|

XV

HOW

THE

FIVE ANCIENTS BECAME MEN

BEFORE

the

earth was separated from the heavens, all there was was a great ball of

watery

vapor called chaos. And at that time the spirits of the five elemental

powers

took shape, and became the five Ancients. The first was called the

Yellow

Ancient, and he was the ruler of the earth. The second was called the

Red Lord,

and he was the ruler of the fire. The third was called the Dark Lord,

and he

was the ruler of the water. The fourth was known as the Wood Prince,

and he was

the ruler of the wood. The fifth was called the Mother of Metals, and

ruled

over them. These five Ancients set all their primal spirit into motion,

so that

water and earth sank down. The heavens floated upward, and the earth

grew firm

in the depths. Then they allowed the waters to gather into rivers and

seas, and

hills and plains made their appearance. So the heavens opened and the

earth was

divided. And there were sun, moon and all the stars, wind, clouds,

rain, and

dew. The Yellow Ancient set earth's purest power spinning in a circle,

and

added the effect of fire and water thereto. Then there came forth

grasses and

trees, birds and beasts, and the tribes of the serpents and insects,

fishes and

turtles. The Wood Prince and the Mother of Metals combined light and

darkness,

and thus created the human race as men and women. And thus the world

gradually

came to be.

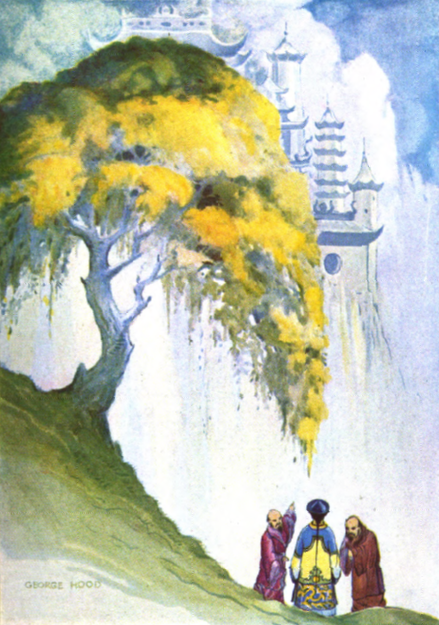

At that

time there was one who was known as the True Prince of the Jasper

Castle. He

had acquired the art of sorcery through the cultivation of magic. The

five

Ancients begged him to rule as the supreme god. He dwelt above the

three and

thirty heavens, and the Jasper Castle, of white jade with golden gates,

was

his. Before him stood the stewards of the eight-and-twenty houses of

the moon,

and the gods of the thunders and the Great Bear, and in addition a

class of

baneful gods whose influence was evil and deadly. They all aided the

True

Prince of the Jasper Castle to rule over the thousand tribes under the

heavens,

and to deal out life and death, fortune and misfortune. The Lord of the

Jasper

Castle is now known as the Great God, the White Jade Ruler.

The five

Ancients withdrew after they had done their work, and thereafter lived

in quiet

purity. The Red Lord dwells in the South as the god of fire. The Dark

Lord

dwells in the North, as the mighty master of the somber polar skies. He

lived

in a castle of liquid crystal. In later ages he sent Confucius down

upon earth

as a saint. Hence this saint is known as the Son of Crystal. The Wood

Prince

dwells in the East. He is honored as the Green Lord, and watches over

the

coming into being of all creatures. In him lives the power of spring

and he is

the god of love. The Mother of Metals dwells in the West, by the sea of

Jasper,

and is also known as the Queen-Mother of the West. She leads the rounds

of the

fairies, and watches over change and growth. The Yellow Ancient dwells

in the

middle. He is always going about in the world, in order to save and to

help

those in any distress. The first time he came to earth he was the

Yellow Lord,

who taught mankind all sorts of arts. In his later years he fathomed

the

meaning of the world on the Etherial Mount, and flew up to the radiant

sun.

Under the rule of the Dschou dynasty he was born again as Li Oerl, and

when he

was born his hair and beard were white, for 'which reason he was called

Laotsze, "Old Child." He wrote the book of "Meaning and

Life" and spread his teachings through the world. He is honored as the

head of Taoism. At the beginning of the reign of the Han dynasty, he

again

appeared as the Old Man of the River, (Ho Schang Gung). He spread the

teachings

of Tao abroad mightily, so that from that time on Taoism flourished

greatly.

These doctrines are known to this day as the teachings of the Yellow

Ancient.

There is also a saying: "First Laotsze was, then the heavens were."

And that must mean that Laotsze was that very same Yellow Ancient of

primal

days.

Note: "How

the

Five Ancients Became Men."

This fairy-tale, the first of the legends of the gods, is given in the

version

current among the people. In it the five elemental spirits of earth,

fire,

water, wood and metal are brought into connection with a creation myth.

"Prince of the Jasper Castle" or "The White Jade Ruler," Yu

Huang Di, is the popular Chinese synonym for "the good lord." The

phrase "White Jade" serves merely to express his dignity. All in all,

there are 32 other Yu Huangs, among whom he is the highest. He may be

compared

to Indra, who dwells in a heaven that also comprises 33 halls. The

astronomic

relationship between the two is very evident.

XVI

THE HERD

BOY AND THE WEAVING MAIDEN

THE

Herd

Boy was the child of poor people. When he was twelve years old, he took

service

with a farmer to herd his cow. After a few years the cow had grown

large and

fat, and her hair shone like yellow gold. She must have been a cow of

the gods.

One day

while he had her out at pasture in the mountains, she suddenly began to

speak

to the Herd Boy in a human voice, as follows: "This is the Seventh Day.

Now the White Jade Ruler has nine daughters, who bathe this day in the

Sea of

Heaven. The seventh daughter is beautiful and wise beyond all measure.

She

spins the cloud-silk for the King and Queen of Heaven, and presides

over the

weaving which maidens do on earth. It is for this reason she is called

the

Weaving Maiden. And if you go and take away her clothes while she

bathes, you

may become her husband and gain immortality."

"But

she is up in Heaven," said the Herd Boy, "and how can I get

there?"

"I

will carry you there," answered the yellow cow.

So the

Herd Boy climbed on the cow's back. In a moment clouds began to stream

out of

her hoofs, and she rose into the air. About his ears there was a

whistling like

the sound of the wind, and they flew along as swiftly as lightning.

Suddenly

the cow stopped.

"Now

we are here," said she.

Then round

about him the Herd Boy saw forests of chrysophrase and trees of jade.

The grass

was of jasper and the flowers of coral. In the midst of all this

splendor lay a

great, four-square sea, covering some five-hundred acres. Its green

waves rose

and fell, and fishes with golden scales were swimming about in it. In

addition

there were countless magic birds who winged above it and sang. Even in

the distance

the Herd Boy could see the nine maidens in the water. They had all laid

down

their clothes on the shore.

"Take

the red clothes, quickly," said the cow, "and hide away with them in

the forest, and though she ask you for them never so sweetly do not

give them

back to her until she has promised to become your wife."

Then the

Herd Boy hastily got down from the cow's back, seized the red clothes

and ran

away. At the same moment the nine maidens noticed him and were much

frightened.

"O

youth, whence do you come, that you dare to take our clothes?" they

cried.

"Put them down again quickly!”

But the

Herd Boy did not let what they said trouble him; but crouched down

behind one

of the jade trees. Then eight of the maidens hastily came ashore and

drew on

their clothes.

"Our

seventh sister," said they, "whom Heaven has destined to be yours,

has come to you. We will leave her alone with you."

The

Weaving Maiden was still crouching in the water.

But the

Herd Boy stood before her and laughed. "If you will promise to be my

wife," said he, "then I will give you your clothes."

But this

did not suit the Weaving Maiden.

"I am

a daughter of the Ruler of the Gods," said she, "and may not marry

without his command. Give back my clothes to me quickly, or else my

father will

punish you!"

Then the

yellow cow said: "You have been destined for each other by fate, and I

will be glad to arrange your marriage, and your father, the Ruler of

the Gods,

will make no objection. Of that I am sure."

The

Weaving Maiden replied: "You are an unreasoning animal! How could you

arrange our marriage?"

The cow

said: "Do you see that old willow-tree there on the shore? Just give it

a

trial and ask it? If the willow tree speaks, then Heaven wishes your

union."

And the

Weaving Maiden asked the willow.

The willow

replied in a human voice:

"This

is the Seventh day,

The

Herd

Boy his court to the Weaver doth pay!"

and the Weaving

Maiden was

satisfied with the verdict. The Herd Boy laid down her clothes, and

went on

ahead. The Weaving Maiden drew them on and followed him. And thus they

became

man and wife.

But after

seven days she took leave of him.

"The

Ruler of Heaven has ordered me to look after my weaving," said she.

"If I delay too long I fear that he will punish me. Yet, although we

have

to part now, we will meet again in spite of it."

When she

had said these words she really went away. The Herd Boy ran after her.

But when

he was quite near she took one of the long needles from her hair and

drew a

line with it right across the sky, and this line turned into the Silver

River.

And thus they now stand, separated by the River, and watch for one

another.

And since

that time they meet once every year, on the eve of the Seventh Day.

When that

time comes, then all the crows in the world of men come flying and form

a

bridge over which the Weaving Maiden crosses the Silver River. And on

that day

you will not see a single crow in the trees, from morning to night, no

doubt

because of the reason I have mentioned. And besides, a fine rain often

falls on

the evening of the Seventh Day. Then the women and old grandmothers say

to one

another: "Those are the tears which the Herd Boy and the Weaving Maiden

shed at parting!" And for this reason the Seventh Day is a rain

festival.

To the

west of the Silver River is the constellation of the Weaving Maiden,

consisting

of three stars. And directly in front of it are three other stars in

the form

of a triangle. It is said that once the Herd Boy was angry because the

Weaving

Maiden had not wished to cross the Silver River, and had thrown his

yoke at

her, which fell down just in front of her feet. East of the Silver

River is the

Herd Boy's constellation, consisting of six stars. To one side of it

are

countless little stars which form a constellation pointed at both ends

and

somewhat broader in the middle. It is said that the Weaving Maiden in

turn

threw her spindle at the Herd Boy; but that she did not hit him, the

spindle

falling down to one side of him.

Note: "The

Herd

Boy and the Weaving Maiden"

is retold after an oral source. The Herd Boy is a constellation in

Aquila, the

Weaving Maiden one in Lyra. The Silver River which separates them is

the Milky

Way. The Seventh Day of the seventh month is the festival of their

reunion. The

Ruler of the Heavens has nine daughters in all, who dwell in the nine

heavens.

The oldest married Li Mang (comp. Notschka, No. 18); the second is the

mother

of Yang Oerlang (comp. No. 17); the third is the mother of the planet

Jupiter

(comp. "Sky O'

Dawn," No. 37); and the fourth dwelt with a pious and industrious

scholar,

by name of Dung Yung, whom she aided to win riches and honor. The

seventh is

the Spinner, and the ninth had to dwell on earth as a slave because of

some

transgression of which she had been guilty. Of the fifth, the sixth and

the

eighth daughters nothing further is known.

XVII

YANG OERLANG

THE

second

daughter of the Ruler of Heaven once came down upon the earth and

secretly

became the wife of a mortal man named Yang. And when she returned to

Heaven she

was blessed with a son. But the Ruler of Heaven was very angry at this

desecration of the heavenly halls. He banished her to earth and covered

her

with the Wu-I hills. Her son, however, Oerlang by name, the nephew of

the Ruler

of Heaven, was extraordinarily gifted by nature. By the time he was

full grown

he had learned the magic art of being able to control eight times nine

transformations. He could make himself invisible, or could assume the

shape of

birds and beasts, grasses, flowers, snakes and fishes, as he chose. He

also

knew how to empty out seas and remove mountains from one place to

another. So

he went to the Wu-I hills and rescued his mother, whom he took on his

back and

carried away. They stopped to rest on a flat ledge of rock.

Then the

mother said: "I am very thirsty!"

Oerlang

climbed down into the valley in order to fetch her water, and some time

passed

before he returned. When he did his mother was no longer there. He

searched

eagerly, but on the rock lay only her skin and bones, and a few

blood-stains.

Now you must know that at that time there were still ten suns in the

heavens,

glowing and burning like fire. The Daughter of Heaven, it is true, was

divine

by nature; yet because she had incurred the anger of her father and had

been

banished to earth, her magic powers had failed her. Then, too, she had

been

imprisoned so long beneath the hills in the dark that, coming out

suddenly into

the sunlight, she had been devoured by its blinding radiance.

When

Oerlang thought of his mother's sad end, his heart ached. He took two

mountains

on his shoulders, pursued the suns and crushed them to death between

the

mountains. And whenever he had crushed another sun-disk, he picked up a

fresh

mountain. In this way he had already slain nine of the ten suns, and

there was

but one left. And as Oerlang pursued him relentlessly, he hid himself

in his

distress beneath the leaves of the portulacca plant. But there was a

rainworm

close by who betrayed his hiding-place, and kept repeating: "There he

is!

There he is!"

Oerlang

was about to seize him, when a messenger from the Ruler of the Heaven

suddenly

descended from the skies with a command: "Sky, air and earth need the

sunshine. You must allow this one sun to live, so that all created

beings may

live. Yet, because you rescued your mother, and showed yourself to be a

good

son, you shall be a god, and be my bodyguard in the Highest Heaven, and

shall

rule over good and evil in the mortal world, and have power over devils

and

demons." When Oerlang received this command he ascended to Heaven.

Then the

sun-disk came out again from beneath the portulacca leaves, and out of

gratitude, since the plant had saved him, he bestowed upon it the gift

of a

free-blooming nature, and ordained that it never need fear the

sunshine. To

this very day one may see on the lower side of the portulacca leaves

quite

delicate little white pearls. They are the sunshine that remained

hanging to

the leaves when the sun hid under them. But the sun pursues the

rainworm, when

he ventures forth out of the ground, and dries him up as a punishment

for his

treachery.

Since that

time Yang Oerlang has been honored as a god. He has oblique, sharply

marked

eyebrows, and holds a double-bladed, three-pointed sword in his hand.

Two

servants stand beside him, with a falcon and a hound; for Yang Oerlang

is a

great hunter. The falcon is the falcon of the gods, and the hound is

the hound

of the gods. When brute creatures gain possession of magic powers or

demons

oppress men, he subdues them by means of the falcon and hound.

Note: Yang

Oerlang is a huntsman, as is indicated by

his falcon and hound. His Hound of the Heavens, literally "the divine,

biting hound" recalls the hound of Indra. The myth that there were

originally ten suns in the skies, of whom nine were shot down by an

archer, is

also placed in the period of the ruler Yau. In that story the archer is

named

Hou-I, or I (comp. No. 19). Here, instead of the shooting down of the

suns with

arrows, we have the Titan motive of destruction with the mountains.

XVIII

NOTSCHA

THE

oldest

Daughter of the Ruler of Heaven had married the great general Li Dsing.

her

sons vere named Gintscha, Mutscha and Notscha, But when Notscha was

given her,

she dreamed at night that a Taoist priest came into her chamber and

said:

"Swiftly receive the Heavenly Son!" And straightway a radiant pearl

glowed within her. And she was so frightened at her dream that she

awoke. And

when Notscha came into the world, it seemed as though a ball of flesh

were

turning in circles like a wheel, and the whole room was filled with

strange

fragrances and a crimson light.

Li Dsing

was much frightened, and thought it was an apparition. He clove the

circling

ball with his sword, and out of it leaped a small boy whose whole body

glowed

with a crimson radiance. But his face was delicately shaped and white

as snow.

About his right arm he wore a golden armlet and around his thighs was

wound a

length of crimson silk, whose glittering shine dazzled the eyes. When

Li Dsing

saw the child he took pity on him and did not slay him, while his wife

began to

love the boy dearly.

When three

days had passed, all his friends came to wish him joy. They were just

sitting

at the festival meal when a Taoist priest entered and said: "I am the

Great One. This boy is the bright Pearl of the Beginning of Things,

bestowed

upon you as your son. Yet the boy is wild and unruly, and will kill

many men.

Therefore I will take him as my pupil to gentle his savage ways." Li

Dsing

bowed his thanks and the Great One disappeared.

When

Notscha was seven years old he once ran away from home. He came to the

river of

nine bends, whose green waters flowed along between two rows of

weeping-willows. The day was hot, and Notscha entered the water to cool

himself. He unbound his crimson silk cloth and whisked it about in the

water to

wash it. But while Notscha sat there and whisked about his scarf in the

water,

it shook the castle of the Dragon-King of the Eastern Sea to its very

foundations. So the Dragon-King sent out a Triton, terrible to look

upon, who

was to find out what was the matter. When the Triton saw the boy he

began to

scold. But the latter merely looked up and said: "What a

strange-looking

beast you are, and you can actually talk!" Then the Triton grew

enraged,

leaped up and struck at Notscha with his ax. But the latter avoided the

blow,

and threw his golden armlet at him. The armlet struck the Triton on the

head

and he sank down dead.

Notscha

laughed and said: "And there he has gone and made my armlet bloody!"

And he once more sat down on a stone, in order to wash his armlet. Then

the

crystal castle of the dragon began to tremble as though it were about

to fall

apart. And a watchman also came and reported that the Triton had been

slain by

a boy. So the Dragon-King sent out his son to capture the boy. And the

son seated

himself on the water-cleaving beast, and came up with a thunder of

great waves

of water. Notscha straightened up and said: "That is a big wave!"

Suddenly he saw a creature rise out of the waves, on whose back sat an

armed

man who cried in a loud voice: "Who has slain my Triton?" Notscha

answered: "The Triton wanted to slay me so I killed him. What

difference

does it make?" Then the dragon assailed him with his halberd. But

Notscha

said: "Tell me who you are before we fight." "I am the son of

the Dragon-King," was the reply. "And I am Notscha, the son of

General Li Dsing. You must not rouse my anger with your violence, or I

will

skin you, together with that old mud-fish, your father!" Then the

dragon

grew wild with rage, and came storming along furiously. But Notscha

cast his

crimson cloth into the air, so that it flashed like a ball of fire, and

cast

the dragon-youth from his breast. Then Notscha took his golden armlet

and

struck him on the forehead with it, so that he had to reveal himself in

his true

form as a golden dragon, and fall down dead.

Notscha

laughed and said: "I have heard tell that dragon-sinews make good

cords. I

will draw one out and bring it to my father, and he can tie his armor

together

with it." And with that he drew out the dragon's back sinew and took it

home.

In the

meantime the Dragon-King, full of fury, had hastened to Notscha's

father Li

Dsing and demanded that Notscha be delivered up to him. But Li Dsing

replied:

"You must be mistaken, for my boy is only seven years old and incapable

of

committing such misdeeds." While they were still quarreling Notscha

came

running up and cried: "Father, I'm bringing along a dragon's sinew for

you, so that you may bind up your armor with it!" Now the dragon broke

out

into tears and furious scolding. He threatened to report Li Dsing to

the Ruler

of the Heaven, and took himself off, snorting with rage.

Li Dsing

grew very much excited, told his wife what had happened, and both began

to

weep. Notscha, however, came to them and said: "Why do you weep? I will just go

to my master, the Great One, and he will

know what is to be done." And no sooner had he said the words than he

had

disappeared. He came into his master's presence and told him the whole

tale.

The latter said: "You must get ahead of the dragon, and prevent him

from

accusing you in Heaven!" Then he did some magic, and Notscha found

himself

set down by the gate of Heaven, where he waited for the dragon. It was

still

early in the morning; the gate of Heaven had not yet been opened, nor

was the

watchman at his post. But the dragon was already climbing up. Notscha,

whom his

master's magic had rendered invisible, threw the dragon to the ground

with his

armlet, and began to pitch into him. The dragon scolded and screamed.

"There the old worm flounders about," said Notscha, "and does

not care how hard he is beaten! I will scratch off some of his scales."

And with these words he began to tear open the dragon's festal

garments, and

rip off some of the scales beneath his left arm, so that the red blood

dripped

out. Then the dragon could no longer stand the pain and begged for

mercy. But

first he had to promise Notscha, that he would not complain of him,

before the

latter would let him go. And then the dragon had to turn himself into a

little

green snake, which Notscha put into his sleeve and took back home with

him. But

no sooner had he drawn the little snake from his sleeve than it assumed

human

shape. The dragon then swore that he would punish Li Dsing in a

terrible

manner, and disappeared in a flash of lightning.

Li Dsing

was now angry with his son in earnest. Therefore Notscha's mother sent

him to

the rear of the house to keep out of his father's sight. Notscha

disappeared

and went to his master, in order to ask him what he should do when the

dragon

returned. His master advised him and Notscha went back home. And all

the Dragon

Kings of the four seas were assembled, and had bound his parents, with

cries

and tumult, in order to punish them. Notscha ran up and cried with a

loud

voice: "I will take the punishment for whatever I have done! My parents

are blameless! What is the punishment you wish to lay upon me?" "Life

for life!" said the dragon. "Very well then, I will destroy

myself!" And so he did and the dragons went off satisfied; while

Notscha's

mother buried him with many tears.

But the

spiritual part of Notscha, his soul, fluttered about in the air, and

was driven

by the wind to the cave of the Great One. He took it in and said to it:

"You must appear

to your mother! Forty

miles distant from your home rises a green mountain cliff. On this

cliff she

must build a shrine for you. And after you have enjoyed the incense of

layman

adoration for three years, you shall once more have a human body."

Notscha

appeared to his mother in a dream, and gave her the whole message, and

she

awoke in tears. But Li Dsing grew angry when she told him about it. "It

serves the accursed boy right that he is dead! It is because you are

always

thinking of him that he appears to you in dreams. You must pay no

attention to

him." The woman said no more, but thenceforward he appeared to her

daily,

as soon as she closed her eyes, and grew more and more urgent in his

demand.

Finally all that was left for her to do was to erect a temple for

Notscha

without Li Dsing's knowledge.

And Notscha

performed great miracles in his temple. All prayers made in it were

granted.

And from far away people streamed to it to burn incense in his honor.

Thus half

a year passed. Then Li Dsing, on the occasion of a great military

drill, once

came by the cliff in question, and saw the people crowding thickly

about the

hill like a swarm of ants. Li Dsing inquired what there were to see

upon the

hill. "It is a new god, who performs so many miracles that people come

from far and near to honor him." "What sort of a god is he?"

asked Li Dsing. They did not dare conceal from him who the god was.

Then Li

Dsing grew angry. He spurred his horse up the hill and, sure enough,

over the

door of the temple was written: "Notscha's Shrine." And within it was

the likeness of Notscha, just as he had appeared while living. Li Dsing

said:

"While you were alive you brought misfortune to your parents. Now that

you

are dead you deceive the people. It is disgusting!" With these words he

drew forth his whip, beat Notscha's idolatrous likeness to pieces with

it, had

the temple burned down, and the worshipers mildly reproved. Then he

returned

home.

Now

Notscha had been absent in the spirit upon that day. When he returned

he found

his temple destroyed; and the spirit of the hill gave him the details.

Notscha

hurried to his master and related with tears what had befallen him. The

latter

was roused and said: "It is Li Dsing's fault. After you had given back

your body to your parents, you were no further concern of his. Why

should he

withdraw from you the enjoyment of the incense?" Then the Great One

made a

body of lotus-plants, gave it the gift of life, and enclosed the soul

of

Notscha within it. This done he called out in a loud voice: "Arise!"

A drawing of breath was heard, and Notscha leaped up once more in the

shape of

a small boy. He flung himself down before his master and thanked him.

The

latter bestowed upon him the magic of the fiery lance, and Notscha

thenceforward had two whirling wheels beneath his feet: The wheel of

the wind and

the wheel of fire.

With these he could

rise up and down in the air. The master also gave him a bag of

panther-skin in

which to keep his armlet and his silken cloth.

Now

Notscha had determined to punish Li Dsing. Taking advantage of a moment

when he

was not watched, he went away, thundering along on his rolling wheels

to Li

Dsing's dwelling. The latter was unable to withstand him and fled. He

was

almost exhausted when his second son, Mutscha, the disciple of the holy

Pu

Hain, came to his aid from the Cave of the White Crane. A violent

quarrel took

place between the brothers; they began to fight, and Mutscha was

overcome;

while Notscha once more rushed in pursuit of Li Dsing. At the height of

his

extremity, however, the holy Wen Dschu of the Hill of the Five Dragons,

the

master of Gintscha, Li Dsing's oldest son, stepped forth and hid Li

Dsing in

his cave. Notscha, in a rage, insisted that he be delivered up to him;

but Wen

Dschu said: "Elsewhere you may indulge your wild nature to your heart's

content, but not in this place."

And when

Notscha in the excess of his rage turned his fiery lance upon him, Wen

Dschu

stepped back a pace, shook the seven-petaled lotus from his sleeve, and

threw

it into the air. A whirlwind arose, clouds and mists obscured the

sight, and

sand and earth were flung up from the ground. Then the whirlwind

collapsed with

a great crash. Notscha fainted, and when he regained consciousness

found

himself bound to a golden column with three thongs of gold, so that he

could no

longer move. Wen Dschu now called Gintseha to him and ordered him to

give his

unruly brother a good thrashing. And this he did, while Notscha,

obliged to

stand it, stood grinding his teeth. In his extremity he saw the Great

One

floating by, and called out to him: "Save me, O Master!" But the

latter did not notice him; instead he entered the cave and thanked Wen

Dschu

for the severe lesson which he had given Notscha. Finally they called

Notscha

in to them and ordered him to be reconciled to his father. Then they

dismissed

them both and seated themselves to play chess. But no sooner was

Notscha free

than he again fell into a rage, and renewed his pursuit of his father.

He had

again overtaken Li Dsing when still another saint came forward to

defend the

latter. This time it was the old Buddha of the Radiance of the Light.

When

Notscha attempted to battle with him he raised his arm, and a pagoda

shaped

itself out of red, whirling clouds and closed around Notscha. Then

Radiance of

Light placed both his hands on the pagoda and a fire arose within it

which

burned Notscha so that he cried loudly for mercy. Then he had to

promise to beg

his father's forgivenness and always to obey him in the future. Not

till he had

promised all this did the Buddha let him out of the pagoda again. And

he gave

the pagoda to Li Dsing; and taught him a magic saying which would give

him the

mastery over Notscha. It is for this reason that Li Dsing is called the

Pagoda-bearing King of Heaven.

Later on

Li Dsing and his three sons, Gintcha, Mutscha and Notscha, aided King

Wu of fhe

Dschou dynasty to destroy the tyrant Dschou-Sin.

None could

withstand their might. Only once did a sorcerer succeed in wounding

Notscha in

the left arm. Any other would have died of the wound. But the Great One

carried

him into his cave, healed his wound and gave him three goblets of the

wine of

the gods to drink, and three fire-dates to eat. When Notscha had eaten

and

drunk he suddenly heard a crash at his left side and another arm grew

out from

it. He could not speak and his eyes stood out from their sockets with

horror.

But it went on as it had began: six more arms grew out of his body and

two more

heads, so that finally he had three heads and eight arms. He called out

to his

Master: "What does all this mean?" But the latter only laughed and

said: "All is as it should be. Thus epuipped you will really be

strong!" Then he taught him a magic incantation by means of which he

could

make his arms and heads visible or invisible as he chose. When the

tyrant

Dschou-Sin had been destroyed, Li Dsing and his three sons, while still

on

earth, were taken up into heaven and seated among the gods.

Note: Li

Dsing,

the Pagoda-bearing King of Heaven,

may be traced back to Indra, the Hindoo god of thunder and lightning.

The

Pagoda might be an erroneous variant of the thunderbolt Vadjra. In such

case

Notscha would be a personification of the thunder. The Great One (Tai

I), is

the condition of things before their separation into the active and

passive

principles. There is a whole geneology of mythical saints and holy men

who took

part in the battles between King Mu of Dschou and the tyrant

Dschou-Sin. These

saints are, for the

most part, Buddhist-Brahminic figures which have been reshaped. The

Dragon-King

of the Eastern Sea also occurs in the tale of Sun Wu Kung (No. 73).

"Dragon sinew" means the spinal cord, the distinction between nerves

and sinews not being carefully observed. "Three spirits and seven

souls": man has three spirits, usually

above his head, and seven animal souls. "Notscha had been absent in the

spirit upon that day": the idol is only the seat of the godhead, which

the

latter leaves or inhabits as he chooses. Therefore the godhead must be

summoned

when prayers are offered, by means of bells and incense. When the god

is not

present, his idol is merely a block of wood or stone. Pu Hain, the

Buddha of

the Lion, is the Indian Samantabharda, one of the four great

Buddhisatvas of

the Tantra School. Wen Dschu, the Buddha on the Golden-haired Mountain

Lion,

(Hon), is the Indian Mandjusri. The old Buddha of the Radiance of the

Light,

Jan Dong Go Fu, is the Indian Dipamkara.

XIX

THE LADY

OF THE MOON

IN

the

days of the Emperor Yau lived a prince by the name of Hou I, who was a

mighty

hero and a good archer. Once ten suns rose together in the sky, and

shone so

brightly and burned so fiercely that the people on earth could not

endure them.

So the Emperor ordered Hon I to shoot at them. And Hon I shot nine of

them down

from the sky. Beside his bow, Hou I also had a horse which ran so

swiftly that

even the wind could not catch up with it. He mounted it to go

a-hunting, and

the horse ran away and could not be stopped. So Hou I came to Kunlun

Mountain

and met the Queen-Mother of the Jasper Sea. And she gave him the herb

of

immortality. He took it home with him and hid it in his room. But his

wife who

was named Tschang O, once ate some

of it on the sly

when he was not at home, and she immediately floated up to the clouds.

When she

reached the moon, she ran into the castle there, and has lived there

ever since

as the Lady of the Moon.

On a night

in mid-autumn, an emperor of the Tang dynasty once sat at wine with two

sorcerers. And one of them took his bamboo staff and cast it into the

air,

where it turned into a heavenly bridge, on which the three climbed up

to the

moon together. There they saw a great castle on which was inscribed:

"The

Spreading Halls of Crystal Cold." Beside it stood a cassia tree which

blossomed and gave forth a fragrance filling all the air. And in the

tree sat a

man who was chopping off the smaller boughs with an ax. One of the

sorcerers

said: "That is the man in the moon. The cassia tree grows so

luxuriantly

that in the course of time it would overshadow all the moon's radiance.

Therefore it has to be cut down once in every thousand years." Then

they

entered the spreading halls. The silver stories of the castle towered

one above

the other, and its walls and columns were all formed of liquid crystal.

In the

walls were cages and ponds, where fishes and birds moved as though

alive. The whole

moon-world seemed made of glass. While they were still looking about

them on

all sides the Lady of the Moon stepped up to them, clad in a white

mantle and a

rainbow-colored gown. She smiled and said to the emperor: "You are a

prince of the mundane world of dust. Great is your fortune, since you

have been

able to find your way here!" And she called for her attendants, who

came

flying up on white birds, and sang and danced beneath the cassia tree.

A pure

clear music floated through the air. Beside the tree stood a mortar

made of

white marble, in which a jasper rabbit ground up herbs. That was the

dark half

of the moon. When the dance had ended, the emperor returned to earth

again with

the sorcerers. And he had the songs which he had heard on the moon

written down

and sung to the accompaniment of flutes of jasper in his pear-tree

garden.

"BESIDE

IT

STOOD

A CASSIA-TREE."

Note: This

fairy-tale is traditional. The archer Hon

I (or Count I, the Archer-Prince, comp. Dschuang Dsi), is placed by

legend in

different epochs. He also occurs in connection with the myths regarding

the

moon, for one tale recounts how he saved the moon during an eclipse by

means of

his arrows. The Queen-Mother is Si Wang Mu (comp. with No. 15). The

Tang

dynasty reigned 618-906 A. D.

"The Spreading Halls of Crystal Cold": The goddess of the ice also

has her habitation in the moon. The hare in the moon is a favorite

figure. He

grinds the grains of maturity or the herbs that make the elixir of

life. The

rain-toad Tschan, who has three legs, is also placed on the moon.

According to

one version of the story, Tschang O took the

shape of this toad.

XX

THE

MORNING AND THE EVENING STAR

ONCE

upon

a time there were two stars, sons of the Golden King of the Heavens.

The one

was named Tschen and the other Shen. One day they quarreled, and Tschen

struck

Shen a terrible blow. Thereupon both stars made a vow that they would

never

again look upon each other. So Tschen only appears in the evening, and

Shen

only appears in the morning, and not until Tschen has disappeared is

Shen again

to be seen. And that is why people say: "When two brothers do not live

peaceably with one another they are like Tschen and Shen."

Note:

Tschen and Shen are Hesperus and Lucifer, the morning and evening

stars. The

tale is told in its traditional form.

XXI

THE GIRL

WITH THE HORSE'S HEAD

OR

THE

SILKWORM GODDESS

IN

the dim

ages of the past there once was an old man

who went on a journey. No one remained at home

save his only

daughter and a white stallion. The daughter fed the horse day by day,

but she

was lonely and yearned for her father.

So it

happened that one day she said in jest to the horse: "If you will bring

back my father to me then I will marry you!"

No sooner

had the horse heard her say this, than he broke loose and ran away. He

ran

until he came to the place where her father was. When her father saw

the horse,

he was pleasantly surprised, caught him and seated himself on his back.

And the

horse turned back the way he had come, neighing without a pause.

"What

can be the matter with the horse?" thought the father. "Something

must have surely gone wrong at home!" So he dropped the reins and rode

back. And he fed the horse liberally because he had been so

intelligent; but

the horse ate nothing, and when he saw the girl, he struck out at her

with his

hoofs and tried to bite her. This surprised the father; he questioned

his

daughter, and she told him the truth, just as it had occurred.

"You

must not say a word about it to any one," spoke her father, "or else

people will talk about us."

And he

took down his

crossbow, shot the horse,

and hung up his skin in the yard to dry. Then he went on his travels

again.

One day

his daughter went out walking with the daughter of a neighbor. When

they

entered the yard, she pushed the horse-hide with her foot and said:

"What

an unreasonable animal you were — wanting to marry a human being! What happened

to you served you right!"

But before

she had finished her speech, the horsehide moved, rose up, wrapped

itself about

the girl and ran off.

Horrified,

her companion ran home to her father and told him what had happened.

The

neighbors looked for the girl everywhere, but she could not be found.

At last,

some days afterward, they saw the girl hanging from the branches of a

tree,

still wrapped in the horse-hide; and gradually she turned into a

silkworm and

wove a cocoon. And the threads which she spun were strong and thick.

Her girl

friend then took down the cocoon and let her slip out of it; and then

she spun

the silk and sold it at a large profit.

But the

girl's relatives longed for her greatly. So one day the girl appeared

riding in

the clouds on her horse, followed by a great company and said: "In

heaven

I have been assigned to the task of watching over the growing of

silkworms. You

must yearn for me no longer!" And thereupon they built temples to her

in

her native land, and every year, at the silkworm season, sacrifices are

offered

to her and her protection is implored. And the Silkworm Goddess is also

known

as the girl with the Horse's Head.

Note: This

tale

is placed in the times of the Emperor

Hau, and the legend seems to have originated in Setchuan. The stallion

is the

sign of the zodiac which rules the springtime, the season when the

silkworms

are cultivated. Hence she is called the Goddess with the Horse's Head.

The

legend itself tells a different tale. In addition to this goddess, the

spouse

of Schen Nung, the "Divine Husbandman," is also worshiped as the

goddess of silkworm culture. The Goddess with the Horse's Head is more

of a totemic

representation of the silkworm as such; while the wife of Schen Nung is

regarded as the protecting goddess of silk culture,

and is supposed to have been the first to teach women its details. The

spouse

of the Yellow Lord is mentioned in the same connection. The popular

belief

distinguishes three goddesses who protect the silkworm culture in turn.

The

second is the best of the three, and when it is her year the silk turns

out

well.

XXII

THE QUEEN

OF HEAVEN

THE

Queen

of Heaven, who is also known as the Holy Mother, was in mortal life a

maiden of

Fukien, named Lin. She was pure, reverential and pious in her ways and

died at

the age of seventeen. She shows her power on the seas and for this

reason the

seamen worship her. When they are unexpectedly attacked by wind and

waves, they

call on her and she is always ready to hear their pleas.

There are

many seamen in Fukien, and every year people are lost at sea. And

because of

this, most likely, the Queen of Heaven took pity on the distress of her

people

during her lifetime on earth. And since her thoughts are

uninterruptedly turned

toward aiding the drowning in their distress, she now appears

frequently on the

seas.

In every

ship that sails a picture of the Queen of Heaven hangs in the cabin,

and three

paper talismans are also kept on shipboard. On the first she is painted

with

crown and scepter, on the second as a maiden in ordinary dress, and on

the

third she is pictured with flowing hair, barefoot, standing with a

sword in her

hand. When the ship is in danger the first talisman is burnt, and help

comes.

But if this is of no avail, then the second and finally the third

picture is

burned. And if no help comes then there is nothing more to be done.

When

seamen lose their course among wind and waves and darkling clouds, they

pray

devoutly to the Queen of Heaven. Then a red lantern appears on the face

of the

waters. And if they follow the lantern they will win safe out of all

danger.

The Queen of Heaven may often be seen standing in the skies, dividing

the wind

with her sword. When she does this the wind departs for the North and

South,

and the waves grow smooth.

A wooden

wand is always kept before her holy picture in the cabin. It often

happens that

the fish-dragons play in the seas. They are two giant fish who spout up

water

against one another till the sun in the sky is obscured, and the seas

are

shrouded in profound darkness. And often, in the distance, one may see

a bright

opening in the darkness. If the ship holds a course straight for this

opening

it will win through, and is suddenly floating in calm

waters again. Looking back, one may see the two fishes still spouting

water,

and the ship will have passed directly beneath their jaws. But a storm

is

always near when the fish dragons swim; therefore it is well to burn

paper or

wool so that the dragons do not draw the ship down into the depths. Or

the

Master of the Wand may burn incense before the wand in the cabin. Then

he must

take the wand and swing it over the water three times, in a circle. If

he does

so the dragons will draw in their tails and disappear.

When the

ashes in the censer fly up into the air without any cause, and are

scattered

about, it is a sign that great danger is threatening.

Nearly

two-hundred years ago an army was fitted out to subdue the island of

Formosa.

The captain's banner had been dedicated with the blood of a white

horse.

Suddenly the Queen of Heaven appeared at the tip of the banner-staff.

In

another moment she had disappeared, but the invasion was successful.

On another

occasion, in the days of Kien Lung, the minister Dschou Ling was

ordered to

install a new king in the Liu-Kin Islands. When the fleet was sailing

by south

of Korea, a storm arose, and his ship was driven toward the Black

Whirlpool.

The water had the color of ink, sun and moon lost their radiance, and

the word

was passed about that the ship had been caught in the Black Whirlpool,

from

which no living man had ever returned. The seaman and travelers awaited

their

end with lamentations. Suddenly an untold number of lights, like red

lanterns,

appeared on the surface of the water. Then the seamen were overjoyed

and prayed

in the cabins. "Our lives are saved!" they cried, "the Holy

Mother has come to our aid!"

And truly, a beautiful maiden with golden earrings appeared. She waved

her hand

in the air and the winds became still and the waves grew even. And it

seemed as

though the ship were being drawn along by a mighty hand. It moved

plashing

through the waves, and suddenly it was beyond the limits of the Black

Whirlpool.

Dschou

Ling on his return told of this happening, and begged that temples be

erected

in honor of the Queen of Heaven, and that she be included in the list

of the

gods. And the emperor, granted his prayer.

Since then

temples of the Queen of Heaven are to be found in all sea-port towns,

and her

birthday is celebrated on the eighth day of the fourth month with

spectacles

and sacrifices.

Note: "The

Queen of Heaven," whose name is

Tian Hau, or more exactly, Tian Fe Niang Niang, is a Taoist goddess of

seamen,

generally worshiped in all coast towns. Her story is principally made

up of

local legends of Fukian province, and a variation of the Indian

Maritschi (who

as Dschunti with the eight arms, is the object of quite a special

cult). Tian

Hou, since the establishment of the Manchu dynasty, is one of the

officially

recognized godheads.

XXIII

THE

FIRE-GOD

LONG

before the time of Fu Hi, Dschu Yung, the Magic Welder, was the ruler

of men.

He discovered the use of fire, and succeeding generations learned from

him to

cook their food. Hence his descendents were intrusted with the

preservation of

fire, while he himself was made the Fire-God. He is a personification

of the

Red Lord, who showed himself at the beginning of the World as one of

the Five

Ancients. The Fire-God is worshiped as the Lord of the Holy Southern

Mountain.

In the skies the Fiery Star, the southern quarter of the heavens and

the Red

Bird belong to his domain. When there is danger of fire the Fiery Star

glows

with a peculiar radiance. When countless numbers of fire-crows fly into

a

house, a fire is sure to break out in it.

In the

land of the four rivers there dwelt a man who was very rich. One day he

got

into his wagon and set out on a long journey. And he met a girl,

dressed in

red, who begged him to take her with him. He allowed her to get into

the wagon,

and drove along for half-a-day

without even looking in her direction. Then the girl got out again and

said in

farewell: "You are truly a good and honest man, and for that reason I

must

tell you the truth. I am the Fire-God. Tomorrow a fire will break out

in your

house. Hurry home at once to arrange your affairs and save what you

can!"

Frightened, the man faced his horses about and drove home as fast as he

could.

All that he possessed in the way of treasures, clothes and jewels, he

removed

from the house. And, when he was about to lie down to sleep, a fire

broke out

on the hearth which could not be quenched until the whole building had

collapsed in dust and ashes. Yet, thanks to the Fire-God, the man had

saved all

his movable belongings.

Note: "The

Fire-God" (comp. with No. 15).

The Holy Southern Mountain is Sung-Schan in Huan. The Fiery Star is

Mars. The

constellations of the southern quarter of the heavens are grouped by

the

Chinese as under the name of the "Red Bird." The "land of the

four rivers" is Sitehuan, in the western part of present-day China.

XXIV

THE THREE

RULING GODS

THERE

are

three lords: in heaven, and on the earth and in the waters, and they

are known

as the Three Ruling Gods. They are all brothers, and are descended from

the

father of the Monk of the Yanktze-Kiang. When the latter was sailing on

the

river he was cast into the water by a robber. But he did not drown, for

a

Triton came his way who took him along with him to the dragon-castle.

And when

the Dragon-King saw him he realized at once that there was something

extraordinary about the Monk, and he married him to his daughter.

From their

early youth his three sons showed a preference for the hidden wisdom.

And

together they went to an island in the sea. There they seated

themselves and

began to meditate. They heard nothing, they saw nothing, they spoke not

a word

and they did not move. The birds came and nested in their hair; the

spiders

came and wove webs across their faces; worms and insects came and

crawled in

and out of their noses and ears. But they paid no attention to any of

them.

After they

had meditated thus for a number of years, they obtained the hidden

wisdom and

became gods. And the Lord made them the Three Ruling Gods. The heavens

make

things, the earth completes things, and the waters create things. The

Three

Ruling Gods sent out the current of their primal power to aid in

ordering all

to this end. Therefore they are also known as the primal gods, and

temples are

erected to them all over the earth.

If you go

into a temple you will find the Three Ruling Gods all seated on one

pedestal.

They wear women's hats upon their heads, and hold scepters in their

hands, like

kings. But he who sits on the last place, to the right, has glaring

eyes and

wears a look of rage. If you ask why this is you are told: "These three

were brothers and the Lord made them the Ruling Gods. So they talked

about the

order in which they were to sit. And the youngest said: 'To-morrow

morning, before

sunrise, we will meet here. Whoever gets here first shall have the seat

of

honor in the middle; the second one to arrive shall have the second

place, and

the third the third.' The two older brothers were satisfied. The next

morning,

very early, the youngest came first, seated himself in the middle

place, and

became the god of the waters. The middle brother came next, sat down on

the

left, and became the god of the heavens. Last of all came the oldest

brother.

When he

saw that his brothers were already sitting in their places, he was

disgusted

and yet he could not say a word. His face grew red with rage, his

eyeballs

stood forth from their sockets like bullets, and his veins swelled like

bladders. And he seated himself on the right and became god of the

earth. The

artisans who make the images of the gods noticed this, so they always

represent

him thus.

Note: "The

Three Ruling Gods" is set down

as told by the people. It is undoubtedly a version of the Indian

Trimurti. The

meaning of the terrible appearance of the third godhead, evidently no

longer

understood by the people, points to Siva, and has given rise to the

fairy-tale

here told. As regards the Monk of the Yangtze-Kiang, comp. with No. 68.

XXV

A LEGEND

OF CONFUCIUS

WHEN

Confucius came to the earth, the Kilin, that

strange beast which is the prince of all four-footed animals, and only

appears

when there is a great man on earth, sought the child and spat out a

jade

whereon was written: "Son of the Water-crystal

you are destined to become an uncrowned king!" And Confucius grew up,

studied diligently, learned wisdom and came to be a saint. He did much

good on

earth, and ever since his death has been reverenced as the greatest of

teachers

and masters. He had foreknowledge of many things. And even after he had

died he

gave evidence of this.

Once, when

the wicked Emperor Tsin Schi Huang had conquered all the other

kingdoms, and

was traveling through the entire empire, he came to the homeland of

Confucius.

And he found his grave. And, finding his grave, he wished to have it

opened and

see what was in it. All his officials advised him not to do so, but he

would

not listen to them. So a passage was dug into the grave, and in its

main

chamber they found a coffin, whose wood appeared to be quite fresh.

When struck

it sounded like metal. To the left of the coffin was a door, which led

into an

inner chamber. In this chamber stood a bed, and a table with books and

clothing, all as though meant for the use of a living person. Tsin Schi

Huang

seated himself on the bed and looked down. And there on the floor stood

two

shoes of red silk, whose tips were adorned with a woven pattern of

clouds. A

bamboo staff leaned against the wall. The Emperor, in jest, put on the

shoes,

took the staff and left the grave. But as he did so a tablet suddenly

appeared

before his eyes on which stood the following lines:

O'er

kingdoms six Tsin Schi Huang his army led,

To

ope my

grave and find my humble bed;

He

steals

my shoes and takes my staff away

To

reach Shakiu — and his last earthly

day!

Tsin

Schi

Huang was much alarmed, and had the grave closed again. But when he

reached

Schakiu he fell ill of a hasty fever of which he died.

Note: The

Kilin

is an okapi-like legendary beast of

the most perfected kindness, prince of all the four-footed animals. The

"Water-crystal"

is the dark Lord of the North, whose element is water and wisdom, for

which

last reason Confucius is termed his son. Tsin Schi Huang (B.C. 200) is

the burner of

books and reorganizer of China famed in history. Schakiu (Sandhill) was

a city

in the western part of the China of that day.

XXVI

THE GOD OF

WAR

THE

God of

War, Guan Di, was really named Guan Yu. At the time when the rebellion

of the

Yellow Turbans was raging throughout the empire, he, together with two

others

whom he met by the wayside, and who were inspired with the same love of

country

which possessed him, made a pact of friendship. One of the two was Liu

Be,

afterward emperor, the other was named Dschang Fe. The three met in a

peach-orchard and swore to be brothers one to the other, although they

were of

different families. They sacrificed a white steed and vowed to be true

to each

other to the death.

Guan Yu

was faithful, honest, upright and brave beyond all measure. He loved to

read

Confucius's "Annals of Lu," which tell of the rise and fall of

empires. He aided his friend Liu Be to subdue the Yellow Turbans and to

conquer

the land of the four rivers. The horse he rode was known as the Red

Hare, and

could run a thousand miles in a day. Guan Yu had a knife shaped like a

half-moon which was called the Green Dragon. His eyebrows were

beautiful like

those of the silk-butterflies, and his eyes were long-slitted like

the eyes of the Phenix. His face was

scarlet-red in color, and his beard so long that it hung down over his

stomach.

Once, when he appeared before the emperor, the latter called him Duke

Fair-beard, and presented him with a silken pocket in which to place

his beard.

He wore a garment of green brocade. Whenever he went into battle he

showed

invincible bravery. Whether he were opposed by a thousand armies or by

ten

thousand horsemen — he attacked them as though they were merely air.

Once the

evil Tsau Tsau had incited the enemies of his master, the Emperor, to

take the

city by treachery. When Guan Yu heard of it he hastened up with an army

to

relieve the town. But he fell into an ambush, and, together with his

son, was

brought a captive to the capital of the enemy's land. The prince of

that

country would have been glad to have had him go over to his side; but

Guan Yu

swore that he would not yield to death himself. Thereupon father and

son were

slain. When he was dead, his

horse Red Hare

ceased to eat and died. A faithful captain of his, by name of Dschou

Dsang, who

was black-visaged and wore a great knife, had just invested a fortress

when the

news of the sad end of the duke reached him. And he, as well as other

faithful

followers would not survive their master, and perished.

At the

time a monk, who was an old compatriot and acquaintance of Duke Guan

was living

in the Hills of the Jade Fountains. He used to walk at night in the

moonlight.

Suddenly

he heard a loud voice cry down out of the air: "I want my head back

again!"

The monk

looked up and saw Duke Guan, sword in hand, seated on his horse, just

as he

appeared while living. And at his right and left hand, shadowy figures

in the

clouds, stood his son Gann Ping and his captain, Dschou Dsang.

The monk

folded his hands and said: "While you lived you were upright and

faithful,

and in death you have become a wise god; and yet you do not understand

fate! If

you insist on having your head back again, to whom shall the many

thousands of

your enemies who lost their lives through you appeal, in order to have

life

restored to them?"

When he

heard this the Duke Guan bowed and disappeared. Since that time he has

been

without interruption spiritually active. Whenever a new dynasty is

founded, his

holy form may be seen. For this reason temples and sacrifices have been

instituted for him, and he has been made one of the gods of the empire.

Like

Confucius, he received the great sacrifice of oxen, sheep and pigs. His

rank

increases with the passing of centuries. First he was worshiped as

Prince Guan,

later as King Guan, and then as the great god who conquers the demons.

The last

dynasty, finally, worships him as the great, divine Helper of the

Heavens. He

is also called the God of War, and is a strong deliverer in all need,

when men

are plagued by devils and foxes. Together with Confucius, the Master of

Peace,

he is often worshiped as the Master of War.

Note: The

Chinese God of War is a historical

personality from the epoch of the three empires, which later joined the

Han

dynasty, about 250 A. D. Liu Be founded the "Little Han dynasty" in

Setchuan, with the aid of Guan Yu and Dschang Fe. Guan Yu or Guan Di,

i. e.,

"God Yuan," has become one of the most popular figures in Chinese

legend in the course of time, God of War and deliverer in one and the

same

person. The talk of the monk with the God Guan Di in the clouds is

based on the

Buddhist law of Karma. Because Guan Di — even though his motives might

be

good — had slain

other men, he must

endure like treatment at their hands, even while he is a god.

|