| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Little Journeys To the Homes of Great Scientists Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

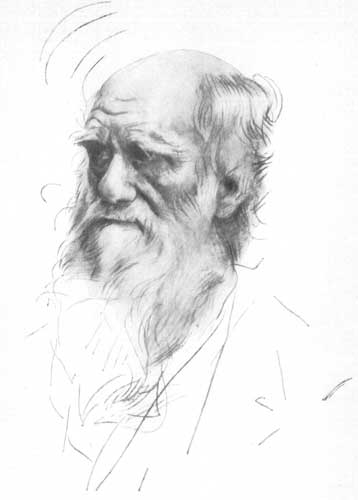

CHARLES DARWIN I feel most deeply that this whole question of Creation is too profound for human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton! Let each man hope and believe what he can. — Charles Darwin to Asa Gray

None have fought better, and none have been more fortunate, than Charles Darwin. He found a great truth trodden underfoot, reviled by bigots, and ridiculed by all the world; he lived long enough to see it, chiefly by his own efforts, irrefragably established in science, inseparably incorporated into the common thoughts of men. What shall a man desire more than this? — Thomas Huxley, — Address, April Twenty-seventh, Eighteen Hundred Eighty-two. CHARLES DARWIN

volution

is at work everywhere, even in the matter of jokes. Once in the

House of Commons, Benjamin Disraeli, who prided himself on his fine

scholarship

as well as on his Hyperion curl, interrupted a speaker and corrected

him on a

matter of history. volution

is at work everywhere, even in the matter of jokes. Once in the

House of Commons, Benjamin Disraeli, who prided himself on his fine

scholarship

as well as on his Hyperion curl, interrupted a speaker and corrected

him on a

matter of history. "I would rather be a gentleman than a scholar!" the man replied. "My friend is seldom either," came the quick response. When Thomas Brackett Reed was Speaker of the House of Representatives, a member once took exception to a ruling of the "Czar," and having in mind Reed's supposed Presidential aspirations closed his protests with the thrust, "I would rather be right than President." "The gentleman will never be either," came the instant retort. But some years before the reign of the American Czar, Gladstone, Premier of England, said, "I would rather be right and believe in the Bible, than excite a body of curious, infidelic, so-called scientists to unbecoming wonder by tracing their ancestry to a troglodyte." And Huxley replied, "I, too, would rather be right — I would rather be right than Premier." Charles Darwin was a Gentle Man. He was the greatest naturalist of his time, and a more perfect gentleman never lived. His son Francis said: "I can not remember ever hearing my father utter an unkind or hasty word. If in his presence some one was being harshly criticized, he always thought of something to say in way of palliation and excuse." One of his companions on the "Beagle," who saw him daily for five years on that memorable trip, wrote: "A protracted sea-voyage is a most severe test of friendship, and Darwin was the only man on our ship, or that I ever heard of, who stood the ordeal. He never lost his temper or made an unkind remark." Captain Fitz-Roy of the "Beagle" was a disciplinarian, and absolute in his authority, as a sea-captain must be. The ship had just left one of the South American ports where the captain had gone ashore and been entertained by a coffee-planter. On this plantation all the work was done by slaves, who, no doubt, were very well treated. The captain thought that negroes well cared for were very much better off than if free. And further, he related how the owner had called up various slaves and had the Captain ask them if they wished their freedom, and the answer was always, "No." Darwin interposed by asking the Captain what he thought the answer of a slave was worth when being interrogated in the presence of his owner. Here Fitz-Roy flew into a passion, berating the volunteer naturalist, and suggested a taste of the rope's end in lieu of logic. Young Darwin made no reply, and seemingly did not hear the uncalled-for chidings. In a few hours a sailor handed him a note from Captain Fitz-Roy, full of abject apology for having so forgotten himself. Darwin was then but twenty-two years old, but the poise and patience of the young man won the respect and then the admiration and finally the affection of every man on board that ship. This attitude of kindness, patience and good-will formed the strongest attribute of Darwin's nature, and to these godlike qualities he was heir from a royal line of ancestry. No man was ever more blest — more richly endowed by his parents with love and intellect — than Darwin. And no man ever repaid the debt of love more fully — all that he had received he gave again. Darwin is the Saint of Science. He proves the possible; and when mankind shall have evolved to a point where such men will be the rule, not the exception — as one in a million — then, and not until then, can we say we are a civilized people. Charles Darwin was not only the greatest thinker of his time (with possibly one exception), but in his simplicity and earnestness, in his limpid love for truth — his perfect willingness to abandon his opinion if he were found to be wrong — in all these things he proved himself the greatest man of his time. Yet it is absurd to try to separate the scientist from the father, neighbor and friend. Darwin's love for truth as a scientist was what lifted him out of the fog of whim and prejudice and set him apart as a man. He had no time to hate. He had no time to indulge in foolish debates and struggle for rhetorical mastery — he had his work to do. That statesmen like Gladstone misquoted him, and churchmen like Wilberforce reviled him — these things were as naught to Darwin — his face was toward the sunrising. To be able to know the truth, and to state it, were vital issues: whether the truth was accepted by this man or that was quite immaterial, except possibly to the man himself. There was no resentment in Darwin's nature. Only love is immortal — hate is a negative condition. It is love that animates, beautifies, benefits, refines, creates. So firmly was this truth fixed in the heart of Darwin that throughout his long life the only things he feared and shunned were hate and prejudice. "They hinder and blind a man to truth," he said — "a scientist must only love."

merson

has been called the culminating flower of

seven generations of New England culture. Charles Darwin seems a

similar

culminating product. merson

has been called the culminating flower of

seven generations of New England culture. Charles Darwin seems a

similar

culminating product. Surely he showed rare judgment in the selection of his grandparents. His grandfather on his father's side was Doctor Erasmus Darwin, a poet, a naturalist, and a physician so discerning that he once wrote: "The science of medicine will some time resolve itself into a science of prevention rather than a matter of cure. Man was made to be well, and the best medicine I know of is an active and intelligent interest in the world of Nature." Erasmus Darwin had the felicity to have his biography written in German, and he also has his place in the "Encyclopedia Britannica" quite independent of that of his gifted grandson. Charles Darwin's grandfather on his mother's side was Josiah Wedgwood, one of the most versatile of men. He was as fine in spirit as those exquisite designs by Flaxman that you will see today on the Wedgwood pottery. Josiah Wedgwood was a businessman — an organizer, and he was beyond this, an artist, a naturalist, a sociologist and a lover of his race. His portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds reveals a man of rare intelligence, and his biography is as interesting as a novel by Kipling. His space in the "Encyclopedia Britannica" is even more important than that occupied by his dear friend and neighbor, Doctor Erasmus Darwin. The hand of the Potter did not shake when Josiah Wedgwood was made. Josiah Wedgwood and Doctor Darwin had mutually promised their children in marriage. Wedgwood became rich and he made numerous other men rich, and he enriched the heart and the intellect of England by setting before it beautiful things, and by living an earnest, active and beautiful life. Josiah Wedgwood coined the word "queensware." He married his cousin, Sarah Wedgwood. Their daughter, Susannah Wedgwood, married Doctor Robert Darwin, and Charles Darwin, their son, married Emma Wedgwood, a daughter of Josiah Wedgwood the Second. Caroline Darwin, a sister of Charles Darwin, married Josiah Wedgwood the Third. Let those who have the time work out this origin of species in detail and show us the relationship of the Darwins and Wedgwoods. And I hope we'll hear no more about the folly of cousins marrying, when Charles Darwin is before us as an example of natural selection. From his mother Darwin inherited those traits of gentleness, insight, purity of purpose, patience and persistency that set him apart as a marked man. The father of Charles Darwin, Doctor Robert Darwin, was a most successful physician of Shrewsbury. His marriage to Susannah Wedgwood filled his heart, and also placed him on a firm financial footing, and he seemed to take his choice of patients. Doctor Darwin was a man devoted to his family, respected by his neighbors, and he lived long enough to see his son recognized, greatly to his surprise, as one of England's foremost scientists. Charles Darwin in youth was rather slow in intellect, and in form and feature far from handsome. Physically he was never strong. In disposition he was gentle and most lovable. His mother died when he was eight years of age, and his three older sisters then mothered him. Between them all existed a tie of affection, very gentle, and very firm. The girls knew that Charles would become an eminent man — just how they could not guess — but he would be a leader of men: they felt it in their hearts. It was all the beautiful dream that the mother has for her babe as she sings to the man-child a lullaby as the sun goes down. In his autobiographical sketch, written when he was past sixty, Darwin mentions this faith and love of his sisters, and says, "Personally, I never had much ambition, but when at college I felt that I must work, if for no other reason, so as not to disappoint my sisters." At school Charles was considerable of a grubber: he worked hard because he felt that it was his duty. English boarding-schools have always taught things out of season, and very often have succeeded in making learning wholly repugnant. Perhaps that is the reason why nine men out of ten who go to college cease all study as soon as they stand on "the threshold," looking at life ere they seize it by the tail and snap its head off. To them education is one thing and life another. But with many headaches and many heartaches Charles got through Cambridge and then was sent to attend lectures at the University of Edinburgh. Of one lecturer in Scotland he says, "The good man was really more dull than his books, and how I escaped without all science being utterly distasteful to me I hardly know." To Cambridge, Darwin owed nothing but the association with other minds, yet this was much, and almost justifies the college. "Send your sons to college and the boys will educate them," said Emerson. The most beneficent influence for Darwin at Cambridge was the friendship between himself and Professor Henslow. Darwin became known as "the man who walks with Henslow." The professor taught botany, and took his classes on tramps a-field and on barge rides down the river, giving out-of-door lectures on the way. This commonsense way of teaching appealed to Darwin greatly, and although he did not at Cambridge take up botany as a study, yet when Henslow had an out-of-door class he usually managed to go along. In his autobiography Darwin gives great credit to this very gentle and simple soul, who, although not being great as a thinker, yet could animate and arouse a pleasurable interest. Henslow was once admonished by the faculty for his lack of discipline, and young Darwin came near getting himself into difficulty by declaring, "Professor Henslow teaches his pupils in love; the others think they know a better way!" The hope of his father and sisters was that Charles Darwin would become a clergyman. For the army he had no taste whatsoever, and at twenty-one the only thing seemed to be the Church. Not that the young man was filled with religious zeal — far from that — but one must, you know, do something. Up to this time he had studied in a desultory way; he had also dreamed and tramped the fields. He had done considerable grouse-shooting and had developed a little too much skill in that particular line. To paraphrase Herbert Spencer, to shoot fairly well is a manly accomplishment, but to shoot too well is evidence of an ill-spent youth. Doctor Darwin was having fears that his son was going to be an idle sportsman, and he was urging the divinity-school. The real fact was that sportsmanship was already becoming distasteful to young Darwin, and his hunting expeditions were now largely carried on with a botanist's drum and a geologist's hammer. But to the practical Doctor these things were no better than the gun — it was idling, anyway. Natural History as a pastime was excellent, and sportsmanship for exercise and recreation had its place, but the business of life must not be neglected — Charles should get himself to a divinity-school, and quickly, too. Things urged become repellent; and Charles was groping around for an excuse when a letter came from Professor Henslow, saying, among other things, that the Government was about to send a ship around the world on a scientific surveying tour, especially to map the coast of Patagonia and other parts of South America and Australia. A volunteer naturalist was wanted — board and passage free, but the volunteer was to supply his own clothes and instruments. The proposition gave Charles a great thrill: he gave a gulp and a gasp and went in search of his father. The father saw nothing in the plan beyond the fact that the Government was going to get several years' work out of some foolish young man, for nothing — gadzooks! Charles insisted — he wanted to go! He urged that on this trip he would be to but very little expense. "You say I have cost you much, but the fellow who can spend money on board ship must be very clever." "But you are a very clever young man, they say," the father replied. That night Charles again insisted on discussing the matter. The father was exasperated and exclaimed, "Go and find me one sane man who will endorse your wild-goose chase and I will give my consent." Charles said no more — he would find that "sane man." But he knew perfectly well that if any average person endorsed the plan his father would declare the man was insane, and the proof of it lay in the fact that he endorsed the wild-goose chase. In the morning Charles started of his own accord to see Henslow. Henslow would endorse the trip, but both parties knew that Doctor Darwin would not accept a mere college professor as sane. Charles went home and tramped thirty miles across the country to the home of his uncle, Josiah Wedgwood the Second. There he knew he had an advocate for anything he might wish, in the person of his fair cousin, Emma. These two laid their heads together, made a plan and stalked their prey. They cornered Josiah the Second after dinner and showed him how it was the chance of a lifetime — this trip on H.M.S. the "Beagle"! Charles wasn't adapted for a clergyman, anyway; he wanted to be a ship-captain, a traveler, a discoverer, a scientist, an author like Sir John Mandeville, or something else. Josiah the Second had but to speak the word and Doctor Darwin would be silenced, and the recommendation of so great a man as Josiah Wedgwood would secure the place. Josiah the Second laughed — then he looked sober. He agreed with the proposition — it was the chance of a lifetime. He would go back home with Charles and put the Doctor straight. And he did. And on the personal endorsement of Josiah Wedgwood and Professor Henslow, Charles Robert Darwin was duly booked as Volunteer Naturalist in Her Majesty's service.

aptain

Fitz-Roy of the "Beagle" liked Charles Darwin until he

began to look him over with a very professional eye. Then he declared

his nose

was too large and was not rightly shaped; besides, he was too tall for

his

weight: outside of these points the Volunteer would answer. On talking

with

young Darwin further, the Captain liked him better, and he waived all

imperfections, although no promise was made that they would be

remedied. In

fact, Captain Fitz-Roy liked Charles so well that he invited him to

share his

own cabin and mess with him. The sailors, on seeing this, touched

respectful

forefingers to their caps and began addressing the Volunteer as

"Sir." aptain

Fitz-Roy of the "Beagle" liked Charles Darwin until he

began to look him over with a very professional eye. Then he declared

his nose

was too large and was not rightly shaped; besides, he was too tall for

his

weight: outside of these points the Volunteer would answer. On talking

with

young Darwin further, the Captain liked him better, and he waived all

imperfections, although no promise was made that they would be

remedied. In

fact, Captain Fitz-Roy liked Charles so well that he invited him to

share his

own cabin and mess with him. The sailors, on seeing this, touched

respectful

forefingers to their caps and began addressing the Volunteer as

"Sir." The "Beagle" sailed on December Twenty-seven, Eighteen Hundred Thirty-one, and it was fully four years and ten months before Charles Darwin saw England again. The trip decided the business of Darwin for the rest of his life, and thereby an epoch was worked in the upward and onward march of the race. Captain Fitz-Roy of the British Navy was but twenty-three years old. He was a draftsman, a geographer, a mathematician and a navigator. He had sailed around the world as a plain tar, and taken his kicks and cuffs with good grace. At the Portsmouth Naval School he had won a gold medal for proficiency in study, and another medal had been given him for heroism in leaping from a sailing-ship into the sea to save a drowning sailor. Let us be fair — the tight little island has produced men. To evolve these few good men she may have produced many millions of the spawn of earth, but let the fact stand — England has produced men. Here was a beardless youth, slight in form, silent by habit, but so well thought of by his Government that he was given charge of a ship, five officers, two surgeons and forty-one picked men to go around the world and make measurements of certain coral-reefs, and map the dangerous coasts of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. The ship was provisioned for two years, but the orders were, "Do the work, no matter how long it may take, and your drafts on the Government will be honored." Captain Fitz-Roy was a man of decision: he knew just where he wanted to go, and what there was to do. He was to measure and map dreary wastes of tossing tide, and to do the task so accurately that it would never have to be done again: his maps were to remain forever a solace, a safety and a security to the men who go down to the sea in ships. England has certainly produced men — and Fitz-Roy was one of them. Fitz-Roy is now known to us, not for his maps which have passed into the mutual wealth of the world, but because he took on this trip, merely as an afterthought, a volunteer naturalist. Before the "Beagle" sailed, Captain Fitz-Roy and young Mr. Darwin went down to Portsmouth, and the Captain showed him the ship. The Captain took pains to explain the worst. It was to be at least two years of close, unremitting toil. It was no pleasure-excursion — there were no amusements provided, no cards, no wine on the table; the fare was to be simple in the extreme. This way of putting the matter was most attractive to Darwin — Fitz-Roy became a hero in his eyes at once. The Captain's manner inspired much confidence — he was a man who did not have to be amused or cajoled. "You will be left alone to do your work," said Fitz-Roy to Darwin, "and I must have the cabin to myself when I ask for it." And that settled it. Life aboard ship is like life in jail. It means freedom, freedom from interruption — you have your evenings to yourself, and the days as well. Darwin admired every man on board the ship, and most of all, the man who selected them, and so wrote home to his sisters. He admired the men because each was intent on doing his work, and each one seemed to assume that his own particular work was really the most important. Second Officer Wickham was entrusted to see that the ship was in good order, and so thorough was he that he once said to Darwin, who was constantly casting his net for specimens, "If I were the skipper, I'd soon have you and your beastly belittlement out of this ship with all your devilish, damned mess." And Darwin, much amused, wrote this down in his journal, and added, "Wickham is a most capital fellow." The discipline and system of ship-life, the necessity of working in a small space, and of improving the calm weather, and seizing every moment when on shore, all tended to work in Darwin's nature exactly the habit that was needed to make him the greatest naturalist of his age. Every sort of life that lived in the sea was new and wonderful to him. Very early on this trip Darwin began to work on the "Cirripedia" (barnacles), and we hear of Captain Fitz-Roy obligingly hailing homeward-bound ships, and putting out a small boat, rowing alongside, asking politely, to the astonishment of the party hailed, "Would you oblige us with a few barnacles off the bottom of your ship?" All this that the Volunteer, who was dubbed the "Flycatcher," might have something upon which to work. When on shore a sailor was detailed by Captain Fitz-Roy just to attend the "Flycatcher," with a bag to carry the specimens, geological, botanical and zoological, and a cabin-boy was set apart to write notes. This boy, who afterward became Governor of Queens and a K.C.B., used in after years to boast a bit, and rightfully, of his share in producing "The Origin of Species." When urged to smoke, Darwin replied, "I am not making any new necessities for myself." When the weather was rough the "Flycatcher" was sick, much to the delight of Wickham; but if the ship was becalmed, Darwin came out and gloried in the sunshine, and in his work of dissecting, labeling, and writing memoranda and data. The sailors might curse the weather — he did not. Thus passed the days. At each stop many specimens were secured, and these were to be sorted and sifted out at leisure. On shore the Captain had his work to do, and it was only after a year that Darwin accidentally discovered that the sailor who was sent to carry his specimens was always armed with knife and revolver, and his orders were not so much to carry what Wickham called, "the damned plunder," as to see that no harm befell the "Flycatcher." Fitz-Roy's interest in the scientific work was only general: longitude and latitude, his twenty-four chronometers, his maps and constant soundings, with minute records, kept his time occupied. For Darwin and his specimens, however, he had a constantly growing respect, and when the long five-year trip was ended, Darwin realized that the gruff and grim Captain was indeed his friend. Captain Fitz-Roy had trouble with everybody on board in turn, thus proving his impartiality; but when parting was nigh, tears came to his eyes as he embraced Darwin, and said, with prophetic yet broken words, "The 'Beagle's' voyage may be remembered more through you than me — I hope it will be so!" And Darwin, too moved for speech, said nothing except through the pressure of his hand.

he

idea of evolution took a firm hold upon the mind of Darwin, in an

instant, one day while on board the "Beagle." From that very hour the

thought of the mutability of species was the one controlling impulse of

his

life. he

idea of evolution took a firm hold upon the mind of Darwin, in an

instant, one day while on board the "Beagle." From that very hour the

thought of the mutability of species was the one controlling impulse of

his

life. On his return from the trip around the world he found himself in possession of an immense mass of specimens and much data bearing directly upon the point that creation is still going on. That he could ever sort, sift and formulate his evidence on his own account, he never at this time imagined. Indeed, about all he thought he could do was to present his notes and specimens to some scientific society, in the hope that some of its members would go ahead and use the material. With this thought in mind he began to open correspondence with several of the universities and with various professors of science, and to his dismay found that no one was willing even to read his notes, much less house, prepare for preservation, and index his thousands of specimens. He read papers before different scientific societies, however, from time to time, and gradually in London it dawned upon the few thinkers that this modest and low-voiced young man was doing a little thinking on his own account. One man to whom he had offered the specimens bluntly explained to Darwin that his specimens and ideas were valuable to no one but himself, and it was folly to try to give such things away. Ideas are like children and should be cared for by their parents, and specimens are for the collector. Seeing the depression of the young man, this friend offered to present the matter to the Secretary of the Exchequer. Everything can be done when the right man takes hold of it: the sum of one thousand pounds was appropriated by the Treasury for Charles Darwin's use in bringing out a Government report of the voyage of the "Beagle." And Darwin set to work, refreshed, rejoiced and encouraged. He was living in London in modest quarters, solitary and alone. He was not handsome, and he lacked the dash and flash that make a success in society. On a trip to his old home, he walked across the country to see his uncle, Josiah Wedgwood the Second. When he left it was arranged that he should return in a month and marry his cousin, Emma Wedgwood. And it was all so done. One commentator said he married his cousin because he didn't know any other woman that would have him. But none was so unkind as to say that he married her in order to get rid of her, yet Henslow wondered how he ceased wooing science long enough to woo the lady. Doubtless the parents of both parties had a little to do with the arrangement, and in this instance it was beautiful and well. Darwin was married to his work, and no such fallacy as marrying a woman in order to educate her filled his mind. His wife was his mental mate, his devoted helper and friend. It is no small matter for a wife to be her husband's friend. Mrs. Darwin had no small aspirations of her own. She flew the futile Four-o'Clock and made no flannel nightgowns for Fijis. Twenty years after his marriage, Darwin wrote thus: "It is probably as you say — I have done an enormous amount of work. And this was only possible through the devotion of my wife, who, ignoring every idea of pleasure and comfort for herself, arranged in a thousand ways to give me joy and rest, peace and most valuable inspiration and assistance. If I occasionally lost faith in myself, she most certainly never did. Only two hours a day could I work, and these to her were sacred. She guarded me as a mother guards her babe, and I look back now and see how hopelessly undone I should have been without her." In Eighteen Hundred Forty-two, Darwin and his wife moved to the village of Down, County of Kent. The place where they lived was a rambling old stone house with ample garden. The country was rough and unbroken, and one might have imagined he was a thousand miles from London, instead of twenty. There were no aristocratic neighbors, no society to speak of. With the plain farmers and simple folk of the village Darwin was on good terms. He became treasurer of the local improvement society, and thereby was serenaded once a year by a brass band. We hear of the good old village rector once saying, "Mr. Darwin knows botany better than anybody this side of Kew; and although I am sorry to say that he seldom goes to church, yet he is a good neighbor and almost a model citizen." Together the clergyman and his neighbor discussed the merits of climbing roses, morning-glories and sweet-peas. Darwin met all and every one on terms of absolute equality, and never forced his scientific hypotheses upon any one. In fact, no one in the village imagined this quiet country gentleman in the dusty gray clothes that matched his full iron-gray beard was destined for a place in Westminster Abbey — no, not even himself! Darwin's father, seeing that the Government had recognized him, and that all the scientific societies of London were quite willing to do as much, settled on him an allowance that was ample for his simple wants. On the death of Doctor Darwin, Charles became possessed of an inheritance that brought him a yearly income of a little over five hundred pounds. Children came to bless this happy household — seven in all. With these Darwin was both comrade and teacher. Two hours a day were sacred to science, but outside of this time the children made the study their own, and littered the place with their collections gathered on heath and dale. The recognition of the "holy time" was strong in the minds of the children, so no prohibitions were needed. One daughter has written in familiar way of once wanting to go into her father's study for a forgotten pair of scissors. It was the "holy time," and she thought she could not wait, so she took off her shoes and entered in stocking feet, hoping to be unobserved. Her father was working at his microscope: he saw her, reached out one arm as she passed, drew her to him and kissed her forehead. The little girl never again trespassed — how could she, with the father that gave her only love! That there was no sternness in this recognition of the value of the working hours is further indicated in that little Francis, aged six, once put his head in the door and offered the father a sixpence if he would come out and play in the garden. For several years Darwin was village magistrate. Most of the cases brought before him were either for poaching or drunkenness. "He always seemed to be trying to find an excuse for the prisoner, and usually succeeded," says his son. One time, when a prosecuting attorney complained because he had discharged a prisoner, Darwin, who might have fined the impudent attorney for contempt of court, merely said: "Why, he's as good as we are. If tempted in the same way I am sure that I would have done as he has done. We can't blame a man for doing what he has to do!" This was poor reasoning from a legal point of view. Darwin afterward admitted that he didn't hear much of the evidence, as his mind was full of orchids, but the fellow looked sorry, and he really couldn't punish anybody who had simply made a mistake. The local legal lights gradually lost faith in Magistrate Darwin's peculiar brand of justice; he hadn't much respect for law, and once when a lawyer cited him the criminal code he said, "Tut, tut, that was made a hundred years ago!" Then he fined the man five shillings, and paid the fine himself, when he should have sent him to the workhouse for six months.

he

men who have most benefited the world have, almost without exception,

been looked down upon by the priestly class. That is to say, the men

upon whose

tombs society now carves the word Savior were outcasts and criminals in

their

day. he

men who have most benefited the world have, almost without exception,

been looked down upon by the priestly class. That is to say, the men

upon whose

tombs society now carves the word Savior were outcasts and criminals in

their

day. In a society where the priest is regarded as the mouthpiece of divinity, and therefore the highest type of man, the artist, the inventor, the discoverer, the genius, the man of truth, has always been regarded as a criminal. Society advances as it doubts the priest, distrusts his oracles, and loses faith in his institution. In the priest, at first, was deposited all human knowledge, and what he did not know he pretended to know. He was the guardian of mind and morals, and the cure of souls. To question him was to die here and be damned for eternity. The problem of civilization has been to get the truth past the preacher to the people: he has forever barred and blocked the way, and until he was shorn of his temporal power there was no hope. The prisons were first made for those who doubted the priest; behind and beneath every episcopal residence were dungeons; the ferocious and delicate tortures that reached every physical and mental nerve were his. His anathemas and curses were always quickly turned upon the strong men of mountain or sea who dared live natural lives, said what they thought was truth, or did what they deemed was right. Science is a search for truth, but theology is a clutch for power. Nothing is so distasteful to a priest as freedom: a happy, exuberant, fearless, self-sufficient and radiant man he both feared and abhorred. A free soul was regarded by the Church as one to be dealt with. The priest has ever put a premium on pretense and hypocrisy. Nothing recommended a man more than humility and the acknowledgment that he was a worm of the dust. The ability to do and dare was in itself considered a proof of depravity. The education of the young has been monopolized by priests in order to perpetuate the fallacies of theology, and all endeavor to put education on a footing of usefulness and utility has been fought inch by inch. Andrew D. White, in his book, "The Warfare of Science and Religion," has calmly and without heat sketched the war that Science has had to make to reach the light. Slowly, stubbornly, insolently, theology has fought Truth step by step — but always retreating, taking refuge first behind one subterfuge, then another. When an alleged fact was found to be a fallacy, we were told it was not a literal fact, simply a spiritual one. All of theology's weapons have been taken from her and placed in the Museum of Horrors — all save one, namely, social ostracism. And this consists in a refusal to invite Science to indulge in cream-puffs. We smile, knowing that the man who now successfully defies theology is the only one she really, yet secretly, admires. If he does not run after her, she holds true the poetic unities by running after him. Mankind is emancipated (or partially so). Darwin's fame rests, for the most part, on two books, "The Origin of Species" and "The Descent of Man." Yet before these were published he had issued "A Journal of Research into Geology and Natural History," "The Zoology of the Voyage of the 'Beagle,'" "A Treatise on Coral Reefs, Volcanic Islands, Geological Observations," and "A Monograph of the Cirripedia." Had Darwin died before "The Origin of Species" was published, he would have been famous among scientific men, although it was the abuse of theologians on the publication of "The Origin of Species" that really made him world-famous. Alfred Russel Wallace, Darwin's chief competitor said that "A Monograph on the Cirripedia" is enough upon which to found a deathless reputation. Darwin was equally eminent in Geology, Botany and Zoology. On November Twenty-fourth, Eighteen Hundred Fifty-nine, was published "The Origin of Species." Murray had hesitated about accepting the work, but on the earnest solicitation of Sir Charles Lyell, who gave his personal guarantee to the publisher against loss, quite unknown to Darwin, twelve hundred copies of the book were printed. The edition was sold in one day, and who was surprised most, the author or the publisher, it is difficult to say. Up to this time theology had stood solidly on the biblical assertion that mankind had sprung from one man and one woman, and that in the beginning every species was fixed and immutable. Aristotle, three hundred years before Christ, had suggested that, by cross-fertilization and change of environment, new species had been and were being evoked. But the Church had declared Aristotle a heathen, and in every school and college of Christendom it was taught that the world and everything in it was created in six days of twenty-four hours each, and that this occurred four thousand and four years before Christ, on May Tenth. Those who doubted or disputed this statement had no standing in society, and in truth, until the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, were in actual danger of death — heresy and treason being usually regarded as the same thing. Erasmus Darwin had taught that species were not immutable, but his words were so veiled in the language of poesy that they naturally went unchallenged. But now the grandson of Doctor Erasmus Darwin came forward with the net result of thirty years' continuous work. "The Origin of Species" did not attack any one's religious belief — in fact, in it the biblical account of Creation is not once referred to. It was a calm, judicial record of close study and observation, that seemed to prove that life began in very lowly forms, and that it has constantly ascended and differentiated, new forms and new species being continually created, and that the work of creation still goes on. In the preface to "The Origin of Species" Darwin gives Alfred Russel Wallace credit for coming to the same conclusion as himself, and states that both had been at work on the same idea for more than a score of years, but each working separately, unknown to the other. Andrew D. White says that the publication of Charles Darwin's book was like plowing into an ant-hill. The theologians, rudely awakened from comfort and repose, swarmed out angry, wrathful and confused. The air was charged with challenges; and soggy sermons, books, pamphlets, brochures and reviews, all were flying at the head of poor Darwin. The questions that he had anticipated and answered at great length were flung off by men who had neither read his book nor expected an answer. The idea that man had evolved from a lower form of animal especially was considered immensely funny, and jokes about "monkey ancestry" came from almost every pulpit, convulsing the pews with laughter. In passing, it may be well to note that Darwin nowhere says that man descended from a monkey. He does, however, affirm his belief that they had a common ancestor. One branch of the family took to the plains, and evolved into men, and the other branch remained in the woods and are monkeys still. The expression, "the missing link," is nowhere used by Darwin — that was a creation of one of his critics. Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, summed up the argument against Darwinism in the "Quarterly Review," by declaring that "Darwin was guilty of an attempt to limit the power of God"; that his book "contradicts the Bible"; that "it dishonors Nature." And in a speech before the British Association for the Advancement of Science, where Darwin was not present, the Bishop repeated his assertions, and turning to Huxley, asked if he were really descended from a monkey, and if so, was it on his father's or his mother's side! Huxley sat silent, refusing to reply, but the audience began to clamor, and Huxley slowly arose, and calmly but forcibly said: "I assert, and I repeat, that a man has no reason to be ashamed of having an ape for his grandfather. If there were an ancestor whom I should feel shame in recalling, it would be a man, a man of restless and versatile intellect, who, not content with success in his own sphere of activity, plunges into scientific questions with which he has no real acquaintance, only to obscure them by an aimless rhetoric, and distract the attention of his hearers from the real point at issue by eloquent digression and a skilful appeal to religious prejudices." Captain Fitz-Roy, who was present at this meeting, was also called for. He was now Admiral Fitz-Roy, and felt compelled to uphold his employer, the State, so he upheld the State Religion and backed up the Bishop of Oxford in his emptiness. "I often had occasion on board the 'Beagle' to reprove Mr. Darwin for his disbelief in the First Chapter of Genesis," solemnly said the Admiral. And Francis Darwin writes it down without comment, probably to show how much the Volunteer Naturalist was helped, aided and inspired by the Captain of the Expedition. But the reply of Huxley was a shot heard round the world, and for the most part the echo was passed along by the enemy. Huxley had insulted the Church, they said, and the adherents of the Mosaic account took the attitude of outraged and injured innocence. As for himself, Darwin said nothing. He ceased to attend the meetings of the scientific societies, for fear that he would be drawn into debate, and while he felt a sincere gratitude for Huxley's friendship, he deprecated the stern rebuke to the Bishop of Oxford. "It will arouse the opposition to greater unreason," he said. And this was exactly what happened. Even the English Catholics took sides with Wilberforce, the Protestant, and Cardinal Manning organized a society "to fight this new, so-called science that declares there is no God and that Adam was an ape." Even the Non-Conformists and Jews came in, and there was the very peculiar spectacle witnessed of the Church of England, the Non-Conformists, the Catholics and the Jews aroused and standing as one man, against one quiet villager who remained at home and said, "If my book can not stand the bombardment, why then it deserves to go down and to be forgotten." Spurgeon declared that Darwinism was more dangerous than open and avowed infidelity, since "the one motive of the whole book is to dethrone God." Rabbi Hirschberg wrote, "Darwin's volume is plausible to the unthinking person; but a deeper insight shows a mephitic desire to overthrow the Mosaic books and to bury Judaism under a mass of fanciful rubbish." In America Darwin had no more persistent critic than the Reverend DeWitt Talmage. For ten years Doctor Talmage scarcely preached a sermon without making reference to "monkey ancestry" and "baboon unbelievers." The New York "Christian Advocate" declared, "Darwin is endeavoring to becloud and befog the whole question of truth, and his book will be of short life." An eminent Catholic physician and writer, Doctor Constantine James, wrote a book of three hundred pages called "Darwinism, or the Man-Ape." A copy of Doctor James' book being sent to Pope Pius the Ninth, the Pope acknowledged it in a personal letter, thanking the author for his "masterly refutations of the vagaries of this man Darwin, wherein the Creator is left out of all things and man proclaims himself independent, his own king, his own priest, his own God — then degrading man to the level of the brute by declaring he had the same origin, and this origin was lifeless matter. Could folly and pride go further than to degrade Science into a vehicle for throwing contumely and disrespect on our holy religion!" This makes rather interesting reading now for those who believe in the infallibility of popes. So well did Doctor James' book sell, coupled with the approbation of the Pope, that as late as Eighteen Hundred Eighty-two a new and enlarged edition made its appearance, and the author was made a member of the Papal Order of Saint Sylvester. It is quite needless to add that those who read Doctor James' book refuting Darwin had never read Darwin, since "The Origin of Species" was placed on the "Index Expurgatorius" in Eighteen Hundred Sixty. Some years after, when it was discovered that Darwin had written other books, these were likewise honored. The book on barnacles being called to the attention of the Censor, that worthy exclaimed, "Some new heresy, I dare say — put it on the 'Index!'" And it was so done. The success of Doctor James' book reveals the popularity of the form of reasoning that digests the refutation first, and the original proposition not at all. In Eighteen Hundred Seventy-five, Gladstone in an address at Liverpool said, "Upon the ground of what is called evolution, God is relieved from the labor of creation and of governing the universe." Herbert Spencer called Gladstone's attention to the fact that Sir Isaac Newton, with his law of gravitation and the physical science of astronomy, was open to the same charge. Gladstone then took refuge in the "Contemporary Review," and retreated in a cloud of words that had nothing to do with the subject. Thomas Carlyle, who has facetiously been called a liberal thinker, had not the patience to discuss Darwin's book seriously, but grew red in the face and hissed in falsetto when it was even mentioned. He wrote of Darwin as "the apostle of dirt," and said, "He thinks his grandfather was a chimpanzee, and I suppose he is right — leastwise, I am not the one to deprive him of the honor." Scathing criticisms were uttered on Darwin's ideas, both on the platform and in print, by Doctor Noah Porter of Yale, Doctor Hodge of Princeton, and Doctor Tayler Lewis of Union College. Agassiz, the man who was regarded as the foremost scientist in America, thought he had to choose between orthodoxy and Darwinism, and he chose orthodoxy. His gifted son tried to rescue his father from the grip of prejudice, and later endeavored to free his name from the charge that he could not change his mind, but alas! Louis Agassiz's words were expressed in print, and widely circulated. There were two men in America whose names stand out like beacon-lights because they had the courage to speak up loud and clear for Charles Darwin while the pack was baying the loudest. These men were Doctor Asa Gray, who influenced the Appletons to publish an American edition of "The Origin of Species," and Professor Edward L. Youmans, who gave up his own brilliant lecture work in order that he might stand by Darwin, Spencer, Huxley and Wallace. For the man who was known as "a Darwinian" there was no place in the American Lyceum. Shut out from addressing the public by word of mouth, Youmans founded a magazine that he might express himself, and he fired a monthly broadside from his "Popular Science Monthly." And it is good to remember that the faith of Youmans was not without its reward. He lived to see his periodical grow from a confessed failure — a bill of expense that took his monthly salary to maintain — to a paying property that made its owner passing rich. Gray, too, outlived the charge of infidelity, and was not forced to resign his position as Professor at Harvard, as was freely prophesied he would. As for Darwin himself, he stood the storm of misunderstanding and abuse without scorn or resentment. "Truth must fight its way," he said; "and this gauntlet of criticism is all for the best. What is true in my book will survive, and that which is error will be blown away as chaff." He was neither exalted by praise nor cast down by censure. For Huxley, Lyell, Hooker, Spencer, Wallace and Asa Gray he had a great and profound love — what they said affected him deeply, and their steadfast kindness at times touched him to tears. For the great, seething, outside world that had not thought along abstruse scientific lines, and could not, he cared little. "How can we expect them to see as we do," he wrote to Gray; "it has taken me thirty years of toil and research to come to these conclusions. To have the unthinking masses accept all that I say would be calamity: this opposition is a winnowing process, and all a part of the Law of Evolution that works for good."

or

forty years Darwin lived in the same house at Down, in the same

quiet, simple way. Here he lived and worked, and the world gradually

came to

him, figuratively and literally. Gradually it dawned upon the

theologians that a

God who could set in motion natural laws that worked with beneficent

and

absolute regularity was just as great as if He had made everything at

once and

then stopped. or

forty years Darwin lived in the same house at Down, in the same

quiet, simple way. Here he lived and worked, and the world gradually

came to

him, figuratively and literally. Gradually it dawned upon the

theologians that a

God who could set in motion natural laws that worked with beneficent

and

absolute regularity was just as great as if He had made everything at

once and

then stopped. The miracle of evolution is just as sublime as the miracle of Adam's deep sleep and the making of a woman out of a man's rib. The faith of the scientist who sees order, regularity and unfailing law is quite as great as that of a preacher who believes everything he reads in a book. The scientist is a man with faith, plus. When Darwin died, in Eighteen Hundred Eighty-two, Darwinism and infidelity were words no longer synonymous. The discrepancies and inconsistencies of the theories of Darwin were seen by him as by his critics, and he was ever willing to admit the doubt. None of his disciples was as ready to modify his opinions as he. "We must beware of making science dogmatic," he once said to Haeckel. And at another time he said, "I would feel I had gone too far were it not for Wallace, who came to the same conclusions, quite independently of me." Darwin's mind was simple and childlike. He was a student, always learning, and no one was too mean or too poor for him to learn from. The patience, persistency and untiring industry of the man, combined with the daring imagination that saw the thing clearly long before he could prove it, and the gentle forbearance in the presence of unkindness and misunderstanding, won the love of a nation. He wished to be buried in the churchyard at Down, but at his death, by universal acclaim, the gates of Westminster swung wide to receive the dust of the man whom bishops, clergy and laymen alike had reviled. Darwin had won, not alone because he was right, but because his was a truly great and loving soul — a soul without the least resentment. Archdeacon Farrar, quoting Huxley, said, "I would rather be Darwin and be right than be Premier of England — we have had and will have many Premiers, but the world will never have another Darwin." |