|

Click Here to return to Boston Illustrated Content Page Click Here to return to Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Click Here to return to Boston Illustrated Content Page Click Here to return to Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

III. THE WEST END.

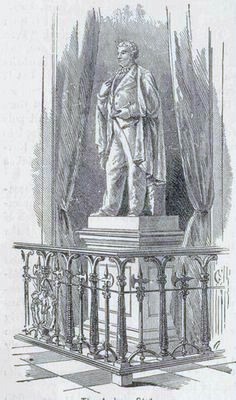

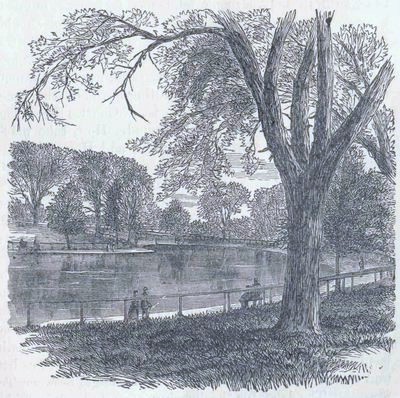

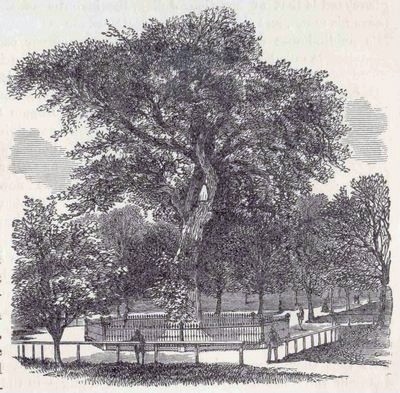

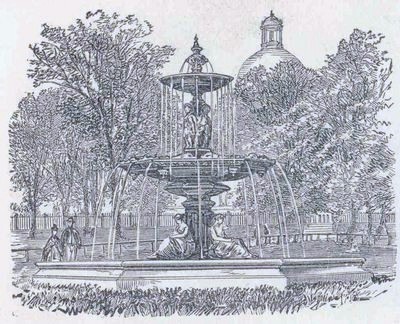

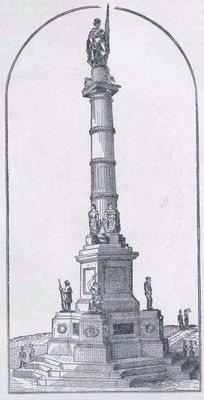

THE West End, like the North End, is difficult to define. We have already included in the latter division a part of what is usually termed the West End, and we must now, for convenience’ sake, embrace within the limits of the West End a part of the South End. Our division includes all that part of the city south and west of Cambridge, Court, and Tremont Streets, to the line of the Boston and Albany Railroad, following the line of that railroad to Brookline. These boundaries take in the whole of Beacon Hill, the Common and Public Garden, and most of the Back Bay new land, which is sometimes called the “New West End.” It has already been said that Beacon Hill, the highest in Boston, has been shorn of its original proportions. The three peaks of the original “Trea Mount” were where Pemberton Square and Louisburg Square now are, and the site of the old Reservoir. The hill was cut down in the early years of the present century, and Mount Vernon Street was laid out at that time; but it was not until 1835 that the hill where Pemberton Square now is was removed, and that Square laid out. Beacon Hill obtained its name from the fact that, for almost a century and a half from the settlement of the town, a tall pole stood upon its summit, surmounted by a skillet filled with tar, to be fired in case it was desired to give an alarm to the surrounding towns. After the Revolution a monument took its place, which stood until 1811, and was then taken don to make room for improvements. The highest point of the hill in its present shape is occupied by the Massachusetts State House, an illustration of which is given on page 30. So prominent is its position that it is impossible to make a comprehensive sketch of the city that does not exhibit its glistening dome as the central point of the background. The land on which the State House stands was formerly Governor Hancock’s cow-pasture, and was bought of his heirs by the town and given to the State. The corner-stone was laid by the Freemasons, Paul Revere grand master, in 1795, Governor Samuel Adams being present and making an address on the occasion. It was first occupied by the Legislature in January, 1798. In 1853—56 it was enlarged at the rear by an extension northerly to Mount Vernon Street, an improvement which cost considerably more than the entire first cost of the building. In 1866 and 1867 it was very extensively remodelled inside, and in 1874 was again repaired, and the dome was gilded. The extensive additions which are making to the State House occupy the site of the Reservoir on the northern slope of Beacon Hill. There are a great many points of interest about the State House. The statues of Webster and Mann, on either side of the approach to the building will attract notice, if not always admiration. Within the Doric Hall, or rotunda, is the fine statue of Washington, by Chantrey; here are arranged in an attractive manner, behind glass protectors, the battle-flags borne by Massachusetts soldiers in the war against Rebellion; here are copies of the tombstones of the Washington family in Brington Parish, England, presented to Senator Sumner by an English nobleman, and by the former to the State; here is the admirable statue of Governor Andrew; here are the busts of the patriot hero Samuel Adams, of the martyred President Lincoln, of Senator Sumner, and of Vice-President Wilson; near by are the tablets taken from the monument just mentioned which was erected on Beacon Hill after the Revolution to commemorate that contest. Ascending into the Hall of Representatives, we find suspended from the ceiling the ancient codfish, emblem of the direction taken by Massachusetts industry in the early times. In the Senate Chamber there are also relics of the olden time, and portraits of distinguished men. From the cupola, which is always open when the General Court is not in session, is to be obtained one of the finest views of Boston and the neighboring country. A register of the visitors to the cupola is kept in a book prepared for the purpose. During the season, which lasts from the 1st of June until Christmas, nearly fifty thousand persons ascend the long flights of stairs to obtain this view of Boston and its suburbs, an average of three hundred a day. The statue of Governor Andrew in Done Hall is one of the most excellent of our portrait statues. It represents the great war governor as he appeared before care had ploughed its lines in his face. This statue was first unveiled to public view when it was presented to the State on the 14th of February, 1871. It was paid for out of the surplus remaining of the fund raised in 1865 for the erection of a statue to the late Edward Everett. The portrait of Everett now in Faneuil Hall was also procured and paid for, and a considerable sum was voted in aid of the equestrian statue of Washington, which stands in the Public Garden, from the surplus of this fund. The sculptor was Thomas Ball, a native of Charlestown, but long resident in Florence, Italy. In 1883 he had a studio in Boston. The marble is of beautiful texture and whiteness, and the statue is approved both for its admirable likeness of the eminent original and for its artistic merits.  The Andrew Statue. There is nothing in Boston of which Bostonians are more truly proud than of the Common. Other cities have larger and more pretentious public grounds none of them can boast a park of greater natural beauty, or better suited to the purposes to which it is put. Everything is of the plainest and homeliest character, the velvety greensward and the over-arching foliage being the sufficient ornaments of the place. There is, however, the Frog Pond, with its fountain, where the boys may sail their miniature ships at their own sweet will; and there was until 1882 the deer park, a delightful and popular resort for the youngest of the visitors to this noble public space. Here, also, on one of the little hills near the Frog Pond, is the elaborate soldiers’ and sailors’ monument. All the malls and paths are shaded by fine old trees, which formerly had their names conspicuously labelled upon them, giving an admirable opportunity for the study of what we may call grand botany. The history of the Common is most interesting. After the territory of Boston was purchased from Mr. Blaxton by the corporation of colonists who settled it, the land was divided among the several inhabitants by the officers of the town. A part of it was set off as a training-field and as common ground, subject originally to further division in case such a course should be thought advisable. In 1640 a vote was passed by the town, in consequence of a movement on the part of certain citizens that was discovered and thwarted none too soon, that, with the exception of “3 or 4 lotts to make vp ye streete from bro Robte Walkers toy’ Round Marsh,” no more land should be granted out of the Common. It is solely by the power of this vote and the jealousy of the citizens sustaining it that the Common was kept sacred to the uses of the people as a whole from 1640 until the adoption of the city charter, when, by the desire of the citizens, and by the consent of the Legislature, the right to alienate any portion of the Common was expressly withheld from the city government.  The Frog Pond. The earliest use to which the Common was put was that of a pasture and a training-field on muster days. The occupation of the Common as a grazing-field continued until the year 1830, but it was by no means wholly given up to that use. As early as 1675 an English traveller, Mr. John Josselyn, published in London an “Account of Two Voyages,” in which occurs the following notice of Boston Common: “On the south there is a small but pleasant Common, where the Gallants a little before sunset walk with their Marmalet-Madams, as we do in Moorfields, etc., till the nine a clock Bell rings them home to their respective habitations, when presently the Constables walk their rounds to see good orders kept, and to take up loose people.” Previous and long subsequent to this the Common was also the usual place for executions. Four persons at least were hanged for witchcraft between 1656 and 1660. Murderers, pirates, deserters, and others were put to death under the forms of law upon the Common, until, in 1812, a memorial, signed by a great number of citizens, induced the selectmen to order that no part of the Common should be granted for such a purpose. Those who have studied the history of Boston most closely are of opinion that on more than one occasion a branch of the great Elm, which stood until 1876, was used as the gallows. And near that famous tree was the scene of a lamentable duel, in 1728, resulting in the death of one of the principals, B. Woodbridge. The level ground east of Charles Street has been used from the very earliest times as a parade-ground. Here take place the annual parade and drum-head election of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, the oldest military organization in the country, and here the Governor delivers to the newly elected officers their commissions for the year. The original boundary of the Common was quite different from the present. On the west it was bounded by the low lands and flats of the Back Bay; on the north by Beacon Street to Tremont Street; thence by an irregular line to West Street; and thence to the corner of Boylston and Carver Streets, and upon that line to the water. Upon that part bounded by Park, Beacon, and Tremont Streets were once situated the granary, the almshouse, the workhouse, and the bridewell. In 1733 a way was established across the Common where Park Street (which was formerly called Centry Street) now is. Since the establishment of that street, the land occupied by the institutions above named has been sold for private purposes. Compensation has been made to some extent by the addition of the land in the angle between Tremont and Boylston Streets. The land for the burying-ground was bought by the town in 1754 and that part where the deer park was situated in 1787. On the west a considerable piece was cut off when Charles Street was laid out, in 1803, but here also there was rather a gain than a loss, since the piece so amputated was enlarged by filling flats, and added to the public grounds. The area of the Common is now forty-eight and a quarter acres. The site of the Old Elm is now partly occupied by two young descendant trees. The Old Elm was certainly the oldest known tree in New England. On the great branch broken off by the gale of 1860 could be easily counted nearly two hundred rings, carrying the age of that branch back to 1670. It is surmised that the supposed witch, Ann Hibbens, was hanged upon it in 1656, and if so, it could have hardly been less than twenty-six years old, which would make the Old Elm as old as the town of Boston. A gale in 1832 caused the tree much injury, and the limbs were restored to their former places after which they were secured by iron bands and bars. The great gale of June, 1860, tore off the largest limb and otherwise mutilated it, and again it was restored as far as was possible, and the cavity filled up and covered. in September, 1869, a high wind that blew down the spires of many churches in Boston and vicinity made havoc with the remaining limbs; and in 1876 what was left of the venerable tree was blown down. The Frog Pond was, probably, in the early days of Boston, just what its name indicates, — a low, marshy spot, filled with stagnant water, and the abode of the tuneful batrachian. The enterprise of the early inhabitants is credited with having transformed it into a real artificial pond. This pond was the scene of the formal introduction of the water of Cochituate Lake into Boston, on the 25th of October, 1848. The water was let on through the gate of the fountain, amid the shouts of the people, the roar of cannon, the hiss of rockets, and the ringing of bells.  The Old Elm, Boston Common. The burying-ground on Boylston Street, formerly known as the South, and later as the Central Burying-ground, is the least interesting of the old cemeteries of Boston. It was opened in 1756, but the oldest stone, with the exception of one which was removed from some other ground, or which perpetuates a manifest error, is dated 1761. The best-known name upon any stone in the graveyard is that of Monsieur Julien, the inventor of the famous soup that bears his name, and the most noted restaurateur of Boston in the last century. His public-house was for many years on the corner of Milk and Congress Streets. He died in 1805, but his famous soup still flourishes. It is probable that this graveyard was early used for the interments of Roman Catholics, and strangers dying in the town, whose homes were in distant lands as well as in other parts of the new country. It is a tradition that several of the British soldiers who died from the wounds received at Bunker Hill or from disease, in the barracks, during the siege, were buried here. But there is nothing to indicate this, and the statement is questioned. Drake, however, says that they were buried in a common trench, and that years afterward many of the remains were exhumed when changes in the northwest corner of the yard were made. This burying-ground formerly extended to Boylston Street, and it was contracted to its present dimensions when the Boylston Street mall was laid out in 1839. The portion of the Common occupied by it and the now abandoned deer-park to the east of it, was not a part of the Common as originally bounded, but was purchased for it in after years. One of the most conspicuous objects on the Common, standing in the lawn near the Park Street wall, is the Brewer fountain, the gift to the city of the late Gardner Brewer, Esq., which began to play for the first time on June 3, 1868. It is a copy, in bronze, of a fountain designed by the French artist Liénard, executed for the Paris World’s Fair of 1855, where it was awarded a gold medal. The great figures at the base represent Neptune and Amphitrite, Acis and Galatea. The fountain was cast in Paris, and was procured, brought to this country, and set up at the sole expense of the public-spirited donor. Copies in iron have been made for the cities of Lyons and Bordeaux; and an exact copy, in bronze, of the fountain on the Common was made for Said Pacha, the late Viceroy of Egypt.  The Brewer Fountain. A monument commemorative of the Boston Massacre was erected on the green facing Tremont Street in 1888. The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, on the hill near the Frog Pond, was designed by Martin Milmore, and dedicated on September 17th, 1877, when the entire militia force of the State paraded in Boston, and was reviewed by the President of the United States. The platform is thirty-eight feet square, and rests on a mass of subterranean masonry sixteen feet deep. Four projecting pedestals sustain four bronze statues, each eight feet high, representing Peace, a female figure bearing an olive-branch and looking to the South; the Sailor, a picturesque mariner carrying a drawn cutlass, and looking seaward; History, a graceful female figure, in Greek costume, holding a tablet and stylus, and looking upward; and the Soldier, perhaps the best statue on the monument, representing a Federal infantryman standing at ease, and bearing the face of a citizen-soldier rather than that of a professional warrior. Between these pedestals are four large bronze reliefs. In the front is “The Departure for the War,” with a regiment marching by the State-House steps, the mounted officers, from left to right, being Colonels Lowell and Shaw, both of whom were killed, Colonel Cass, General B. F. Butler, and Quartermaster-Gen. Reed. On the steps are the Revs. Turner Sargent, A. H. Vinton, Phillips Brooks and Arch-bishop Williams; Governor Andrew, shorter than the others; Wendell Phillips, Mr. Whitmore, the poet Longfellow, and others. The second bas-relief shows the work of the Sanitary Commission, the left-hand group being on duty in the field, with the Rev. E. E. Hale at its head; and in the other group the seven gentlemen are E. R. Mudge, A. H. Rice, James Russell Lowell, Rev. Dr. Gannett, George Ticknor, W. W. Clapp, and Marshall P. Wilder (from left to right). “The Return from the War” is the most elaborate of the reliefs, and contains forty figures. The veterans are marching by the State House, and are surrendering their flags to Governor Andrew, while joyful wives and children break the ranks of the regiment. The mounted officers arc Generals Bartlett, Underwood, Banks, and Devens (from left to right); the civilians are Dr. Reynolds, Governor Andrew, Senator Wilson, Governor Claflin, Mayor Shurtleff, Judge Putnam, Charles Sumner, C. W. Slack, James Redpath, and J. B. Smith. The fourth relief represents the departure of the sailors from home (on the left) and an engagement between a Federal man-of-war and monitor and a massive Confederate fortress.  Army and Navy Monument, Boston Common. The main shaft of the monument, a Roman-Doric column of white granite, rises from the pedestal between the statues; and at its base are four allegorical figures, in high relief and eight feet high, representing the North, South, East, and West. On top of the capital are four marble eagles. The most prominent feature of the monument is the statue of America, eleven feet high, symbolized by a female figure, clad in classic costume, and crowned with thirteen stars. In one hand she holds the American flag, in the other a drawn sword and wreaths of laurel; and she faces the south. The bronzes were cast at Chicopee, Mass., and at Philadelphia; and the stone is white granite from Hallowell. The monument bears the following inscription, written by the President of Harvard College : —

TO THE MEN OF BOSTON

WHO DIED FOR THEIR COUNTRY ON LAND AND SEA IN THE WAR WHICH KEPT THE UNION WHOLE DESTROYED SLAVERY AND MAINTAINED THE CONSTITUTION THE GRATEFUL CITY HAS BUILT THIS MONUMENT THAT THEIR EXAMPLE MAY SPEAK TO COMING GENERATIONS. |