| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XXIII

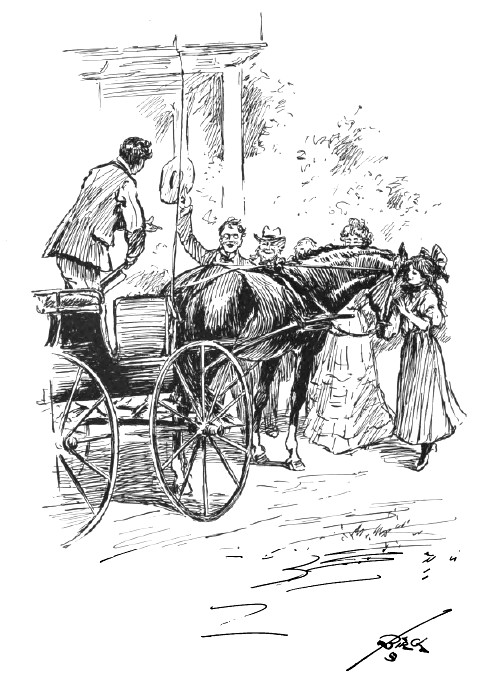

A RETURN IT was a beautiful afternoon in August about three years after I bought my farm, and I was sitting in my office idly watching the people passing in the square, and wondering why I did not hear from Dick, who was on a vacation and had not written me for ten days. I missed him and missed his letters, which were bright, gossipy, and full of happy observations on passing events. Dick had greatly disappointed me by firmly standing out against a college course, and by entering my office for the study of law. But in the office he was so apt and helpful, so good-natured and so studious, that I felt that perhaps he was right after all, and I had been looking forward to the day when his name might be on my sign, — so selfish do old men get when their interests are concerned. I felt reasonably sure about Dick. He was by no means a goody-goody, had a quick temper, was more than a bit mulish, but well-disposed and rather ambitious. He was well-liked by his acquaintances, and popular in a jovial, good-fellow-sort of way with the girls. While he had taken them to dances and entertainments, called on them, serenaded them with close-harmonied quartettes and glee-clubs, he had never shown any serious preference for any particular girl, and always when talking with me of his girl acquaintances had been frank and confidential. He was emphatically a boy to trust in such matters, and I felt very confident that he would never make a fool of himself over any girl or woman. On this day I was feeling remarkably at peace with the world. Business had been good, and fairly remunerative, the farm was prospering. I had eaten strawberries from my own patch until I could eat no more, raspberries and currants from my own bushes, all the early vegetables in season. My hens had laid wonderfully well, and the young cockerels were beginning to crow, my homing pigeons and black, smooth-legged tumblers had been prolific. In fact, a season of unprecedented peace and prosperity had enveloped my little farm as a garment. The afternoon mail came, and I lazily looked it over. There was little of importance save a letter from Dick. I put that aside for a moment while I dictated replies to the business letters, and then, while the click of the typewriter in the inner room disturbed the summer silence, I leaned back to enjoy Dick's letter, but promptly sat up with a jerk as I read this brief but astonishing message.

Aug. 6, 190- DEAR OLD MAN, — I have drawn on you for two hundred and fifty dollars. Please honor draft as I must have the money. Will explain everything when I get home which will be on Thursday next at about six o'clock. I am not coming alone, for I shall bring a young lady with me. You cannot help loving her as I do. Yours,

I looked out on the square without seeing anything. Then I took up the letter again; but the page shook so I couldn't read a word. I took a turn round the office, gulped down a glass of water, took a fierce grasp of myself, and this time read the letter through from date to signature. Then I sat in the window trying to realize it. Dick married! to a girl I had never seen, or heard of, and knew nothing about! Perhaps to a designing, elderly woman, possibly a widow, who knew how to marshal her attractions so as to bewilder and dazzle a boy of nineteen. What would become of his future, his law studies, his partnership with me, our joint productions in the way of briefs, declarations, rejoinders, sur rejoinders, rebutters, and sur-rebutters, our division of respectable if not fat fees, our enjoyment of an honorable and solid if not brilliant reputation as country attorneys, our joint productions as amateur agriculturists in the way of fruits, vegetables, staple products, and live-stock? What was to become of my ambition to retire one day from active work in office, court, farm, and garden, and to hand over the sceptre of authority to my son Dick? What was to become of — Oh, damn it all! hang all designing women, all languishing, ogling, curl-shaking, deceptive, false, dangerous widows! And Dick had done this! Dick! who had always been frank and square with me. Dick had married, a nobody, perhaps, a girl whom we might not be able to take to our hearts or our house. Why wasn't the law different? Why didn't we live in Germany or France or Russia or in some sensible country where boys of nineteen couldn't contract marriage without their parents' consent? Well, I must face it, we must all face it; I would pay the draft, but if Dick thought he was going to bring a squint-eyed Jezebel to my house for me to support; if Dick really expected to have me provide food, clothing and lodging for any gray-haired fairy he was ass enough to fall in love with; if Dick was banking on the probability that my wife and I would step down and out for the first female harpy that managed to get her veteran claws through his donkey's hide, — why, Dick would have a chance to learn something come Thursday evening at about six. No, he should not come home, danged if he should! I would write him at once. "Here! Miss Blank!" I yelled so loudly to my stenographer that, for the first time in her office-life perhaps, she came into my room without running her hand through her fluffy foretop or settling her belt. "Take this down at once! No, I'll write it myself." Where shall I address the idiot? Just like him; no address given, — letter posted in Boston. On his honeymoon in Boston, with my two hundred and fifty dollars. Well, he would find mighty little honeymoon after he got home with his superannuated old helpmeet. And I broke into such hearty maledictions that the stenographer tiptoed to her door and softly closed it. Then I went home with my letter and read it to my wife. She had recourse to tears, then reproaches, then hysterics. I thought I had carried on badly enough, but she showed me a few new things in that line. It was I who was to blame. It was I who had allowed him too much liberty. It was I who had sent him to that horrid summer resort, and had furnished him with money to spend on horrid old false-fronted widows. And did Dick think he was going to bring that woman home for her to work for? Well she guessed not! And did that woman think — Well, it is not advisable to disclose all she said. In view of later developments we both have reconsidered many conclusions that we arrived at that day, and have been truly sorry for some things we said; but allowing for the excitement under which we labored, and the sudden dashing of our hopes to the ground, some allowance should be made for us both. We were however firmly of the opinion that she was at least forty, wore a false front, rouge, pearl-powder, and high-heeled shoes, and laced to suffocation. It was thought best to acquaint Gramp and Dick's uncles and aunts with the circumstances, and they were nearly as much affected, and in somewhat the same way, as we were. His aunts wept bitterly, while his uncles, following Gramp's distinguished leadership, painted some of the most vivid word-pictures I ever saw or heard. I really was quite ashamed of my feeble efforts after hearing theirs. For the next few days I thought of the matter constantly. I slept badly and dreamed hideous dreams. My wife went about with red eyes and woe-begone countenance. My daughter was the only one who viewed the matter in the proper spirit. She looked at it with unjaundiced eyes, and looked forward with anticipation to a new sister. Indeed, after a few days I found myself wondering if I had not been a bit hasty. Perhaps after all she might not be so bad. Suppose she was young and pretty and dutiful? It wouldn't be at all bad. Suppose, after a time, a granddaughter or grandson arrived? Well, I always had loved my babies, and I guess I would make a pretty good grandpa after all, and Dick could have the large east front room for a sitting-room, and the small bedroom adjoining. I had practised law long enough to know the folly of anticipating a judgment. I was an ass, a venerable long-eared ass. I would venture to bet she was young and pretty. Dick was no fool. He may have been a bit imprudent, but who wanted an icicle for a son? I wouldn't give a cent for a boy who wouldn't be carried off his feet provided the right girl came along. I was wrong, I had been an ass. I guess it would be a good idea to paint and paper those rooms, and to get a new rug for the floor and a chiffonier with long, wide drawers. Women liked them, and I guess Dick's wife should have them if she wanted them. The best was none too good for Dick, and Dick's wife was going to be treated about as well as he. I saw a handsome fur rug that wouldn't look at all badly in front of their fireplace. Perhaps she had better choose these things. Yes, there was no doubt of it, —I would wait. But we would welcome her all the same, for she was Dick's wife. • • • • • • • • • • • It was Thursday afternoon, and we were waiting for Dick and his wife to arrive. I had shaved and put on my newly-pressed summer suit; my wife had on a white duck suit and white tennis shoes, my daughter wore the same. I sat under a tree reading a newspaper; a couple of law books lay opened at my feet. I hadn't read them, and didn't intend to read them, and didn't care a hang what they contained. Only it would be a good idea to let Dick's wife know just what sort of a family she was entering. If she was well-bred, she would feel more at home, and if she was ill-bred, forward, or conceited, it would perhaps be as well to impress her in the first place so as to keep her from undue self-assertiveness. As I sat there pretending to read, but in reality not seeing a line or a word of the page, I began again to be depressed about the prospect of an addition to the family that would at best be thoroughly unwelcome both to my wife and to me, and, more unfortunately, to Dick. A boy of his age would not be likely to be attracted by a young and refined girl, because Dick was certainly young, and for a boy, rather refined and fastidious, and he would be all the more liable to be impressed by the coarser and more mature charms of an altogether impossible person, only, alas! to find out his fatal mistake too late. It was only too true: Dick was an ass, and my first impressions were too likely to be true. Hang the women! hang 'em!! hang 'em!!! In spite of my disgust, anger, and deep depression, I could not restrain a smile as I suddenly beheld Gramp appear on his piazza across the street, got up as Gramp generally gets himself up on festal occasions, regardless, not of expense but of appearances. He had put on an old-fashioned black broadcloth coat with tails, — one of those perfectly dreadful coats that make a respectable man look like a composite picture of a pirate, a Methodist parson of the old school and a faro-dealer. He had neglected to change his trousers, and wore an old pair of an indescribable color, — a sort of greenish brown garnished with grease spots, — and ending in an old pair of shoes run down at the heel, cracked across the tops and sides, and gray with ashes. The costume, topped by a rusty black felt hat at a rakish angle on his snow-white hair, and further ornamented by a new clay pipe, made of the old gentleman a rather fierce but very fine-looking old chap. Beside him sat two of Dick's aunts, as usual, well and quietly dressed, and looking like thoroughbreds, all evidently conscious of the vital necessity of a first impression. None of the uncles were present, they having rather forcibly expressed their disgust with the whole proceedings. As it drew near six o'clock, I could sit still no longer and walked to the hedge and looked down the street. Suddenly, from the opposite direction, I heard the rapid thud of a horse's feet, — a quick short snappy trot that seemed strangely familiar. I turned and stared, and there whirled round the corner a sorrel mare with head up, mane and tail flying, going like the wind, and drawing a light buggy in which sat a young man grinning delightedly and holding the flying mare with the coachman's grip. Shades of immortal Cæsar! it was Dick driving Polly, — Polly for whom I had hunted so long and vainly! I was never so completely taken aback in my life, and stood blankly with my mouth open like a "plumb idjut." On the piazza my wife and daughter stood like people bereft of sense, until suddenly Nathalie's voice rang out: "Father! father! It's Polly! Dick's got Polly!" By this time Dick had pulled up, jumped to the ground, thrown the reins over Polly's back, and had come forward to greet us. "Well, old man," he said, "what do you think of my young lady?" "You infernal young rascal!" I sputtered; "I have been frightened into good behavior for a week. I thought you were married to a woman fifty years old and fat as a toad." And then we fell on him, and thumped and pump-handled him, and patted Polly, who was as glad to get back as we were to see her; and then we dragged Dick in to supper and demanded explanations instantly on penalty of life and limb, and without benefit of clergy. And Dick told how he had seen Polly one day pass through a suburb of Boston, and had followed on foot and by car, and had finally located her and had bought her after considerable dickering, for he soon found out that her unpleasant habit of halter-pulling had cheapened her considerably in the estimation of her owner. As to the buggy and harness he said he had always wanted a new buggy and harness, and he thought I would not mind if he bought them. Mind! the young scamp, — if he had known how much I really would have been willing to give to get him out of the scrape I fancied he was in, he could have stocked up with an automobile.  It's Polly, Dick's got Polly! |