| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2012 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

IX

DON'T LOSE SIGHT OF THESE IMPORTANT DETAILS

ONE of the first things people notice in our house is the floors. It is only recently that modern adaptations of old-fashioned plank floors were made available by floor manufacturers. Now it is possible to get wide boards chemically treated and rabbited on the under side to prevent warping, which look exactly like plank floors laid 200 years ago. These floors are usually oak, laid random widths from five to ten inches and apparently pinned down with oak or walnut pins. As a matter of fact they are nailed, the oak pins being merely countersunk over a screw head. In some old houses you occasionally see butterflies, either of brass or wood, imbedded between the wider boards to prevent warping. We had fully intended to have a few butterflies, but frankly none of the carpenters who built my house could be entrusted with a job so delicate as fitting in a tiny butterfly and gluing it down. At the same time, it is a job that any intelligent twelve-year-old boy scout should be able to do with his scout knife. A few butterflies are one of those "some day" jobs that I hope to do for myself. In old houses the floors were frequently laid with noble, old, wrought-iron nails with heads projecting above the boards. While that would have been entirely authentic, like the tallow dip and the horse trough, it wouldn't have been so acceptable, day in and day out. If you have ever stepped on an elusive collar button in the dark you would lose your enthusiasm for projecting nail heads. But plank flooring or wide boards painted, or spatter-dashed even, if they are soft wood, are almost necessary to preserve the spirit of early America in reproduction of houses. Before the days of carpets and with scanty rugs, either animal skins or hook rugs, more floor was left exposed than in later days. Frequently there were no rugs whatever. Sometimes floors were sanded, especially Dutch houses. But don't let anyone tell you that Oriental or as they were formerly called, Turkey rugs, are not in keeping with your period house. Oriental rugs always have been and always will be so intrinsically beautiful that, as Diamond Jim Brady used to say about his ostentatious display of diamonds: "I notice that them that has 'em, shows 'em." Oriental rugs were popular in Europe early in 1700. Naturally, they also found their way to the better homes of America to lend a note of color and cheer. Mrs. Benjamin Franklin in writing to her husband then in London in 1765 said: "In the parlour is a Scotch carpet which has had much fault found with it, if you could meet with a Turkey carpet, I should like it." Oriental rugs are older than hook rugs. But when bits of rags or cloth sewed together could be made into a satisfactory floor covering by the thrifty New England housewife, naturally hook rugs and rag carpets were far more common. The present fad for hook rugs is great. It was inevitable after the Brussels carpet epidemic of the Victorian era. The period home builder should give a lot of thought to his floors. With the rough neck plank flooring, rugs are merely an incidental. You will be so fascinated with the early floors with grooved open joints and pegs that you will even begrudge the occasional rug to cover it. The floors of this type were undoubtedly influenced by the construction of ship decks. The first settled portions of New England were naturally near the coast, and ship carpenters were also house carpenters. The American wing of the Metropolitan Museum is the final word of authority in the traditions and atmosphere of early houses. All the rooms they have restored or moved bodily to this shrine, with one exception, have plank floors laid random widths.

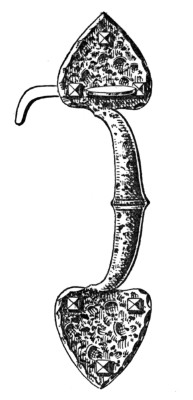

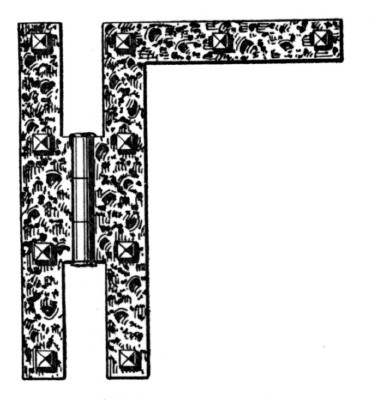

We Used These Old Fashioned Thumb Latches Wherever We Had Batten Doors.  A Typical "H.L." Hinge Which is a Feature of so Many Old Houses. They are also Called "Heavenly Love" or "Lord's House" Hinges and are Supposed to Keep Out Witches, Especially When Combined with a Four Panel Door Which Forms a Cross with the Upper Panels.

All of our ceilings are sand finished in the natural color. This finish used to be called scoured, — the kind that dries to a pleasing gray and doesn't require paint or kalsomine. Some of the earliest houses had this rough textured finish. It was crudely done then and shows prominent trowel marks. Our side walls are smooth because we planned to use wall paper for the entire house except the kitchen, bath and lavatory. When you start out on a quest to select wall papers for an early American house, you are in for a fascinating adventure. The assortment is bewildering. It ranges from stately old vases and castles and wonderful pools with swans and lovers, to weird and garish flower clusters with color combinations that must have been awful to look at the morning after. There is no escaping old-fashioned wall papers. You see them in every store where wall paper is sold. They seem to dominate the industry to-day. Many of them are as pictorial as a tabloid newspaper. Stage coaches, hunting scenes, old inns and animals. Perhaps the early settlers felt about their wall papers as did the man who married the tattooed woman — if they got tired of their house, they could look at the pictures.

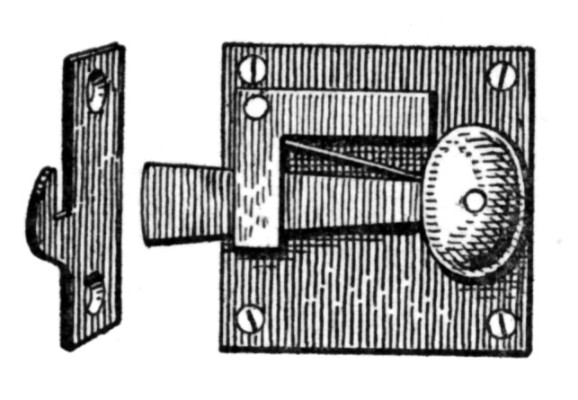

These Little Cupboard Catches with Brass Knobs are Exact Reproductions of Original Hand-made Hardware.  The Reverse Side of a Thumb-latch Which has Continued Practically Without Change in Design for 200 Years.

The only way to describe many of these papers is by the word "quaint," because they are not beautiful. Any wall paper should be an accessory to a room to-day — not the whole show. Therefore there is nothing that will display your taste, good or bad, more than your choice of papers. Wall papers of this type will be expensive. Three to five dollars a roll is not uncommon. Apparently the manufacturers charge all the traffic will bear without reference to initial cost. So would you or I if we had the chance. Don't economize on wall papers. They will be the finishing touch to your home. Early wall papers are just what a period house should have. ''Stampt and Roll Papers for rooms" were freely advertised in the New England Journal as early as 1730. They were sold by booksellers. Some of the first were hand-painted in China on canvas. A letter written in 1738 by Thomas Hancock, uncle of the John Hancock whose signature dominates the Declaration of Independence, gave most explicit directions to a London stationer as to the kind of wall paper he wanted for his house. There were to be ''Birds flying here and there with some landskip at the bottom. Peacocks, Macoys, Squirrel, Monkys, Fruit and Flowers, etc." While these designs were not all for one room, they prove that we can go as far as we like in wall papers without violating the code of our ancestors.

For Our Corner Closets in the Dining Room and also Our Book Cases, We Used this Little Catch with a Brass Knob. These are Perfect Copies of Similar Catches Found in Cape Cod.

In a report to Congress in 1791, Alexander Hamilton, then Secretary of the Treasury, stated that "paper hangings is a branch of manufacture in which respectable progress has been made in America." So at the close of the eighteenth century we were well started on making wall papers for ourselves and were no longer dependent upon England.

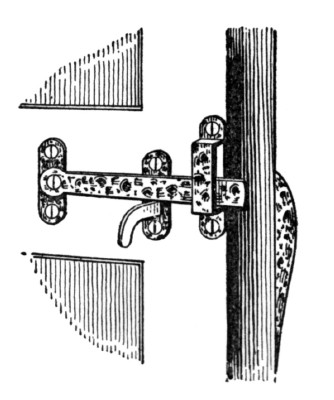

The Type of Hinges We Used Throughout the House. Modern Doors Have "Loose Pin Butts" Which are a Decided Improvement. We Painted These Hinges the Same Color as the Doors and Trim.

Our woodwork is painted an ivory white. The idea was to make it appear like white paint with the patina of age. While it is also enameled over a flat coat, the enamel is of the egg shell variety and does not appear shiny. Either by accident or design, the effect the painter obtained is very similar to that found in old houses. Where a house is paneled in natural pine wood, nothing should be done to the woodwork but to give it a slight coat of boiled linseed oil to remove the new look of the wood. But most old houses were painted and we followed their example as the most practical and inexpensive method. While none of our wall paper is flamboyant or garish, it does unmistakably look old-fashioned. The patterns are of the kind which you almost forget about after they are hung — which, in the final analysis, should be the test of the right kind of wall paper. One of the most important accessories of an early home is appropriate hardware — watch your step on this. The garish hardware common to-day seems to be hard to kill. "Bigger and brassier" is still the motto of lots of people. Colonial hardware is dainty and unobtrusive, small brass knobs, interesting little key plates, graceful butterfly hinges.

Another Type of Hinge, A Modification of H.L. Hinges Which Were Used on Small Cupboards.   These are both Old Houses. The Upper One is about 100 years older than the lower one, which has been restored and modernized.

Wrought-iron latches and H.L. hinges were of necessity heavier and cruder than brass, but even they possess a grace and charm and even a sort of slenderness. Early hardware was hand made. It is true that there were iron foundries in America shortly after the colonists came, but the first job of these foundries was to make the big iron kettles to boil down the maple sap and scald the hogs and to produce a multitude of heavy metal pieces beyond a local blacksmith's equipment. But with his forge and anvil he could make the hardware and nails necessary for house-building. Ready made hardware did not really become established until the Revolution. Before then foundries and blast furnaces were kept reasonably busy on cannon and cannon balls. Some of the old village smithies are still to be found in New England. The ''spreading chestnut tree" is gone. The “mighty man" who presides over the smithy usually has two signs — ''flats fixed" and "ice cold tonics." He can rarely speak English. To him, Myles Standish is the name of a good five-cent cigar. Don't go to him for your early hardware. Several of our leading hardware manufacturers make authentic reproductions so accurately that it would require an expert to tell the difference. It is a positive joy to find old black or brass rim locks with big brass keys, door knockers, foot scrapers, fire dogs and andirons, exact copies of original pieces. My hat is off to these manufacturers who have kept the faith. You can find their advertisements in the house-building magazines. A word about the cost of hardware. Most contractors “lump sum" this when they make an estimate. If they had guessed at my hardware, they would have been in the red about fifty per cent. It is far safer to select your hardware, every last piece of it, either from a catalog or from the actual pieces, and then see to it that the catalog numbers are included in your specifications. The so-called ''H.L" hinges which are sometimes known as ''Lord's House" or "Heavenly Love" hinges are a noticable feature of early houses. They were said to keep the sorcery of witchcraft out of the house. The form of the cross in early doors was another symbol alleged to have the same effect, just as the blood on the lintels and door posts preserved the Children of Israel from harm during the passover just before their flight from Egypt. By the way, there does not seem to be any authentic record that witches were ever burned alive by our Puritan ancestors in Salem. They were either hanged or crushed with logs. I was glad to know that. It would seem incredible that people who built such attractive houses could be so inefficient as to burn old ladies alive. All the “witch finder" had to do was to fell a tree on her unsuspecting head while she sat knitting. Then he would not only save a lot of fire-wood but probably gain enough to keep him warm half the winter.

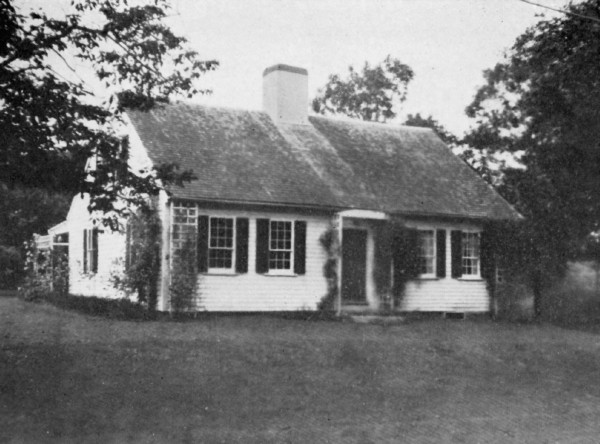

The

home of one of

Salem's most successful witches has a central chimney. I wonder if

she also had H.L. hinges on her cupboard where she kept the

ingredients of her cauldron — wool of bat and tongue of dog adder's fork and blind worm's sting lizard's leg and howlet's wing. The method of lighting early houses, like the houses themselves, when lighted, is somewhat shrouded in gloom. The most primitive lights were pine knots or logs blazing in the fireplace. It has been recorded that Abraham Lincoln learned to read by this fitful method of illumination. Judging from the standards of present day statesmen, it might be well to educate some of our future presidents by the same method. For portable lights, the first were the so-called Betty lamps of iron or brass. They were pear-shaped affairs with a spout and a rod ending in a down-turned spike to stick in a beam. Such lamps were common even as far back as the Roman days — You have seen them in pictures of ''the wise and foolish virgins." Betty lamps burned oil or tallow by means of a wick which extended over the spout. Betty lamps were sometimes used to lower into the kettles to examine their contents. Rush lights were also used, the rush being held by a crude iron holder, the progenitor of the candlestick. Candlesticks were only used upon special occasions. The Puritans soon discovered that the bayberry, common to Cape Cod, yielded a green wax that could be fashioned into candles and burned. Candles of this kind are still sold to tourists. These candles burn with a spicy aromatic odor and are a delightful souvenir of a visit to New England. In many New England houses, where tradition holds a place, you will still see on Christmas Eve a long tapering bayberry candle burning in a window, a symbol of the Star of Bethlehem which guided the wise men to the cradle of the Savior. It is a beautiful custom. By 1700, the use of candles became common among the well-to-do, and candlesticks of the most graceful types fashioned in brass, pewter and silver began to appear. Early candlesticks of this type are priceless. For outside use, a sort of crude lantern with a pointed top and punched with holes burned whale oil or candles. "Genuine" antique lanterns of this type are sold by the thousand to tourists who visit antique shops. A big factory somewhere must be kept busy to supply the demand. Candle-stands where a group of candles were burned came in about 1750. They were wrought iron with brass or pewter mountings. Counterparts of these now known as Colonial bridge lamps are sold in every department store. The legs, frequently a tripod, were undoubtedly influenced by similar legs which were common on tip tables of that period. Even in 1734, the New England Yankees were imitating genuine bayberry candles by coloring tallow, beeswax or spermaceti with verdigris, the green oxide that forms on copper. As this type of candle lacked the aromatic odor of genuine bayberry, and as the coloring matter was poisonous, the buyer of candles who patronized a stranger had to exercise considerable caution to see that the product wasn't bootleg. Even before kerosene was discovered, chandeliers were common. Many of them are exquisite. Glass lustres burning spermaceti candles (obtained from the sperm whale) were found in the finest houses. The glass pendants and hurricane bell-shaped shades, designed to keep the candle from blowing out, are two of the most alluring lighting fixtures that have come down to us from the early days. There are many possible examples of beautiful lighting fixtures, wired for current, that manufacturers could reproduce, but for some unknown reason they haven't done it. When you come to select your lighting fixtures you are in for it. True, there are plenty of side fixtures crudely made of pewter or an imitation, but appropriate central fixtures are almost unknown to the trade. This type of fixture offers a wonderful opportunity to the manufacturer who will approach his job with the same degree of enthusiasm that has been followed by the reproducer of early hardware and early furniture. We are still under the influence of the Victorian period in early lighting fixtures. Manufacturers seem to feel that they must make something to look like a gas chandelier, just as early motor car makers thought that a horseless carriage should look like a buggy minus the whipsocket and whiffletree. After searching New York over for an appropriate central fixture for our dining room, we finally had one made to order. It is a combination of hurricane shades, brass eagle and colonial rosettes. While it has been greatly admired, you would search a 1750 house in vain to find its counterpart. It is nearer 1800. But why bring that up? With the vogue for bridge and table lamps, to say nothing of electrical devices of all kinds, don't economize on baseboard outlets. Some day you will need them for orange squeezers, vacuum cleaners, percolators, vibrators, electric clocks. We have fifteen baseboard outlets in our living room and sun room alone, and a dozen in the kitchen. If you have a feeling that you may need a baseboard outlet, put it in. They cost very little extra when a house is being built. They cost a whale of a lot to put in later. Remember the radio. That will require two, one outlet for electricity and another plate labeled ''antenna and ground." It is a small matter to extend a lead-in wire through a partition up to the attic. Even if your present radio doesn't require an aerial, maybe your television set in 1935 will. No one should consider building a house of any type to-day without insulation. Insulation can't be expected to take care of heat leaks that occur around windows poorly fitted, or with foundations that permit the wind a chance to sweep under floors, but it is remarkable what suitable insulation can accomplish in keeping in heat and keeping out cold. House-building magazines are filled with advertisements of insulating material. Two centuries before house-building magazines were thought of, colonists appreciated the value of filling the spaces between the walls and siding with soft brick, sea weed, leaves, straw or anything that would do the trick. Some houses even piled fresh stable manure around the foundations in winter. Many old houses are apparently sided with shingles or clapboards, but actually are brick laid up in clay joints. Modern insulation is bound to be a confusing subject for the house-builder. There are many new products made of cork, felt, wood fibre, sugar cane, mineral wool, asbestos, flax, hair, jute, gypsum. There is no question that insulation is a good thing. It may even save its initial cost in fuel in a few years, to say nothing of the greatest comfort it provides both summer and winter. Every argument that applies to keeping in our bodily heat with red flannel undershirts or Russian Sable coats applies with equal force to keeping furnace heat in. One exceedingly important source of heat loss is through the roof. It is estimated at twenty-five per cent. But whatever it is, you can always tell when a house is leaking heat by looking at the roof after a snowfall. When the snow quickly melts, someone is paying for it in fuel. But which insulator to use — that is the question. Or at least that was my question as I wrote my own specifications. I discovered that the Bureau of Standards at Washington published a bulletin on insulators which spoke right out in meeting and mentioned names. This gave the rating of practically all insulation material scaled on a chart and called ''internal conductivity." The lower the figure of conductivity the better the insulator. They are listed by Uncle Sam with all the claims of advertising left out. It made my choice easy. As a matter of fact, I used two types of insulation, one on the studding to be plastered on ultimately to form the walls, the other came in sheets and was tacked between the walls. In addition to insulation, our house, being on an exposed location, has weather strips on the outside doors and windows. While we are on this subject of insulation, it is important to look after heat leaks between the foundations and the house frame. That is where a lot of cold can get in. In our cellar the heating contractor made so excellent a job of protecting all hot-water pipes with asbestos covering, that the cellar is positively cold. That, I'm afraid, is going to be a real problem, as it means the end of my cellar workroom where I planned to fuss with old furniture, tinker with tools, and escape from the True Story Radio Hour. An easy method of heating our cellar would be ceiling radiators such as we now have in the laundry. Possibly I will use an old Franklin stove I have my eye on. That is an example of an antique that would be both useful and interesting. But to put the old Franklin stove in the living room as an ornament tied with red ribbon would be as much of an eyesore as a gilded curry comb I once had painted with lilies of the valley. Don't forget the insulation especially, if you ever expect to sell your house. That is going to be one of the first questions the buyer is going to ask in a few years when coal gets to be $20. a ton, or the price of oil goes up. One interesting and unusual feature to include in your early American house is the type of built-in cupboards and closets so common in old houses. One of the earliest of those is the corner closet of unfinished pine with curved shelves above and a cupboard below. Some of them had a sort of conch shell or sunburst back beautifully carved and sometimes painted. These closets in the older houses were usually built in, but were also separate pieces of furniture. There are also closets under staircases and by the sides of fireplaces in paneled rooms. Sometimes they were merely hinged panels more or less concealed like the secret compartments in old desks. In a house at Duxbury there is a kitchen cupboard by the side of a huge fireplace, which, when the side is removed, discloses a secret ladder to gain access to the attic. In this house two early patriots were fed and watered for several months while the soldiers of George the Third were keeping daily watch over the house. There is no trick to make closets look old. All you need are batten doors and old-fashioned hardware. The use of H.L. hinges is always a safe expedient if it isn't overdone. Even kitchen closets can have character. Before I ran across the 130-year-old fireplace which is now a part of the house, we had planned to have two such closets one on each side of the fireplace. One was to be just wide enough to house two bridge tables on end, and the other was to serve as a wood closet with a sort of elevator arrangement to lift a basket of wood from the cellar. |