|

CHAPTER

XXIII.

A

journey to the mountains Long trains of camels and donkeys

Pagoda at Pale-twang Large cemetery Curious fir-tree

Agricultural productions Country people Reach the foot of the

hills Temples of Pata-tshoo Foreign writing on a wall A

noble oak-tree discovered Ascend to the top of the mountains

Fine views Visit from mandarins Early morning view Return

to Peking Descend the Pei-ho Sail for Shanghae Arrange

and ship my collections Arrive in Southampton.

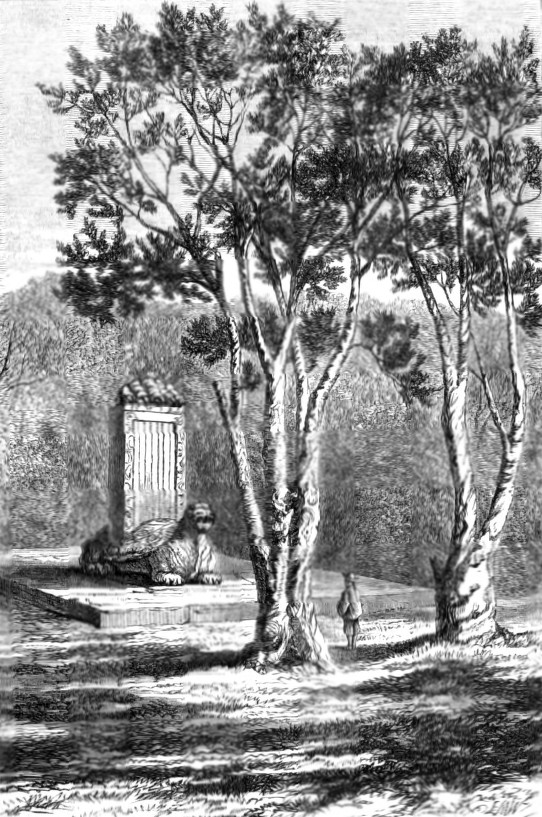

ONE of the principal objects I had in view in coming thus far north was to get a peep at the capital of China. Another inducement, and perhaps a greater one, was the hope of being able to add some new plants of an ornamental kind to my former collections. And considering the cold winters which are experienced in this part of the world, anything of that kind would have been almost certain to prove hardy in our English climate. As the nursery-gardens I had visited both at Tien-tsin and Peking were filled with well-known southern species, and as the plain through which I had passed was nearly all under cultivation and contained few trees, I was anxious to visit the mountains which bound this plain on the north and west, where I hoped to find something new to reward me for my long journey. Amongst these western mountains there are some celebrated Buddhist temples, well known to the inhabitants of Peking, and often visited by them. The Buddhist priests, in all parts of the East, preserve with the greatest care the trees which grow around their houses and temples. It was therefore probable that those at Pata-tshoo the name of the place in question would have the same tastes as their brethren in other parts of the empire, and I determined to visit them in their mountain home. Having engaged a cart for the journey, I had it packed with my bedding in the usual way, and started one morning at daybreak. Atmospheric changes are very sudden in this part of the world. The temperature, since my arrival in Peking, and even when I went to bed the night before, had been mild and warm, although not oppressive in any way. This morning, however, a north-west wind had come suddenly down, and the summer seemed to change instantly into winter. The wind was bitterly cold. Sudden changes of temperature are common in every part of China, but I never experienced such a change as this was. Greatcoats and blankets, which would have pained one to look upon a few days before, were now most welcome, and were eagerly sought after. As I preferred walking to being jolted in a springless cart, this change of temperature was far from being disagreeable. Passing out by the Fow-thing-mun a gate in the western wall of the Tartar city and through an extensive suburb, I then found myself on a country road. It was evidently the great highway between Peking and the countries to the westward. Long trains of camels and donkeys were met and passed, loaded with various kinds of merchandise. These camels were very fine animals, and much larger and apparently much stronger than those met with in Egypt and Arabia. They were covered with long hair, which is, no doubt, intended by nature to preserve them from the extreme cold of these northern regions. The tuft of long hair on the hump had a peculiar appearance as the animals moved along in the distance. One of the camels in each drove had a bell suspended from its neck, which emitted a clear tinkling sound. About nine o'clock in the morning I arrived at a long straggling town named Pale-twang, and halted to breakfast at an inn on the road-side. This place is remarkable for a pagoda about 150 feet in height, which can be seen from the ramparts of Peking, forming an excellent landmark to the traveller on this wide plain. This pagoda is octagonal, having eaves projecting on all sides, on which are hung many thousands of little bells, which are always tinkling in the wind. Its lower sides are covered with figures of ancient warriors, gods, and dragons, and heads of all sorts of animals appear to support the walls. Altogether it is one of the most remarkable specimens of Chinese architecture that have come under my observation. Four small temples are placed round its base, in two of which are some figures representing Buddhist deities, and in the other two there are tablets with inscriptions. A large temple in a ruinous condition is placed between the tower and the main road. A little further on I came to a large cemetery surrounded with high walls. As I was making some inquiries about this place, an old Chinese gentleman kindly volunteered to accompany me over it, and to explain anything I wished to know. When we entered this cemetery I was very much struck with its appearance. It covered many acres of land, and was evidently a very ancient place. Broad walks intersected it at right angles, and lofty trees of Juniper, Cypress, and Pine were growing in avenues or shading the tombs. Here was an example of taste and civilization which existed at a very early period, probably two or three hundred years ago. When the nations of Europe were crowding their dead in the dismal churchyards of populous towns, and polluting the air, the Chinese, whom we have been accustomed to look upon as only half-civilized, were forming pleasant cemeteries in country places, and planting them with trees and flowers. They were doing ages ago in China what we have been doing only of late years. At the upper end of the cemetery, and forming a termination to the broad avenues, I observed some large marble tablets, supported by the tortoise and another animal, which my guide informed me were placed there some two hundred years ago, by order of the reigning emperor, over the grave of tone of his subjects, whom he "delighted to honour." I have remarked elsewhere that a tombstone placed upon a carved representation of an animal of this kind is a sign of a royal gift. Near these royal tombstones I observed a species of Pine-tree, having a peculiar habit and most striking appearance. It had a thick trunk, which rose from the ground to the height of three or four feet only. At this point some eight or ten branches sprang out, not branching or bending in the usual way, but rising perpendicularly, as straight as a larch, to the height of 80 or 100 feet. The bark of the main-stem and the secondary stems was of a milky-white colour, peeling like that of the Arbutus, and the leaves, which were chiefly on the top of the tree, were of a lighter green than those of the common Pine. Altogether this tree had a very curious appearance, very symmetrical in form, and the different specimens which evidently occupied the most honourable places in the cemetery were as like one another as they could possibly be. In all my wanderings in India, China, or Japan, I had never seen a pine-tree like this one. What could it be? was it new? and had I at last found something to reward me for my journey to the far north? I went up to a spot where two of these trees were standing, like sentinels, one on each side of a grave. They were both covered with cones, and therefore were in a fit state for a critical examination of the species. But although almost unknown in Europe, the species is not new. It proved to be one already known under the name of Pinus Bungeana. I had formerly met with it in a young state in the country near Shanghae, and had already introduced it into England, although, until now, I had not the slightest idea of its extraordinary appearance when full grown. I would therefore advise those who have young plants of this curious tree in their collections to look carefully after them, as the species is doubtless perfectly hardy in our climate, and at some future day it will form a very remarkable object in our landscape. One of the trunks, which I measured at three feet from the ground, was 12 feet in circumference.  White-barked Pine (Pinus Bungeana) The country through which I was now passing, although comparatively flat, was gradually getting a little higher and more undulating in its general appearance. It was the harvest-time for the summer crops of millet, Indian corn, and oily grain, and the farmers were busy in all the fields gathering the crops into their barns. As I walked during the greater part of my journey, and did not always confine myself to the high road, many were the amusing adventures I met with by the way. Sometimes the simple villagers received me with a kind of vacant wondering stare, or scarcely condescended to look up from the work with which they were engaged. At other times they gathered round me, and, when they found I was civilized enough to know a little of their language, put all sorts of questions, commencing, for politeness, with those in relation to my name, my age, and my country. On one occasion, as I was passing through a village, a solitary lady, rather past the middle age and not particularly fascinating, was engaged in rubbing out some corn in front of her door. I gave her the usual salutation. She looked up from her work, and when she saw who stood before her she gave me one long earnest stare, and whether she thought I was really "a foreign devil "or a being from some other world I cannot say, but after standing for a second or two, without speaking or moving, she suddenly turned round and fled across the fields. I watched her for a little while; she never appeared to slacken her pace or to look back, and for aught I know she may be still running away! About noon I began to get near the foot of the mountains, and I could see in the distance a group of temples extending from the bottom to near the top of a hill, and nestling amongst trees. This looked like an oasis in the landscape, for all else round about was wild and barren. Shortly afterwards we left the main road, and another mile of a byway brought us to the bed of a mountain stream, dry at this season, and covered with boulders of granite, but no doubt filled with a torrent during the rains. We had now reached the famous Pata-tshoo, or eight temples, which, with their houses and gardens, are scattered all over the sides of these hills. My carter, who seemed well acquainted with the place, proceeded up the hill-side to the second range of temples, named Ling-yang-sze, and halted at its entrance. Here I was received by the head priest, a clean, respectable-looking man, who readily agreed to allow me quarters during my stay. My bedding was removed from the cart and placed in a large room, whose windows and verandah looked over the plain in the direction of Peking. The temples for Buddhist worship in this. place are small, but the rooms for the reception of travellers and devotees are numerous, and in better order than I had ever met with before. In one of these rooms a marble tablet was pointed out, which had been presented by one of the Emperors of the Ming dynasty, who had visited the place. Between the various rooms and temples were numerous small courtyards and gardens, ornamented with trees, flowers, and rockwork. Here I noticed some fine old specimens of the "Maidenhair tree" (Salisburia adiantifolia), one of which was covered all over with the well-known glycine. The creeper had taken complete possession of this forest king, and was no doubt a remarkable and beautiful object in the months of April and May, when covered with its long racemes of beautiful lilac blossoms; but the Salisburia evidently did not like its fond embraces, and was showing signs of rapid decay. A pretty pagoda stood on one side of these buildings, with numerous little bells hanging suspended from its spreading eaves, which made a plaintive tinkling noise as they were shaken by the wind. When I had rested for a little while in these pleasant quarters I informed my host that I was desirous of visiting the other temples on the hillside, and begged him to procure me the services of a guide for this purpose. A very intelligent young priest volunteered to accompany me, and our party was soon joined by eight or ten more. The different temples were like so many terraces on the hill-side, and were connected with each other by narrow walks sometimes cut out of the hill, or, where the place was steeper than usual, flights of stone steps had been made. In one of these temples, named Ta-pae-sze, I observed some writing on the wall, evidently by a foreign hand. It was dated "1832." The largest of these temples, named Shung-jaysze, has been honoured with a mark of royal favour in the shape of a tablet resting on a carved tortoise. Here too is pointed out, with no little pride, a room in which the favourite Emperor of the present dynasty, Kein-lung, slept when he visited the temple. Fine views of the plain are obtained from the front rooms; and a large bridge, named Loo-co-jou, was pointed out to me in the distance. On the sides of these hills I met with a new oak-tree (Quercus sinensis) of great interest and beauty. It grows to a goodly size sixty to eighty feet, and probably higher has large glossy leaves, and its bark is rough, somewhat resembling the cork-tree of the south of Europe. Its acorns were just ripe, and were lying in heaps in all the temple-courts. They are eagerly bought up by traders, and are used in the manufacture of some kind of dye. I secured a large quantity of these acorns; and they are now growing luxuriantly in Mr. Standish's nursery at Bagshot. As this fine tree is almost certain to prove perfectly hardy in Europe, it will probably turn out to be one of the most valuable things I have brought away from Northern China. A species of maple and an arbor-vitζ of gigantic size were also met with on these hills, apparently distinct from the species found in the more southern provinces of the Chinese empire, and walnut-trees were observed covered with fruit in some of the temple-gardens. Amongst wild plants on these hill-sides there was a pretty species of Vitex resembling V. agnus-castus, and a neat little fern (Pteris argentea) was growing on some old walls. Amongst the plants cultivated for their flowers by the priests, I observed oleanders, moutans, pomegranates, and such things as I had already noticed in the gardens of Peking. A marble bridge of great age spanned the bed of a mountain stream, which was dry at this season; and examples of nature's rockwork, looking almost as fantastic as if it had been artificial, were met with in many places. High above all the other temples, and nearly at the top of these hills, was a small one named Pouchoo-ting. The most charming views were obtained from this situation, not only over the vast plain which lay beneath us, but also of the summer palace of Yuen-ming-yuen, rendered famous by the scenes enacted there during the late war. Passing out of the grounds of this place, I now commenced the ascent of the hills behind it, and kept on until I reached the highest point of their summits. Here I sat down upon a cairn of stones to enjoy the scene which lay spread out before me. It was a lovely autumnal day, the air was cold and bracing, and the atmosphere so clear that objects at a very great distance were distinctly visible. Looking to the eastward I could see the walls and watchtowers of Peking, and the roofs of its yellow palaces. On my left hand I looked down upon the ruins of the palace of Yuen-mingyuen. A little hill in the vicinity of the Summer Palace, and the lake of Koo-nu-hoo, were distinctly visible from where I was stationed. On my right, to the westward, a small stream appeared winding its way amongst the hills in the direction of the plain, where it was spanned by a bridge of many arches the Loo-co-jou I have already mentioned. In front, to the south, the mighty plain of Tien-tsin extended far away to the distant horizon, dotted here and there with pagodas, but without a mountain or a hill on any part of its surface. Behind me, to the north, were hills and mountains of every size and form, separated by valleys in which I observed, in some places, little farm-houses and patches of cultivated land. The tops of these mountains, and by far the greater portion of their sides, were bleak and barren, yielding only some wiry grasses, a species of stunted thorny Rhamnus (? R. zizyphus); and here and there, at this season, a little Campanula, not unlike the Blue Bells of Scotland, showed itself amongst the clay-slate rocks which were cropping out over all the hills. In the spring there are no doubt many other kinds of flowers which blossom unseen amongst these wild and barren mountains. This map of nature which lay before me was one of no common kind. It reminded me of the views from the outer ranges of the Himalayas over the plains of Hindostan, with this difference, that these Chinese mountains rival in barren wildness many parts of the Scottish Highlands. When I was in full enjoyment of the scenery around and beneath me, my companions pointed to the setting sun, and suggested that it was time to go down to the temples. Night was already settling down upon the vast plain, and objects were becoming gradually indistinct there, while the last rays of the setting sun still illuminated the peaks of the western mountains. When we got back to the temple the good priest pretended to have been greatly alarmed on account of our long absence and the darkness of the night. We might have lost our way or missed our footing amongst the mountains and ravines. However, an excellent Chinese dinner was soon smoking on the table; and although chopsticks had to supply the places of knives and forks, the air of the mountains had furnished me with a tolerable appetite, and made me quite indifferent to the deprivation. After dinner I was honoured with the company of some high officials of the district, who came to inquire what my objects were in visiting this part of the country; but as my servant had already informed them that I had come from the Yamun of the great English Minister, they were easily satisfied, and did not even ask for a sight of my passport. Sundry cigars and a glass or two of wine put them in capital humour, and we parted very good friends. When the mandarins left me the priests and others in the temple retired to rest, and shortly afterwards the only sounds which fell upon my ear were caused by the wind rustling among the leaves of the surrounding trees and the tinkling of the bells which hung from the eaves of the pagoda. Fatigued with the exertion of the day I retired early to rest, and nothing occurred during the night to disturb my slumbers. Next morning I was up before the sun, and enjoyed a view of the vast plain as it was gradually lighted up by the early rays. It was curious to see the light chasing away the darkness and exposing to view the pagodas, bridges, and towers which but a short time before had been invisible. During the day I visited some temples and gardens on the other side of a valley, and secured a supply of the plants of the district for the herbarium, and the seeds of several trees of an ornamental and useful character worth introducing into Europe. The people amongst these hills seemed to be a quiet and inoffensive race, miserably poor, having only the bare necessaries of life and none of its luxuries. The Buddhist priest were apparently much better off, being, no doubt, upheld and supported by their devotees among the wealthier classes of the capital, who came to enjoy the scenery amongst the hills and to worship in the temples. After a pleasant sojourn of two days in this part of the country I returned to Peking. As on the way out, long trains of donkeys and camels were met and passed on the road, many of them being laden with coal, which is found in abundance amongst these western hills. On the way back I paid another visit to the cemetery of Pale-twang, and obtained a fresh supply of the seeds of the curious fir-tree I have already described. Having finished my work in Peking and packed up the collections I had formed there, I left that city on the 28th of September, and considered myself as once more "homeward bound." My friend Dr. Lockhart accompanied me several miles on my way. With many good wishes for a prosperous voyage home the worthy medical missionary bade me adieu, and returned to his arduous duties in the far-famed capital of Cathay. As it was my intention to return to Tien-tsin by boat down the Pei-ho river, I had taken the road which leads from Peking to the pity of Tong-chow, at which place boats were to be procured for the voyage. A short distance on the north-west of Tong-chow I passed the now celebrated bridge and battle-field of Pali-kao. On arriving at Tong-chow I found no difficulty in engaging a boat, and we sailed rapidly and pleasantly down the stream. As opportunities for leaving Tien-tsin for the south were few and uncertain, I had to remain some days there before I could get onwards. At last, owing to the kindness of the French commandant at Taku, I procured a passage in the despatch boat 'Contest,' and reached Shanghae on the 20th of October. Here I found my Japanese collections (which I had left in Mr. Webb's garden) in excellent condition, and I employed the next fortnight in preparing them for their long voyage home round the Cape of Good Hope. The collections were divided into two equal portions, and, as a precautionary measure, were put on board of two ships. These cases have now reached England, and nearly every plant of importance has been introduced alive. Long shelves filled with these rare and valuable trees and shrubs of Japan have been exhibited during the last two summers by Mr. Standish at the different botanical and horticultural exhibitions in the metropolis, and already many of the earlier introductions have been distributed all over Europe. Some especial favourites, which I did not like to trust to the long sea journey round the Cape, were brought home by the overland route under my own care. One of these is a charming little saxifrage, having its green leaves beautifully mottled and tinted with various colours of white, pink, and rose. This will be invaluable for growing in hanging baskets in greenhouses or for window gardening. I need not tell now how I managed my little favourites on the voyage home; how I guarded them from stormy seas, and took them on shore for fresh air at Hongkong, Ceylon, and Suez; how I brought them through the land of Egypt and onwards to Southampton. More than one of my fellow-passengers by that mail will remember my movements with these two little hand greenhouses. On the 2nd of January, 1862, the Peninsular and Oriental Company's ship 'Ceylon,' Captain Evans, steamed into the dock at Southampton, and thus ends the narrative of my visit to Zipangu and Cathay. |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2011

(Return to Web Text-ures)