| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to

return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to

return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XVIII

IN GRAPEFRUIT GROVES The Spaniards brought the grapefruit to Florida, and left it behind them. Here it has been ever since, until the last ten or fifteen years neglected and despised, but taking care of itself with cheerful virility. It grew wild, or people planted a few trees about the house for its rapid growth of grateful shade and the picturesque decoration which its huge globes of yellow fruit furnished. These few people considered edible. Now we all know better and the North calls for grapefruit with a demand that this year is only, partly satisfied with four million of boxes.

Floridians eat the once

despised fruit with avidity now and a thrifty grapefruit grove is

already recognized as a profitable investment. I say a thrifty grove,

for all groves are not thrifty. The tree is lavish to its friends and

in congenial surroundings will produce fruit almost beyond belief. I

have seen a single limb not larger than my wrist weighed to the ground

with ninety-five great yellow globes by actual count. I have seen a

whole orchard that had been tended for years with assiduous care calmly

dying down from the top and sinking back into the earth from whence it

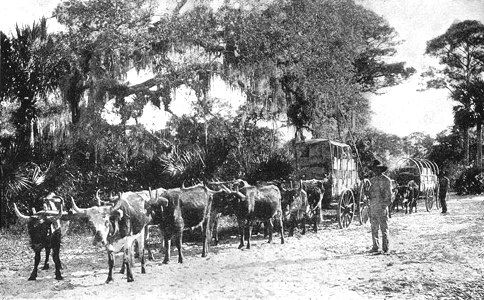

sprang.  "The tree is lavish to its friends and will produce fruit almost beyond belief" More than anything else the grapefruit must have the right subsoil under it. If you plant your trees where they may be well drained and where the soil beneath their tap-roots is a good clay, overlaid of course with the all-pervading Florida sand, they will love you for it. Care and fertilizer will do the rest, though even then it must be the right kind of care and of fertilizer. If you plant your trees where there is a " hard-pan bottom " neither love, money nor religion will bring them to good bearing. Why "hard-pan" which seems to be a dense stratum of black sulphuret of iron should be under the surface of one man's ten-acre lot, while under that of his next-door neighbor lies the beloved red clay, it is difficult to explain. Florida reminds me always of Cape Cod. It seems to be built out of the chips and dust of the making of the near-by continent, dumped irrelevantly. There is no telling why one acre is a desert that one would plough as uselessly as Ulysses ploughed the seashore and the next acre is fat with fertility, but it is so. Hence people plant grapefruit groves not where they will, but where they may, and you discover them in the most delightful out-of-the-way places. Paddling up river one day, ten miles from any habitation, along a stretch of profuse tropical forest, I heard the cluck of axle-boxes and a voice said "whoa!" Landing I found that the wilderness was but a sham, a thin curtain of verdure, and behind it was a stretch of fertile land covered by grapefruit trees in orderly procession, twenty-four feet apart each way, twelve hundred of them. This man must cart his fruit through ten miles of sandy barrens to the train. He might have set his trees along the railroad so far as cost of land was concerned, but they would not have grown there. Once a week there comes into Fort Pierce a team of eight runt oxen, bred of Florida range cattle stock, drawing a creaking wain laden down with orange and grapefruit boxes. Thirty miles across the barrens these have come, from groves out at Fort Drum, and they will take a load of groceries and provisions back. It takes six days to make the round trip and you may hear the team long before you see it. The man who drives these oxen carries a whipstock as tall as himself with a lash twice its length, long enough to reach the leading off ox from a position on the nigh side of the cart. On the end of this lash is a snapper which gives off a noise like that of a pistol. Hence the Florida woodsman is called a "cracker," a name which has come to be applied indiscriminately to all natives, whether drivers of oxen or not. Thus do we carelessly corrupt language. The cracker is the man who cracks his whip. Wherever the woodsman drives oxen you will hear it.

You find these pretty

groves thus scattered in the most picturesque spots and just to wander

in them is a delight. The fruit itself I suspect to be an evolution

from the shaddock, which is a huge, coarse thing growing on what looks

like an orange tree. Just as sometimes out of a rough-natured human

family is born some youngster of finer fiber who is an artist or poet

instead of clodhopper and we can none of us tell why or how, so no

doubt the grapefruit was born from some worthy shaddock tree and

astonished and perhaps dismayed its parents. All are great globes of

pale gold and surprise one with their size and profusion. How does this

close-fibered, toughwooded tree find in sun and soil the material to

produce such fruit? Here is e ten years old that holds by actual

measurement twenty boxes, almost a ton, of fruit on a tree that is

about fifteen feet high and six inches in diameter at the butt. It is

as if a thumbling pear tree in a Northern garden should suddenly take

to producing pumpkins and bring forth twelve hundred of them.  "Thirty miles across the barrens these have come, from groves out at Fort Drum" On the Indian River it is the custom to let the fruit hang until mid-March when the blossoms appear with it, making a grove a place of singular beauty. Out of the dense, deep green foliage spring a hundred yellow glows, while all the outside of the tree is stippled with a frippery of white, a dense green heaven set with golden suns in crowded constellations and all one milky way of starry bloom. The scent of these blooms, which is the scent of orange blossoms, overpowers all other odors and carries miles on the brisk March winds. There are other creatures that love the groves as well as I do. The mocking bird loves to pour his full-throated song from the tip of a blooming spray, and when the fervid sun of late March pours the whole world full of a resplendent hear which seems to lose its fierceness in these golden suns of fruit, caught there, concentrated, and built into a living fiber of delectability, he builds his nest in the crotch of some favorite tree. Twigs and weed stalks roughly placed make its foundation and outer defenses, the hollow being lined with silky or cottony fiber from wayside weeds. There are so many pappus-bearing plants whose seeds float freely that he may well have his choice, though if I were he I should save labor by taking the thistledown from the ditch sides. Here grow huge fellows whose heads of bloom, as big as my fist, set among innumerable keen spines can hardly wait to pass through the purple stage before they turn yellowish and then white with thistledown. For what else should these bloom it not for the lining of birds' nests? The mocker reminds me so much of the catbird that I had thought to find their eggs similar, but they are not. The catbird's egg is a rich greenish blue without a freckle; the mocking bird's is a paler, and blotched about the big end with cinnamon brown. When it comes to aesthetic standards I suppose the catbird's egg is the more beautiful, but any boy will agree with me that the mocker's egg with its wondrous blotching is the prettier. The blotching on birds' eggs is always a wonder and a delight. I remember the awed ecstasy with which as a small boy I looked upon the eggs of a sharp-shinned hawk, after having perilously climbed a big pine in a lonely part of the forest to view them. They were queer worlds most wondrously mapped with this same cinnamon brown. In a pelican rookery not long ago I was greatly disappointed that the huge eggs were merely a very pale, creamy or bluish white with a chalky shell. The eggs of such masterpieces of bird life ought to be equally picturesque. With the mocker in the groves is the Southern butcher bird. Just as at first glimpse I am apt to mistake one bird for the other, so when I find a mocking bird's nest I am not sure but it is a butcher bird's till I have looked it over a bit. The butcher bird's eggs are a little less blue of ground color and have some smaller lavender spots mingled with the cinnamon brown. The nests are lined more often with grasses than with seed pappus. Outwardly they look the same and seem to be built in similar places. The butcher bird is as friendly with man as is the mocker. A neighbor of mine has an arching trellis of cherokee roses over the walk from his back door to his packing house, and in the thorns of this a butcher bird has a nest, though the place is a thoroughfare and the nest almost within reach of one's hand. The bird has a slender little attempt at a song at this time of year which I do not find altogether unmusical. Some naturalist or other has claimed that the Southern butcher bird squeaks like the weather-vane on which he likes to sit. I would be glad if all weather-vanes which squeak did it as musically as this loggerhead shrike in nesting time. It is a thin but pleasant little shrill whistle, which does not, however, go beyond a few notes. Then the bird stops as if overcome with shyness, which he might well be, singing in a mocking bird country. There is another bird of the groves which I love well, much to the indignation of the owners, who pursue him with shot-guns. The Indian River fruit growers are hospitable to a fault. They will load you down with fruit as many times as you come to their groves and beg you to come again and get some more. But that is only if you are a featherless biped. The little red-bellied woodpecker who comes to the grove for a snack comes at the peril of his life. Little does he care for that, this debonair juice-lifter. He comes with a flip and a jerk from the forests over yonder, thirsty, no doubt. He lights on the biggest and ripest grapefruit that he can find and sinks that trained bill to the hilt in it almost with one motion. Within is a half-pint or so of the most delectable liquid ever invented. The bird himself is not bigger than a half-pint, the bulk of an English sparrow and a half, say, and how he can absorb all the liquid refreshment in a grapefruit is more than I know, but when he is done with it there is little left but the skin. The number of drinks that a half dozen of these handsome little birds will take in a day is surprising. It is no wonder the grower rises in his wrath and comes forthwith a shot gun. But it is of little use. The living wake the dead with copious potations of the same good liquor, and the woods are full of mourners. I watched one of these raiders drink his fill the other day and then go forth to a rather surprising adventure. After his drink he flew to the border of the grove, there to sit for a while with fluffed up feathers, in that dreamy satisfaction that comes to all of us when full. It lasted but a few moments, though, then he was ready for further adventures. On the border of the grove stood a fifty-foot tall stub of a dead pine, its sapwood shaking loose from the sound core of heartwood, but still enveloping it. In this rotting sapwood are grubs innumerable for the delectation of red-bellied woodpeckers who have drunk deep of grapefruit wine, and to this stub my bibulous friend flew in wavering flight, and with little croaks of contentment began to zigzag jerkily up and round it, now and then poking lazily into cracks with his bill and pulling out a mouthful. Thus he went on to within a few feet of the top. There he got excited, rushed about as if he saw things. He gave little chirps of alarm, put his bill rapidly into a crevice and drew it as rapidly out again, ran round the stub top and dived at another crevice, then came back, and with a frantic dig and scramble pulled out a six-inch snake, which he threw over his left shoulder, whirling and wriggling to the ground. It was a sure-enough snake, though of what variety I cannot say. I saw him, and my own potations had not been deep or of the kind which produces visions. I dare say he was a grub-eater himself and had worked his way up through the interstices of the rotten sapwood without realizing to what heights he had risen. The woodpecker was as surprised as I was and dashed nervously about for some time. I hope it may serve as a warning, but people who have the grapefruit habit are apt to be slaves for life. Often tearing through the grove goes Papilio ajax. Why this vast haste in such a place which invites us to linger and dream I do not know. He looks like a green gleam, flying backwards, a bilious glimpse of twinkling sea waves. The seeming backward motion is effective in saving the life of more than one specimen, for it makes the creature a most difficult one to net. I dare say the butcher birds and flycatchers have the same trouble and it is a wise provision on the part of nature for the continuation of the ajax line. He often vanishes against the green of the grove as if the working of a sudden charm had conferred invisibility on the flier. This trait of flying into a background and pulling the background in after it is common to many butterflies, who thus prolong life when insect-eating creatures are about. I had thought that Papilio cresphontes had none of this power till one vanished before my very nose, seeming to become one with a big yellow grapefruit, the grapefruit being the one. If I had been a cresphontes-hunting dragonfly I should have given it up. By and by I saw what had happened. Cresphontes had lighted on the yellow ball and folded his wings. All his under side, wings, body and legs, was clothed in a pale yellow fuzz that was like an invisible cloak when laid against the smooth cheek of the fruit. Here was the butterfly's refuge. No wonder this butterfly haunts the grove. He is one of the largest of the Papilio tribe, a wonderful black and yellow creature, the veritable presiding fairy of the grapefruit groves.

The fruit will soon be

picked and the golden suns will disappear from the deep green heaven.

The white stardust of the milky way of blooms will follow and the

groves would be lonesome and colorless if it were not for these great

black and yellow butterflies which will flit about them in increasing

numbers all summer long. I like to think of them as in their care,

waiting my return in the time of full fruit. |