| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER XII THE POTTERS OF BENNINGTON TO class Bennington pottery with Revere silver or Stiegel glass, or with the sgraffito and slip-decorated ware of the early Pennsylvania potters, would be to commit an anachronism, for the best of the Bennington ware was made but three score years ago. In the matter of genuine artistic merit, too, it suffers by comparison with some of the Other crafts. The fact remains, however, that its unique quaintness and comparative rarity have won for it, in the interest of collectors of Americana, a place beside the products of earlier craftsmen. As has been pointed out, the making of pottery and porcelain as an industrial art was not one of the first to be developed in this country. Much of the earlier product was plain, crude, and lacking in the elements of variety and charm that appeal to the collector. Comparatively speaking, Bennington ware is antique. The products of which we are speaking were made chiefly between 1847 and 1857, though the old pottery dates back half a century earlier. It was in 1793 that Capt. John Norton and his brother William moved from Sharon, Connecticut, where they had no doubt been engaged in making the coarse red earthenware famous in that section, and settled in Bennington, Vermont. Here they started an earthenware kiln, and in 1800 added the manufacture of stoneware. This pottery was conducted almost continuously by John Norton, who died in 1828, his son Luman, and his grandson Julius, until about 1846, when Julius Norton formed a new firm with Christopher Weber Fenton and Henry D. Hall. In the north wing of the old factory they began the manufacture of white and yellow crockery and Rockingham ware, the last being a yellow ware covered with a dark brown glaze, often mottled by spattering the glaze before firing. Most of the modeling was done by John Harrison, a potter who learned his trade in England. The mark on this ware was "Norton & Fenton," impressed. It is very rare but is occasion ally to be found. Though this pottery was in the hands of the Norton family exactly one hundred years, it was Fenton who was the soul of the enterprise, the craftsman of Bennington. He came to Bennington about 1840 and was taught the finer elements of the potter's trade by Luman Norton. It was to Fenton's skill, energy, and imagination, together with the discovery of fine kaolin clay and useful minerals in Vermont, that we are indebted for what we know as Bennington ware. About 1848 the partnership was dissolved and Fenton formed the firm of Lyman & Fenton with Alanson Lyman, a Bennington lawyer. A little later we find the firm name changed to Lyman, Fenton & Park. The new firm made white and yellow crockery, salt-glaze stoneware, Rockingham, and a thin, white porcelain called parian ware — the first to be manufactured in the United States. On a few pieces of parian the mark "Fenton's Works, Bennington, Vermont" appears in a rectangular border, which may indicate that Fenton was in business alone for a short time before the partnership was formed. In

1849 the firm was reorganized as the United States Pottery and a new

factory was erected across the river. The old Norton plant was

operated intermittently, making the plainer wares, until it was sold

out in 1893, having been once burned and rebuilt in the '50's.

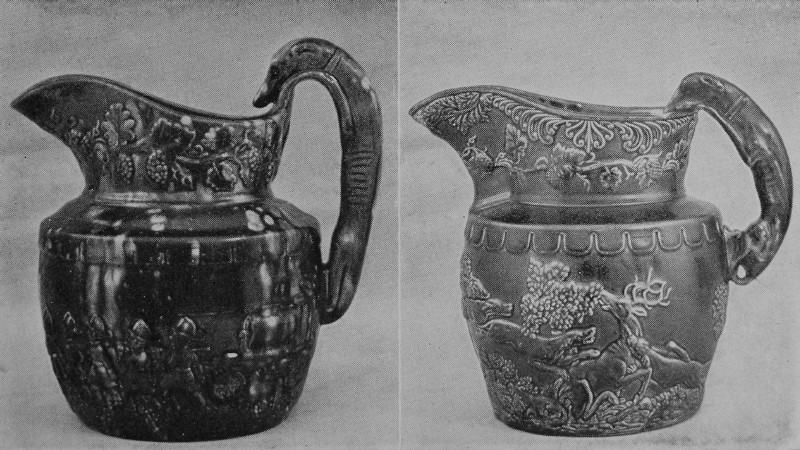

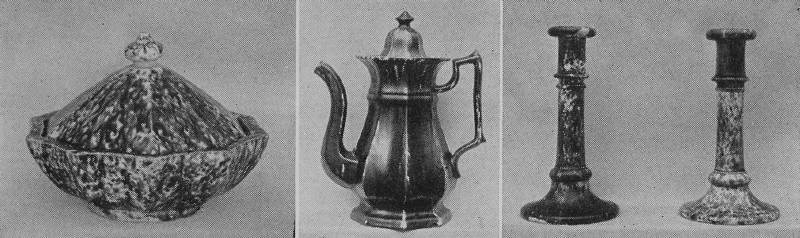

The United States Pottery at once undertook the production of the finer ornamental wares — Rocking ham, parian, white granite ware, and a little soft-paste porcelain. In 1849 Fenton took out a patent for the coloring of glazes and for a flint-enameled ware. This was an improvement on the Rocking ham and a product of great strength and variety of coloring. It included plain, mottled, and scroddled or striped ware, composed of different colored clays. The mark adopted about 1853 for the parian ware and porcelains consisted of a raised ribbon loop bearing the unpressed letters U S P and the number of the pattern. That on the new ware was composed of the following legend, impressed, in a large oval, often nearly obliterated by the glaze: "Lyman, Fenton & Co. Fenton's Enamel. Patented 1849. Bennington, Vt." Some later products of the concern bear a smaller oval mark and the words "United States Pottery Co. Bennington, Vt." The pottery's principal artists were Theophile Fry, who came from France or Belgium, and Daniel Greatbach, an Englishman. The latter, because he was responsible for some of the most popular designs, and because we are interested in craftsmen, deserves fuller mention. Daniel Greatbach came from a family of noted English potters and is said to have been at one time a modeler for the Ridgways in England. He came from Hanley, England, about 1839, and modeled some of the best wares produced at the famous potteries at Jersey City between 1839 and 1848. After that he was employed at various times in Peoria, Illinois, in Trenton, New Jersey, and in Bennington. In 1852 he established a pottery at South Amboy, New Jersey, in partnership with James Carr, but the enterprise failed. He was an artist, not a business man, and he died in poverty in Trenton. He was a remarkable character and endowed with great talent. He is described as a large, handsome man, always well dressed, and extremely courteous. Greatbach was the originator of many of the models most popular between 1840 and 1860 in this country. Some of those which he conceived in Jersey City he altered more or less and reproduced in Bennington. Notable among these was the hound-handled pitcher, which was made at Jersey City, at Bennington, and later, in inferior quality, at Trenton. This has given rise to some confusion among collectors. But the Bennington product was much the finest, and can be distinguished by the better modeling and by the space between the hound's nose and the edge of the pitcher. It is a shapely piece, a greyhound forming the handle and the body decorated with a hunting scene in relief. The Bennington model was produced soon after Greatbach arrived, in 1850, and was made in three sizes and in brown, blue, and green glazes — chiefly brown. In two or three years the new concern found itself in a flourishing condition with over a hundred hands employed. In 1853 the works were enlarged so that the factory was 160 feet long, and six improved kilns were erected. The machinery was run by water power. There were few china stores in those days and pottery goods had to be distributed largely by peddlers in both city and country. The company's selling headquarters were in Boston. For some reason the pottery's prosperity was comparatively short-lived, and by 1857 much of the manufacturing was discontinued. The plant was closed in 1858 and most of the potters moved away to Trenton, Ohio, and Illinois. In 1863 it was reopened long enough to make use of the materials stored there and then the books were closed for good. The buildings were torn down in 1870, and in 1873 most of the patterns were destroyed by fire. In 1858 Fenton moved to Peoria, Illinois, and in 1859 started a new pottery with Decius W. Clark, his former superintendent in Bennington. They commenced the manufacture of white granite and cream-colored wares, but the venture did not prove a success and was abandoned after about three years. Fenton

was born in Dorset, Vermont, in 1806 and learned the rudiments of his

trade in a common red-clay pottery at that place. For a decade he was

one of the foremost potters in the United States. He died in Joliet,

Illinois, November 7, 1865. His former partner, Alanson Lyman, died

in 1883, at the age of seventy-seven.

Collectors of Bennington ware have been, to a large extent, somewhat lacking in discrimination, valuing a brown pudding dish almost as highly as a finely modeled blue-and-white parian pitcher. The Rockingham and flint-enamel figures possess the quaintness that is the first attraction of Bennington ware, but the finer porcelains display more of those qualities of design and texture that ordinarily appeal to the connoisseur. It is well, therefore, to keep in mind the various kinds of china and pottery made at Bennington, and perhaps this can best be fixed by means of a recapitulation : 1846-1848. Norton & Fenton. white and yellow wares and Rockingham. 1848-1849. Fenton's works, Lyman & Fenton, and Lyman, Fenton & Park. Salt- glaze stoneware and parian added. 1849-1858.

United States Pottery. The above, and also white granite, variegated

and scroddled wares, While in many respects the Bennington figures owe much of their quaintness to a certain naïve crudity of design, they were far more carefully modeled than most of the products of other factories of the period and the glaze was more uniform, brilliant, and evenly applied, with a rich, velvety sheen. Moreover, it requires a certain sort of genius to design such fierce lions, such motherly cows, such jolly tobies. The range of coloring in the Rockingham and flint-enamel wares included olive, green, brown, yellow, and various mixtures. In the variegated pieces the mottling and scroddling was done with an evident effort at uniformity and evenness. Brown was the commonest color used, varying from a creamy tint to almost black. Some of the finest pieces are a deep, darkly shaded brown, slightly mottled, or in tortoise-shell effects, and bearing a hard, metallic luster. A mustard color is common, but the majority are a rich chocolate color. The parian ware was oftenest a grayish white like marble, occasionally cream, fawn-colored, or a delicate brown. On some pieces the decoration consisted of sharply raised figures in pure white on a pit ted blue ground of different shades. A descriptive list of all the models turned out by the United States Pottery would constitute a formidable catalogue. Table ware, toilet sets, mantel ornaments, toys, plain crockery of all sorts up to a half-bushel bowl, door plates, foot warmers, door knobs, curtain knobs, and a host of other articles would have to be included. For the present purpose it will be sufficient to mention a few of the pieces most interesting to collectors. In the Rockingham ware, pitchers, mantel ornaments, and flasks are most sought after. The ornaments include lions, dogs, deer, cows, particularly the recumbent cow, and toby jugs. A flask in the form of a book, bearing the title "Departed Spirits," is to be found in almost every collection. Rockingham candlesticks and even picture frames are occasionally to be found. The flint-enameled ware, usually plain brown or mottled, included ale jugs, jolly Dutchman and monk bottles, small figures, shovel-and-tongs rests, door plates, goblets and tumblers, goblet-shaped vases, milk and sap pans, pitchers, cuspidores, toby jugs and tobacco jars, bean pots, cracker jars, picture frames, candlesticks, book-shaped hot-water bottles, teapots, curtain knobs, toy banks in the form of grotesque heads, match safes, and a host of other forms. Popular among the figures were a lion with fore paw resting on a ball, a girl on horseback, and a poodle carrying a basket in his mouth. There were two slightly different forms of the jolly Dutchman or coachman bottle, about eleven inches high. The figure is of a man wrapped in a cloak, clutching a small mug, and wearing a high hat which forms the neck of the bottle. Another popular piece was a small creamer in the form of a smiling cow, which was also used as a mantel ornament. A lid on her back could be opened to admit the cream, which was poured out through her mouth. The pitchers alone offer a wide field for the collector. They were of all sizes, from small creamers to large cider jugs. There were various plain, fluted, octagonal, and decorated forms, the most famous and the most valuable to-day being Greatbach's hound-handled pitcher. The branch-handled and tulip designs are also in demand. The parian ware was more costly and was modeled with greater care. The vases and pitchers were particularly graceful in outline, more or less ornate, and light in weight. Some of the forms deserve a high rating as examples of the ceramic art. In this porcelain bisque were also made match holders, mustard cups, various dishes, cane handles, and mantel ornaments, including the figures of birds, swans, sheep, and children. The Bennington poodle, a sitting spaniel, and a cow were also made in parian, but are very rare, as are also the white toby and hound-handled pitcher. A famous piece was the large Niagara Falls pitcher, the pattern representing a cataract flowing over the sides to rocks beneath. Table and toilet services were extensively manufactured in white and marbled bodies, sometimes with a gold band. Utility wares were also made to a limited extent in green and cobalt blue glazed ware. Toilet sets, pitchers, and ornaments were made in white granite ware and porcelain decorated with gold and colored designs, the pitchers sometimes bearing the names or initials of the owners. Among the white granite ornaments were the swan, the cow creamer, and the figure of a little girl praying.

Bennington ware was originally moderate in price and considerable quantities of it were sold. Some of the finer parian pieces cost several dollars, but the small flint-enameled ornaments were peddled from door to door at fifteen to twenty-five cents apiece. There came a period, naturally enough, when Bennington ornaments began to look old-fashioned, and hundreds of them were doubtless thrown away. That fact and the natural tendency of pottery to get broken account for the comparative scarcity and high value of the ware to-day. A collection of Bennington ware was shown at the Pan-American Exposition in 1901, and since then it has steadily gained in popularity among collectors. It is now nearly as rare and as valuable as Lowestoft. An idea of the high prices that have occasionally been paid for coveted pieces may be gathered from the fact that at an auction sale in Boston in March, 1914, a pair of flint-enameled Bennington poodles brought $340. of course, that was exceptional, but the demand for Bennington ware has been extraordinary and the average dealer expects to get pretty high prices for authentic pieces. A great deal depends on the color, and, as a rule, dishes and utility wares are of less value than the figures. I have found the following prices quoted by dealers: $0 to $100 for a good lion; $25 to $50 for the dogs, cows, and deer; $75 to $150 for the white dogs; $25 to $0 for swans; hound-handled pitcher, $35 to $50; tulip pitcher, $30; other pitchers, $25 to $35; tobies, book bottles, monk and coachman bottles, etc., $15 to $25; candlesticks, $10 or $15 a pair; cow creamer, $10; small novelties, $5 to $8. The finer parian ware and the rarer pieces in green or blue glazes bring even higher prices. On the other hand most collectors have found it possible to pick up their specimens for much less, though the picking is by no means as easy as it was five years age. One such collector gave $1 and $2 respectively for two tobies; $5 for a coachman bottle; $5 for a book bottle; the same for a friar or monk bottle; $8 for a wash bowl and pitcher. The collector will do well not to be carried away by the high quotations of dealers, for the values are apt to be inflated, and while such prices are frequently obtained, they are really no fair indication of the real value of Bennington.

To strike a fair average, cows, deer, and dogs in good condition should be worth about $10; book bottles, $10; plain pitchers, dishes, etc., $5 to $7; coachman bottles, $12 to $15; hound-handled pitchers, $20; small novelties, $3 to $5; the finer parian, $25 to $50. Such pieces as the white dogs and the recumbent cow are becoming very rare and are likely to bring higher prices. Already

faking has been indulged in to some extent, the cow creamer having

been reproduced and Jersey City hound-handled pitchers having been

worked off as Bennington, but the collector is in little danger who

takes the trouble to become familiar with the modeling, coloring, and

general appearance of the true Bennington. |