| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XX

ALLIGATORS AND WILD TURKEYS Out in the wild country to the westward of the St. Lucie River the winds of dawn mass fluffy cumulous clouds along the horizon, and the morning sun tints these till it seems as if a vast golden fleece were piled there to tempt westward faring argonauts. Thither I journeyed for nearly a day, the slow trail ending in a land of enchantment fifteen miles beyond the nearest outpost of civilisation. Most of this trail led through the dry prairie where short, wire grass grows among widely scattered, slim pines, the slimness seeming to come rather from lack of nourishment than youth, for the soil here is but a thin and barren sand. Then the earth beneath us sank gently and the water rose till the good sorrel horse was splashing to his knees in water that was crystal clear and that deepened in spots till the hubs rolled n its surface. Schools of tiny fishes darted may as we splashed on, bream and garfish, bass and sea trout, spawned no doubt in some branch of the upper waters of the river and venturing onward in companionable explorations wherever a half-inch of water might let their agile bodies slip. We were on the border of "Little Cane Slough;" and we fared on amphibiously thus some miles farther, coming at last to the country of islands which was our destination. In the geology of things Florida was once sea bottom, having been pushed up by a fold in the earth's strata which made the Appalachian mountain range. The giant force which raised these mountains thousands of feet high was early spent when it came to this part of the country and barely succeeded in getting the State above high tide. Thus the waters subsiding slowly made no extensive erosion. Yet they did their work and Little Cane Slough was once a river of salt water flowing out of the surgent State. In its slow, broad passage, the flood took some surface with it, leaving a bare, sandy bottom in the main free from any hint of humus in which vegetation might grow. In other spots it left the surface mud in higher islands of unexampled fertility. Some of these islands are scarcely a hundred feet in diameter. Others measure a half mile or so, but all to-day are covered with a dense growth of vegetation from grass and shrubs to mighty trees of many varieties. Hence you have an enchanting mingling of shallow, clear ponds, grassy and sedgy meadows and wooded islands, a country which all wild creatures love. The place is marked on the map as a lake. There are years and times of year when it is that, then drought reaches deep and the only water you can find is in the alligator holes into which fish and alligators both crowd till these tenement districts are much congested. The sun which had started behind us in our westward race for the golden fleece of cumulous clouds outdistanced us and sank to victory among them, big and red with his running, but we camped on one of these thousand islands. You may venture into haunts of the alligator without fear. I doubt if there was ever a time when the largest of them would attack a man, certainly the few that are left wild have a wholesome fear of him and you must be stealthy of foot and quick of eye to even see one.

Twenty years ago fifteen

footers promenaded from one deep hole to another, and their broad

paths, worn through the thin surface of fertility, are left still, the

grass not yet having found sufficient foothold to obliterate them.

Rarely does one make trips like that to-day. They all stick too closely

to their holes, and so cleverly are these placed that a screen of

bushes or rushes conceals the saurian when he is up sunning himself,

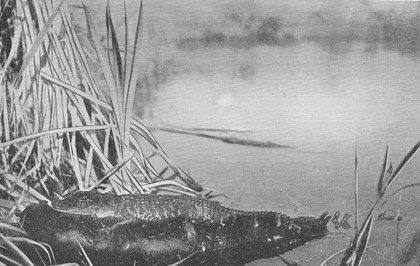

and he has but to plunge to find safety.  "My first glimpse came at one of these places" My first glimpse came at one of these places, a deep pool surrounded by a growth of flags. Close beside this was a bushy island, and in one corner of the island was a smaller pool not over a dozen feet in diameter. Between the two, halt screened by the bushes, lay Mister Alligator enjoying a mid-afternoon nap, but a nap in which he slept with one eyelid propped up. One gets so used to scaly monsters in the Florida woods, rough trunks of scrub palmettos that continually simulate saurian ugliness, that it took me a moment to see him, even when my companion pointed him out. Surely there could be nothing of life in that inert stub. But even as I looked there was a most prodigious scrambling of clawed feet, a swish of a tail so big and husky that it seemed to wag the alligator, and he was in with a plunge, not into the big pool as I expected, but with a dive into the little one beneath the bushes, an action that let me into one of the secrets of alligator housekeeping. A good part of that afternoon and pretty nearly all of the next day I spent, with my companion, who has been intimate with alligators for many years, in wading, often waist deep, in the sunny, clear, tepid water, from one alligator hole to another, and in that way I learned much of the real life of the beast. A grown alligator is a huge and formidable-looking reptile, but so great a fear has he of man that you have but to show yourself and say "Boo!" and he will make the water boil in his frantic endeavors to escape. You may go swimming in his private pool if you will and he will crowd down in the mud of its deepest hole to escape you. Only when cornered and continually prodded will he show fight. Then he may bite you with his big mouth or club you with his bigger tail, but it will be only that he may get an opportunity to get away. There is much interesting fiction about alligators that eat pickaninnies or even grown-ups, but I do not believe it has any foundation in fact.

I found several alligators'

nests, big heaps of thin chopped reeds, dried leaves and rubbish, in

which in midsummer the eggs are laid, white and with a tough, leathery

skin, about as big as a hen's eggs. Last year's eggshells still linger

about these nests. The heat and steam of the sub-tropical swamp hatches

the eggs without further trouble on the part of the mother. She,

however, stays not far away and if you wish to see her you have but to

catch one of these lithe, wriggly youngsters after they are hatched and

pinch the tail. The squeak of pain will usually bring a rush from the

big one, though even then the sight of a man is enough to send her back

again in a hurry. The young alligators are born on the banks of the

pool in which their mother lives, and they need to be agile else their

father will eat them. As for food, every alligator hole that I have

visited swarms with fish.  "The heat and steam of the sub-tropical swamp hatches the eggs without further trouble" Getting the sunlight just right on one of these alligator swimming pools I have seen, besides great store of small fishes swimming about the margin, hundreds of broad bream schooling in it, while bass and garfish two feet long lay in the deeper parts. So far as fish go the alligator need not go hungry. Often, too, he may get a duck or a heron, coming up with a snap from beneath the surface before the bird has a chance to rise from the water. I have seen a raccoon floundering and swimming in the shallows, his diet no doubt mainly fish, and he himself liable to capture by the alligator. But the inner domicile of the alligator is not in the big pool. It is in the lesser one, and from this he has an entrance to a cave he has dug in the earth far beneath the bushes. Often you may prod in this cave with a fifteen-foot pole and not touch the reptile, so deep does it go. This is his refuge, his hiding-place. In time of danger or in cool weather he may lie at the bottom of it for days at a time. When he comes out again it is most circumspectly. He floats craftily just to the surface and lets his nostrils and his eyes, which are placed just right for this feat, come above the surface, while all the rest of him is submerged. If you are familiar with alligators you may recognize these at a considerable distance; if not you will surely think them floating bits of bark or rubbish. Yet in time of low water this very refuge of the animal is his undoing. The alligator hunter comes to the pool armed with a long rod with which he jabs and prods till he finally drives his quarry to the surface to his death. Sometimes this iron has a hook on the end with which the reluctant beast is hauled out. Such hunting. means close quarters and is not without excitement. In times not long past, this sort of pot-hunting was much followed. Now the hunter most often "jacks" for his game, paddling at night with a bullseye lantern attached to the front of his hat like a miner's lamp. The beast in stupid curiosity watches the gleam of this light and the hunter sees it reflected from his eyes. Curiously enough, you may see this reflected glare well only when yourself wearing the lantern. You may stand beside the man wearing it and never get the reflection, however he turns his head. The reason for this, no doubt, is that the eyes of the watching beast are focused on the light alone and hence send its rays directly back. Now and then the jack hunter grunts mysteriously from deep within himself. This ventriloquism is supposed to be an imitation of the call of a young alligator and is used to lure the old one. But not for fish and alligators merely is this bewitching country of islands set in the middle of Little Cane Slough. Here are innumerable flocks of the Florida little blue heron, ranging in numbers from three to fifty, wading and feeding mornings and evenings, resting at midday on tops of dead stubs, where the young birds, still in white plumage, are most conspicuous objects. The bald eagles that had ten bushels or so of nest in a big pine just east of our camp must find these birds easy game. Nor are the white youngsters, seemingly, unaware of this. Their blue elders often sit hunched up, asleep, but these hold the head erect and crane the neck this way and that, as if perpetually wondering whence trouble might come. Among these birds I saw for the first time the change of color from youth to maturity, from white to blue, going on. There were birds in the flocks that had blue backs and wing coverts while still white underneath. All about among these islands are well beaten trails of other creatures than alligators. The range cattle make some of them, but not all. In some you may see the duplex-pointed hoof-marks of deer. Some are scratched out by the hurrying claws of raccoons. In many, along the grassy edges I found the wide, dignified print of that king of wild birds, the wild turkey. Long and stealthily I prowled these trails hoping to come upon this majestic bird when feeding and thus see him at his work, but in this I was unsuccessful. The turkey feeds mainly in early forenoon and late afternoon, not leaving his perch as a rule till the sun is above the horizon, lurking among the bushes on high ground during the heat of the day, filling his crop again before sundown and flying heavily to his roost before dark. Just now his food is mainly succulent new grass with which he fills his crop until it will hold no more, fairly swelling him up in front like a pouter pigeon. There were a gobbler and two or three hens near-by --how near we were not to suspect until later; but we saw only the trail of these, not a feather of them did we glimpse, follow their tracks as we might. It was late in the afternoon and we were a mile and a half from camp when we heard the first turkey voice. It was that of a lone gobbler and, just by chance, I stopped knee-deep in the grassy lagoon on the margin of an island which held his favorite roost, a limb of a big pine standing among deciduous trees. To this, from the other side he came. No doubt he had been picking grass on the other margin of the lagoon in which we stood, now he was headed for home and calling.

At this time of year there

are great battles between gobblers for possession of hens. This gobbler

seems to have been a defeated and compulsory bachelor, yet he gobbled

away as if a whole barnyard was at his back, lifting his twenty-five

pounds of live weight with rapid beats of his short, strong wings from

the ground to lower limbs, thence higher and finally to his roost.

Never yet, I believe, grew a more magnificent gobbler than this one,

scorned of the fair se though he was. The level sun shone upon his

bronzed feathers till the radiance of their beauty fairly dazzled,

seeming to flash from him in molten rays as if from burnished copper.

He looked this way and that for those missing hens that surely ought to

be lured into following such radiance. He gobbled to right and he

gobbled to left in mingled defiance and entreaty, but there was no

reply. Then he strutted and displayed all his magnificence. He spread

the wide fan of his copper-red tail, drooped his wings fill they hung

below the limb and puffed out all his feathers, silhouetted against the

pale rose of the sunset. Then he said "Pouf!" once or twice in a half

hissing, sudden grunt that sounded as if it came from the bunghole of

an empty barrel. It had that sort of contemptuous hollow ring to it.

This he varied with gobbling for some time If afterward he put his head

beneath his wing and forgot his loneliness in slumber I cannot say, for

the south Florida sun whirled suddenly beneath the horizon and took his

roses and gold with him. The night was upon us and only the thinnest of

new moons lighted our way in the long splash back to camp. |