|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER XVII

BIRDS OF THE SHORE AND MARSHES KILLDEER SEMIPALMATED OR RING-NECKED PLOVER LEAST SANDPIPER SPOTTED SANDPIPER WOODCOCK CLAPPER RAIL SORA RAIL GREAT BLUE HERON LITTLE GREEN HERON BLACK-CROWNED NIGHT HERON AMERICAN BITTERN KILLDEER IF YOU don't know the little killdeer plover, it is surely not his fault, for he is a noisy sentinel, always ready, night or day, to tell you his name. Killdee, killdee, he calls with his high voice when alarmed-and he is usually beset by fears, real or imaginary-but when at peace, his voice is sweet and low. Much persecution from gunners has made the naturally gentle birds of the shore and marshes rather shy and wild. Most plovers nest in the Arctic regions, where man and his wicked ways are unknown. When the young birds reach our land of liberty and receive a welcome of hot shot, the survivors learn their first lesson in shyness. Some killdeer, however, are hatched in the United States. No sportsman worthy the name would waste shot on a bird not larger than a robin; one, moreover, with musky flesh; yet I have seen scores of killdeer strung over the backs of gunners in tide-water Virginia. Their larger cousins, the black-breasted, the piping, the golden and Wilson's plovers, who travel from the tundras of the far North to South America and back again every year, have now become rare because too much cooked along their long route. You can usually tell a flock of plovers in flight by the crescent shape of the rapidly moving mass. With a busy company of friends, the killdeer haunts broad tracts of grassy land, near water, uplands or lowlands, or marshy meadows beside the sea. Scattered over a chosen feeding ground, the plovers run about nimbly, nervously, looking for trouble as well as food. Because worms, which are their favourite supper, come out of the ground at nightfall, the birds are especially active then. Grasshoppers, crickets, and other insects content them during the day.

SEMIPALMATED PLOVER

The killdeer, which is our commonest plover, has a little cousin scarcely larger than an English sparrow that is a miniature of himself, except that the semipalmated (half-webbed) or ring-necked plover has only one dark band across the upper part of his white breast, while the killdeer wears two black rings. This dainty little beach bird has brownish-gray upper parts so like the colour of wet sand, that, as he runs along over it, just in advance of the frothing ripples, he is in perfect harmony with his surroundings. Relying upon that fact for protection, he will squat behind a tuft of beach grass if you pass too near rather than risk flight. When the tide is out, you may see the tiny forms of these common ring-necks mingled with the ever-friendly little sandpipers on the exposed sand bars and wide beaches where all keep up a constant hunt for bits of shell fish, fish eggs and sand worms. General Greely found them nesting in Grinnell Land in July, the males doing most of the incubating as is customary in the plover family, whose females certainly have advanced ideas. Downy little chicks run about as soon after leaving the egg as they are dry. In August the advance guard of southbound flocks begin to arrive in the United States en route for Brazil-quite a journey in the world to test the fledgling's wings.

LEAST SANDPIPER

Almost every child I know is more familiar with Celia Thaxter's poem about the little sandpiper than with the bird itself. But if you have the good fortune to be at the seashore in the late summer, when flocks of the friendly mites come to visit us from the Arctic regions on their way south, you can scarcely fail to become acquainted with the companion of Mrs. Thaxter's lonely walks along the beach at the Isles of Shoals where her father kept the lighthouse The least sandpipers, peeps, ox-eyes or stints, as they are variously called, are only about the size of sparrows-too small for any self-respecting gunner to bag, therefore they are still abundant. Their light, dingy-brown and gray, finely speckled backs are about the colour of the mottled sand they run over so nimbly, and their breasts are as white as the froth of the waves that almost never touch them. Beach birds become marvellously quick in reckoning the fraction of a second when they must run from under the combing wave about to break over their little heads. Plovers rely on their fleet feet to escape a wetting. Least sandpipers usually fly upward and onward if a deluge threatens; but they have a cousin, the semipalmated (half-webbed) sandpiper that swims well when the unexpected water suddenly lifts it off its feet. These busy, cheerful, sprightly little peepers are always ready to welcome to their flocks other birds-ring-necked plovers, turnstones, snipe and phalaropes. If by no other sign, you may distinguish sandpipers by their constant call, peep-peep.

SPOTTED SANDPIPER

Do you know the spotted sandpiper, teeter, tilt-up, teeter-tail, teeter-snipe, or tip-up, whichever you may choose to call it? As if it had not yet decided whether to be a beach bird or a woodland dweller, a wader or a perching songster, it is equally at home along the seashore or on wooded uplands, wherever ditches, pools, streams, creeks, swamps, and wet meadows furnish its favourite foods. It stays with us through the long summer. Did you ever see it go through any of the queer motions that have earned for it so many names? Jerking up first its head, then its tail, it walks with a funny, bobbing, tipping, see-saw gait, as if it were self-conscious and conceited. Still another popular name was given from its sharp call peet-weet, peet-weet, rapidly repeated, and usually uttered as the bird flies in graceful curves over the water or inland fields.

WOODCOCK

Called also: Blind, Wall-eyed, Mud, Bigheaded, Wood, and Whistling Snipe; Bog-sucker; Bog-bird; Timber Doodle Whenever you see little groups of clean-cut holes dotted over the earth in low, wet ground, you may know that either the woodcock or Wilson's snipe has been there probing for worms. Not even the woodpecker's combination tool is more wonderfully adapted to its work than the bill of these snipe, which is a long, straight boring instrument, its upper half fitted with a flexible tip for hooking the worm out of its hole as you would lift a string out of a jar on your hooked finger. Down goes the bill into the mud, sunk to the nostrils; then the upper tip feels around for its slippery victim. You need scarcely hope to see the probing performance because earth-worms, like mice, come out of their holes after dark, which is why snipe are most active then. A little boy once asked me this conundrum of his own making: "What is the difference between Martin Luther and a woodcock?" Just a few differences suggested themselves, but I did not guess right the very first time; can you? "One didn't like a Diet of Worms and the other does," was the small boy's answer. After the ground freezes hard in the northern United States and Canada, the woodcock is compelled to go south to Virginia. But by the time the skunk cabbage and bright-green, fluted leaves of hellebore are pushing through the bogs and wet woodlands in earliest spring, back he comes again. An odd-looking, thick necked, chunky fellow he is, less than a foot in length, his long, straight, stout bill sticking far out from his triangular head; his eyes placed to far back in the upper corners that he must be able to see behind him quite as well as he can look ahead; the streaks and bars of his mottled russet-brown, gray and buff and black upper parts being so laid on that he is in perfect harmony with the russet leaves, earth and underbrush of his woodland home. When his mate is sitting on her nest, the mimicry of her surroundings is so perfect it is well-nigh impossible to find her. Sportsmen pursue both the woodcock and Wilson's snipe relentlessly, but happily they are no easy targets. Rising on short, stiff, whistling wings they fly in a zig-zag, erratic flight, and quickly drop to cover again, continually breaking the scent for a pursuing dog.

RAILS

Rails are such shy, skulking hiders among the tall marsh grasses that "every child" need never hope to know them all; but a few members of the family that are both abundant and noisy, may be readily recognised by their voices alone. All rails prefer to escape from an intruder through the sedges in well-worn runways rather than trust their short, rounded wings to bear them beyond danger; and for forcing their way through grassy jungles, their narrow-breasted, wedge-shaped bodies are perfectly adapted. Compressed almost to a point in front, but broad and blunt behind where their queer little short-pointed tails stand up, the rails' small figures thread their way in and out of the mazes over the oozy ground with wonderful rapidity. "As thin as a rail" means much to the cook who plucks one. It offers even a smaller bite than a robin to the epicure. When a gunner routs a rail it reluctantly rises a few feet above the grasses, flies with much fluttering, trailing its legs after it, but quickly sinks in the sedges again. Except in game bags, you rarely see a rail's varied brown and gray back or its barred breast. The bill is longer than the head. The long, widespread, flat toes help the owner to tread a dinner out of the mud as well as to swim across an inlet; and the short hind toes enable him to cling when he runs up the rushes to reach the tassels of grain at the top. No doubt you once played with some mechanical toy that made a noise something like the peculiar, rolling cackle of the clapper rail. This "marsh hen," which is common in the salt meadows along our coast from Long Island southward, continually betrays itself by its voice; otherwise you might never suspect its presence unless you are in the habit of pushing a punt up a creek to get acquainted with the interesting shy creatures that dwell in what Thoreau called "Nature's sanctuary." The clapper's cousin, the sora, or Carolina rail, so well known to gunners, alas! if not to "every child," delights to live wherever wild rice grows along inland lakes and rivers or along the coast. Its sweetly whistled spring song ker-wee, ker-wee, and "rolling whinny" give place in autumn to the 'kuk, kuk, 'k-'k-'k'kuk imitated by alleged sportsmen in search of a mere trifle of flesh that they fill with shot. As Mrs. Wright says of the bobolinks (neighbours of the soras in the rice fields) so may it be written of them; they only serve "to lengthen some weary dinner where a collection of animal and vegetable bric-a-brac takes the place of satisfactory nourishment."

GREAT BLUE HERON

Standing motionless as the sphinx, with his neck drawn in until his crested head rests between his angular shoulders, the big, long-legged, bluish-gray heron depends upon his stillness and protective colouring to escape the notice of his prey, and of his human foes (for he has no others). In spite of his size-and he stands four feet high without stockings-it takes the sharpest eyes to detect him as he waits in some shallow pool among the sedges along the creek or river side, silently, solemnly, hour after hour, for a little fish, frog, lizard, snake, or some large insect to come within striking distance. With a sudden stroke of his long, strong, sharp bill, he either snaps up his victim, or runs it through. A fish will be tossed in the air before being swallowed, head downward, that the fins may not scratch his very long, slender throat. When you are eating ice cream, don't you wish your throat were as long as this heron's? A gunner, who wantonly shoots at any living target, will usually try to excuse himself for striking down this stately, picturesque bird into a useless mass of flesh and feathers, by saying that herons help themselves to too many fish. (He forgets about all the mice and reptiles they destroy.) But perhaps birds, as well as men, are entitled to a fair share of the good things of the Creator. Some people would prefer the sight of this majestic bird to the small, worthless fish he eats. What do you think about protecting him by law? Any one may shoot him now. The broad side of a barn would be about as good a test of a marksman's skill. The evil that birds do surely lives after them; the good they do for us is fax too little appreciated. Almost the last snowy heron and the last egret of Southern swamps have yielded their bodies to the knife of the plume hunter, who cuts out the exquisite decorations these birds wear during the nesting season. Inasmuch as all the heron babies depend upon their parents through an unusually long, helpless infancy, the little orphans are left to die by starvation. For what end is the slaughter of the innocents? Merely that the unthinking heads of vain women may be decked out with aigrettes! Don't blame the poor hunters too much when the plumes are worth their weight in gold.

LITTLE GREEN HERON

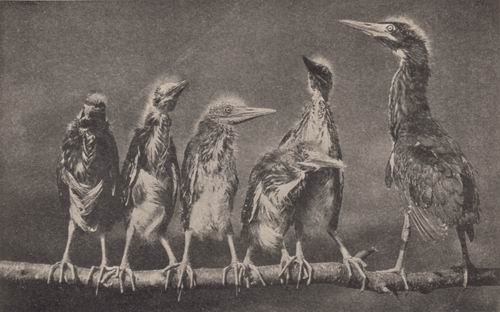

Called also: Poke; Chuckle-head This most abundant member of his tropical tribe that spends the summer with us, is a shy, solitary bird of the swamps where you would lose your rubber boots in the quagmire if you attempted to know him too intimately. But you may catch a glimpse of him as he wades about the edge of a pond or creek with slow, calculated steps, looking for his supper. All herons become more active toward evening because their prey does. By day, this heron, like his big, blue cousin, might be mistaken for a stump or snag among the sedges and bushes by the waterside, so dark and still is he. Herons are accused of the tropical vice of laziness; but surely a bird that travels from northern Canada to the tropics and back again every year to earn its living, as the little green heron does, is not altogether lazy. Startle him, and he springs into the air with a loud squawk, flapping his broad wings and trailing his greenish-yellow legs behind him, like the storks you see painted on Japanese fans.  A flock of friendly sandpipers and turnstones in wading  One little sandpiper  The coot He and his mate have long, dark-green crests on their odd-shaped, receding heads and some lengthened, pointed feathers between the shoulders of their green or grayish-green hunched backs. Their figures are rather queer. The reddish-chestnut colour on their necks fades into the brownish-ash of their under parts, divided by a line of dark spots on the white throat that widen on the breast. Although the little green heron is the smallest member of this tribe of large birds that we see in the Northern States and Canada, it is ,,.bout a foot and a half long, larger than any bird, except one of its own cousins, that you are likely to see in its marshy haunts. Unlike many of their kind a pair of these herons prefer to build their rickety nests apart by themselves rather in one of those large, sociable, noisy and noisome colonies which we associate with the heron tribe. Flocking is sometimes a fatal habit.  The little green heron: the smallest and most abundant member of his tribe  Half grown little green herons on dress parade BLACK-CROWNED NIGHT HERON Called also: Quawk; Qua Bird When the night herons return to us from the South in April, they go straight to the home of their ancestors, to which they are devotedly attached-rickety, ramshackle heronries, mere bundles of sticks in the tops of trees in some swamp-and begin at once to repair them. The cuckoo's and the dove's nests are fine pieces of architecture compared with a heron's. Is it not a wonder that the helpless heron babies do not tumble through the loose twigs? When they are old enough to climb around their latticed nursery, they still make no attempt to leave it, and several more weeks must pass before they attempt to fly. If there is an ancient heronry in your neighbourhood, as there is in mine, don't attempt to visit the untidy, ill-smelling place on a hot day. One would like to spray the entire colony with a deodoriser. Thanks to the night heron's habits that keep him concealed by day when gunners are abroad, a few large heronries still exist within an hour's ride of New York, in spite of much persecution. Unlike the solitary little green cousin, the black-crowned heron delights in company, and a hundred noisy pairs may choose to nest in some favourite spot. How they squawk over their petty quarrels! Wilson likened the noise to that of "two or three hundred Indians choking one another." Only when they have young fledglings to feed do these herons hunt for food in broad daylight. But as the light fades they become increasingly active and noisy; even after it is pitch dark, when the fishermen go eeling, you may hear them quawking continually as they fly up and down the creek. Big, pearly-gray birds (they stand fully two feet high) with black-crowned heads, from which their long, narrow, white wedding feathers fall over the black top of the back, the night herons so harmonise with the twilight as to seem a part of it.

AMERICAN BITTERN

Called also: Stake-driver; Poke; Freckled Heron; Booming Bittern; Indian Hen Even if you have never seen this shy hermit of large swamps and marshy meadows you must know him by his remarkable "barbaric yawp." Not a muscle does this brown and blackish and buff freckled fellow move as he stands waiting for prey to come within striking distance of what appears to be a dead stump. Sometimes he stands with his head drawn in until it rests on his back; or, he may hold his head erect and pointed upward when he looks like a sharp snag. While he meditates pleasantly on the flavour of a coming dinner, he suddenly snaps and gulps, filling his lungs with air, then loudly bellows forth the most unmusical bird cry you are ever likely to hear: You may recognise it across the marsh half a mile away or more. A nauseated child would go through no more convulsive gestures than this happy hermit makes every time he lifts up his voice to call, pump-er-lunk, pump-er-lunk, pump-er-lunk. Still another noise has earned him one of his many popular names because it sounds like a stake being driven into the mud. A booming bittern I know sits hour after hour, almost every day in summer, year after year, on a dark, decaying pile of an old dock in the creek. Our canoe glides over the water so silently it rarely disturbs him. The timid bird relies on his protective colouring to conceal him in so exposed a place and profits by his fearlessness in broad daylight next to an excellent feeding ground. At low tide he walks about sedately on the muddy flats treading out a dinner. Kingfishers rattle up and down the creek, cackling rails hide in the sedges behind it, red-winged blackbirds flute above the phalanxes of rushes on its banks: but the bittern makes more noise, especially toward evening, than all the other inhabitants of the swampy meadows except the frogs, whose voices he forever silences when he can. Frogs, legs and all, are his favourite delicacy. |