|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

II

TARPON FISHING

IT does not seem to be generally known that tarpon frequent the rivers of Cuba, though they are to be found at all seasons of the year in a few of the rivers. I say a few of the rivers, for, having searched for them in about twenty, I have found them in only five—in the “Zara” on the north coast, in the Jatibonico, Rio Negro, and Damuji on the south coast, and in the Los Angeles River on the Isle of Pines. Most of the rivers in Cuba are fed from swamps, and their waters are dark and in a muddy condition, which does not seem to appeal to the tarpon. The rivers I speak of are fairly clear, and the Rio Negro is as clear as crystal. The fish trade up and down the rivers on the tide, and are very certain to leave for the open sea just before a northerly storm. You find them in schools of twenty or more fish of an average weight. The small fish seem to remain for several years in brackish water before going to sea. There are numbers weighing from three to five pounds, and beautiful little fish they are to look at and delightful to take on light tackle.

To fish in Cuba you must have a vessel adapted to the waters. She must have power as well as sail and must not draw more than four feet. The rivers are deep, except over the bars at the mouth, where they are very shoal. The tarpon do not seem to go above the tide into fresh water. The limit of the mangrove growth, which does not grow along fresh water, is the limit of the fish. The rivers are lined with mangrove trees and royal palms, and the current is never rapid, so that the waters are ideal for fishing. The fish will average about one hundred pounds, but now and then you will meet a school of giants.

I have cruised from Nuevitas Bay on the north coast around the western end, of the island to Cienfuegos on the south and have tried most of the rivers that looked promising for sport. I have always fished there in the month of February, and have never failed to find tarpon. In four winters, during a few days’ fishing each season, I have played almost two hundred tarpon. I say “played,” as I never kill a tarpon unless he is hooked in such a manner that he cannot be set free. I believe that it takes many years for them to grow to maturity, and it seems wicked to destroy such game fish. The natives in Cuba are glad to have them, as they eat them fresh and salted.

The fishing in Cuba in winter is charming, the climate being perfect, with no flies or insects of any kind; but the trip there and back for a small vessel is not easily to be forgotten. With a northerly wind—and it always seems to blow from that quarter— the Gulf Stream is the roughest bit of water that I have ever navigated, and the run across from Justias Key to Key West is a nightmare. There are other fish, such as snapper, jackfish, grouper, kingfish, Spanish mackerel, and barracouta, to be found off the coast and in the rivers, and I have seen bonefish for sale in the market. Sharks of many varieties and of the largest kind abound.

Winter fishing for tarpon is river fishing, and, in my opinion, is the most interesting and sportsmanlike manner of fishing for the grandest of sea-fish.

Some ten years ago I was cruising in the Indian River, Florida, in a house-boat, and found the St. Lucie River full of tarpon. The good people who live in the neighborhood of Sewall’s Point had cut the beach opposite where the St. Lucie empties into the Indian River, for the purpose of deepening the latter and providing a port that would help them to develop that part of Florida. It did not have quite the desired effect, for Gilbert’s Bar at the mouth of the inlet is not a pleasant harbor to make, and the Indian River now has less water at that point than it had before. By letting in the salt water, they changed the character of the lovely St. Lucie River; for the brackish water killed all the vines that hung in garlands from the trees. It also changed the character of the fish to be found there.

Mullet in great schools came into the river on the flood-tides, and were to be, found ten miles up the North Branch, and tarpon followed the mullet in large numbers. I saw more tarpon that winter, and larger ones, than I have seen in the ten years since. It was that winter that I acquired the taste for river fishing.

The tarpon that come to the rivers, bayous, and inlets of our coast in April and May in great numbers leave in the autumn, supposedly for the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream; but some fish remain in the deep rivers of the east coast of Florida all winter. They do not show on cold days; but if the water is sixty-eight degrees, or warmer, you can see them, and can fish for them with some hope of success.

It gives me more satisfaction to kill one tarpon in January than ten in the month of May, when they are plentiful. I troll from a rowboat with a live silver mullet hooked through the head. If the hook is properly placed and the mullet gently handled, it will live for hours. I have fished in this manner for several winters, killing a number of fish. The largest two were 187 pounds, caught on Jan. 26, and 165 pounds, on Feb. 23.

The moment the fish strikes and feels the hook, he jumps first to one side of the river and then to the other, for the rivers are not wide, and then comes straight toward your boat, fighting all the time. It is then that you generally lose him, for he will jump half out of the water beside the boat when your line is straight up and down. It must be a well-hooked fish that does not then shake the hook free.

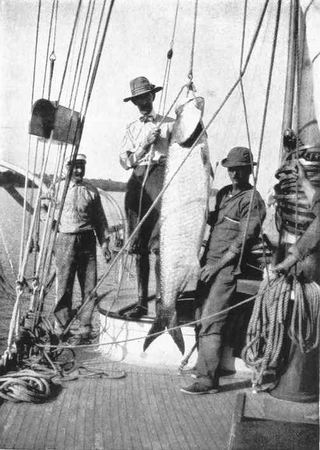

TARPON TAKEN IN THE RIO NEGRO, CUBA

Weight, 130 pounds

One winter I sailed from Key West for Cuban waters and cruised along the northern coast of Cuba, looking for tarpon. I found a lovely river, called the Zaraguanacan, a tiny river for such a long name, but full of tarpon of all sizes. In places it is very narrow, and its shores are thickly covered with mangroves. The water is deep, and the fish work up and down the river on the tide. While there I jumped fifty-two tarpon, and saved only nine. I was not sorry to lose any of the fish that I had played, for they are so game that it is always painful to gaff them. In this case it was most amusing to lose them, for the third jump would generally land them high up in the overhanging branches of the mangroves, through which they would crash into the deep waters below, leaving my tackle entangled in the bushes.

The result of river fishing does not mean a large bag. It is quick work, for you must not give the fish any slack, a difficult thing to avoid, as you have no tide in your favor, as in pass fishing, to keep your line taut. The gentle current of the Southern rivers is of little assistance, even if you are fortunate enough to jump your fish when trolling against it. The rivers are deep, and the waters are dyed by the cypress roots and fringed with white lilies. The banks are lined with cabbage-palms and deciduous trees, which in January are just budding, spring then beginning along these lovely rivers so little known to tourists in Florida.

I do most of my fishing with the assistance of a launch. With the advent of the automobile, a new way of seeing the world was discovered for the tourist, and years of keen pleasure offered to those who love travel. The coming of the motor-boat has done the same for fishing.

I remember being surprised some years ago at Captiva Pass by the complaints made about one fisherman, because, cruising about in a launch near where we were fishing, he frightened the fish with his propellers and so drove them out to sea. I did not believe it at the time, and I have since had many opportunities to prove that, on the contrary, the disturbance work up the fish and encourage them to take notice and strike. There is a pool in New River which motor-boats pass through a hundred times a day, and the tarpon remain there all the time if the water is not too sweet; in this case they go to sea, and return when the rain-water has run out. At Catalina, Calif., you almost always fish in launches. You can cover much more space, your bait trolls more steadily, and you have not the feeling that the man at the oars is rowing his heart out.

The best boat is a large rowboat with one and one-half horse-power gasolene-spark engine. The boat must be light, for your boatman must have his oars ready to assist you in playing your fish when it is hooked. You need but little power, for you should not travel faster than a man can row, and most one-cylinder engines do not slow down graciously.

I have fished in this manner for the last few years, believing the old way of trolling to be quite out of date. In a few seasons’ fishing I have taken tuna, tarpon, hundreds of kingfish, grouper, barracouta, muttonfish, cavalli, pompojacks, ladyfish, bonito, bluefish, and Spanish mackerel.

In tarpon-fishing I usually am towed in a rowboat, for the reason that my launch travels more slowly with the weight astern. The boatman casts off when I tell him to, and the launch goes on out of the way. I have done this with good success not only in rivers, but also in the open sea and along tide-rifts in the passes.

This method of fishing has, however, one great drawback: if you are trolling with a live mullet, it soon dies, and revolves like a pinwheel. Most cut baits will do the same, as spinners will also; and no number of swivels or “anti-kinkers” will prevent your line from being ruined in short order. This gave me much trouble for some time, but I heard of a new improved fishing-gear, or “skittering device,” patented by Albert W. Wilson of San Francisco, for striped-bass fishing, which is in general use on the Pacific coast for that purpose. This spoon I consider the most wonderful fishing invention of modern times. It “swims” erratically, swerves from side to side, and yet never revolves, so that your line does not kink in the least. In addition to this, it attracts all kinds of sea-fish. Tarpon, kingfish, grouper, and even sharks seem to take to it most kindly.

These spoons are made in different sizes and are very nicely balanced, as they must be, or they would trail along on the surface of the water. The steady movement of a motor-boat just suits them.

The curse of sea-fishing is the difficulty of getting fresh bait. I have been for days in Florida or off the Cuban coast with no bait to be had. But that time has gone by, thanks to the “Skittering Wilson,” and motor-boat fishing has been made possible.

Click

here to continue to the next chapter of

Some Fish and Some Fishing