|

CHAPTER

XXIV

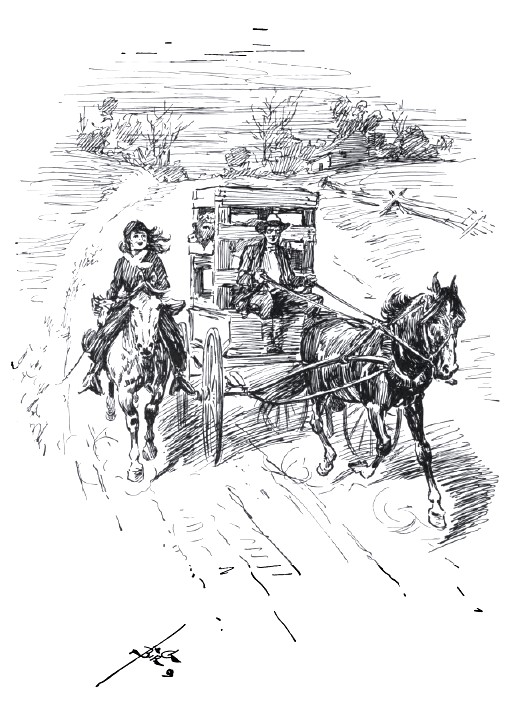

LOOKING BACKWARD SIX years have passed since I bought my farm, — years that have brought me hard work and but little more than a comfortable living in my profession. But the genuine pleasure I have experienced and the physical benefit I have derived from the cultivation of my tiny farm, have much more than repaid me for the many annoyances and losses in time and money my ill-directed but well-meant efforts have cost me. True, I have not arrived at that point where experienced farmers ask my advice in matters pertaining to the cultivation of the soil, the breeding of domestic animals, the relative advantage of top-dressing and sub-soiling, or other disputed questions in agricultural affairs. I have not even arrived at the distinguished honor of being a recognized contributor to an agricultural paper: my only contribution, which was written in a jocose spirit, was sent back with great promptness, with a note from the editor expressing an opinion decidedly adverse to the admission of the article on the ground that "The flippant and puerile spirit pervading the whole article does not accord with the dignity of the paper or the importance of the subject." But I have afforded amusement for my neighbors, my friends and the public generally by the variety of my experiences, and — Well, a person who creates amusement for the public is not wholly useless in this world, and so I feel that I have done something for others. Besides, there are many persons who have actually added materially to their income from my farming and gardening operations. I have bought cows and horses, hens and pigs, fertilizers and fruit trees, deodorizers and disinfectants, cedar posts and wire-netting, patent feeders and patent foods, and have, for each and every horse, hen, pig, bag, barrel, and other article, paid somewhat over the market price. I have exchanged, dickered, traded, bartered, and trafficked in these same articles, and have, I believe, invariably been worsted in these encounters; and so I feel that I have in a double measure been of benefit to my friends and acquaintances, by contributing liberally to the joy of the community and to its financial welfare. Now, what have I done for myself? I have to a great extent lost my irritability. I have opened a large house to my friends and guests, have had my table furnished with my own vegetables, eggs, milk, cream, and butter, and adorned from spring to fall with my own flowers. I have brought my farm to a high state of fertility, hardened my hands, strengthened my muscles, cured my indigestion, and benefited every member of my family, and I have never neglected in any way the duties of my profession. It is a gray afternoon near the end of November, and I am driving Polly hitched to a farm wagon. In the back of the wagon in a rack, straw-bedded, is a beautiful Jersey heifer. Behind, loping easily along, comes the little roan Indian pony, upon which, sitting easily on a cross saddle, is my once small daughter, now a girl of fourteen, riding with the ease and abandon of a cavalryman. The

roads are hard and smooth, the going excellent. Polly is

ambitious and spins along at a spanking pace, but cannot shake off

the smooth-gaited pony. A chill wind blows from the north, the dry

rushes at the river's edge bend and rustle eerily, a little gray bird

with jerking tail flies in and out of the dead bushes, while overhead

a single crow, black against the gray sky, wings its way toward a

growth of giant pines that shoulder to shoulder seem to defy the

coming assaults of the storm king.  Riding with the ease and abandon of a cavalryman As we pass the first bridge, down the steely course of the river comes a muffled figure, while the ring of the skates strikes sharply on the silent air. It is dusk as we whirl into the yard and pull our horses up, — dusk and chill with the cold breath of the dying year. Take our lantern and follow us as we unhitch Polly and lead her and the pony into the stable. As we enter, a pedigreed Jersey, from her warm and bedded stall, turns her head with its fringed ears and soft eyes, and lows comfortably. We blanket our horses, bed them deeply, then climb to the loft, where we throw down English hay, raised on my farm. The heifer, unbound and dragged to a well-bedded pen, stares about her in surprise at her comfortable quarters, then, pricking up her ears and elevating her tail, prances awkwardly. Our wagon is pulled into the carriage-house, the doors of the barn closed and locked, and we go next to the hen-coops. We carefully empty the water-cans, close the shutters to the windows, see that the ventilators are open and the fowls all at roost, and that none are sick, then pass on to another pen. In the little room at the entrance to the coop are many ribbons won at poultry shows, among them some blue ribbons. Then to the storehouse, where we see that the fastenings of the doors are firm. We cannot help flashing a lantern over the bins filled with apples, corn, cabbages, potatoes, turnips, and carrots, raised on our own place. As we come from the storehouse and fasten the door, night has fallen, the wind is moaning about the buildings, and a few flakes of snow, the advance-guard of the storm, come sifting silently down. We extinguish our lantern, and faintly in the gathering darkness we can make out the dead corn-stalks standing like ghosts of departed summer, while through the black mass of the clustered pines the wind moans drearily. Without all is cold and dark and dreary. Within all is bright and warm and comfortable. Summer is gone, but she will come again. Now for the winter and our fire and books. And locking arms with my daughter, I enter and shut out the gathering storm. |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2011

(Return to Web Text-ures)