| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Little Journeys To the Homes of Great Scientists Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

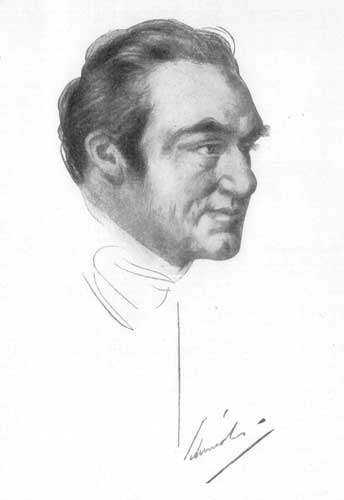

WILLIAM HERSCHEL

The great number of

alterations

of stars that we are certain have happened within the last two

centuries, and

the much greater number that we have reason to suspect to have taken

place, are

curious features in the history of the heavens, as curious as the slow

wearing

away of the landmarks of our earth on mountains, on river banks, on

ocean

shores. If we consider how little attention has formerly been paid this

subject, and that most of the observations we have are of a very late

date, it

would perhaps not appear extraordinary were we to admit the number of

alterations that have probably happened to different stars, within our

own

time, to be a hundred. William Herschel. WILLIAM

HERSCHEL  illiam Herschel, born

Seventeen Hundred Thirty-eight, in the city of

Hanover, was the fourth child in a family of ten. Big families, I am

told,

usually live in little houses, while little families live in big

houses. The

Herschels were no exception to the rule. illiam Herschel, born

Seventeen Hundred Thirty-eight, in the city of

Hanover, was the fourth child in a family of ten. Big families, I am

told,

usually live in little houses, while little families live in big

houses. The

Herschels were no exception to the rule.Isaac Herschel, known to

the

world as being the father of his son, was a poor man, depending for

support

upon his meager salary as bandmaster to a regiment of the Hanoverian

Guards. At the garrison school,

taught by

a retired captain, William was the star scholar. In mathematics he

propounded

problems that made the worthy captain pooh-pooh and change the subject. At fourteen, he was

playing a

hautboy in his father's band and practising on the violin at spare

times. For music he had a

veritable

passion, and to have a passion for a thing means that you excel in it

excellence

is a matter of intensity. One of the players in the band was a

Frenchman, and

William made an arrangement to give the "parlez vous" lessons on the

violin as payment for lessons in French. This whole brood of

Herschel

children was musical, and very early in life the young Herschels became

self-supporting as singers and players. "It is the only thing they can

do," their father said. But his loins were wiser than his head. In Seventeen Hundred

Fifty-five

William accompanied his father's band to England, where they went to

take part

in a demonstration in honor of a Hanoverian, one George the Third, who

later

was to play a necessary part in a symphony that was to edify the

American

Colonies. America owes much to George the Third. Young Herschel had

already

learned to speak English, just as he had learned French. In England he

spent

all the money he had for three volumes of "Locke on the Human

Understanding." These books were to

remain his

lifelong possession and to be passed on, well-thumbed, to his son more

than

half a century later. At the time of the

breaking out

of the Seven Years' War, William Herschel was nineteen. His regiment

had been

ordered to march in a week. Here was a pivotal point should he go and

fight

for the glory of Prussia? Not he by the

connivance of his

mother and sisters, he was secreted on a trading-sloop bound for

England. This

is what is called desertion; and just how the young man evaded the

penalties,

since the King of England was also Elector of Hanover, I do not know,

but the

House of Hanover made no effort toward punishment of the culprit, even

when the

facts were known. Musicians of quality

were,

perhaps, needed in England; and as sheep-stealing is looked upon

lightly by

priests who love mutton, so do kings forgive infractions if they need

the man. When William Herschel

landed at

Dover he had in his pocket a single crownpiece, and his luggage

consisted of

the clothes he wore, and a violin. The violin secured him board and

lodgings

along the road as he walked to London, just as Oliver Goldsmith paid

his way

with a similar legal tender. In London, Herschel's

musical

skill quickly got him an engagement at one of the theaters. In a few

months we

hear of his playing solos at Brabandt's aristocratic concerts. Little

journeys

into "the provinces" were taken by the orchestra to which Herschel

belonged. Among other places visited was Bath, and here the troupe was

booked

for a two-weeks' engagement. At this time Bath was run wide open. Bath was a rendezvous for

the

gouty dignitaries of Church and State who had grown swag through sloth

and much

travel by the gorge route. There were ministers of state, soldiers,

admirals-of-the-sea, promoters, preachers, philosophers, players,

poets, polite

gamblers and buffoons. They idled, fiddled,

danced,

gabbled, gadded and gossiped. The "School for Scandal" was written on

the spot, with models drawn from life. It wasn't a play it was a

cross-section of Bath Society. Bath was a clearing-house

for the

wit, learning and folly of all England the combined Hot Springs,

Coney

Island, Saratoga and Old Point Comfort of the Kingdom. The most costly

church

of its size in America is at Saint Augustine, Florida. The repentant

ones

patronize it in Lent; the rest of the year it is closed. At Bath there was the

Octagon

Chapel, which had the best pipe-organ in England. Herschel played the

organ:

where he learned how nobody seemed to know he himself did not know.

But

playing musical instruments is a little like learning a new language. A man who speaks three

languages

can take a day off and learn a fourth almost any time. Somebody has

said that

there is really only one language, and most of us have only a dialect.

Acquire

three languages and you perceive that there is a universal basis upon

which the

various tongues are built. Herschel could play the

hautboy,

the violin and the harpsichord. The organ came easy. When he played the

organ

in the Chapel at Bath, fair ladies forgot the Pump-Room, and the

gallants

followed them naturally. Herschel became the rage. He was a handsome

fellow,

with a pride so supreme that it completed the circle, and people called

it

humility. He talked but little, and made himself scarce a point every

genius

should ponder well. The disarming of the

populace confiscating

canes, umbrellas and parasols before allowing people to enter an

art-gallery

is necessary; although it is a peculiar comment on humanity to think

people

have a tendency to smite, punch, prod and poke beautiful things. The

same

propensity manifests itself in wishing to fumble a genius. Get your

coarse

hands on Richard Mansfield if you can! Corral Maude Adams hardly. To

do big

things, to create, breaks down tissue awfully, and to mix it with

society and

still do big things for society is impossible. At Bath, Herschel was

never seen

in the Pump-Room, nor on the North Parade. People who saw him paid for

the

privilege. "In England about this time look out for a shower of

genius," the almanackers might have said. To Bath came two

Irishmen, Edmund

Burke and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Burke rented rooms of Doctor

Nugent, and

married the doctor's daughter, and never regretted it. Sheridan also

married a

Bath girl, but added the right touch of romance by keeping the matter

secret,

with the intent that if either party wished to back out of the

agreement it

would be allowed. This was quite Irish-like, since according to English

Law a

marriage is a marriage until Limbus congeals and is used for a

skating-rink. With the true spirit of

chivalry,

Sheridan left the questions of publicity or secrecy to his wife: she

could have

her freedom if she wished. He was a fledgling barrister, with his

future in

front of him, the child of "strolling players"; she, the beautiful

Miss Linlay, was a singer of note. Her father was the leader of the

Bath

Orchestra, and had a School of Oratory where young people agitated the

atmosphere in orotund and tremolo and made the ether vibrate in glee.

Doctor

Linlay's daughter was his finest pupil, and with her were elucidated

all his

theories concerning the Sixteen Perspective Laws of Art. She also

proved a few

points in stirpiculture. She was a most beautiful girl of seventeen

when

Richard Brinsley Sheridan led her to the altar, or I should say to a

Dissenting

Pastor's back door by night. She could sing, recite, act, and

impersonate in

pantomime and Greek gown, the passions of Fear, Hate, Supplication,

Horror,

Revenge, Jealousy, Rage and Faith. Romney moved down to Bath

just so

as to have Miss Linlay and Lady Hamilton for models. He posed Miss

Linlay as

the Madonna, Beulah, Rena, Ruth, Miriam and Cecilia; and Lady Hamilton

for

Susannah at the Bath, Alicia and Andromache, and also had her

illustrate the

Virtues, Graces, Fates and Passions. When the beautiful Miss

Linlay,

the pride and pet of Bath, got ready to announce her marriage, she did

it by

simply changing the inscription beneath a Romney portrait that hung in

the

anteroom of the artist's studio, marking out the words "Miss Linlay,"

and writing over it, "Mrs. Richard Brinsley Sheridan." The Bath porchers who

looked

after other people's business, having none of their own, burbled and

chortled

like siphons of soda, and the marvel to all was that such a brilliant

girl

should thus throw herself away on a sprig of the law. "He acts, too, I

believe," said Goldsmith to Doctor Johnson. And Doctor Johnson said,

"Sir, he does nothing else," thus anticipating James McNeil Whistler

by more than a hundred years. But alas for the luckless

Linlay,

the Delsarte of his day, poor man! he used words not to be found in

Johnson's

Dictionary, and outdid Cassius in the quarrel-scene to the Brutus of

Richard

Brinsley. But very soon things

settled down

they always do when mixed with time and all were happy, or

reasonably so,

forever after. Herschel resigned from

Brabandt's

Orchestra and remained in Bath. He taught music, played the organ,

became first

violinist for Professor Linlay and later led the orchestra when Linlay

was on

the road starring the one-night stands and his beautiful daughter. Things seemed to prosper

with the

kindly and talented German. He was reserved, intellectual, and was

respected by

the best. He was making money not as London brokers might count

money, but

prosperous for a mere music-teacher. And so there came a day

when he

bought out the school of Professor Linlay, and became proprietor and

leader of

the famous Bath Orchestra. But the talented Mrs.

Richard

Brinsley Sheridan was sorely missed a woman soloist of worth was

needed. Herschel thought and

pondered. He

tried candidates from London and a few from Paris. Some had voices, but

no

intellect. A very few had intellect, but were without voice. Some

thought they

had a voice when what they had was a disease. Other voices he tried and

found

guilty. Those who had voice and

spirit

had tempers like a tornado. Herschel decided to

educate a

soloist and assistant. To marry a woman for the sake of educating her

was risky

business he knew of men who had tried it for men have tried it

since the

time of the Cavemen. A bright thought came to

him! He

would go back to Deutschland and get one of his sisters, and bring her

over to

England to help him do his work just the very thing!  t was a most fortunate

stroke for Herschel when he went back home to get

one of his sisters to come over into Macedonia and help him. No man

ever did a

great work unless he was backed up by a good woman. There were five of

these

Herschel girls three were married, so they were out of the question,

and

another was engaged. This left Caroline as first, last and only choice.

Caroline was twenty-two and could sing a little. t was a most fortunate

stroke for Herschel when he went back home to get

one of his sisters to come over into Macedonia and help him. No man

ever did a

great work unless he was backed up by a good woman. There were five of

these

Herschel girls three were married, so they were out of the question,

and

another was engaged. This left Caroline as first, last and only choice.

Caroline was twenty-two and could sing a little.She had appeared in

concerts for

her father when a child. But when the father died, the girl was set to

work in

a dressmaking and millinery shop, to help support the big family. The

mother

didn't believe that women should be educated it unfitted them for

domesticity, and to speak of a woman as educated was to suggest that

she was a

poor housekeeper. In Greece of old,

educated women

were spoken of as "companions" and this meant that they were not

what you would call respectable. They were the intellectual companions

of men.

The Greek term of disrespect carried with it a trifle of a suggestion

not

intended, that is, that women who were not educated not intellectual

were

really not companionable but let that pass. It is curious how this

idea that

a woman is only a scullion and a drudge has permeated society until

even the

women themselves partake of the prejudice against themselves. Mother Herschel didn't

want her

daughters to become educated, nor study the science of music nor the

science of

anything. A goodly grocer of the Dutch School had been picked out as a

husband

for Caroline, and now if she went away her prospects were ruined Ach,

Mein

Gott! or words to that effect. And it was only on William's promise to

pay the

mother a weekly sum equal to the wages that Caroline received in the

dressmaking-shop that she gave consent to her daughter's going.

Caroline

arrived in England, wearing wooden shoon and hoops that were exceeding

Dutch,

but without a word of English. In order to be of positive use to her

brother,

she must acquire English and be able to sing not only sing well, but

remarkably well. In less than a year she was singing solo parts at her

brother's concerts, to the great delight of the aristocrats of Bath. They heard her sing, but

they did

not take her captive and submerge her in their fashionable follies as

they

would have liked to do. The sister and the

brother kept

close to their own rooms. Caroline was the housekeeper, and took a

pride in

being able to dispense with all outside help. She was small in figure,

petite,

face plain but full of animation. All of her spare time she devoted to

her

music. After the concerts she and her brother would leave the theater,

change

their clothes and then walk off into the country, getting back as late

as one

or two o'clock in the morning. On these midnight walks they used to

study the

stars and talk of the wonderful work of Kepler and Copernicus. There

were

various requests that Caroline should go to London and sing, but she

steadfastly refused to appear on a stage except where her brother led

the

orchestra. About this time Caroline wrote a letter home, which missive,

by the

way, is still in existence, in which she says: "William goes to bed

early

when there are no concerts or rehearsals. He has a bowl of milk on the

stand

beside him, and he reads Smith's 'Harmonics' and Ferguson's

'Astronomy.' I sit

sewing in the next room, and occasionally he will call to me to listen

while he

reads some passage that most pleases him. So he goes to sleep buried

beneath

his favorite authors, and his first thought in the morning is how to

obtain

instruments so we can study the harmonics of the sky." And a way was to

open: they were to make their own telescopes what larks! Brother and

sister

set to work studying the laws of optics. In a secondhand store they

found a

small Gregorian reflector which had an aperture of about two inches. This gave them a little

peep into

the heavens, but was really only a tantalization. They set to work making a

telescope-tube out of pasteboard. It was about eighteen feet long, and

the

"board" was made in the genuine pasteboard way by pasting sheet

after sheet of paper together until the substance was as thick and

solid as a

board. So this brother and

sister worked

at all odd hours pasting sheet after sheet of paper old letters, old

books with

occasional strips of cloth to give extra strength. Lenses were bought

in

London, and at last our precious musical pair, with astronomy for their

fad,

had the satisfaction of getting a view of Saturn that showed the rings. It need not be explained

that

astronomical observations must be made out of doors. Further, the whole

telescope must be out of doors so as to get an even temperature. This

is a fact

that the excellent astronomers of the Mikado of Japan did not know

until very

recently. It seems they constructed a costly telescope and housed it in

a

costly observatory-house, with an aperture barely large enough for the

big

telescope to be pointed out at the heavens. Inside, the astronomer had

a

comfortable fire, for the season was then Winter and the weather cold.

But the

wise man could see nothing and the belief was getting abroad that the

machine

was bewitched, or that their Yankee brothers had lawsonized the buyers,

when

our own David P. Todd, of Amherst, happened along and informed them

that the

heat-waves which arose from their warm room caused a perturbation in

the

atmosphere which made star-gazing impossible. At once they made their

house

over, with openings so as to insure an even temperature, and Prince

Fusiyama

Noguchi wrote to Professor Todd, making him a Knight of the Golden

Dragon on

special order of the heaven-born Mikado. The Herschels knew enough

of the

laws of heat and refraction to realize they must have an even

temperature, but

they forgot that pasteboard was porous. One night they left their

telescope out of doors, and a sudden shower transformed the straight

tube into

the arc of a circle. All attempts to straighten it were vain, so they

took out

the lenses and went to work making a tube of copper. In this, brother,

sister

and genius which is concentration and perseverance united to

overcome the

innate meanness of animate and inanimate things. A failure was not a

failure to

them it was an opportunity to meet a difficulty and overcome it. The partial success of

the new

telescope aroused the brother and the sister to fresh exertions. The

work had

been begun as a mere recreation a rest from the exactions of the

public which

they diverted and amused with their warblings, concussions and

vibrations. They were still amateur

astronomers, and the thought that they would ever be anything else had

not come

to them. But they wanted to get a better view of the heavens a view

through a

Newtonian reflecting-telescope. So they counted up their savings and

decided

that if they could get some instrument-maker in London to make them a

reflecting-telescope six feet long, they would be perfectly willing to

pay him

fifty pounds for it. This study of the skies was their only form of

dissipation, and even if it was a little expensive it enabled them to

escape

the Pump-Room rabble and flee boredom and introspection. A hunt was

taken

through London, but no one could be found who would make such an

instrument as

they wanted for the price they could afford to pay. They found,

however, an amateur

lens-polisher who offered to sell his tools, materials and instruments

for a

small sum. After consultation, the brother and sister bought him out.

So at the

price they expected to pay for a telescope they had a machine-shop on

their

hands. The work of grinding and

polishing lenses is a most delicate business. Only a person of infinite

patience and persistency can succeed at it. In Allegheny,

Pennsylvania, lives

John Brashear, who, by his own efforts, assisted by a noble wife,

graduated

from a rolling-mill and became a maker of telescopes. Brashear is practically

the one

telescope lens-maker of America since Alvan Clark resigned. There is no

competition in this line the difficulties are too appalling for the

average

man. The slightest accident or an unseen flaw, and the work of months

or years

goes into the dustbin of time, and all must be gone over again. So when we think of this

brother

and sister sailing away upon an unknown ocean working day after day,

night

after night, week after week, and month after month, discarding scores

of

specula which they had worked upon many weary hours in order to get the

glass

that would serve their purpose we must remove our hats in reverence. God sends great men in

groups.

From Seventeen Hundred Forty for the next thirty-five years the

intellectual

sky seemed full of shooting-stars. Watt had watched to a purpose his

mother's

teakettle; Boston Harbor was transformed into another kind of Hyson

dish;

Franklin had been busy with kite and key; Gibbon was writing his

"Decline

and Fall"; Fate was pitting the Pitts against Fox; Hume was challenging

worshipers of a Fetish and supplying arguments still bright with use;

Voltaire

and Rousseau were preparing the way for Madame Guillotine; Horace

Walpole was

printing marvelous books at his private press at Strawberry Hill;

Sheridan was

writing autobiographical comedies; David Garrick was mimicking his way

to

immortality; Gainsborough was working the apotheosis of a hat;

Reynolds,

Lawrence, Romney, and West, the American, were forming an English

School of

Art; George Washington and George the Third were linking their names

preparatory to sending them down the ages; Boswell was penning undying

gossip;

Blackstone was writing his "Commentaries" for legal lights unborn;

Thomas Paine was getting his name on the blacklist of orthodoxy; Burke,

the

Irishman, was polishing his brogue so that he might be known as

England's

greatest orator; the little Corsican was dreaming dreams of conquest;

Wellesley

was having presentiments of coming difficulties; Goldsmith was giving

dinners

with bailiffs for servants; Hastings was defending a suit where the

chief

participants were to die before a verdict was rendered; Captain Cook

was giving

to this world new lands; while William Herschel and his sister were

showing the

world still other worlds, till then unknown.  hen the brother and

sister had followed the subject of astronomy as far

as Ferguson had followed it, and knew all that he knew, they thought

they

surely would be content. hen the brother and

sister had followed the subject of astronomy as far

as Ferguson had followed it, and knew all that he knew, they thought

they

surely would be content.Progress depends upon

continually

being dissatisfied. Now Ferguson aggravated them by his limitations. In their music they

amused,

animated and inspired the fashionable idlers. William gave lessons to

his

private pupils, led his orchestra, played the organ and harpsichord,

and managed

to make ends meet, and would have gotten reasonably rich had he not

invested

his spare cash in lenses, brass tubes, eyepieces, specula and other

such

trifles, and stood most of the night out on the lawn peering at the sky. He had been studying

stars for

seven years before the Bath that he amused awoke to the fact that there

was a

genius among them. And this genius was not the idolized Beau Nash whose

statue

adorned the Pump-Room! No, it was the man whose back they saw at the

concerts. During all these years

Herschel

had worked alone, and he had scarcely ever mentioned the subject of

astronomy

with any one save his sister. One night, however, he

had moved

his telescope into the middle of the street to get away from the

shadows of the

houses. A doctor who had been out to answer a midnight call stopped at

the

unusual sight and asked if he might look through the instrument. Permission was

courteously

granted. The next day the doctor called on the astronomer to thank him

for the

privilege of looking through a better telescope than his own. The

doctor was

Sir William Watson, an amateur astronomer and all-round scientist, and

member

of the Royal Society of London. Herschel had held himself

high he

had not gossiped of his work with the populace, cheapening his thought

by

diluting it for cheap people. Watson saw that Herschel, working alone,

isolated, had surpassed the schools. There is a nugget of

wisdom in

Ibsen's remark, "The strongest man is he who stands alone," and

Kipling's paraphrase, "He travels the fastest who travels alone." The chance acquaintance

of

Herschel and Watson soon ripened into a very warm friendship. Herschel amused the

neurotics,

Watson dosed and blistered them both for a consideration. Each had a

beautiful contempt for the society they served. Watson's father was of

the

purple, while Herschel's was of the people, but both men belonged to

the

aristocracy of intellect. Watson introduced Herschel into the select

scientific

circle of London, where his fine reserve and dignity made their due

impress.

Herschel's first paper to the Royal Society, presented by Doctor

Watson, was on

the periodical star in Collo Ceti. The members of the Society, always

very

jealous and suspicious of outsiders, saw they had a thinker to deal

with. Some one carried the news

to Bath

a great astronomer was now among them! About this time Horace Walpole

said,

"Mr. Herschel will content me if, instead of a million worlds, he can

discover me thirteen colonies well inhabited by men and women, and can

annex

them to the Crown of Great Britain in lieu of those it has lost beyond

the

Atlantic." Bath society now took up

astronomy as a fad, and fashionable ladies named the planets both

backward and

forward from a blackboard list set up in the Pump-House by Fanny

Burney, the

clever one. Herschel was invited to

give

popular lectures on the music of the spheres. Herschel's music-parlors

were

besieged by good people who wanted to make engagements with him to look

through

his telescope. One good woman gave the

year,

month, day, hour and minute of her birth and wanted her fortune told.

Poor

Herschel declined, saying he knew nothing of astronomy, but could give

her

lessons in music if desired. In answer to the law of

supply

and demand, thus proving the efficacy of prayer, an itinerant

astronomer came

down from London and set up a five-foot telescope on the Parade and

solicited

the curious ones at a tuppence a peep. This itinerant interested the

populace

by telling them a few stories about the stars that were not recorded in

Ferguson, and passed out his cards showing where he could be consulted

as a

fortune-teller during the day. Herschel was once passing by this street

astronomer, who was crying his wares, and a sudden impulse coming over

him to

see how bad the man's lens might be, he stopped to take a peep at

Earth's

satellite. He handed out the usual tuppence, but the owner of the

telescope

loftily passed it back saying, "I takes no fee from a

fellow-philosopher!" This story went the

rounds, and

when it reached London it had been amended thus: Charles Fox was taking

a

ramble at Bath, ran across William Herschel at work, and mistaking him

for an

itinerant, the great statesman stopped, peeped through the aperture,

and then

passing out a tuppence moved along blissfully unaware of his error, for

Herschel being a perfect gentleman would not embarrass the great man by

refusing his copper. When Herschel was asked

if the

story was true he denied the whole fabric, which the knowing ones said

was

further proof of his gentlemanly instincts for a true gentleman will

always

lie under two conditions: first, to save a woman's honor; and second,

to save a

friend from embarrassment. As a profession, astrology has proved a

better

investment than astronomy. Astronomy has nothing to offer but abstract

truth, and

those who love astronomy must do so for truth's sake. Astronomical discoveries

can not

be covered by copyright or patent, nor can any new worlds be claimed as

private

property and financed by stock companies, frenzied or otherwise.

Astrology, on

the other hand, relates to love-affairs, vital statistics, goldmines,

misplaced

jewels and lost opportunities. Yet, in this year of

grace,

Nineteen Hundred Five, Boston newspapers carry a column devoted to

announcements of astrologers, while the Cambridge Astronomical

Observatory

never gets so much as a mention from one year's end to the other.

Besides that,

astronomers have to be supported by endowment mendicancy while

astrologers

are paid for their prophecies by the people whose destinies they

invent. This shows

us how far as a nation we have traveled on the stony road of Science. Science, forsooth? Oh,

yes, of

course science bang! bang! bang!  n the month of March, in

Seventeen Hundred Ninety-one, Herschel, by the

discovery of Uranus, found his place as a fixed star among the world's

great

astronomers. Years before this, William and Caroline had figured it out

that

there must be another planet in our system in order to account

plausibly for

the peculiar ellipses of the others. That is to say, they felt the

influence of

this seventh planet; its attractive force was realized, but where it

was they

could not tell. Its discovery by Herschel was quite accidental. He was

sweeping

the heavens for comets when this star came within his vision. Others

had seen

it, too, but had classified it as "a vagrant fixed star." n the month of March, in

Seventeen Hundred Ninety-one, Herschel, by the

discovery of Uranus, found his place as a fixed star among the world's

great

astronomers. Years before this, William and Caroline had figured it out

that

there must be another planet in our system in order to account

plausibly for

the peculiar ellipses of the others. That is to say, they felt the

influence of

this seventh planet; its attractive force was realized, but where it

was they

could not tell. Its discovery by Herschel was quite accidental. He was

sweeping

the heavens for comets when this star came within his vision. Others

had seen

it, too, but had classified it as "a vagrant fixed star."It was the work of

Herschel to

discover that it was not a fixed star, but had a defined and distinct

orbit

that could be calculated. To look up at the heavens and pick out a star

that

could only be seen with a telescope pick it out of millions and

ascertain its

movement seems like finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. The present method of

finding

asteroids and comets by means of photography is simple and easy. The

plate is

exposed in a frame that moves by clockwork with the earth, so as to

keep the

same field of stars steady on the glass. After two, three or four

hours'

exposure, the photograph will show the fixed stars, but the planets,

asteroids

and comets will reveal themselves as a white streak of light, showing

plainly

where the sitters moved. Herschel had to watch

each

particular star in person, whereas the photographic lens will watch a

thousand. How close and persistent

an

observer a man must be who, watching one star at a time, discovers the

one in a

million that moves, is apparent. Chance, surely, must also come to his

aid and

rescue if he succeeds. Herschel found his moving

star,

and at first mistook it for a comet. Later, he and Caroline were agreed

that it

was in very truth their long-looked-for planet. There are no

proprietary rights

in newly discovered worlds the reward is in the honor of the

discovery, just

as the best recompense for a good deed lies in having done it. The Royal Society was the

recording station, as Kiel, Greenwich and Harvard are now. Herschel

made haste

to get his new world on record through his kind neighbor, Doctor Watson. The Royal Society gave

out the

information, and soon various other telescopes corroborated the

discovery made

by the Bath musician. Herschel christened his new discovery "Georgium

Sidus," in honor of the King; but the star belonged as much to Germany

and

France as to England, and astronomers abroad scouted the idea of

peppering the

heavens with the names of nobodies. Several astronomers

suggested the

name "Herschel," if the discoverer would consent, but this he would

not do. Doctor Bode then named the new star "Uranus," and Uranus it

is, although perhaps with any other name 't would shine as bright. Herschel was forty-three

years

old when he discovered Uranus. He was still a professional musician,

and an

amateur astronomer. But it did not require

much

arguing on the part of Doctor Watson when he presented Herschel's name

for

membership in the Royal Society for that most respectable body of

scholars to

at once pass favorably on the nomination. As one member in seconding

the motion

put it, "Herschel honors us in accepting this membership, quite as much

as

we do him in granting it." And so the next paper

presented

by Herschel to the Royal Society appears on the record signed "William

Herschel, F.R.S." Some time afterwards, it

was to

appear, "William Herschel, F.R.S., LL.D. (Edinburgh)"; and then

"Sir William Herschel, F.R.S., LL.D., D.C.L. (Oxon)."  eorge the Third, in about

the year Seventeen Hundred Eighty-two, had

invited his distinguished Hanoverian countryman to become an attachι of

the

Court with the title of "Astronomer to the King." The

Astronomer-Royal, in charge of the Greenwich Observatory, was one

Doctor

Maskelyne, a man of much learning, a stickler for the fact, but with a

mustard-seed imagination. Being asked his opinion of Herschel he

assured the

company thus: "Herschel is a great musician a great musician!"

Afterwards Maskelyne explained that the reason Herschel saw more than

other

astronomers was because he had made himself a better telescope. eorge the Third, in about

the year Seventeen Hundred Eighty-two, had

invited his distinguished Hanoverian countryman to become an attachι of

the

Court with the title of "Astronomer to the King." The

Astronomer-Royal, in charge of the Greenwich Observatory, was one

Doctor

Maskelyne, a man of much learning, a stickler for the fact, but with a

mustard-seed imagination. Being asked his opinion of Herschel he

assured the

company thus: "Herschel is a great musician a great musician!"

Afterwards Maskelyne explained that the reason Herschel saw more than

other

astronomers was because he had made himself a better telescope.One real secret of

Herschel's

influence seems to have been his fine enthusiasm. He worked with such

vim, such

animation, that he radiated light on every side. He set others to work,

and his

love for astronomy as a science created a demand for telescopes, which

he

himself had to supply. It does not seem that he cared especially for

money all

he made he spent for new apparatus. He had a force of about a dozen men

making

telescopes. He worked with them in blouse and overalls, and not one of

his

workmen excelled him as a machinist. The King bought several of his

telescopes

for from one hundred to three hundred pounds each, and presented them

to

universities and learned societies throughout the world. One fine

telescope was

presented to the University of Gottingen, and Herschel was sent in

person to

present it. He was received with the greatest honors, and scientists

and

musicians vied with one another to do him homage. In Seventeen Hundred

Eighty-two

Herschel and his sister gave up their musical work and moved from Bath

to

quarters provided for them near Windsor Castle. Herschel's salary was

then the

modest sum of two hundred pounds a year. Caroline was honored with

the

title "Assistant to the King's Astronomer" with the stipend of fifty

pounds a year. It will thus be seen that the kingly idea of astronomy

had not

traveled far from what it was when every really respectable court had a

retinue

of singers, musicians, clowns, dancers, palmists and scientists to

amuse the

people somewhat ironically called "nobility." King George the Third

paid his Cook, Master of the Kennels, Chaplain and Astronomer the same

amount.

The father of Richard Brinsley Sheridan was "Elocutionist to the

King," and was paid a like sum. When Doctor Watson heard

that

Herschel was about to leave Bath he wrote, "Never bought King honor so

cheap." It was nominated in the

bond that

Herschel should act as "Guide to the heavens for the diversification of

visitors whenever His Majesty wills it." But it was also provided

that the

astronomer should be allowed to carry on the business of making and

selling his

telescopes. Herschel's enthusiasm for

his

beloved science never abated. But often his imagination outran his

facts. Great minds divine the

thing

first they see it with their inward eye. Yet there may be danger in

this, for

in one's anxiety to prove what he first only imagined, small proof

suffices.

Thus Herschel was for many years sure that the moon had an atmosphere

and was

inhabited; he thought that he had seen clear through the Milky Way and

discovered empty space beyond; he calculated distances, and announced

how far

Castor was from Pollux; he even made a guess as to how long it took for

a

gaseous nebula to resolve itself into a planetary system; he believed

the sun

was a molten mass of fire a thing that many believed until they saw

the

incandescent electric lamp and in various other ways made daring

prophecies

which science has not only failed to corroborate, but which we now know

to be

errors. But the intensity of his

nature

was both his virtue and his weakness. Men who do nothing and say

nothing are

never ridiculous. Those who hope much, believe much, and love much,

make

mistakes. Constant effort and

frequent

mistakes are the stepping-stones of genius. In all, Herschel

contributed

sixty-seven important papers to the proceedings of the Royal Society,

and in

one of these, which was written in his eightieth year, he says, "My

enthusiasm has occasionally led me astray, and I wish now to correct a

statement which I made to you twenty-eight years ago." He then

enumerates

some particular statement about the height of mountains in the moon,

and

corrects it. Truth was more to Herschel than consistency. Indeed, the

earnestness, purity of purpose, and simplicity of his mind stamp him as

one of

the world's great men. At Windsor he built a

two-story

observatory. In the wintertime every night when the stars could be

seen, was

sacred. No matter how cold the weather, he stood and watched; while

down below,

the faithful Caroline sat and recorded the observations that he called

down to

her. Caroline was his

confidante,

adviser, secretary, servant, friend. She had a telescope of her own,

and when

her brother did not need her services she swept the heavens on her own

account

for maverick comets. In her work she was eminently successful, and five

comets

at least are placed to her credit on the honor-roll by right of

priority. Her

discoveries were duly forwarded by her brother to the Royal Society for

record. Later, the King of

Prussia was to

honor her with a gold medal, and several learned societies elected her

an

honorary member. When Herschel reached the discreet age of fifty he

married the

worthy Mrs. John Pitt, former wife of a London merchant. It is believed

that

the marriage was arranged by the King in person, out of his great love

for both

parties. At any rate Miss Burney thought so. Miss Burney was Keeper of

the

Royal Wardrobe at the same salary that Herschel had been receiving

two

hundred pounds a year. She also took charge of the Court Gossip, with

various

volunteer assistants. "Gold, as well as stars, glitters for

astronomers," said little Miss Burney. "Mrs. Pitt is very rich, meek,

quiet, rather pretty and quite unobjectionable." But poor Caroline! It nearly broke her

heart.

William was her idol she lived but for him now she seemed to be

replaced.

She moved away into a modest cottage of her own, resolved that she

would not be

an encumbrance to any one. She thought she was going into a decline,

and would

not live long anyway she was so pale and slight that Miss Burney said

it took

two of her to make a shadow. But we get a glimpse of

Caroline's energy when we find her writing home explaining how she had

just

painted her house, inside and out, with her own hands. Things are never so bad

as they

seem. It was not very long before William was sending for Caroline to

come and

help him out with his mathematical calculations. Later, when a fine boy

baby

arrived in the Herschel solar system, Caroline forgave all and came to

take

care of what she called "the Herschel planetoid." She loved this baby

as her own, and all the pent-up motherhood in her nature went out to

the little

"Sir John Herschel," the knighthood having been conferred on him by

Caroline before he was a month old. Mrs. Herschel was

beautiful and

amiable, and she and Caroline became genuine sisters in spirit. Each

had her

own work to do; they were not in competition save in their love for the

baby.

As the boy grew, Caroline took upon herself the task of teaching him

astronomy,

quite to the amusement of the father and mother. Fanny Burney now comes

with a

little flung-off nebula to the effect that "Herschel is quite the

happiest

man in the kingdom." There is a most charming little biography of

Caroline

Herschel, written by the good wife of Sir John Herschel, wherein some

very

gentle foibles are laid bare, and where at the same time tribute is

paid to a

great and beautiful spirit. The idea that Caroline was not going to

live long

after the marriage of her brother was "greatly exaggerated" she

lived to be ninety-eight, a century lacking two years! Her mind was

bright to

the last when ninety she sang at a concert given for the benefit of

an old

ladies' home. At ninety-six she danced a minuet with the King of

Prussia, and

requested that worthy not to introduce her as "the woman astronomer,

because, you know, I was only the assistant of my brother!" William

Herschel died in his eighty-fourth year, with his fame at full,

honored,

respected, beloved. Sir John Herschel, his

son, was

worthy to be called the son of his father. He was an active worker in

the field

of science a strong, yet gentle man, with no jealousy nor whim in his

nature.

"His life was full of the docility of a sage and the innocence of a

child." John Herschel died at

Collingwood, May Eleventh, Eighteen Hundred Seventy-one, and his dust

is now

resting in Westminster Abbey, close by the grave of England's famous

scholar,

Sir Isaac Newton. |