|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

IV

SWORDFISHING IN THE PACIFIC

I ROAM THE SEAS TO FIGHT THE

WHALE,

WITH SWORD I THRUST, I STRIKE WITH TAIL,

BUT WHEN I’M HOOKED I SOUND AND FIGHT

THE LUCKLESS FISHERMAN HALF THE NIGHT.

THE swordfish (Xiphias gladius) of the Pacific is the same fish that is so well known in the Atlantic Ocean. Several thousand of these fish are captured every season during July and August along our coast from Block Island to Halifax, N. S.

The average weight of the swordfish shipped to the Boston market is about 360 pounds, and there is a legend among the fishermen that a fish was once brought in that weighed 750 pounds.

The U. S. Fisheries Commission have never been able to find out where these fish breed. No very small fish have ever been taken along our coast although the Commission did capture a 25 pounder on one occasion. It is known that the fish breed in the Mediterranean, but as they appear there at the same season of the year that they do here this would hardly apply to our fish.

These fish are found in midsummer swimming leisurely along on top of the water apparently sunning themselves. The boatmen steal upon them in power-boats. A fisherman is poised on the bowsprit or bow of the boat supported by a so-called pulpit of iron, and when just over the fish harpoons him. The steel end of the harpoon is driven well home and to it is attached a long strong rope which is coiled in a tub so that it will run free. To the end of the rope a five gallon keg painted white is fastened. This keg usually bears its owner’s or the boat’s name.

The harpooned fish always go to windward, and it used to be quite an undertaking to follow them in the days when sailpower had to be depended on, but the motor-boat has made it easy work.

The swordfish soon tires after sounding deep a few times, and when the tired fish comes to the surface he is lanced and hauled on board.

Great numbers of fish are taken in this manner every season. I heard of one boat that after a fourteen days’ trip divided $5,000 among a crew of five fishermen. The swordfish bring fifteen cents a pound in the Boston market and are excellent eating.

Swordfishing is not carried on as a profession in the Pacific nor is the fish to be found in the market, but swordfishing with a rod and reel has become a sport, and an arduous one, for the members of the Tuna Club at Avalon.

The first fish was taken in 1913, since which time twenty fish have been brought in and weighed. The heaviest qualified fish weighed 465 pounds and the smallest 130 pounds.

Regulation Tuna Club tackle is used—a sixteen-ounce tip five feet or more long and 1,200 feet or more of 24-thread line. The leader is made of strong piano wire doubled.

Two six-foot wires are strung from the hook to a one-inch ring and two wires of the same length join this ring to another one onto which the line is bent. The rings are for the glove-handed boatman to hold on to when he gaffs the fish. Some fishermen use a chain on the hook and a swivel in place of the middle ring but they are not quite trustworthy.

Mr. Boschen, the strongest and most skillful fisherman in the Tuna Club, has fished for swordfish daily from June 1st to October for three years. He has fought some forty odd fish and has landed but eight. He has battled with them for five, eight, and even eleven hours and half through the night. He tells me they really do not wake up until it grows dark. He fought one fish for eleven hours. The fish sounded forty eight times and had to be pumped up and led the launch twenty-nine miles before he was lost owing to the steel hook having cut through the brass chain attached to it.

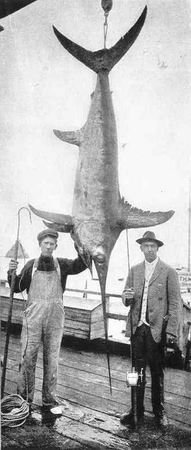

MR. JOHN V. ELIOT AND SWORDFISH

5 hours and 7 minutes

Mr. Boschen thinks they are the greatest fish that swim. They certainly are the most difficult to kill for they have a strength and vitality that are beyond belief. They fight as a heavyweight fighter boxes, for their every move is deliberate and well thought out. The marlin fights quickly and is all over the place; not so the swordfish. He moves as a rule slowly but with great strength and deliberation, yet he is known to be the fastest swimmer of the seas. Now and then, it is said, a crazy fish is hooked and acts quite differently.

The swordfish do not begin to fight until after the first or second hour when they seem to wake up, and a fish has been known to fight for an hour after he had the gaff in him and before he could be securely roped. Once you have a rope around the fish’s tail he is safely captured but not until then.

There were seven swordfish brought in during the eighteen days that I was at Avalon and four of them had been foul-hooked. A 404 pound fish was hooked in the anal fin, the hook having passed from his mouth through his gills in some mysterious manner and fastened in the anal fin. The wire had cut through the gills and after a five hours’ fight the fish had bled to death and sank. He had to be handed up as the rod could not lift the weight. It took three men forty minutes to bring him to the surface tail first. His tail was then roped and he was towed twelve miles to Avalon.

Two fish were brought in wrapped up in the wire leader which had caught the hook and held the fish as in a vise. In both cases the bait was still on the hook.

The swordfish, when he sees the bait, sinks and the first thing he does is to hit the bait a hard blow with his sword. He seems to do this at times from pure viciousness, for he does not always take the bait after hitting it but moves off. He seems to be a poor batsman for he often becomes foul hooked by striking the wire instead of the bait; the wire enwraps his sword and in his struggles he becomes foul hooked.

One fish had been hooked in the anal fin and the wire had been across his mouth which was badly lacerated. If foul hooked in the body and not in the fins the hook usually pulls out as they are a tender-skinned fish.

It is very hard work, the hardest fishing undertaking that I ever indulged in, and I do not advise anyone to undertake it who is not young and strong and who does not weigh at least 180 pounds, yet there are moments in swordfishing that are intensely interesting even for a lightweight.

The Farnum brothers of moving picture fame, both strong men, fought a broadbill for eleven hours. One of them wore a harness made of webbing. The harness broke and he not only lost the fish, but the rod. line, and reel as well, for the fish took them with him. One of the brothers succeeded later in capturing a fish much to everyone’s satisfaction.

When I arrived at Santa Catalina Island I found that the kind secretary of the Tuna Club had engaged the 28-foot launch “Shorty” for me to fish in and told me that there were no marlin or tuna about, which was a great disappointment.

The boatman, “Shorty” by nickname, hailed originally from Harlem, and as we were both Gothamites we understood one another at once for we spoke the same language. The first mate was Pard, “Shorty’s” dog. Pard is a skilled fisherman and would always let us know when he saw a swordfish.

The Island of Santa Catalina is ever a joy to look at. Its bold beauty of outline and picturesque rocks, its sunny canons which appear from time to time as you coast along its shores, and the fog-banks that overhang the mountains in the early mornings always impress one greatly.

If you climb the hills and look down on the sea the picture is wonderful. You can see miles of coast line and the extraordinary colour of the sea can be observed, varying as it does from the palest and most impalpable of greens immediately under the shore to a deeper emerald beyond, and then as far as the eye can reach it is blue, the incomparable deep blue of the warm Pacific Ocean.

We started out at 8 A.M. the first day after my arrival at Avalon. I told “Shorty” to keep in shore and to zigzag along, one mile off shore then back to the edge of the kelp, for I wanted a marlin and they are supposed to be found in shore. The fog overhung the island and I could not see where we were going nor did I pay much attention for it was a joy to be in a boat on a smooth sea after four days of railroad travel.

We had been fishing about two hours when “Shorty” said: “Here is a broadbill and he is a buster; will you try him?” The local names for the swordfish are broadbill or flatbill to distinguish him from the marlin whose bill is round. I found that we were four miles off shore and that “Shorty” had been instructed to put me on to a big swordfish, and he did it with a vengeance.

I looked over my shoulder and saw the dorsal fin of a large fish moving slowly near by and his tail, which was partly above the surface, seemed to be at least six feet from the dorsal fin. He was moving through the water leaving no wake behind him such as a shark does, and making no use of his tail; this he is enabled to do owing to the great power of his pectoral fins.

The launch was slowed down. I had a flying-fish on the hook and let out 150 feet of line. The boatman now tried to maneuver the boat in such a manner that the bait would swing in front of and near the fish. This was difficult as the swordfish was turning the same way we were, seeming unwilling to cross our wake.

At last he saw the bait and as the fish sank the launch was stopped. He disappeared without a motion or the least flirt of the tail. The balance of these fish is perfection.

“Shorty” said: “He is now going down to give it the once over; turn everything loose and give him plenty of line.” The line was jarred as the fish struck the bait a hard blow and then it began to run out slowly. I gave him about two hundred feet and when the line became taut struck hard.

I had hooked my first swordfish!

He made a run of about two hundred yards and then sounded about six hundred feet, stayed down a few moments and allowed himself to be pumped up. He then came up to the surface and thrashed about in a circle, sounded again, was pumped up again. He did this several times. Within the first hour I had the double line, which was doubled back fifteen feet, on the reel three times and the wire leader was above the surface. We could see the fish plainly and “Shorty” said he would weigh over five hundred pounds, but fish always look big under those circumstances and I was too busy to estimate weights. One thing I had discovered: he was too heavy for me, for in some of his sudden plunges he had nearly pulled me overboard. For the first time in my life I wished I weighed two hundred instead of one hundred and thirty pounds.

Suddenly the fish made a dive under the boat. I turned everything loose and shoved the rod six feet into the sea. The fish came to the surface on the other side of the boat as “Shorty” started the launch ahead and the line cleared.

This woke Señor Espada up and he raised Cain for two hours. He tried every fish trick known and jumped clear of the surface so that I could not help getting a good look at him. He was a very big fish; his sword looked five feet long to me, but everything in me had been stretched by this time, even my eyesight and imagination.

It had been a cold foggy morning. I had on two sweaters. First one then the other had been peeled off. Then my collar and my hat had been thrown aside. “Shorty” remarked about this time that if I kept on I would be naked before the fish was taken.

I fought the fish for all I was worth for four hours and twenty minutes, then brought him to the boat on his side. I had most of the double line on the reel and four feet of the leader out of the water. I called to “Shorty” to put the gaff into him. Just then the fish gave a last struggle and went under the boat and the line fouled on the upper end of the shoe that protects the propeller. The fish still on his side was under the boat in plain view but beyond the reach of the gaff and held by the fouled line.

I slacked my line to see if the boatman could clear it with the gaff. The bag of the slack line drifted under the boat. “Shorty” caught it with the gaff and cut it with his knife, then cut the line on the rod side of the boat, knotted the two ends, and told me reel in. I reeled in twenty-five feet or so of loose line and found he had cut the fish loose for he bad knotted the wrong end and had thrown the fish end overboard.

I thought much but said nothing!

I put my rod down with relief mingled with disgust and looked over the side of the boat at the swordfish. He slowly revived a little, struggled, pulled the end of the line free and sank.

I had been very tired at the end of the first hour but had my second wind and was going strong at the finish.

I was a pretty stiff fisherman the following day. All my old hunting and polo breaks and strains were in strong evidence. If there had been a trout stream on the island I would have gone trout fishing. Trout were about my size that day.

Trying to make the fish take the bait and the moments that passed after the fish faded away beneath the surface and until he was hooked were moments of great excitement, but the rest of the time had been too hard work to call it unadulterated pleasure.

There were members of the Tuna Club at Avalon who had fished for forty, yes, fifty days and had not persuaded a fish to take the bait, and I had hooked one before I had been fishing two hours. They called that good luck but I did not feel that way at the moment, yet I revived quickly.

A few days later I hooked another large fish, pumped and hauled him for three hours, and broke my rod at the butt. The boatman spliced the rod while I held the tired fish with the tip. I then brought the fish alongside in twenty minutes more quite ready to gaff. The boatman had the leader in one hand and the gaff in the other when the leader caught between the brass cap of the exhaust, which was not screwed home, and the side. of the boat. The hook straightened out and the fish sank. The hook had been in the corner of his hard mouth.

Swordfish were very plentiful that summer for the first time. I counted and fished for nine one morning not five miles from Avalon. Some days they seem very shy and will not look at any bait. It is the custom to try a barracouta for bait if they refuse the flying fish, and if they do not take that an albacore may entice them. They have been known to take an albacore weighing twenty-four pounds.

After ten days’ fishing for broadbills I left for Clemente, to look for marlin, where I remained three days and on my return had five more days with the swordfish.

The sea was like glass most mornings so that the fish could be seen at a great distance.

In the last five days I tried about twenty-five broadbills but only hooked one. The others would either cut the bait off the hook or else pay no attention to it but swim off and come to the surface one hundred yards r more away, where we would follow and try again. We often wasted two hours after one fish in this manner. If the fish are not hungry this treatment seems to bore them for they will jump out clumsily four or five times.

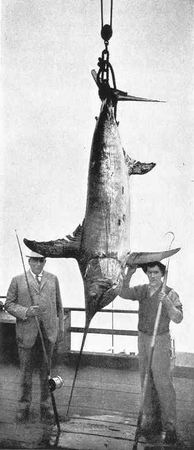

MR. J. S. DOUGLAS’ SWORDFISH

404 pounds

I played the third fish four hours and forty minutes, “Shorty” taking the rod for a short time to allow him to feel the weight of the fish. When the fish seemed to be leading nicely the hook pulled out. I am sure he was foul-hooked in his thin-skinned body for I could feel the hook slip from time to time. After the first hour he jumped at least ten feet into the air showing plainly his broad back, which looked as wide as the bottom of a canoe. He then ran out six hundred feet of line and fought on the surface. This amused the dog, Pard, greatly.

It is difficult to persuade a broadbill to bite and still more difficult to hook him, and if he is a big one, still more difficult to do anything with him after he is hooked.

He is a much more interesting fish to fight than the large tuna for he is a better general and no two fish seem to fight alike. There is a sameness about tuna fishing that does not exist in swordfishing.

It would be quite impossible to kill these fish without the modern reel with its heavy drag; thumb pressure alone could not do it, the fish are too strong.

This fishing was a lesson to me in what fishing tackle will stand. I did not think it possible that a split bamboo rod and a 24-thread line could stand such a strain.

The rod I broke had just come from the shop after having a new ferrule fitted on the tip. The workman must have damaged the outer skin of the bamboo for the rod broke gradually.

It was hard work but a great experience, for one learns something every day one fishes, no matter how many days or how many years one devotes to the sport.

Click

here to continue to the next chapter of

Some Fish and Some Fishing