| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

V.

The

city of Yedo — Hill of the god Atango — Magnificent view of the

city from its summit — "Official quarter" — Broad

streets — Castles of the feudal princes — The inner circle —

Moats and massive walls — Clumps of trees — No embrasure or guns

visible — Use of the moats and ramparts — Murder of the Regent or

Gotiro — Fate of the murderers — The Harikari — Castle of the

Emperor — Kæmpfer's description — "Belle Vue" —

Population of Yedo — Size of the city.

ON the day after my arrival in Yedo Mr. Alcock was good enough to invite me to accompany him in a ride through some of the most interesting parts of the city. The Legation is situated in the south-west suburb, and the main portion of the great city lies to the eastward from our starting point. There was nothing to indicate to a stranger the point where the western suburb ended and the city commenced; indeed, as it has been justly observed, "the suburb of Sinagawa merges into Yedo much in the same way as Kensington straggles into London." Taking then an easterly course, a portion of our road led us through lanes fringed with fields and gardens, and through streets somewhat resembling those of a country town in England. During the first part of our route there was nothing particularly striking to attract our attention. Soon, however, we arrived at a spot of great interest. This was a little hill, one of the highest of the many hills which are dotted about all over the city. Its name was Atango-yama, which means the "Hill of the god Atango." On its summit there is a temple erected to the idol, and a number of arbours where visitors, who come either for worship or for pleasure, can be supplied with cups of tea. Leaving our horses at the foot of the hill, we ascended it by a long flight of stone steps, which were laid from the base to the summit. When we arrived at the top of the steps, we found ourselves in front of the temple and its surrounding arbours. Here we were waited upon by blooming damsels, and invited to partake of sundry cups of hot tea. But the temple, the arbours, and even our fair waiting-maids, were for the time disregarded as we gazed upon the vast and beautiful city which lay below us spread out like a vast panorama. Until now I had formed no adequate idea of the size of the capital of Japan. Before leaving China I had heard stories of its great size, and of its population of two millions; but I confess I had great doubts as to the truth of these reports, and thought it not improbable that, both as to size and population, the accounts of Yedo might be much exaggerated. But now I looked upon the city with my own eyes, and they confirmed all that I had been previously told.

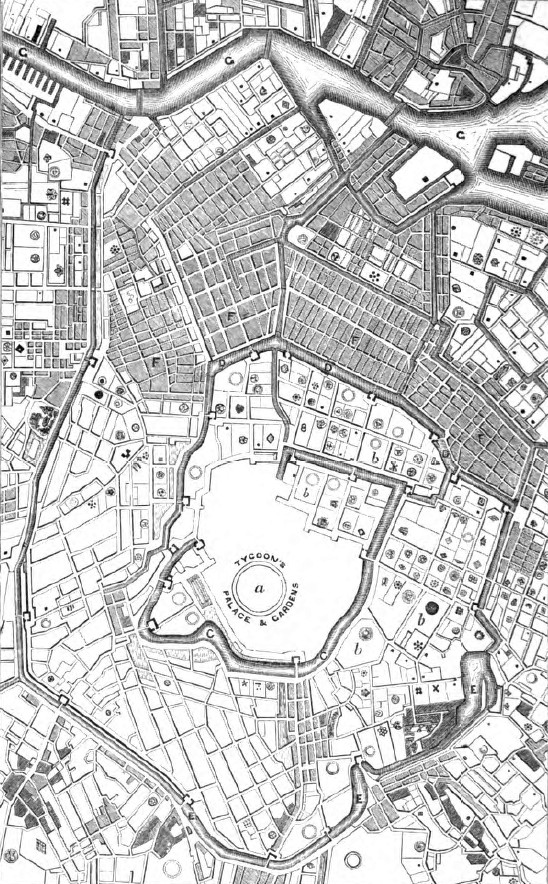

Plan Of Central Portion of the City of Yedo

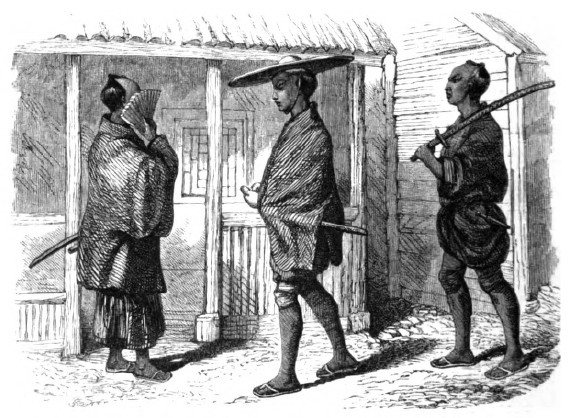

Looking back to the south-west over the wooded suburb of Sinagawa from which we had just come, and gradually and slowly carrying our eyes to the south and on to the east, we saw the fair city of Yedo extending for many miles along the shores of the bay, in the form of a crescent or half-moon. It was a beautiful autumnal afternoon, and very pretty this queen of cities looked as she lay basking in the sun. The waters of the bay were smooth as glass, and were studded here and there with the white sails of fishing-boats and other native craft; a few island batteries formed a breastwork for the protection of the town; and far away in the distance some hills were dimly seen on the opposite shores. Turning from the east towards the north, we looked over an immense valley covered with houses, temples, and gardens, and extending far away almost to the horizon. A wide river, spanned by four or five wooden bridges, ran through this part of the town and emptied itself into the bay. On the opposite side of a valley, some two miles-wide and densely covered with houses, we saw the palace of the Tycoon and the "official quarter" of the city, encircled with massive stone walls and deep moats. Outside of this there are miles of wide straight streets and long substantial barn-looking buildings, which are the town residences of the feudal princes and their numerous retainers. To the westward our view ranged over a vast extent of city, having in the background a chain of wooded hills, whose sloping sides were covered with houses, temples, and trees. A large and populous portion of Yedo lies beyond these hills, but that was now hidden from our view. Such is the appearance which Yedo presents when viewed from the summit of Atango-yama. This hill now bears the modern title of "Grande Vue," and well it deserves the name. After we had enjoyed this magnificent view for some time, we descended by the stone steps and resumed our ride. Our road now skirted a hill clothed with noble timber-trees and surrounded with walls. This was the Imperial cemetery. A short distance beyond this we crossed the first or outer moat, and were then in the "official quarter," amongst the residences of the Daimios and their retainers. Here the streets are wide, straight, and cleanly kept, and altogether have quite a different appearance from those we had already passed through. Good drains are carried down each side to take off the superfluous water. All we saw of the houses of the Daimios was the outer walls, the grated windows, and the massive-looking doors, many of them decorated with the armorial bearings of their owners. These buildings were low — generally two stories high; their foundations and lower walls were formed of massive stonework, and the upper part of wood and chunam. Judging from the general length of the outer street walls, the interior of these places must be of great size; indeed such must necessarily be the case, to enable them to accommodate the large number of retainers which these princes always keep about them. As we rode along, many of these retainers showed themselves at the grated windows. It might be only fancy on my part, but I thought I could discern little good-will or friendly feeling towards ourselves in their countenances. I have just stated that we crossed a bridge over a deep moat before entering the Daimios' quarter. In order to give an idea of the plan of this part of the city, I may compare the moat to a rope loosely coiled; the end of the outer coil dipping as it were into the river, and supplying the whole with water. It is not correct to say, as is sometimes said, that there are three concentric circles, each surrounded by a moat. The Tycoon's palace and the offices of his ministers are situated in the centre of the coil, while the outer and wider portion encircles the mansions of the feudal princes. The second or inner moat and enclosure was now in view in front of us, with its houses and palaces on rising ground. On the inner side of this circling-moat there are high walls on the water's edge formed of large blocks of stone, of a polygonal form, and nicely fitted into each other without the aid of lime or cement. This is a favourite mode of building in Japan in all cases in which stone is used. The plan is probably adopted in order to render such structures more secure in a country like this which is so subject to earthquakes. In some places sloping banks of green turf rise steeply from the edge of the moat, and are crowned at the top with a massive wall. A landslip in these banks, however, showed that the wall which apparently crowned their summits had its foundation far below, and that the banks themselves had been formed in front of the wall. On many of these green banks there are groups of juniper and pine trees, while inside the wall itself tall specimens of the same trees rear their lofty heads high above the ramparts. No embrasures or places for guns were observed in these walls, although one would imagine they had been erected for the purposes of defence. Kæmpfer, however, assigns another reason; he says, "Yedo is not enclosed with a wall, no more than other towns in Japan, but cut through by many broad canals, with ramparts raised on both sides, and planted at the top with rows of trees, not so much for defence as to prevent the fires — which happen here too frequently — from making too great a havoc." A few months previous to the time of my visit, the Gotiro, or Regent of the Empire, had been waylaid and murdered in open day, as he was proceeding from his residence to his office in the inner quarter. The scene of this tragedy was pointed out to me. A writer in the Edinburgh 'Review' gives the following graphic account of this horrid murder: — "Within the second moated circle facing the bay, the causeway leads over a gentle acclivity, near the summit of which, lying a little backward, is an imposing gateway, flanked on either side with a range of buildings, which form the outer screens of large courtyards: Over the gates, in copper metal, is the crest of the noble owner — the chief of the house of Ikomono, in which is vested the hereditary office of Regent, whenever a minor fills the Tycoon's throne. From the commanding position of this residence a view is obtained of a long sweep of 'the rampart; and midway the descent ends in a long level line of road. Just at this point, not 500 yards distant, is one of the three bridges across the moat, which leads into the inner enclosure, where the castle of the Tycoon is situated. It was about ten o'clock in the morning of the 24th of March, while a storm of alternate sleet and rain swept over the exposed road and open space, offering little inducement to mere idlers to be abroad, that a train was seen to emerge from the Gotiro's residence. The appearance of the cortege was sufficient to tell those familiar with the habits and customs of the Japanese that the Regent himself was in the midst, on his way to the palace, where his daily duties called him. Although the numbers were inconsiderable, and all the attendants were enveloped in their rain-proof cloaks of oiled paper, with great circular bats of basket or lacquered ware tied to their heads, yet the two standard-bearers bore aloft at the end of their spears the black tuft of feathers, distinctive of a Daimio, and always marking his presence. A small company of officers and personal attendants walk in front and round the foremost norimon, while a troop of inferior office-bearers follow, grooms with led horses, extra norimon-bearers, baggage-porters — for no officer, much less a Daimio, ever leaves his house without a train of baggage — empty or full, they are essential to his dignity. Then there are umbrella-bearers — the servants of the servants — along the line. The cortege slowly wound its way down the hill, for the roads were wet and muddy even on the high ground, while the bearers were blinded by the drifting sleet, carefully excluded only from the noromons by closed screens. Thus suspended in a sort of cage, just large enough to permit a man to sit cross-legged, the principal personage proceeded on his way to the palace. Little, it would seem, did either he or his men dream of possible danger. How should they, indeed, on such a spot, and for so exalted a personage? No augur or soothsayer gave warning to beware of the 'Ides of March.' . . . . The edge of the moat is gained. A still larger cortége of the Prince of Kiu-siu, one of the royal brothers, was already on the bridge, and passing through the gate on the opposite side, while, coming up from the causeway, at a few paces distant, was the retinue of the second of these brothers, the Prince of Owari. The Gotiro was thus between them at the foot of the bridge, on the open space formed by the making of a broad street, which debouches on the bridge. A few straggling groups, enveloped in their oil-paper cloaks, alone were near, when suddenly one of these seeming idlers flung himself across the line of march, immediately in front of the Regent's norimon. The officers of his household, whose place is on each side of him, rushed forward at this unprecedented interruption — a fatal move, which had evidently been anticipated, for their place was instantly filled with armed men in coats of mail, who seemed to have sprung from the earth — a compact band of some eighteen or twenty men. With flashing swords and frightful yells, blows were struck at all around, the lightest of which severed men's hands from the poles of the norimon, and cut down those who did not fly. Deadly and brief was the struggle. The unhappy officers and attendants, thus taken by surprise, were hampered with their rain gear, and many fell before they could draw a sword to defend either themselves or their lord. A few seconds must have done the work, so more than one looker-on declared; and before any thought of rescue seemed to have come to the attendants and escorts of the two other princes, both very near (if, indeed, they were total strangers to what was passing), one of the band was seen to dash along the causeway with a gory trophy in his hand. Many had fallen in the mêlée on both sides. Two of the assailants, who were badly wounded, finding escape impossible, it is said, stopped in their flight, and deliberately performed the Harikari,1 to the edification of their pursuers; for it seems to be the law (so sacred is the rite, or right, whichever may be the proper reading) that no one may be interrupted, even for the ends of justice. These are held to be sufficiently secured by the self-immolation of the criminal, however heinous the offence; and it is a privilege to be denied to no one entitled to wear two swords. Other accounts say that their companions, as a last act of friendship, despatched them to prevent their falling into the hands of the torturer. Eight of the assailants were unaccounted for when all was over; and the remnant of the Regent's people, released from their deadly struggle, hurried to the norimon to see how it fared with their master in the brief interval, to find only a headless trunk. The bleeding trophy carried off had been the head of the Gotiro himself, hacked off on the spot. But strangest of all these startling incidents, it is further related that two heads were found missing, and that which was seen in the fugitive's hand was only a lure to the pursuing party, while the true trophy had been secreted on the person of another, and was thus successfully carried off. The decoy paid the penalty of his life. After leading the chase through a first gateway down the road, and dashing past the useless guard, he was finally overtaken; the end for which he had devoted himself having, however, as we have seen, been accomplished. Whether this be merely a popular version or the simple truth, it serves to prove what is believed to be a likely course of action; and how ready desperate men are to sacrifice their lives for an object. The officer in command of the guard, who allowed his post to be forced, was ordered the next day to perform the Harikari on the spot. The rest of the story is soon told. All Yedo was thrown into commotion. The wardgates were all closed; the whole machinery of the government in spies, police, and soldiers, was put in motion, and in a few days it was generally believed the whole of the eight missing were arrested, and in the hands of the torturer. What revelations were wrung from them, or whether they were enabled to resist the utmost strain that could be put upon their quivering flesh and nerve, remains shrouded in mystery." Riding onwards, and keeping the citadel on our left, we passed two or three bridges which crossed the inner moat, and led into the palace and offices of the ministers. These personages and their servants may be seen daily going to office about nine or ten o'clock in the morning, and returning to their homes about four in the afternoon, much like what occurs at our own public offices. Some walk to office, some ride on horseback, and others go in norimons. Almost every man we met was armed with two swords. Now and then we met or passed a Daimio, or official of rank, accompanied by his train of retainers, armed with swords, spears, and matchlocks, and with the usual amount of luggage, large umbrellas, led horses, and other signs of his rank. No foreign visitor to Yedo is allowed to enter the sacred precincts of the inner enclosure which we were now riding round. A short time before this, a portion of the palace of the Emperor had been burned down, and it was now being rebuilt. Judging from the part of it which came under my observation in the, distance, it did not seem a very imposing structure. Kæmpfer writes in glowing terms of the palace of his day: "It had a tower many stories high, adorned with roofs and other curious ornaments, which make the whole castle look, at a distance, magnificent beyond expression, amazing the beholders, as do also the many other beautiful bended roofs, with gilt dragons at the top, which cover the rest of the buildings within the castle." As this work, however, professes only to give the reader a description of what came under my own observation, I must leave to others the description of the interior of the Tycoon's castle. We had approached the citadel on the south, passed round it to the eastward, and were now on a rising ground on the north. Here another of those splendid views over the city and bay was obtained. This point has been named "Belle Vue" by foreigners, and deservedly so. It would be a mere repetition of what I saw from the "Hill of Atango" to describe the scene which we now again beheld. Suffice it to say, that a vast city, bounded on one side by a beautiful bay, and on the other by the far off horizon, lay spread out beneath us. The land appeared studded all over with gardens; undulating ground and little hills were dotted about in every direction, crowned with evergreen trees, such as oaks and pines, and, although it was now far on in November, there was nothing to indicate the winter time in Yedo. The population of this fine city has been estimated at about two millions of souls. The extent of ground covered by Yedo, and the main parts of its suburbs, has been stated by Kæmpfer, on Japanese authority, to be about sixteen English miles long, twelve broad, and fifty in circumference. Judging from a native map of the city now before me, and from having ridden through it in all directions, I think the following is about its true size: From the southern suburb of Sinagawa to the north-eastern suburb the distance is about twelve miles, and from east to west it is about eight miles. Of course miles of extensive suburbs lie beyond these points, but these must be looked upon as being in the country and not in the town. We could have lingered long on Mount "Belle Vue," and gazed upon the beautiful panorama which lay before us; but the last rays of an autumnal sun reminded us that it was time to return home. Having completed the circle of the Tycoon's castle, we took a southerly course; and winding our way through streets which sometimes led us over little hills, sometimes through lanes and gardens, we in due time reached the gates of the British Legation.

A Yedo Gentleman, with Servant carrying Sword, and Custom-house Officer with Fan

1 The act of suicide by ripping open the stomach. |