| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

IX.

Leave

Yedo — Mendicant nuns — Place of execution — Its appearance in

the days of Kæmpfer — Visit to a famous temple — Field crops by

the way — Begging priests — Pear-trees — Holy water — Temple

of Tetstze — Its priests and devotees — Inn of "Ten Thousand

Centuries" — Kind reception — Waiting-maids and refreshments

— Scenes on the highway — Relieved from my yakoneen guard — New

plants added to my collections — Names of the most valuable —

Ward's cases, their value — Plants shipped for China — Devout

wishes for their prosperous voyage.

WHILE engaged in making observations on the city of Yedo and the country around it, I had been daily adding to my collections of new trees and shrubs. Now and then a bit of ancient lacquer-ware, or a good bronze, took my fancy, and was carefully put by. The gardens I have already described were visited frequently, and each time something new was discovered and brought away. Mr. J. G. Veitch, the son of one of our London nurserymen, had also been in Yedo, endeavouring to procure new plants for his father, and consequently our wants in this way were generally known amongst the people. Almost every morning, during my stay at the Legation, collections of plants were brought for sale, and it was seldom that I did not find something amongst them of an ornamental or useful character that was new to our English gardens. This, however, could not last for ever; and the time came when I had apparently exhausted the novelties in the capital of Japan. Baskets were now procured, in which the plants were carefully packed and sent down by boat to Yokuhama, where Ward's cases were being made, in which they were to be planted and sent home to England. On

the 28th of November I left the hospitable

quarters of the

English minister, on my return to Kanagawa. I returned by the way I

came — along the Tokaido, or great highway of Japan. Again we

passed through the scenes I have already described: beggars on the

wayside, mendicant priests, Bikuni or begging nuns, travelling

musicians, coolies carrying manure as in China, lumbering carts1

and pack-horses, and travellers of all ranks, were met and passed on

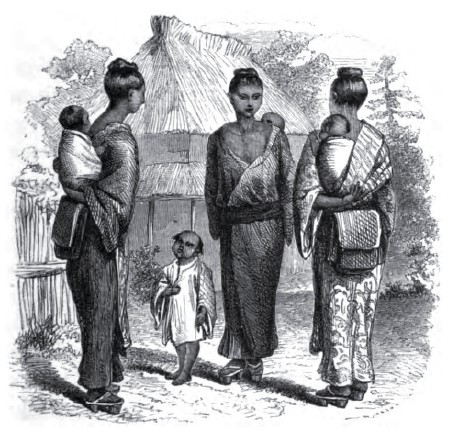

the road.  Bikuni, or Mendicant Nuns Here are some Bikuni, or mendicant nuns, sketched on the spot by my friend Dr. Dickson. Kæmpfer gives us the following description of this religious order: — "They live under the protection of the nunneries at Kamakura2 and Miaco, to which they pay a certain sum every year, of what they get by begging, as an acknowledgment of their authority. They are, in my opinion, much the handsomest girls we saw in Japan. The daughters of poor parents, if they be handsome and agreeable, apply for and easily obtain this privilege of begging in the habit of nuns, knowing that beauty is one of the most persuasive inducements to generosity. The Jamabo, or begging mountain priests, frequently incorporate their own daughters with this religious order, and take their wives from among these Bikuni. Some of them have been bred up as courtezans, and, having served their time, buy the privilege of entering into this religious order, therein to spend the remainder of their youth and beauty. They live two or three together, and make an excursion every day a few miles from their dwelling-house. They particularly watch people of fashion, who travel in norimons, or in kangos, or on horseback. As soon as they perceive somebody coming they draw near and address themselves, not all together, but singly, every one accosting a gentleman by herself, and singing a rural song; and if he proves very liberal and charitable, she will keep him company and divert him for hours. . . . They wear a large hat to cover their faces, which are often painted, and to shelter themselves from the heat of the sun." A number of shops, established for the sale of sea-shells, were observed on the road-side, but they did not contain many species of interest. Dried fruits for sale were numerous and plentiful, such as oranges, pears, gingko-nuts (Salisburia adiantifolia), capsicums, chesnuts, and acorns. The fruit of Gardenia radicans is used here as a yellow dye, in the same way as in China. Amongst vegetables I noticed carrots, onions, turnips, lily-roots, ginger, gobbo (Arctium gobbo), nelumbium-roots, Scirpus tuberosus, arums, and yams. Fish of excellent quality was exposed for sale in large quantities. A little way out of Sinagawa my yakoneens pointed out the place where criminals are executed. It is an uninviting-looking piece of ground close by the highway. I find that Kæmpfer notices the same spot as observed by the Dutch embassy upwards of two hundred years ago. Near to Sinagawa they passed "a place of public execution, offering a show of human heads and bodies, some half putrefied and others half devoured — dogs, ravens, crows, and other ravenous beasts and birds, uniting to satisfy their appetites on these miserable remains." On the present occasion I did not notice any of these revolting sights, and it is to be hoped that the Japanese have, like ourselves, become less addicted to judicial blood-shedding than they were at the time of Kæmpfer's visit. It will be remembered that such exhibitions were not uncommon amongst Western nations at a later period even than that alluded to. When we had crossed the river Lop we put up our horses at the inn of "Ten Thousand Centuries," and proceeded on foot to visit a famous Buddhist temple situated about a mile and a half from the ferry. Our road led us through fields and gardens, all in a high state of cultivation. Rice appeared to be the staple summer crop of the low land of this district. Many gardens of pear-trees were also seen on the road-side. The branches of these trees were trained horizontally when about five or six feet from the ground, sometimes singly in the shape of a round table, or in groups in the form of an arbour. The branches are supported by a rude trelliswork of wood. The pear of the district is a pretty round brown kind, good to look upon, but only fit for kitchen use. There are no fine melting pears in Japan; at least none came under my notice during my stay in the country. On the roadside there were many little shops in which tea and dried fruits were exposed to tempt the weary pilgrim on his way to worship at the temple. Begging priests were also passed, ready to bestow prayers and blessings on the heads of those who gave them alms. As we approached the sacred building, one of my yakoneens ran before to announce our arrival. On entering the main gateway there was a tank of holy water on our right hand. Every devotee, on entering, visits the holy well, and sprinkles himself with water before he enters the temple. For this privilege he pays a small sum, the amount expected being in accordance with the means of the giver. In most cases the poor give only a few cash of the country, about the value of a farthing of our money. My attendant yakoneens did not fail to perform the ceremony like good Buddhists, after which we ascended the broad flight of steps which led up to the main hall of the temple. Many native visitors came in while we were there, and each one, as he reached the door of the edifice, was observed to bow low before its altars, and to mutter some prayers. Inside there were a number of priests of the Buddhist faith, who had evidently an eye to the good things of this world, and who were busily engaged in selling books and pictures connected with the temple to the ignorant and superstitious who came to worship at its altars. The temple itself appeared to be a strong and massive structure. Huge paper lanterns were hanging from the roof, and a few Buddhist deities were observed on the altars. Otherwise it was not remarkable, and was far inferior to the chief temples commonly met with in China. When we got back to the inn of "Ten Thousand Centuries" a number of the waiting-maids of the place came running out to welcome us with the usual "Ohio," or "Good morning; how do you do?" of the Japanese. I know that the main object of all this excessive civility is to bring custom to the establishment, and sundry itzeebus3 out of the pockets of the traveller; but after all, there is much gratification in a kind reception, and it is not worth while to look too closely into the motives of those who give it. In the present instance we had had a long walk over a dry hard road, the sun had been hot, and we were glad to accept the invitation given to us by the pretty damsels to enter the inn and refresh ourselves after our journey. The same scene was now exhibited as I have already described at the "Mansion of Plum-trees." A low square table was placed before me, covered with different kinds of sweet cakes, dried fruits, and cups of tea. The young girls of the tea-house, kneeling in front and on each side of me, poured out my tea, and begged me to eat of the cakes and fruits, while one of them busied herself in taking the shells off some hard-boiled eggs, dipping them in salt, and putting them to my mouth. Surely all this was enough to satisfy and refresh the most weary traveller, and to send him on his way rejoicing. But the best of friends must part at last, so I was obliged to bid adieu to mine host and his fair waiting-maids of the "Ten Thousand Centuries," and pursue my way to Kanagawa. Nothing particularly worthy of notice presented itself during the remainder of my journey. The same motley groups and queer-looking travellers were met and passed on the highway; dogs barked, and children ran out of the houses to look at the foreigner, and to cry out, as loudly as their little lungs would permit, "Anato, Ohio." The number of little girls, each having a child tied on her back, was one of the most amusing sights during our progress. As these ran hobbling along, and the little heads of the children bobbed about, in danger apparently of being shaken off, one could not help laughing. On reaching the temple in Kanagawa, in which my quarters were, my yakoneen guard informed me that their presence was no longer necessary, and I was free again to roam about by myself in any direction I pleased. I must confess that, however highly honoured I had felt during my visit to Yedo, by having a mounted armed guard attending me wherever I went, yet the departure of the yakoneens was a decided relief, and greatly did I enjoy a return to my former lowly estate.  Nursery Maids Mr. M'Donald, of Her Majesty's Legation in Yedo, from whom I had received much kindness and assistance, had been good enough to forward my collection of plants in boats to Kanagawa, and these arrived in safety. My guide Tomi had been employed during my absence by making collections of seeds and plants; but I am bound to confess that, according to the accounts I received of his proceedings during my absence, it appeared his favourite saki had had more attractions for him than natural history. As I had now secured living specimens and seeds of all the ornamental trees and shrubs of this part of Japan which I was likely to meet with at this season of the year, the whole were removed across the bay to Yokuhama, and placed for safety in Dr. Hall's garden, until Ward's cases were ready for their reception. The collection which had been got together at this time was a most remarkable one. Never at any one time had I met with so many really fine plants, and they acquired additional value from the fact that a great portion of them were likely to prove suitable to our English climate. Amongst conifers there was the beautiful parasol fir (Sciadopitys verticellata), Thujopsis dolabrata, Retinospora obtusa and R. pisifera, Nageia ovata, several new pines and cypresses, and varieties of almost all these species having variegated leaves. Amongst other shrubs there was a charming species of Eurya, having broad camellia-looking leaves, beautifully marked with white, orange, and rose colours; a pretty variegated Daphne; several species of privets, yews, hollies, box, and ferns. In addition to these there were two or three new species of Skimmia — shrubs which bear sweet-scented flowers, and become covered with red berries, like the holly, during winter and spring; a palm with variegated leaves, a noble species of oak, some new Weigelas, and a number of curious chrysanthemums. This list of beautiful trees and shrubs, all new to English gardens, may appear a long one, yet I must add to it several representatives of other two genera which are particularly worthy of notice. The first is a shrub or small tree called Osmanthus aquifolius. This genus is closely allied to the olive; it produces sweet-scented white flowers, and has dark-green prickly leaves like the holly. Curiously enough, the leaves on the upper branches and shoots of the Osmanthus are produced without spines, exactly as we see on old holly-trees. All the species of Osmanthus have variegated varieties in Japan, many of which are very beautiful objects for garden decoration. The other genus to which I would call attention is the well-known Aucuba. In Europe we know only the variegated variety of Aucuba japonica, which is one of the most useful of our evergreens, inasmuch as it is perfectly hardy in our climate, and flourishes even in the smoke of large towns where our indigenous shrubs refuse to live. But in the shaded woods near the capital of Japan I met with the true species of Aucuba japonica, of which the variegated one of our gardens is, no doubt, only a variety. This species has beautiful shining leaves of the brightest green, and becomes covered, during the winter and spring months, with bunches of red berries, which give it a pretty appearance. In fact, the Aucuba of the woods near Yedo is the "Holly of Japan." I frequently met with hedges formed of this plant, which were very ornamental indeed. In the woods there are numerous varieties of both sexes, some of which show the faintest traces of variegation, while others are nearly as much marked as the Aucubas found in our English gardens. In addition to the Aucubas found in a wild state, I had, in this collection, several garden varieties, with distinct and beautiful variegation, and the male plant of our common garden species, to which I have alluded in an earlier chapter, the introduction of which is likely to add much to the beauty and interest of that useful shrub, inasmuch as we may now expect to have it covered, during winter and spring, with a profusion of crimson berries. Many other species of interest might be named in the collection which I had now got together, but the above will suffice to show how fruitful the field for selection had been in and near the capital of Japan. From the list which I have given, no one will be surprised when he hears others tell of the lovely sylvan scenery of the Japanese islands. I have already endeavoured to give a faint idea of such scenery; and it was now my intention to transfer to Europe and America examples of those trees and shrubs which produce such charming effects in the Japanese landscapes. But the latter part of the business was no easy matter. To go from England to Japan was easy enough; to wander amongst those romantic valleys and undulating hills was pleasure unalloyed; to ransack the capital itself, although attended by an armed guard, was far from disagreeable; and to get together such a noble collection as I have just been describing was the most agreeable of all. The difficulty — the great difficulty — was to transport living plants from Yedo to the Thames, over stormy seas, for a distance of some 16,000 miles. But, thanks to my old friend Mr. Ward, even this difficulty can now be overcome by means of the well-known glass cases which bear his name. Ward's cases have been the means of enriching our parks and gardens with many beautiful exotics, which, but for this admirable invention, would never have been seen beyond those countries to which they are indigenous. In a foreign country, however, even Ward's cases cannot be made without some difficulty. The carpenter who contracted to make the framework of the cases would have nothing to do with the glazing, because he did not understand it. A Dutch carpenter, residing in Yokuhama, undertook to do the glazing, but unfortunately broke his diamond and could not procure another to cut the glass! Luckily, however, these difficulties were got over at last, and a sufficient number of cases were got ready to enable me to carry the collection on to China. The steam-ship 'England,' Captain Dundas, being about to return to Shanghae, I availed myself of the opportunity to go over to that port with my collections, in order to ship them for England, there being as yet no means of sending them direct from Japan. Mr. Veitch had also put his plants on board the same vessel, so that the whole of the poop was lined with glass cases crammed full of the natural productions of Japan. Never before had such an interesting and valuable collection of plants occupied the deck of any vessel, and most devoutly did we hope that our beloved plants might be favoured with fair winds and smooth seas, and with as little salt water as possible — a mixture to which they are not at all partial, and which sadly disagrees with their constitutions

1 Carts are used extensively all over the city and suburbs of Yedo, but are not met with on country roads. 2 Kamakura. See Chap. XIV. 3 A silver coin of Japan, worth about eighteenpence. |