CHAPTER III.

DR.

COOK'S OWN STORY.

When

Dr. Cook reached Copenhagen he gave a picturesque and detailed

account of his travels. In fact, he gave it many times, such was the

mad eagerness of learned men and laymen, of kings and men of humble

position, to know all that he had seen and to drink in the wonders of

the North. Cook was like one of the travelers of old who, returning

from a far country to their homes, were beseiged by their friends and

were wont to sit for hours in the great hall of a castle, telling and

retelling the marvels that had befallen.

Perhaps

the best account Cook gave of his dash to the pole was given to W. T.

Stead, the noted London editor and publisher. Stead passed some hours

with Cook and this was what he heard:

"Warning

my Eskimos that only unyielding determination and patience could take

us through the fight against famine and frost and that my success

depended as much upon their loyalty to me as upon myself. I started

for the North Pole on the morning of February 19, with ten men and

103 dogs drawing eleven heavily loaded sledges. Overcoming the

reluctance of my Eskimos to leave the mainland of Greenland by

argument that I would discover new hunting for them across the sound

I marched my party out onto the quivering ice of Smith Sound. We

marched in the dark, the daylight of the Arctic winter's end being

limited to but a few hours. Gloom unrelieved even by the Aurora

surrounded us. Progress was of necessity slow, the piled up ice

forming veritable mountains in our path, over which we had in many

instances to drag dogs and sleighs. The thermometer as we crossed the

sound dropped to 83 degrees below zero, Fahrenheit. On the heights of

Ellesmere Sound we suffered our first losses, several of our dogs

being frozen.

"Game

trails helped us along through Nansen's Sound to the Land's End. Musk

oxen, Arctic hare and polar bears, which were comparatively

plentiful, supplied us with food. It was, of course, necessary to eat

raw meat as our supply of alcohol, the only fuel we carried, was

being kept for extreme emergency. From Land's End we pushed out into

the polar sea on our battle against shifting ice to reach the

southern point of Heilberg Island.

"Here

I established the base for my final effort, selecting the two best

men in my party, Ahweish and Stuckshook, with twenty-six of my

strongest dogs.

"Before

me lay 460 miles of frozen waste broken by ice mountains devoid as

far as we knew of game or anything to sustain life. On our sleds were

supplies sufficient to last us with rigid economy just the distance

we had to traverse and return and no farther. Added to the gloom of

the Arctic night was an overcast sky, making accurate observation for

several days next to impossible. Onward we went, marching along the

level ice, scrambling, pushing, pulling, fighting over the ice hills.

The motion of floating ice could be felt distinctly and served to

frighten my two Eskimos who, however, after a few days' experience

learned to disregard the possible danger of a breakup in open water.

"Straight

on we went, guided mainly by compass, pressure of time and fear of

exhausting supplies, rendering anything like accurate study of

surrounding conditions impossible. On March 30 the atmosphere cleared

a trifle, enabling me to make my first accurate observation, which

showed that we were at latitude 84 degrees 0 minutes 47 seconds and

longitude 86 degrees o minutes 36 seconds. Here I found the last

signs of solid earth. Before us was a moving sea of ice, devoid of

everything living, every trace of anything animal. Neither footprints

of bears, blowholes of seals, nor even traces of the microscope

creatures of the deep could be detected.

"As

we progressed the monotony of the ever moving sea of ice became

almost unbearable. But cold, merciless, penetrating cold, more even

than the object before us, drove us to almost frenzied effort to lay

that sea behind us. Forward we went, lash of duty and merciless drive

of extreme cold spurring us. So day by day we laid off the distance,

dogs and men standing the strain with marvelous fortitude.

"Our

first real glimpse of the sun we obtained on the night of April 7,

when it swung out over the northern ice. Added to our hardships was

the glare of the snow which rendered us almost snow-blind at times.

Sunburn and frostbite attacked us on the same day; dogs were becoming

emaciated from the long march and savage; the patience of my Eskimos

even was beginning to give way under the strain of that daily fight

against the merciless, silent, grim ice. Weary legs scantily rested

by the night's rest were yet eagerly spread over the distance to be

marched for the day, the one impulse of my men apparently being to

conquer and return. On April 8 my observations showed us to be at

latitude 86 degrees 0 minutes 36 seconds, longitude 94 degrees 0

minutes 2 seconds. Less than 100 miles in nine days.

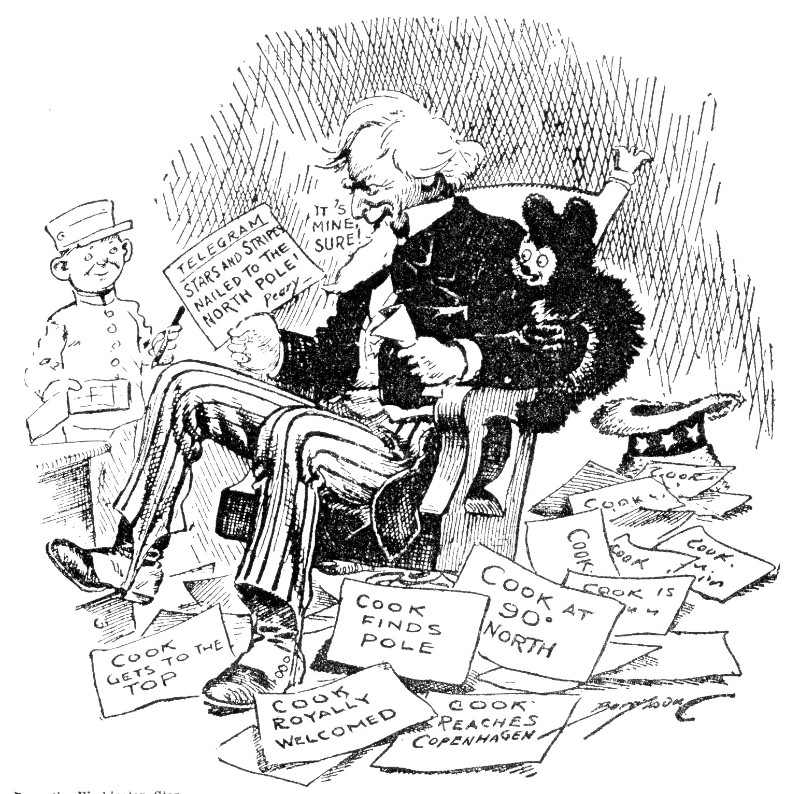

From the Washington Star

"Circuitous

twists around ice hills too high to be conquered, troublesome

pressure lines and old ice dangerous to our dogs and the men

themselves forced us to lose much valuable time.

"Hasty

stock-taking convinced me that we must push forward and make our

distance within fourteen days or return with our goal unconquered.

Eastward the ice drift began to take us rapidly and with force that

caused me the greatest anxiety. Still 200 miles from the pole and

fourteen days the absolute limit in which to conquer that distance.

But from here on our troubles began to diminish.

"The

ice fields became more regular. Fewer crevices, with little crushed

or old ice, made our progress astonishingly rapid. From the

eighty-seventh to the eighty-eighth latitude, much to our surprise,

we found signs of land. Positive evidence, however, was lacking. In

fact, I knew not whether we were marching on land or sea.

"On

the 14th I took another observation. Our position was shown as

latitude 88 degrees 21 minutes and longitude 95 degrees 52 minutes.

Less than 100 miles from the goal. Again the over-weary dogs were

lashed into action. Once more our weary legs took up the march. Less

than 100 miles to go, and still a quick calculation showed me enough

provisions if we did it in six days.

"Our

speed became a veritable race. The time was at hand for the last

mustering of every energy. The goal was too near to be lost now. Snow

shelters we gave up. We were too weary at the end of our marches to

erect them. Huddled together, our dogs the same, we rested when weary

and marched whenever possible. We tried our silk tent and found it

served to shelter us perceptibly from the bitter cold. I imagined

that I saw signs of land every day, but could not trust my senses

under the strain. Onward we pushed, our horizon ever monotonous,

uncrossed now by cloud or indeed anything. Mirages when the sun shone

turned the world topsy-turvy. Observations were made at every step to

guide us accurately.

"Steadily

the ice improved until we appeared to be moving almost on a level

glacial sea. Slower, despite frantic effort and ever growing

impatience, our pace again became. The terrific speed of the past

hours I saw clearly could not be maintained, but to try to stop my

men appeared to be useless. Rest had become a farce to us. Even the

dogs appeared impatient at the enforced stops. April 21 I stopped the

party and prepared to take an observation. Rough calculation told me

that I must be somewhere in the vicinity of the point I was seeking.

I found that our latitude was 89 degrees 57 minutes 46 seconds. The

North Pole was within sight!

"Fourteen

seconds more we advanced slowly, almost painfully. The anxiety was

terrible. Again, to make sure, I took an observation by the sun. It

was correct. Our latitude was exactly 89 degrees 58 minutes. Forward

again we went, taking observations every few seconds. Finally we

stopped. I believed I had reached the goal. Again, almost

tremblingly, I took an observation. There was no mistake. A series of

circular observations around the place where we temporarily halted

proved me to be at the point.

"The

North Pole was conquered!

"Conquered

and in the nick of time, for our provisions even at the most

economical calculation could not have lasted us had the northern

march taken three days more. Forty-eight hours we remained in the

vicinity of the lonely, cheerless spot, the goal of the explorers'

ambition for centuries. I rested the men and dogs as much as possible

in the dreary, chilly waste. Rest for me was impossible. The

knowledge of the final conquest kept me in almost constant activity.

April 23 I ordered the return.

"Our

return journey, although marked by more hardship than our advance to

the North, was nevertheless made lighter by the joy of duty

accomplished. Although we were forced to kill several of our dogs for

food and finally allowed those still living to run loose at the spot

where we crossed the Firth of Devon into Jones Sound, we took our

misfortunes more or less cheerfully and at Cape Sparbo, which we

reached in September, we built an underground den and remained there

until the sunrise of 1909, living on game killed with crude

instruments and waiting patiently until the new day could take us

back to tell the world of our triumph.

"February

18 the new start was made for Annootok. April 15 we reached the

Greenland shores again. The rest the world knows."

Mr.

Stead adds by way of comment:

"In

surveying Dr. Cook's story it will be well to remember that all the

hardships, the hair-breadth escapes, all the famine and the imminent

prospects of death occurred not in the rush to the pole but on his

return journey, especially in the last six months of his journeying.

"Public

attention has been riveted upon his dash to the pole across the

frozen Polar Sea. But that was with him, as with Peary, a

comparatively swift, uneventful advance, kept up day after day at the

rate of fifteen miles daily.

"If

the western drift of ice had not carried him out of reach of the game

lands at Herbert Island he would in all probability have been back

twelve months earlier. The real hardships of Dr. Cook began not in

high, but comparatively low latitudes.

"He

has a far vivider recollection of the stirring events occurring last

winter than of the comparatively monotonous rush to the pole. He sees

this polar journey at the end of a long vista of fifteen months,

which were crowded with such stirring episodes, filled with such

wearing exertion that — as he told me — it seemed as though all

the cells of his body and brain were burned out and replaced in the

fire of that strenuous life.

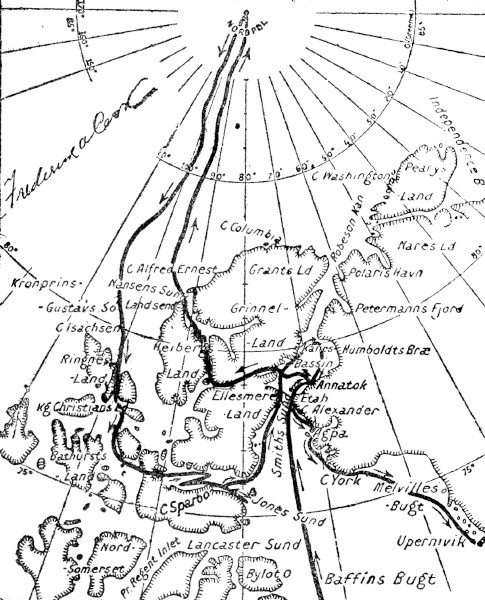

Click Map for Larger Image

MAP DRAWN AND SIGNED BY DR. COOK, SHOWING HIS ROUTE TO AND

FROM

THE NORTH POLE. HIS AUTOGRAPH APPEARS IN THE UPPER LEFT CORNER.

"One

thing stands out conspicuous — that this American citizen never

discredited his country by any high falutin vulgarity or ungenerous

caviling against any brother explorer.

He

impressed every one, from the King of Denmark down, as a

simpleminded, honest man, not a bit of a bounder. I believe him to be

absolutely unprovided by nature with the necessary outfit of a fakir.

"Cook

himself is certain that he got to the pole. He has a certainty that

is as calm, as immutable, as the great pyramids."

A

DIPLOMAT'S TRIBUTE TO DR. COOK.

Dr.

Maurice Francis Egan, American Minister to Denmark, in a magazine

article written shortly after Dr. Cook's return to the United States,

tells in a straightforward way why he believes implicitly in Dr.

Cook, and narrates interestingly some of his experiences with Dr.

Cook in Copenhagen immediately following the explorer's return from

the North Pole.

Dr.

Egan had been prepared for the complete acceptance of Dr. Cook's

story, which he now expresses, by the attitude of the Danes

themselves, who relied upon the testimony of those who vouched for

the intrepid traveler as much as upon his own, in view of their

especial qualification for judging the veracity of anything that

comes out of the frozen North. In the course of his introduction,

leading up to the receipt in Copenhagen of the two cablegrams

announcing Dr. Cook's discovery, Dr. Egan says:

"The

people of Scandinavia are natural explorers. One cannot teach an Arab

anything about the desert, and it would be a very audacious man who

from southern regions would attempt to give lessons to a Dane or a

Norwegian on the lands that lie above him or seas that lie beyond

him. These people know by the instinct of long heredity, by constant

study of the maps of Greenland and of the unknown lands of the waters

that are lost in mist, the ways of the frozen North. They know the

ins and outs of Arctic warfare as we know the character of the

various States in our Union. To a Dane, Greenland, Iceland and the

land which Cook has seen are subjects of perpetual interest. They are

always looking toward the North, and expecting news from the

mysterious North, and the sojourner among these people so learns to

think and talk of the North and to be intensely interested in it. * *

*

"Now

the Danish officials in Greenland are cautious folk. They are not

easily moved to praise or blame. And on matters concerning the north

and the pole they are scrupulously conservative. No emotion, no

sensation moves them. They do not see the pole through the mirage of

the south. When I noticed the signature to their telegrams I felt

that they meant much.

"Here

was a plain statement of a fact as stupendous as the first words

Columbus uttered, to express the truth that he had added a new world

to Leon and Castile. The news soon spread through Copenhagen, which

had heard great news of Peary and Nansen before. The town was stirred

as if Holger Dansker had risen from beneath the vaults of Kronborg

Castle — the castle of Elsinore — and walked into the streets.

Nobody questioned the truth of the story, for Knud Rasmussen's name

is a talisman, and the officers in Greenland do not take travelers'

tales seriously unless the travelers have serious claims.

"Later

came testimony from the great Norwegian explorer Amundsen and from

Captain Otto Sverdrup; and then the time of waiting. Even the boys in

the street were waiting for Cook. A new Danish joke began to

circulate. 'Do you believe that the cuckoo can prophesy?' 'Yes; once

in the spring, I asked who should be first at the North Pole and it

said, "Cook, Cook, Cook." '

CHILDREN

TOOK OFF CAPS.

"The

other day Dr. Cook drove with me through the streets of Copenhagen

and along the Strandvej to Charlottenlund, one of the summer palaces

of the King; even the little children waved their hands and took off

their caps. If he had been an explorer crowned with the laurels won

by the discovery of the South Pole, he would not have been so

interesting to these little people, but he came from a country which

they had heard about from the moment that they could hear at all —

a country which is very near to them. * * *

"Coming,

ardently expected, was a hero whom they could understand, and he

needed no explanation. That he was approved of by Knud Rasmussen,

half an Eskimo himself, who knows all the ways of the Eskimo, to whom

the snow and ice are as the forest bark and leaves are to our

Indians, was enough.

"To

me, knowing Dr. Cook through his articles in the Century and

Harper's, and through his entrancing 'First Antarctic Night,' it was

a great pleasure to think of his coming, and to believe that he had

added a new glory to Old Glory."

"How

Cook Came and Went" is the title of Dr. Egan's articles, and he

deals with details much more fully than have the cables. Coming down

to the morning of Dr. Cook's arrival in Copenhagen, he continues:

"When

I reached the environs of the harbor my coachmen would have found it

impossible to get near the open space reserved for members of the

Royal Geographical Society if it had not been for their red, white

and blue cockades, for which a passage was instantly made. The Crown

Prince was in position and tremendously interested. Near him was

Commodore Hovgaard, commander of the King's yacht, to whom the

success of the ceremonies attending the reception of Dr. Cook is

largely due.

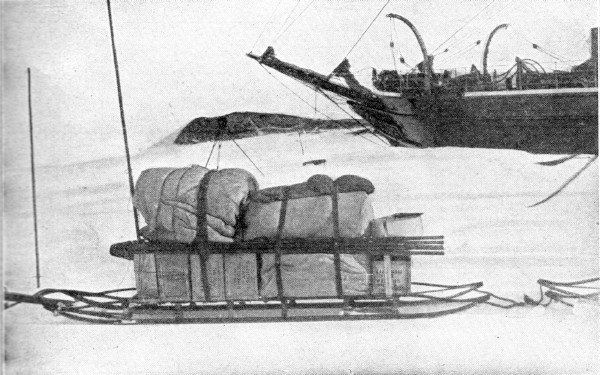

COOK'S SLED PACKED READY FOR THE DASH TO THE POLE.

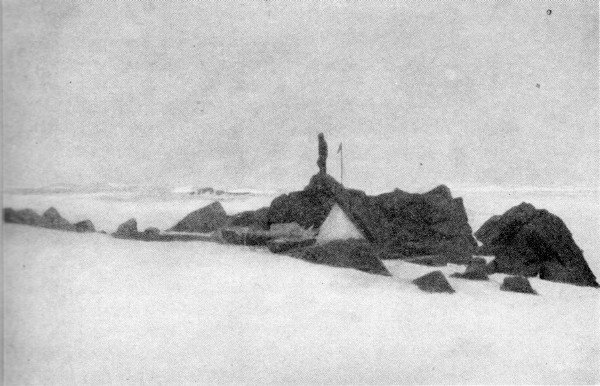

PEARY'S WINTER QUARTERS -- THE LOOKOUT

WATCHING THE RETURN OF THE SLEDGE PARTY.

TRAINING ESKIMO DOGS FOR THE PEARY EXPEDITION.

"It

was a beautiful morning; the Sound never looked bluer or seemed to be

more brilliantly flecked with silver spots. The crowd increased and I

began to know what pain a President had to suffer under the process

of congratulatory hand-shaking. The Crown Prince had an engagement to

preside at the laying of the cornerstone of a students' building at

ten o'clock. He is most punctual. When he goes to a ceremonious

convention himself he is always there at the exact time. When his

father, the King, goes he is invariably there five minutes before the

time. We still waited. The Crown Prince concluded that the students

would not be impatient, because they had the habit of taking 'the

academical quarter of an hour.' At last the Hans Egede appeared. The

expectancy of the great crowd grew intense and expressed itself in

silence.

"The

Crown Prince and the representatives of the Royal Geographical

Society and myself entered the launch. In a short time we were on the

deck of the Hans Egede.

PRINCE

GREETS HIM.

"Doctor

Cook, not by any means then the glittering butterfly of fashion into

which a tailor later in the morning transformed him, stood at the

head of the ladder. Prince Christian greeted him first; then I came.

He smiled: — 'You are the first American I have shaken hands with

for over two years,' he said. Afterward he explained, with that

careful regard for exact truth which is his characteristic, that he

had in the meantime shaken hands with Mr. Whitney, but that he looked

so much like an Eskimo that, for the moment, Doctor Cook had

forgotten his nationality.

"The

explorer in his rough and weather-beaten clothes, resembled somewhat

the familiar figure of Robinson Crusoe. Prince Valdemar, the Premier

Admiral of the Danish navy stood near him and most enthusiastically

congratulated the American people, through me, on this new glory to

the American flag. The thing after we landed was to know how to get

to our carriages.

"The

Crown Prince, through the cleverness of his Chamberlain, got safely

into his automobile, but Dr. Cook and Mr. W. T. Stead, whom I had

invited to share my carriage, were with myself pinned tight in the

enthusiastic, happy and energetic crowd. Dr. Cook had his sea legs

on, which in a crowd are not nearly so good as land legs; he had been

so used to the swaying deck that the solid soil was new to him. Mr.

Stead took him in his arms, held him tight and began to interview him

at once.

"It

took at least ten minutes to be propelled through a sea of applauding

and hand shaking people. I owe it entirely to the honesty of a

Copenhagen tailor that my coat tails were not torn off and that I was

lifted up the steps of the home of the Geographical Society with no

loss except one button. I am afraid that if the aegis of the United

States had not been upon me, which was both a halo and a nimbus on

this day, at least one of my ribs would have been broken. The

adventure recalled a Georgetown football game on Thanksgiving Day.

"Dr.

Cook was forced to make a little speech, and then, led by a private

way, he finally reached his hotel. There was to be no rest for him,

however. Knowing this, I arranged that he should come to the Legation

to lunch in quietness.

THE

DANISH FAREWELL.

"When

he left Copenhagen on the afternoon of the tenth, on his way to meet

the Scandinavian-American liner Oscar II," Dr. Egan writes, "he

was the center of admiring throngs. Among those last to say farewell

was Count Christian Holstein-Ledreborg, the son of the Prime

Minister, sent by his father to see him off.

"Flowers

were showered upon him. Old men and women asked to clasp his hand,

and at that moment he was the hero of this nation of Vikings. His

speeches on receiving the very high honor of the Royal Danish

Geographical Society's medal and on being made an honorary Doctor of

Philosophy in the University of Copenhagen were brief, direct and

simple. This university knows perfectly well how to blend in its

functions solemnity, simplicity and brevity. None of these functions

ever occurs without music forming part of it, and a great part, and

the cantata for an orchestra of stringed instruments which preceded

the short speeches was an admirable preparation for them.

"On

Friday, when he left, he was loaded with honors and followed by the

acclamations of the people. He stood for a few moments on the upper

deck of the Melchior. Admiral de Richelieu had toasted him, the

center of a crowd in the cabin; but now he stood alone, and the

cheers that greeted him were as much a tribute to his personal

character as to his epoch making exploit. Kindly, simple, firm and

sincere, he had in a short time made the sons of the Viking's love

him."

|