|

1999-2003

(Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to

Content Page

|

(HOME)

|

|

I. A GLANCE AT ITS HISTORY, Final Section.

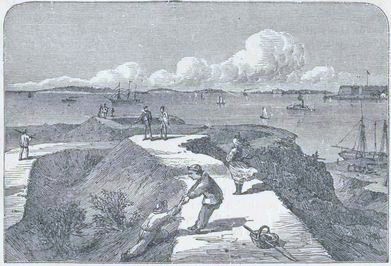

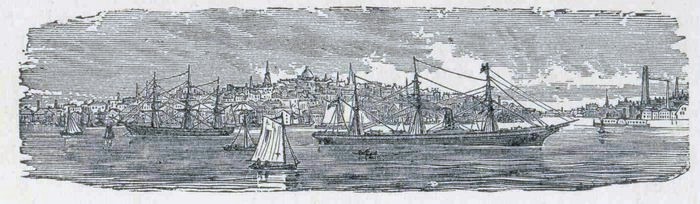

The history of the thirty years preceding the Revolution is full of incidents showing the independent spirit of the inhabitants of Boston, their determination not to submit to the unwarrantable interference of the British government in their affairs and particularly to the unjust taxation imposed upon the Colonies, and their willingness to incur any risks rather than yield to oppression. As early as 1747 there was riot in Boston, caused by the aggression of British naval officers. Commodore Knowles, being short of men, had impressed salon in the streets of Boston. The people made reprisals by seizing some British officers, and holding them as hostages for the return of their fellow-citizens. The excitement was great, but the affair terminated by the release of the impressed men and the naval officers, the first victory registered to the account of the resisting colonists. Twenty years later the town was greatly agitated over the Stamp Act; and hardly had the excitement died away when, on March 5, 1770, the famous Boston Massacre took place. The story is familiar to every schoolboy. The affair originated without any special grievance on either side, but the whole population took the part of the mob against the soldiers, showing what a deep-seated feeling of hostility existed even then. The scene of this massacre was the head of King, now State Street, east side of the Old State House. This building was erected in 1748, on the site occupied by the Town House destroyed by fire the year previous, and is one of the few historic structures in the city now remaining. Here for a while the courts of the colony were held; it has been the meeting place of the colonial general court and after the Revolution of that of the Commonwealth for a time it was occupied in part as a barrack for British soldiers; in one of the upper halls sat the Provincial Council, and it was here that Samuel Adams,after the massacre, made his memorable and successful demand for the removal of the British regiments from the town. Here the first post office in Boston was established; and the first merchants’ exchange; and after the town became a city, it was the first city hall. When the city had no further use for it, it was entirely surrendered to business purposes; and in course of time it underwent great changes; the interior was completely remodelled, and an ugly mansard roof was built upon it, wholly destroying the quaint effect of the original architecture. In 1881—82 a movement to restore the building to its original appearance was begun, and in the latter year the Bostonian Society secured a lease for ten years of the entire second floor, the attics, and cupola, agreeing to maintain the principal rooms for free public exhibition; while the street floor and basement were rearranged for business purposes as before, the rentals passing to the city to which the property belongs. From the second story upwards the building now appears much as it did during the colonial period. The windows of the upper stories are modelled after the small-paned windows of the earlier times; the old picturesque pitch-roof has been reproduced; and on the State Street front, at either end of the building, are copies of the carved figures of the lion and the unicorn, formerly here, but torn down, and with other “tory signs” burned in a bonfire on the day of the first celebration of American Independence. Some over-sensitive citizens objecting to the restoration of these emblems of royalty, a brightly gilded “bird of freedom” subsequently was placed over the Washington Street front of the building. In the rooms of the second floor, an interesting collection of antiquities is on exhibition, with old portraits and paintings, and sketches of old buildings. The rooms are open free every day except Sundays and holidays.  The old State-House. The funeral of the victims of the “Boston Massacre,” who were buried in the Old Granary Burying-ground, was attended by an immense concourse of people from all parts of New England, and the impression made by the conflict upon the patriotic men of that day did not die out until the war of the Revolution had begun. The day was celebrated for several years as a memorable anniversary. The destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor was another evidence of the spirit of the people. The ships having “the detested tea” on board arrived the last of November and the first of December, 1773. Having kept watch over the ships to prevent the landing of any of the tea until the 16th of December, and having failed to compel the consignees to send the cargoes back to England, the people were holding a meeting on the subject on the afternoon of the 16th, when a formal refusal by the Governor of a permit for the vessels to pass the castle without a regular custom-house clearance was received. The meeting broke up, and the whole assembly followed a party of thirty persons disguised as Indians to Griffin’s (now Liverpool) Wharf, where the chests were broken open and their contents emptied into the dock. It has been claimed, though on very doubtful authority, that the plot was concocted in the quaint old building that stood until 1860 on the corner of Dock Square and North (formerly Ann) Street. This building was constructed of rough-cast in the year 1680, after the great fire of 1679. It was occupied by shopkeepers, and during the latter years of its existence was known as the “old feather store.” A cut of the building is here given.  Old House in Dock Square The people of the town took as prominent a part in the war when it broke out as they had takes, in the preceding events. They suffered in their commerce and in their property by the enforcement of the Boston Port Act, and by the occupation of the town by British soldiers. Their churches and burial-grounds were desecrated by the English troops, and annoyances without number were put upon them, but they remained steadfast through all. General Washington took command of the American army July 3, 1775, in Cambridge, but for many months there was no favorable opportunity for making an attack on Boston. During the winter that followed, the people of Boston endured many hardships, but their deliverance was near at hand. By a skilful piece of strategy Washington took possession of Dorchester Heights during the night of the 4th of March, 1776, where earthworks were immediately thrown up, and in the morning the British found their enemy snugly ensconced in a strong position both for offence and defence. A fortunate storm prevented the execution of General Howe’s plan of dislodging the Americans; and by the 17th of March his situation in Boston had become so critical that an instant evacuation of the town was imperatively necessary. Before noon of that day the whole British fleet was under sail, and General Washington was marching triumphantly into the town. Our sketch shows the heights of Dorchester as they once appeared; it is quite easy to see from it how completely the position commands the harbor. No attempt was made by the British to repossess the town. At the close of the war Boston was, if not the first town in the country in point of population, the most influential, and it entered immediately upon a course of prosperity that has continued with very few interruptions to the present time.  View of Dorchester Heights. The first and most serious of these interruptions was that which began with the embargo at the close of the year 1807, and which lasted until the peace of 1815. Massachusetts owned, at the beginning of that disastrous term of seven years, one third of the shipping of the United States. The embargo was a most serious blow to her interests. She did not believe in the constitutionality of the act, nor in its wisdom. The war that followed she judged to be a mistake, and her discontent was aggravated by the usurpations of the general government. Nevertheless, in response to the call for troops she sent more men than any other State, and New England furnished more than all the slave States that were so eager in support of the Administration. In all the proceedings of those eventful years Boston men were leaders. Again, in the war of the Rebellion, having been one of the foremost communities in the opposition to slavery, Boston took a leading part, this time on the popular side. In this war, in which she participated by furnishing men and means to carry it on at a distance, and in supporting it by the cheering and patriotic words of those who remained at home, her history is that of Massachusetts. Boston alone sent into the army and navy no less than 26,119 men, of whom 685 were commissioned officers. Boston retained its town government until 1822. The subject of changing to the forms of an incorporated city was much discussed as early as 1784, but a vote of the town in favor of the change was not carried until January, 1822, when the citizens declared by a majority of about six thousand five hundred out of about fifteen thousand votes, their preference for a city government. The Legislature passed an act incorporating the city in February of the same year, and on the 4th of March the charter was formally accepted. The city government, consisting of a mayor, Mr. John Phillips, as chief executive officer, and a city council composed of boards of eight aldermen and forty-eight common councilmen, was organized on May 1. During the last half century the commercial importance of Boston has experienced a reasonably steady and constant development; the greatest check upon her prosperity having been the destructive fire of the 9th and 10th of November, 1872. The industries of New England have in that time grown to immense proportions, and Boston is now the natural market and distributing-point for the most of them. The increase of population and the still more rapid aggregation of wealth tell the story far more effectively than words can do it. In 1790 the population of the town was but 18,038. The combined population of the three towns of Boston, Roxbury, and Dorchester, at intervals of ten years, is given in the following table , —

The valuation of real personal property in the last forty years show a still more notable increase. The official returns at intervals of five years show : —

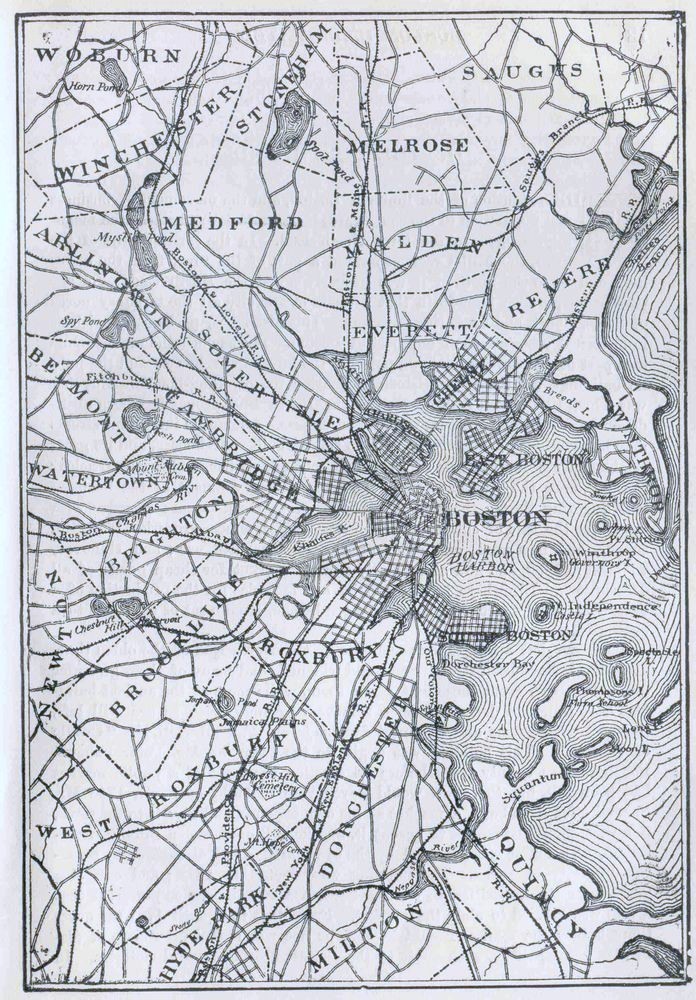

After the annexation to Boston of the city of Charlestown and the towns of West Roxbury and Brighton, the population of the united municipality became, by the census of 1870, 292,499; in 1880, according to the United States Census of that year, it had increased to 362,839. The estimated population in 1885 was fully 440,000. The valuation in 1873 was $765,818,713; in 1882, $672,497,961. State, city, and county tax rate per $1,000: 1880, $15.20; 1882, $15.10; 1883, $17.00; 1885, $12.80.  The growth of Boston proper has, notwithstanding these very creditable figures, been very seriously retarded by the lack of room for expansion. Until the era of railroads it was impracticable for gentlemen doing business in Boston to live far from its corporate limits. Accordingly it was necessary to “make land” by fifing the flats as soon as the dimensions of the peninsula became too contracted for the population and business gathered upon it. Some very old maps show how early this enlargement was commenced; and hardly any two of these ancient charts agree. During the present century very great progress has been made. All the old ponds, coves, and creeks have been filled in, and on the south and southwest the connection with the mainland has been so widened that it is now as broad as the broadest part of the original peninsula. In other respects the improvements have been immense. All the hills have been cut down, and one of them has been entirely removed. The streets which were formerly so narrow and crooked as to give point to the joke that they were laid out upon the paths made by the cows in going to pasture, have been widened, straightened, and graded. Whole districts covered with buildings of brick and stone have been raised, with the structures upon them, many feet. The city has extended its authority over the island, once known as Noddle’s Island, now East Boston, which was almost uninhabited and unimproved until its purchase on speculation in 1830; over South Boston, once Dorchester Neck, annexed to Boston in 1804; and finally, by legislative acts and the consent of the citizens, over the ancient municipalities of Roxbury, Dorchester, Charlestown, West Roxbury and Brighton. The original limits of Boston comprised but 783 acres. By filling in flats, etc., 1,048 acres have been added. By the absorption of South and East Boston and by filling the fiats surrounding these districts, 1,838 acres more were acquired. Roxbury contributed 2,700 acres, Dorchester, 5,614, Charlestown, 586, West Roxbury, 7,848, and Brighton, 2,277. The entire present area of the city is therefore about 23,661 acres, — more than thirty times as great as the original area. Meanwhile, the numerous railroads radiating from Boston and reaching to almost every village within thirty miles, have rendered it possible for business men to make their homes far away from their counting-rooms. By this means scores of suburban towns, unequalled in extent and beauty by those surrounding any other great city of the country, have been built up, and the value of property in all the eastern parts of Massachusetts has been very largely enhanced. These towns are most intimately connected with Boston in business and social relations, and in a sense form a part of the city. It is this theory that has led to the annexation of five suburban municipalities already, and that will undoubtedly lead, at no distant day, to the absorption of others of the surrounding cities and towns.  |