. The flaps overlapped about eight

inches,

and the head of the bag was sewn up to the top of the fly. There were

three

toggles for fastening the bag up when the man was inside. The toggles

were

about eight inches apart. The one-man bags weighed about ten pounds

when dry,

but of course the weight increased as they absorbed moisture when in

use. The foot-gear I

ordered consisted of

eighty pairs of ordinary finnesko, or reindeer fur boots, twelve pairs

of

special finnesko and sixty pairs of ski boots of various sizes. The

ordinary

finnesko is made from the skin of the reindeer stag's head, with the

fur

outside, and its shape is roughly that of a very large boot without any

laces.

It is large enough to hold the foot, several pairs of socks, and a

supply of

sennegrass, and it is a wonderfully comfortable and warm form of

foot-gear. The

special finnesko are made from the skin of the reindeer stag's legs,

but they

are not easily secured, for the reason that the native tribes, not

unreasonably, desire to keep the best goods for themselves. I had a man

sent to

Lapland to barter for finnesko of the best kind, but he only succeeded

in

getting twelve pairs. The ski boots are made of soft leather, with the

upper

coming right round under the sole, and a flat piece of leather sewn on

top of

the upper. They are made specially for use with ski, and are very

useful for

summer wear. They give the foot plenty of play and do not admit water.

The heel

is very low, so that the foot can rest firmly on the ski. I bought five

prepared reindeer skins for repairing, and a supply of repairing gear,

such as

sinew, needles, and waxed thread. I have

mentioned that sennegrass is

used in the finnesko. This is a dried grass of long fibre, with a

special

quality of absorbing moisture. I bought fifty kilos (110.25 lb.) in

Norway for

use on the expedition. The grass is sold in wisps, bound up tightly,

and when

the finnesko are being put on, some of it is teased out and a pad

placed along

the sole under the foot. Then when the boot has been pulled on more

grass is

stuffed round the heel. The grass absorbs the moisture that is given

off from

the skin, and prevents the sock freezing to the sole of the boot, which

would

then be difficult to remove at night. The grass is pulled out at night,

shaken

loose, and allowed to freeze. The moisture that has been collected

congeals in

the form of frost, and the greater part of it can be shaken away before

the

grass is replaced on the following morning. The grass is gradually used

up on

the march, and it is necessary to take a fairly large supply, but it is

very

light and takes up little room. I ordered from

Mr. Moller sixty

pairs of wolfskin and dogskin mite, made with the fur outside, and

sufficiently

long to protect the wrists. The mits had one compartment for the four

fingers

and another for the thumb, and they were worn over woollen gloves. They

were

easily slipped off when the use of the fingers was required, and they

were hung

round the neck with lamp-wick in order that they might not get lost on

the

march. The only other articles of equipment I ordered in Norway were

twelve

pairs of ski, which were supplied by Messrs. Hagen and Company. They

were not

used on the sledging journeys at all, but were useful around the winter

quarters. I stipulated that all the goods were to be delivered in

London by

June 15, 1907. THE NIMROD Before I left

Norway I paid a visit

to Sandyfjord in order to see whether I could come to terms with Mr. C.

Christiansen, the owner of the Bjorn, a ship specially built for polar

work,

which would have suited my purposes most admirably. She was a new

vessel of

about 700 tons burthen and with powerful triple-expansion engines,

better

equipped in every way than the fortyyear-old Nimrod,

but I found that I could not afford to buy her, much as I

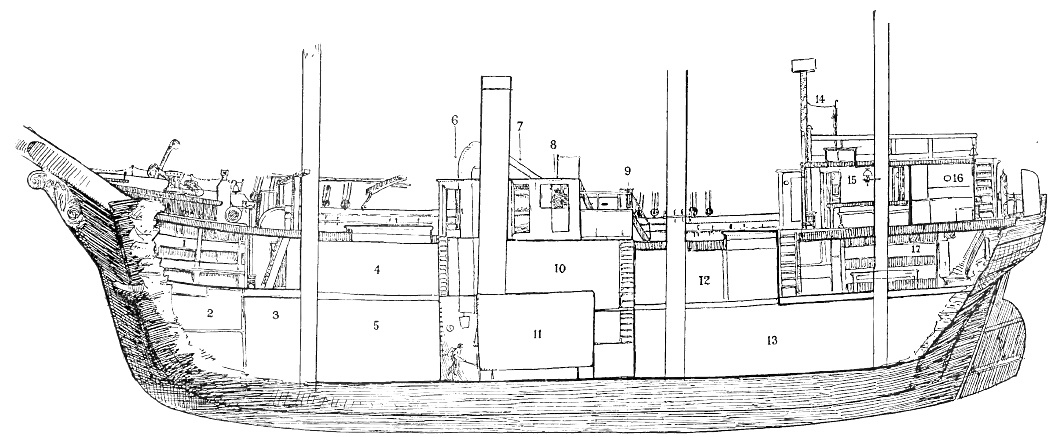

would have wished to do so.  1. Forecastle. 2. Stores. 8. Chain locker. 4. Fore hold. 6. Lower hold. 6. Stoke hold. 7. Carpenter's shop. 8. Cook's galley. 9. Engine room. 10. Engine room. 11. Boiler. 12. After hold. 18. Lower hold. 14. After bridge. 16. Officers' quarters. 16. Captain's quarters, 17, Oyster Alley. I proceeded at

once to put the ship

in the hands of Messrs. R. and H. Green, of Blackwall, the famous old

firm that

had built so many of Britain's "wooden walls," and that had done

fitting and repair work for several other polar expeditions. She was

docked for

the necessary caulking, and day by day assumed a more satisfactory

appearance.

The signs of former conflicts with the ice-floes disappeared, and the

masts and

running-gear were prepared for the troubled days that were to come.

Even the

penetrating odour of seal-oil ceased to offend after much vigorous

scrubbing of

decks and holds, and I began to feel that after all the Nimrod

would do the expedition no discredit. Later still I grew

really proud of the sturdy little ship. Quarters were

provided on board for

the scientific staff of the expedition by enclosing a portion of the

after-hold

and constructing cabins which were entered by a steep ladder from the

deck-house. The quarters were certainly small; for some Teason not on

record,

they were known later as "Oyster Alley." As the Nimrod,

after landing the shore-party

with stores and equipment,

would return to New Zealand it was necessary that we should have a

reliable hut

in which to live during the Antarctic night until the sledging journeys

commenced in the following spring. THE

HUT The hut would

be our only refuge

from the fury of the blizzards, and in it would be stored many articles

of

equipment as well as some of the food. A hut measuring (externally)

thirty-three feet by nineteen feet by eight feet to the eaves was

specially

constructed, to my order, by Messrs. Humphreys of Knightsbridge. After

being

erected and inspected in London, it was shipped in sections. It was made of

stout fir timbering

of best quality in walls, roofs, and floors, and the parts were all

morticed

and tenoned to facilitate erection in the Antarctic. The walls were

strengthened with iron cleats bolted to main posts and horizontal

timbering,

and the roof principals were provided with strong iron tie-rods. The

hut was

lined with match-boarding, and the walls and roof were covered

externally first

with strong roofing felt, then with one-inch tongued and grooved

boards, and

finally with another covering of felt. In addition to these precautions

against

the extreme cold the four-inch space in framing between the

match-boarding and

the first covering of felt was packed with granulated cork, which

assisted

materially to render the wall non-conducting. The hut was to be erected

on

wooden piles let into the ground or ice, and rings were fixed to the

apex of

the roof so that guy-ropes might be used to give additional resistance

to the

gales. The hut had two doors, connected by a smell porch, so that

ingress and

egress would not mean the admission of a draught of cold air; and the

windows

were double, in order that the warmth of the hut might be retained.

There were

two louvre ventilators in the roof, controlled from the inside. The hut

had no

fittings, and we took little furniture. I proposed to use cases for the

construction of benches, beds, and other necessary articles of internal

equipment. The hut was to be lit with acetylene gas, and we took a

generator,

the necessary piping, and a supply of carbide. The

cooking-range we used in the hut

was manufactured by Messrs. Smith and Wellstrood, of London, and was

four feet

wide by two feet four inches deep. It had a fire chamber designed to

burn

anthracite coal continuously day and night and to heat a large

superficial area

of outer plate, so that there might be plenty of warmth given off in

the hut.

The stove had two ovens and a chimney of galvanised steel pipe, capped

by a

revolving cowl. It was mounted on legs. CLOTHING Each member of

the expedition was

supplied with two winter suits made of heavy blue pilot cloth, lined

with

Jaeger fleece. A suit consisted of a double-breasted jacket, vest and

trousers,

and weighed complete fourteen and three-quarter pounds. The

underclothing was

secured from the Dr. Jaeger Sanitary Woollen Company. An outer suit

of windproof material

is necessary in the polar regions, and I secured twenty-four suits of

Burberry

gaberdine, each suit consisting of a short blouse, trouser overalls and

a

helmet cover. For use in the winter quarters we took four dozen Jaeger

camel-hair blankets and sixteen camel-hair triple sleeping-bags. PONIES,

DOGS,

AND MOTOR-CAR I decided to

take ponies, dogs, and

a motor-car to assist in hauling our sledges on the long journeys that

I had in

view, but my hopes were based mainly on the ponies. Dogs had not proved

satisfactory on the Barrier surface, and I had not expected my dogs to

do as

well as they actually did. I felt confident, however, that the hardy

ponies

used in Northern China and Manchuria would be useful if they could be

landed on

the ice in good condition. I had seen these ponies in Shanghai, and I

had heard

of the good work they did on the Jackson-Harmsworth expedition. They

are

accustomed to hauling heavy loads in a very low temperature, and they

are

hardy, sure-footed, and plucky. I noticed that they had been used with

success

for very rough work during the Russo-Japanese War, and a friend who had

lived

in Siberia gave me some more information regarding their capabilities. I therefore got

into communication

with the London manager of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (Mr. C. S.

Addis),

and he was able to secure the services of a leading firm of veterinary

surgeons

in Shanghai. A qualified man went to Tientsin on my behalf, and from a

mob of

about two thousand of the ponies, brought down for sale from the

northern

regions, he selected fifteen of the little animals for my expedition.

The

ponies chosen were all over twelve and under seventeen years of age,

and had

spent the early part of their lives in the interior of Manchuria. They

were

practically unbroken, about fourteen hands high, and of various

colours. They

were all splendidly strong and healthy, full of tricks and wickedness,

and

ready for any amount of hard work over the snow-fields. The fifteen

ponies were

taken to the coast and shipped by direct steamer to Australia. They

came

through the test of tropical temperatures unscathed, and at the end of

October

1908 arrived in Sydney, where they were met by Mr. Reid and at once

transferred

to a New Zealand bound steamer. The Colonial Governments kindly

consented to

suspend the quarantine restrictions, which would have entailed exposure

to

summer heat for many weeks, and thirty-five days after leaving China

the ponies

were landed on Quail Island in Port Lyttelton, and were free to scamper

about

and feed in idle luxury. I decided to

take a motor-car

because I thought it possible, from my previous experience, that we

might meet

with a hard surface on the Great Ice Barrier, over which the first

part, at any

rate, of the journey towards the south would have to be performed. On a

reasonably good surface the machine would be able to haul a heavy load

at a

rapid pace. I selected a 12-15 horse-power New Arrol-Johnston car,

fitted with

a specially designed air-cooled four-cylinder engine and Simms Bosch

magneto

ignition. Water could not be used for cooling, as it would certainly

freeze.

Round the carburetter was placed a small jacket, and the exhaust gases

from one

cylinder were passed through this in order that they might warm the

mixing

chamber before passing into the air. The exhaust from the other

cylinders was

conveyed into a silencer that was also to act as a foot-warmer. The

frame of

the car was of the standard pattern, but the manufacturers had taken

care to

secure the maximum of strength, in view of the fact that the car was

likely to

experience severe strains at low temperature. I ordered a good supply

of spare

parts in order to provide for breakages, and a special non-freezing oil

was

prepared for me by Messrs. Price and Company. Petrol was taken in the

ordinary

tins. I secured wheels of several special patterns as well as ordinary

wheels

with rubber tyres, and I had manufactured wooden runners to be placed

under the

front wheels for soft surfaces, the wheels resting in chocks on top of

the

runners. The car in its original form had two bracket seats, and a

large trough

behind for carrying stores. it was packed in a large case and lashed

firmly

amidships on the Nimrod, in which

position it made the journey to the Antarctic continent in safety.  SEAL SUCKLING YOUNG, AND TAKING NO NOTICE OF THE MOTOR-CAR I placed little

reliance on dogs, as

I have already stated, but I thought it advisable to take some of these

animals. I knew that a breeder in Stewart Island, New Zealand, had dogs

descended from the Siberian dogs used on the Newnes-Borchgrevink

expedition,

and I cabled to him to supply as many as he could up to forty. He was

only able

to let me have nine, but this team proved quite sufficient for the

purposes of

the expedition, as the arrival of pups brought the number up to

twenty-two

during the course of the work in the south. SCIENTIFIC

INSTRUMENTS The equipment

of a polar expedition

on the scientific side involved the expenditure of a large sum of money

and I

felt the pinch of necessary economies in this branch. I was lent three

chronometer watches by the Royal Geographical Society. I bought one

chronometer

watch, and three wardens of the Skinners' Company gave me one which

proved the

most accurate of all and was carried by me on the journey towards the

Pole. The

Geographical Society was able to

send forward an application made by me for the loan of some instruments

and

charts from the Admiralty, and that Department generously lent me the

articles

contained in the following list: 3 Lloyd-Creak

dip circles. 3 marine

chronometers. 1 station

pointer, 13 ft. 1 set of

charts, England to Cape and Cape to New Zealand. 1 set of

Antarctic charts. 1 set of charts

from New Zealand through Indian Ocean to

Aden. 1 set of

charts, New Zealand to Europe via Cape Horn. 12 deep-sea

thermometers. 2 marine

standard barometers. 1 navy-pattern ship's

telescope. 1 ship's

standard compass. 2 azimuth

mirrors (Lord Kelvin's type). 1 deep-sea

sounding machine. 3 heeling error

instruments. 1 3-in.

portable astronomical telescope. 1 Lucas deep

sea sounding machine. I placed an

order for further

scientific instruments with Messrs. Cary, Porter and Company, Limited,

of

London. Amongst other

instruments that we

had with us on the expedition was a four-inch transit theodolite, with

Reeve's

micrometers fitted to horizontal and vertical circles. The photographic

equipment

included nine cameras by various makers, plant for the dark-room, and a

large

stock of plates, films, and chemicals. We took also a cinematograph

machine in

order that we might place on record the curious movements and habits of

the

seals and penguins, and give the people at home a graphic idea of what

it means

to haul sledges over the ice and snow. MISCELLANEOUS The

miscellaneous articles of

equipment were too numerous to be mentioned here in any detail. I had

tried to

provide for every contingency, and the gear ranged from needles and

nails to a

Remington typewriter and two Singer sewing machines. There was a

gramophone to

provide us with music, and a printing press, with type, rollers, paper,

and

other necessaries, for the production of a book during the winter

night. We

even had hockey sticks and a football. |