| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2014 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

MY FRIENDS

Two friends I

have, and close akin are they.

For both are free And wild and proud, full of the ecstasy Of life untrammeled; living, day by day, A law unto themselves; yet breaking none Of Nature's perfect code. And far afield, remote from man's abode, They roam the wilds together, two as one. Yet, one's a dog — a wisp of silky hair, Two sharp black eyes, A face alert, mysterious and wise, A shadowy tail, a body lithe and fair. And one's a man — of Nature's work the best, A heart of gold, A mind stored full of treasures new and old, Of men the greatest, strongest, tenderest. They love each other — these two friends of mine — Yet both agree In this — with that pure love that's half divine They both love me. THE DOG AND THE MAN THERE is no time to tell

of all the bays we explored; of

Holkham Bay, Port Snettisham, Tahkou Harbor; all of which we rudely

put on the

map, or at least extended the arms beyond what was previously known.

Through

Gastineau Channel, now famous for some of the greatest quartz mines and

mills

in the world, we pushed, camping on the site of what is now Juneau, the

capital

city of Alaska. An interesting bit of

history is to be recorded here.

Pushing across the flats at the head of the bay at high tide the next

morning

(for the narrow, grass-covered flat between Gastineau Channel and

Stevens

Passage can only be crossed with canoes at flood tide), we met two old

gold

prospectors whom I had frequently seen at Wrangell — Joe Harris and

Joe

Juneau. Exchanging greetings and news, they told us they were out from

Sitka on

a leisurely hunting and prospecting trip. Asking us about our last

camping

place, Harris said to Juneau, "Suppose we camp there and try the gravel

of

that creek." These men found placer

gold and rock "float" at

our camp and made quite a clean-up that fall, returning to Sitka with a

"gold-poke" sufficiently plethoric to start a stampede to the new

diggings. Both placer and quartz locations were made and a brisk

"camp" was built the next summer. This town was first called

Harrisburg for one of the prospectors, and afterwards Juneau for the

other.

The great Treadwell gold quartz mine was located three miles from

Juneau in

1881, and others subsequently. The territorial capital was later

removed from

Sitka to Juneau, and the city has grown in size and importance, until

it is one

of the great mining and commercial centers of the Northwest. Through Stevens Passage

we paddled, stopping to preach to

the Auk Indians; then down Chatham Strait and into Icy Strait, where

the

crystal masses of Muir and Pacific glaciers flashed a greeting from

afar. We

needed no Hoonah guide this time, and it was well we did not, for both

Hoonah

villages were deserted. The inhabitants had gone to their hunting,

fishing or

berry-picking grounds. At Pleasant Island we

loaded, as on the previous trip, with

dry wood for our voyage into Glacier Bay. We were not to attempt the

head of

the bay this time, but to confine our exploration to Muir Glacier,

which we had

only touched upon the previous fall. Pleasant Island was the scene of

one of

Stickeen's many escapades. The little island fairly teemed with big

field mice

and pine squirrels, and Stickeen went wild. We could hear his shrill

bark, now

here, now there, from all parts of the island. When we were ready to

leave the

next morning he was not to be seen. We got aboard as usual, thinking

that he

would follow. A quarter of a mile's paddling and still no little black

head

could be discovered in our wake. Muir, who was becoming very much

attached to

the little dog, was plainly worried. "Row back," he said. So we rowed back and

called, but no Stickeen. Around the

next point we rowed and whistled; still no Stickeen. At last,

discouraged, I

gave the signal to move off. So we rounded the curving shore and pushed

towards

Glacier Bay. At the far point of the island, a mile from our camping

place, we

suddenly discovered Stickeen away out in the water, paddling calmly

and confidently

towards our canoe. How he had ever got there I cannot imagine. I think

he must

have been taking a long swim out on the bay for the mere pleasure of

it. Muir

always insisted that he had listened to our discussion of the route to

be

taken, and, with an uncanny intuition that approached clairvoyance,

knew just

where to head us off. When we took him aboard

he went through his usual

performance, making his way, the whole length of the canoe, until he

got under

Muir's legs, before shaking himself. No protests or discipline availed,

for

Muir's kicks always failed of their pretended mark. To the end of his

acquaintance with Muir, he always chose the vicinity of Muir's legs as

the

place to shake himself after a swim. At Muir Glacier we spent

a week this time, making long trips

up the mountains that overlooked the glacier and across its surface.

On one

occasion Muir, with the little dog at his heels, crossed entirely in a

diagonal

direction the great glacial lake, a trip of some thirty miles, starting

before

daylight in the morning and not appearing at camp until long after

dark. Muir

always carried several handkerchiefs in his pockets, but this time he

returned

without any, having used them all up making moccasins for Stickeen,

whose feet

were cut and bleeding from the sharp honeycomb ice of the glacial

surface. This

mass of ice is so vast and so comparatively still that it has but few

crevasses, and Muir's day for traversing it was a perfect one — warm

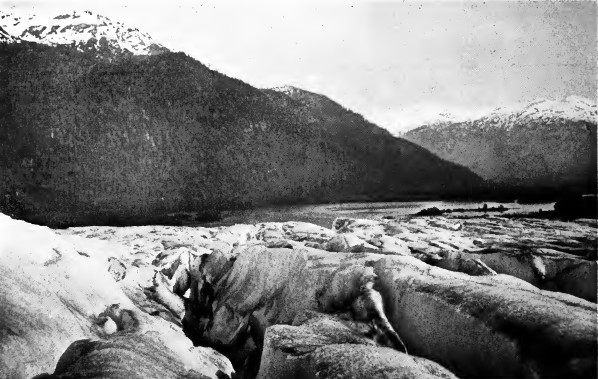

and sunny.  THE FRONT OF MUIR GLACIER We could understand the constant breaking off and leaping up and smashing down of the ice, and the formation of the great mass of bergs Shortly before we left

Muir Glacier, I saw Muir furiously

angry for the first and last time in my acquaintance with him. We had

noticed

day after day, whenever the mists admitted a view of the mountain

slopes,

bands of mountain goats looking like little white mice against the

green of the

high pastures. I said to Joe, the hunter, one morning: "Go up and get

us

a kid. It will be a great addition to our larder." He took my breech-loading

rifle and went. In the afternoon

he returned with a fine young buck on his shoulders. While we were

examining

it he said: "I picked the fattest and

most tender of those that I

killed." "What!" I exclaimed, "did

you kill more than

this one?" He put up both hands with

fingers extended and then one

finger: "Tatlum-pe-ict (eleven),"

he replied. Muir's face flushed red,

and with an exclamation that was as

near to an oath as he ever came, he started for Joe. Luckily for that

Indian he

saw Muir and fled like a deer up the rocks, and would not come down

until he

was assured that he would not be hurt. I shared Muir's indignation and

would

have enjoyed seeing him administer the richly deserved thrashing. Muir had a strong

aversion to taking the life of any animal;

although he would eat meat when prepared, he never killed a wild

animal;

even the rattlesnakes he did not molest during his rambles in

California.

Often his softness of heart was a source of some annoyance and a great

deal of

astonishment to our natives; for he would take pleasure in rocking the

canoe

when they were trying to get a bead on a flock of ducks or a deer

standing on

the shore. On leaving the mouth of

Glacier Bay we spent a week or more

exploring the inlets and glaciers to the west. These days were rainy

and cold.

We groped blindly into unknown, unmapped, fog-hidden fiords and

bayous,

exploring them to their ends and often making excursions to the

glaciers above

them. The climax of the trip,

however, was the last glacier we

visited, Taylor Glacier, the scene of Muir's great adventure with

Stickeen. We

reached this fine glacier in the afternoon of a very stormy day. We

were

approaching the open Pacific, and the saanah, the southeast rain-wind,

was

howling through the narrow entrance into Cross Sound. For twenty miles

we had

been facing strong head winds and tidal waves as we crept around rocky

points

and along the bases of dizzy cliffs and glacier-scored rock-shoulders.

We were

drenched to the skin; indeed, our clothing and blankets had been

soaking wet for

days. For two hours before we turned the point into the cozy harbor in

front of

the glacier we had been exerting every ounce of our strength; Lot in

the stern

wielding his big steering paddle, now on this side, now on that,

grunting with

each mighty stroke, calling encouragement to his crew, "Ut-ha, ut-ha!

hlitsin! hlitsin-tin! (pull, pull, strong, with strength!)"; Joe and

Billy

rising from their seats with every stroke and throwing their whole

weight and

force savagely into their oars; Muir and I in the bow bent forward with

heads

down, butting into the slashing rain, paddling for dear life; Stickeen,

the

only idle one, looking over the side of the boat as though searching

the

channel and then around at us as if he would like to help. All except

the dog

were exhausted when we turned into the sheltered cove. While the men pitched the

tents and made camp Muir and I

walked through the thick grass to the front of the large glacier, which

front

stretched from a high, perpendicular rock wall about three miles to a

narrow

promontory of moraine boulders next to the ocean. "Now, here is something

new," exclaimed Muir, as

we stood close to the edge of the ice. "This glacier is the great

exception. All the others of this region are receding; this has been

coming

forward. See the mighty ploughshare and its furrow!" For the icy mass was

heaving up the ground clear across its

front, and, on the side where we stood, had evidently found a softer

stratum

under a forest-covered hill, and inserted its shovel point under the

hill,

heaved it upon the ice, cracking the rocks into a thousand fragments;

and was

carrying the whole hill upon its back towards the sea. The large trees

were

leaning at all angles, some of them submerged, splintered and ground by

the

crystal torrent, some of the shattered trunks sticking out of the ice.

It was

one of the most tremendous examples of glacial power I have ever seen. "I must climb this

glacier to-morrow," said Muir.

"I shall have a great day of it; I wish you could come along." I sighed, not with

resignation, but with a grief that was

akin to despair. The condition of my shoulders was such that it would

be

madness to attempt to join Muir on his longer and more perilous climbs.

I

should only spoil his day and endanger his life as well as my own. That night I baked a good

batch of camp bread, boiled a

fresh kettle of beans and roasted a leg of venison ready for Muir's

breakfast,

fixed the coffee-pot and prepared dry kindling for the fire. I knew he

would be

up and off at daybreak, perhaps long before. "Wake me up," I

admonished him, "or at least

take time to make hot coffee before you start." For the wind was rising

and the rain pouring, and I knew how imperative the call of such a

morning as

was promised would be to him. To traverse a great, new, living,

rapidly moving

glacier would be high joy; but to have a tremendous storm added to this

would

simply drive Muir wild with desire to be himself a part of the great

drama

played on the glacier-stage. Several times during the

night I was awakened by the

flapping of the tent, the shrieking of the wind in the spruce-tops and

the

thundering of the ocean surf on the outer barrier of rocks. The

tremulous

howling of a persistent wolf across the bay soothed me to sleep again,

and I

did not wake when Muir arose. As I had feared, he was in too big a

hurry to

take time for breakfast, but pocketed a small cake of camp bread and

hastened

out into the storm-swept woods. I was aroused, however, by the

controversy

between him and Stickeen outside of the tent. The little dog, who

always slept

with one eye and ear alert for Muir's movements, had, as usual,

quietly left

his warm nest and followed his adopted master. Muir was scolding and

expostulating

with him as if he were a boy. I chuckled to myself at the futility of

Muir's

efforts; Stickeen would now, as always, do just as he pleased — and he

would

please to go along. Although I was forced to

stay at the camp, this stormy day

was a most interesting one to me. There was an old Hoonah chief camped

at the

mouth of the little river which flowed from under Taylor Glacier. He

had with

him his three wives and a little company of children and grandchildren.

The

many salmon weirs and summer houses at this point showed that it had

been at

one time a very important fishing place. But the advancing glacier

had played havoc with the chief's

salmon stream. The icy mass had been for several years traveling

towards the

sea at the rate of at least a mile every year. There were still silver

hordes

of fine red salmon swimming in the sea outside of the river's mouth.

But the

stream was now so short that the most of these salmon swam a little

ways into

the mouth of the river and then out into the salt water again,

bewildered and

circling about, doubtless wondering what had become of their parent

stream. The old chief came to our

camp early, followed by his squaws

bearing gifts of salmon, porpoise meat, clams and crabs; and at his

command

two of the girls of his family picked me a basketful of delicious wild

strawberries. He sat motionless by my fire all the forenoon, smoking my

leaf

tobacco and pondering deeply. After the noon meal, which I shared with

him, he

called Billy, my interpreter, and asked for a big talk. With all ceremony I made

preparations, gave more presents

of leaf tobacco and hardtack and composed myself for the palaver. After

the

usual preliminaries, in which he told me at great length what a great

man I

was, how like a father to all the people, comparing me to sun, moon,

stars and

all other great things; I broke in upon his stream of compliments and

asked

what he wanted. Recalled to earth he

said: "I wish you to pray to your

God." "For what do you wish me

to pray?" I asked. The old man raised his

blanketed form to its full height and

waved his hand with a magnificent gesture towards the glacier. "Do you

see

that great ice mountain?" "Yes." "Once," he said, "I had

the finest salmon

stream upon the coast." Pointing to a point of rock five or six miles

beyond the mouth of the glacier he continued: "Once the salmon stream

extended far beyond that point of rock. There was a great fall there

and a deep

pool below it, and here for years great schools of king salmon came

crowding

up to the foot of that fall. To spear them or net them was very easy;

they were

the fattest and best salmon among all these islands. My household had

abundance

of meat for the winter's need. But the cruel spirit of that glacier

grew angry

with me, I know not why, and drove the ice mountain down towards the

sea and

spoiled my salmon stream. A year or two more and it will be blotted out

entirely. I have done my best. I have prayed to my gods. Last spring I

sacrificed two of my slaves, members of my household, my best slaves, a

strong

man and his wife, to the spirit of that glacier to make the ice

mountain stop;

but it comes on, and now I want you to pray to your God, the God of the

white

man, to see if He will make the glacier stop!" I wish I could describe

the pathetic earnestness of this old

Indian, the simplicity with which he told of the sacrifice of his

slaves and

the eager look with which he awaited my answer. When I exclaimed in

horror at

his deed of blood he was astonished; he could not understand. "Why, they were my

slaves," he said, "and the

man suggested it himself. He was glad to go to death to help his

chief." A few years after this

our missionary at Hoonah had the

pleasure of baptizing this old chief into the Christian faith. He had

put away

his slaves and his plural wives, had surrendered the implements of his

old

superstition, and as a child embraced the new gospel of peace and

love. He

could not get rid of his superstition about the glacier, however, and

about

eight years afterwards, visiting at Wrangell, he told me as an item of

news

which he expected would greatly please me that, doubtless as a result

of my

prayers, Taylor Glacier was receding again and the salmon beginning to

come

into that stream. At intervals during this

eventful day I went to the face of

the glacier and even climbed the disintegrating hill that was riding on

the

glacier's ploughshare, in an effort to see the bold wanderers; but the

jagged

ice peaks of the high glacial rapids blocked my vision, and the rain

driving

passionately in horizontal sheets shut out the mountains and the upper

plateau

of ice. I could see that it was snowing on the glacier, and imagined

the

weariness and peril of dog and man exposed to the storm in that

dangerous

region. I could only hope that Muir had not ventured to face the wind

on the

glacier, but had contented himself with tracing its eastern side, and

was somewhere

in the woods bordering it, beside a big fire, studying storm and

glacier in

comparative safety. When the shadows of

evening were added to those of the storm

I had my men gather materials for a big bonfire, and kindle it well out

on the

flat, where it could be seen from mountain and glacier. I placed dry

clothing

and blankets in the fly tent facing the camp-fire, and got ready the

best

supper at my command : clam chowder, fried porpoise, bacon and beans,

"

savory meat " made of mountain kid with potatoes, onions, rice and

curry,

camp biscuit and coffee, with dessert of wild strawberries and

condensed milk. It grew pitch-dark before

seven, and it was after ten when

the dear wanderers staggered into camp out of the dripping forest.

Stickeen did

not bounce in ahead with a bark, as was his custom, but crept silently

to his

piece of blanket and curled down, too tired to shake himself. Billy and

I laid

hands on Muir without a word, and in a trice he was stripped of his

wet

garments, rubbed dry, clothed in dry underwear, wrapped in a blanket

and set

down on a bed of spruce twigs with a plate of hot chowder before him.

When the

chowder disappeared the other hot dishes followed in quick succession,

without

a question asked or a word uttered. Lot kept the fire blazing just

right, Joe

kept the victuals hot and baked fresh bread, while Billy and I waited

on Muir. Not till he came to the

coffee and strawberries did Muir

break the silence. "Yon's a brave doggie," he said. Stickeen, who

could not yet be induced to eat, responded by a glance of one eye and a

feeble

pounding of the blanket with his heavy tail. Then Muir began to talk,

and little by little, between sips

of coffee, the story of the day was unfolded. Soon memories crowded for

utterance

and I listened till midnight, entranced by a succession of vivid

descriptions

the like of which I have never heard before or since. The fierce music

and

grandeur of the storm, the expanse of ice with its bewildering

crevasses, its

mysterious contortions, its solemn voices were made to live before me. When Muir described his

marooning on the narrow island of

ice surrounded by fathomless crevasses, with a knife-edged sliver

curving

deeply "like the cable of a suspension bridge " diagonally across it

as the only means of escape, I shuddered at his peril. I held my

breath as he

told of the terrible risks he ran as he cut his steps down the wall of

ice to

the bridge's end, knocked off the sharp edge of the sliver, hitched

across inch

by inch and climbed the still more difficult ascent on the other side.

But when

he told of Stickeen's cries of despair at being left- on the other side

of the

crevasse, of his heroic determination at last to do or die, of his

careful

progress across the sliver as he braced himself against the gusts and

dug his

little claws into the ice, and of his passionate revulsion to the

heights of

exultation when, intoxicated by his escape, he became a living

whirlwind of

joy, flashing about in mad gyrations, shouting and screaming "Saved!

saved!" my tears streamed down my face. Before the close of the story

Stickeen arose, stepped slowly across to Muir and crouched down with

his head

on Muir's foot, gazing into his face and murmuring soft canine words of

adoration to his god.  "We had to make long, narrow tacks and doublings, tracing the edges of tremendous transverse and longitudinal crevasses — beautiful and awful" Not until 1897, seventeen

years after the event, did Muir

give to the public his story of Stickeen. How many times he had written

and rewritten

it I know not. He told me at the time of its first publication that he

had been

thinking of the story all of these years and jotting down paragraphs

and

sentences as they occurred to him. He was never satisfied with a

sentence until

it balanced well. He had the keenest sense of melody, as well as of

harmony,

in his sentence structure, and this great dog-story of his is a

remarkable

instance of the growth to perfection of the great production of a great

master. The wonderful power of

endurance of this man, whom Theodore

Roosevelt has well called a "perfectly natural man," is instanced

by the fact that, although he was gone about seventeen hours on this

day of his

adventure with Stickeen, with only a bite of bread to eat, and never

rested a

minute of that time, but was battling with the storm all day and often

racing

at full speed across the glacier, yet he got up at daylight the next

morning,

breakfasted with me and was gone all day again, with Stickeen at his

heels,

climbing a high mountain to get a view of the snow fountains and upper

reaches

of the glacier; and when he returned after nightfall he worked for two

or three

hours at his notes and sketches. The latter part of this

voyage was hurried. Muir had a wife

waiting for him at home and he had promised to stay in Alaska only one

month.

He had dallied so long with his icy loves, the glaciers, that we were

obliged

to make all haste to Sitka, where he expected to take the return

steamer. To

miss that would condemn him to Alaska and absence from his wife for

another

month. Through a continually pouring rain we sailed by the then

deserted town

of Hoonah, ascended with the rising tide a long, narrow, shallow inlet,

dragged

our canoe a hundred yards over a little hill and then descended with

the

receding tide another long, narrow passage down to Chatham Strait; and

so on to

the mouth of Peril Strait which divided Baranof from Chichagof Island. On the other side of

Chatham Strait, opposite the mouth of

Peril, we visited again Angoon, the village of the Hootz-noos. From

this town

the painted and drunken warriors had come the winter before and

attacked the

Stickeens, killing old Tow-a-att, Moses and another of our Christian

Indians.

The trouble was not settled yet, and although the two tribes had

exchanged some

pledges and promised to fight no more, I feared a fresh outbreak, and

so

thought it wise to pay another visit to the Hootz-noos. As we

approached

Angoon, however, I heard the war-drums beating with their peculiar

cadence,

"turn-turn" — a beat off — "turn-turn, turn-turn." As we

came up to the beach I saw what was seemingly the whole tribe dancing

their

war-dances, arrayed in their war-paint with their fantastic war-gear

on. So

earnestly engaged were they in their dance that they at first paid no

attention

whatever to me. My heart sank into my boots. "They are going back to

Wrangell to attack the Stickeens," I thought, "and there will be

another bloody war." Driving our canoe ashore,

we hurried up to the head chief

of the Hootz-noos, who was alternately haranguing his people and

directing the

dances. "Anatlask," I called,

"what does this mean?

You are going on the warpath. Tell me what you are about. Are you going

back to

Stickeen? " He looked at me vacantly

a little while, and then a grin

spread from ear to ear. It was the same chief in whose house I had seen

the

idiot boy a year before. " Come with me," he said.

He led us into his house

and across the room to where in

state, surrounded by all kinds of chieftain's gear, Chilcat blankets,

totemic

carvings and paintings, chieftain's hats and cunningly woven baskets,

there

lay the body of a stalwart young man wrapped in a button-embroidered

blanket.

The chief silently removed the blanket from the face of the dead. The

skull was

completely crushed on one side as by a heavy blow. Then the story came

out. The hootz, or big brown

bear of that country, is as large

and savage as the grizzly bear of the Rockies. At certain seasons he

is, as the

natives say, "quonsum-sollex" (always mad). The natives seldom

attack these bears, confining their attention to the more timid and

easily

killed black bears. But this young man with a companion, hunting on

Baranof

Island across the Strait, found himself suddenly confronted by an

enormous

hootz. The young man rashly shot him with his musket, wounding him

sufficiently

to make him furious. The tremendous brute hurled his thousand pounds of

ferocity

at the hunter, and one little tap of that huge paw crushed his skull

like an

egg-shell. His companion brought his body home; and now the whole

tribe had

formally declared war on that bear, and all this dancing and painting

and

drumming was in preparation for a war party, composed of all the men,

dogs and

guns in the town. They were going on the warpath to get that bear.

Greatly

relieved, I gave them my blessing and sped them on their way. We had been rowing all

night before this incident, and all

the next night we sailed up the tortuous Peril Strait, going upward

with the

flood, one man steering while the other slept, to the meeting place of

the

waters; then down with the receding tide through the islands, and so on

to

Sitka. Here we met a warm reception from the missionaries, and also

from the

captain and officers of the old man-of-war Jamestown, afterwards used

as a

school ship for the navy in the harbor of San Francisco. Alaska at that time had

no vestige of civil government, no

means of punishing crime, no civil officers except the customs

collectors, no

magistrate or police, — everyone was a law to himself. The only sign

of

authority was this cumbersome sailing vessel with its marines and

sailors. It

could not move out of Sitka harbor without first sending by the monthly

mail

steamer to San Francisco for a tug to come and tow it through these

intricate

channels to the sea where the sails could be spread. Of course, it was

not of

much use to this vast territory. The officers of the Jamestown were

supposed

to be doing some surveying, but, lacking the means of travel, what they

did

amounted to very little. They were interested at

once in our account of the discovery

of Glacier Bay and of the other unmapped bays and inlets that we had

entered.

At their request, from Muir's notes and our estimate of distances by

our rate

of sailing, and of directions from observations of our little compass,

we drew

a rough map of Glacier Bay. This was sent on to Washington by these

officers

and published by the Navy Department. For six or seven years it was the

only

sailing chart of Glacier Bay, and two or three steamers were wrecked,

groping

their way in these uncharted passages, before surveying vessels began

to make

accurate maps. So from its beginning has Uncle Sam neglected this

greatest and

richest of all his possessions. Our little company

separated at Sitka. Stickeen and our

Indian crew were the first to leave, embarking for a return trip to

Wrangell by

canoe. Stickeen had stuck close to Muir,, following him everywhere,

crouching

at his feet where he sat, sleeping in his room at night. When the time

came for

him to leave Muir explained the matter to him fully, talking to and

reasoning

with him as if he were human. Billy led him aboard the canoe by a

dog-chain,

and the last Muir saw of him he was standing on the stern of the canoe,

howling

a sad farewell. Muir sailed south on the

monthly mail steamer; while I took

passage on a trading steamer for another missionary trip among the

northern

tribes. So ended my canoe voyages

with John Muir. Their memory is

fresh and sweet as ever. The flowing stream of years has not washed

away nor

dimmed the impressions of those great days we spent together. Nearly

all of

them were cold, wet and uncomfortable, if one were merely an animal, to

be

depressed or enlivened by physical conditions. But of these so-called

"hardships" Muir made nothing, and I caught his spirit; therefore,

the beauty, the glory, the wonder and the thrills of those weeks of

exploration

are with me yet and shall endure — a rustless, inexhaustible treasure. |