|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER XVIII

THE FASTEST FLYERS CANADA GOOSE WILD DUCKS HERRING GULL CANADA GOOSE OF THE millions of migrants that stream , across the sky every spring and autumn, none attract so much attention as the wild geese. How their mellow honk, honk thrills one when the birds pass like ships in the night! Such big, strong, rapid flyers have little to fear in travelling by daylight too, but gunners have taught them the wisdom of keeping up so high that they look like mere specks. It must be a very dull child without imagination, who is not stirred by the flight of birds that are launched on a journey of at least two thousand miles. Don't you wish you were as familiar with the map as these migrants must be? Usually geese travel in a wedge-shaped flock, headed by some old, experienced leader; but sometimes, with their long necks outstretched, they follow one another in Indian file and shoot across the clouds as straight as an arrow. Geese spend much more time on land than ducks do. If you will study the habits of the common barnyard goose you will learn many of the ways of its wild relations that nest too far north to be watched by "every child." Canada geese that have been wounded by sportsmen in the fall, can be kept on a farm perfectly contented all winter; but when the honking flocks return from the south in March or April, they rarely resist " the call of the wild," and away they go toward their kin and freedom.

WILD DUCKS

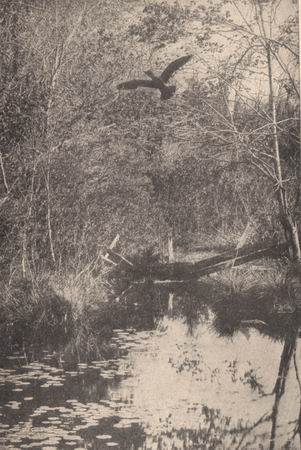

Birds that spend their summers for the most part north of the United States and travel past us faster than the fastest automobile racer or locomotive-and an hundred miles an hour is not an uncommon speed for ducks to fly-need have little to fear, you might suppose. But so mercilessly are they hunted whenever they stop to rest, that few birds are more timid. River and pond ducks, that have the most delicious flavour because they feed on wild rice, celery and other dainty fare, frequent sluggish streams and shallow ponds. There they tip up their bodies in a funny way to probe about the muddy bottoms, their heads stuck down under water, their tails and flat, webbed feet in the air directly above them, just as you have seen barnyard ducks stand on their heads. They like to dabble along the shores, too, and draw out roots, worms, seeds and tiny shellfish imbedded in the banks. Of course they get a good deal of mud in their mouths, but fortunately their broad, flat bills have strainers on the sides, and merely by shutting them tight, the mud and water are forced out of the gutters. After nightfall they seem especially active and noisy.  Black-crowned night heron rising from a morass  Canada geese In every slough where mallards, blue- and green-winged teal, widgeons, black duck and pintails settle down to rest in autumn, gunners wait concealed in the sedges. Decoying the sociable birds by means of painted wooden images of ducks floating on the water near the blind, they commence the slaughter at daybreak. But ducks are of all targets the most difficult, perhaps, for the tyro to hit. On the slightest alarm they bound from the water on whistling wings and are off at a speed that only the most expert shot overtakes. No self-respecting sportsman would touch the little wood duck-the most beautiful member of its family group. It is as choicely coloured and marked as the Chinese mandarin duck, and a possible possession for every one who has a country place with woods and water on it. Unlike its relatives, the wood duck nests in hollow trees and carries its babies to the water in its mouth as a cat carries its kittens. The large group of sea and bay ducks, contains the canvas-back, red-head and other vegetarian ducks, dear to the sportsman and epicure, These birds may, perhaps, be familiar to "every child " as they hang by the necks in butcher-shop windows, but rarely in life. Enormous flocks once descended upon the Chesapeake Bay region. To Virginia and Maryland, therefore, hastened all the gunners in the East until the canvas-back, at least, is even more rare in the sportsman's paradise than it is on the gourmand's plate. Every kind of duck is now served up as canvas-back. Some sea ducks, however, which are fish eaters, have flesh too tough, rank, and oily for the table. They dive for their food, often to a great depth, pursuing and catching fish under water like the saw-billed mergansers or shelldrakes which form a distinct group. The surf scoters, or black coots, so abundant off the Atlantic coast in winter, dive constantly to feed on mussels, clams or scallops. Naturally such athletic birds are very tough. With the exception of the wood duck, all ducks nest on the ground. Twigs, leaves and grasses form the rude cradle for the eggs, and, as a final touch of devotion, the mother bird plucks feathers from her own soft breast for the eggs to lie in. When there is any work to be done the selfish, dandified drakes go off by themselves, leaving the entire care of raising the family to their mates. Then they moult and sometimes lose so many feathers they are unable to fly. But by the time the ducklings are well grown and strong of wing, the drake joins the family, one flock joins another, and the ducks begin their long journey southward. But very few children, even in Canada, can ever hope to know them in their inaccessible swampy homes.

HERRING GULL

Called also: Winter Gull "Every child" who has crossed the ocean or even a New York ferry in winter, knows the big, pearly-gray and white gulls that come from northern nesting grounds in November, just before the ice locks their larder, to spend the winter about our open waterways. On the great lakes and the larger rivers and harbours along our coast, you may see the scattered flocks sailing about serenely on broad, strong wings, gliding and skimming and darting with a poetry of motion few birds can equal. There are at least three things one never tires of watching: the blaze of a wood fire, the breaking of waves on a beach, and the flight of a flock of gulls. Not many years ago gulls became alarmingly scarce. Why? Because silly girls and women, to follow fashion, trimmed their hats with gull's wings until hundreds of thousands of these birds and their exquisite little cousins, the terns or sea-swallows, had been slaughtered. Then some people said the massacre must stop and happily the law now says so too. Paid keepers patrol some of the islands where gulls and terns nest, which is the reason why you may see ashy-brown young gulls in almost every flock. When they mature, a deep-pearl mantle covers their backs and wings, and their breasts, heads and tails become snowy white. Their colouring now suggests fogs and white-capped waves. Why protect birds that are not fit for food and that kill no mice nor insects in the farmer's fields? is often asked. A wise man once said "the beautiful is as useful as the useful," but the picturesque gulls are not preserved merely to enliven marine pictures and to please the eye of travellers. They fill the valuable office of scavengers of the sea. Lobsters and crabs, among many other creatures under the ocean, gulls, terns and petrels, among many creatures over it, do for the water what the turkey buzzard does for the land-rid it of enormous quantities of refuse. When one watches hundreds of gulls following the garbage scows out of New York harbour, or sailing in the wake of an ocean liner a thousand miles or more away from land, to pick up the refuse thrown overboard from the ship's kitchen, one realises the excellence of Dame Nature's housecleaning.  The feather-lined nest of a wild duck [IMAGE] Sea gulls in the wake of a garbage scow cleansing New York harbour of floating refuse Gulls are greedy creatures. No sooner will one member of a flock swoop down upon a morsel of food, than a horde of hungry companions, in hot pursuit, chase after him to try to frighten him into dropping his dinner. With a harsh, laughing cry, akak, kak, akak, kak, kak, they wheel and float about a feeding ground for hours at a time. And they fly incredibly far and fast. A flock that has followed an ocean greyhound all day will settle down to sleep at night "bedded" on the rolling water like ducks while "rocked in the cradle of the deep." After a rest that may last till dawn, they rise refreshed, fly in the direction of the vanished steamer and actually overtake it with apparent ease in time to pick up the scraps from the breakfast table. Reliable sailors say the same birds follow a ship from our shores all the way across the Atlantic. THE END

|