|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

THE NEIGHBOURHOOD

Celebrated places make a strong and often a visual impression upon the mind before they are seen either in reality or in picture. Windsor Castle, especially from the west and at some little distance, is one of those which confirm and even augment, when first seen, the mysterious vision of the imagination. Seen from the flat meadows of Clewer on a moist morning, when thrushes are singing in the elms, Windsor Castle rises up like a cloud in the east, with nothing behind, or on either side of it, but a sky of dull silver, and nothing below but the smoke wreaths of the town gently and separately ascending. It is like a cloud, a huge soft cloud, without motion yet full of change; and it is presently resolved into the predominant Round Tower, and on one side of it the perpendicularly carved St. George's Chapel and the Curfew Tower, on the other side the cliffy, long front of the State Apartments. Even thus clear, the buildings are as remote as a cloud in a mental atmosphere of time and undefined associations. For these green meadows of Clewer belong to to-day. Behind their cheap fences they seem to expect the builder; they are edged by lowly and modern houses which vote Liberal and flutter white linen on the grey air. And on every hand the country is what it has been made within recent times. The river, the Court, and Eton College have changed the face of this countryside into something characteristic in every detail of a piece of England which is both attractive in itself and conveniently near London-almost within half an hour by rail and hardly more by road, if you ignore the law and the multitude. It is dotted with neat white-windowed houses of the rich and comparatively rich. The very dogs are wearing Conservative ribbons as they trot between their slouching red-faced masters and their delicately stepping indolent mistresses. The roads are many and excellent, and the beat of carriage horses' hoofs is a constant music, though interrupted by the motor car's hoot and throb and hiss. Every road is "as smooth as a die, a real stockjobber's road". For centuries the roads to Windsor must have been exceptionally good; in Swift's time it was little more than a three-hours' journey from London. The inns are many. Bread and cheese and a drink cost half a crown, by paying which the visitor confers upon himself a companionship in a nameless but very honourable Victorian or Edwardian Order. There are many other instruments of civilization railway stations, boathouses, Wellington College, the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, the Royal Holloway College for Women, not to speak of the racecourses at Ascot and at Windsor, and the Criminal Lunatic Asylum at Broadmoor, while Aldershot itself is really in the same district.

On one side of the road from Staines to Old Windsor are gasworks, perhaps the most impressive and singular of purely modern architectural monuments; on the other is Runnymede, a vast green level, skirted by the river and walled by woods, perfectly worthy of the scene of King John's humiliation and the Barons' triumph in 1215, which have left it probably as it was before them, except for the hedges of whitethorn. The Workhouse at Old Windsor lies close to some of the most masculine iron oaks, some of the quietest reedy water and furry turf. And if the near neighbourhood of a running river, wide grass, embowered hills, and the great skies over the Thames, cause new things to rasp a little more harshly than usual, these in their turn give an exquisite edge to the rusticity. Nowhere are elmy meadows, mistletoed poplars, willowy serpentining brooks, sweeter than at Datchet: the very name has a country sound before it is seen, and without any magical help from The Merry Wives of Windsor. Nowhere more beautifully does the deer trip half a dozen steps and then rise and glide the same distance with only a forward motion, than under the spruces, at the edge of the high road, within half a mile of the confectionery turrets of Holloway College.

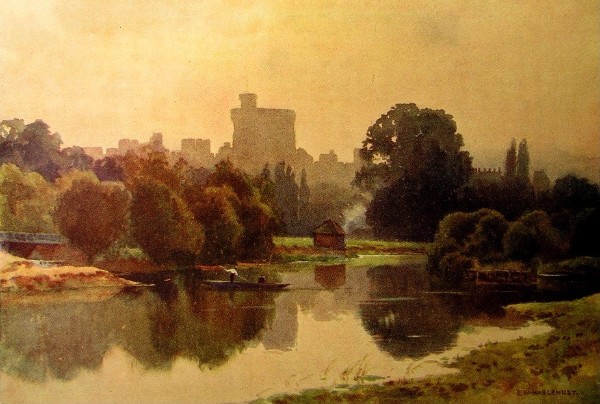

Windsor Castle from Fellow's Eyot, Eton

This tract of country was one of the earliest to be highly civilized, and for three centuries the dilettante has admired it. John Evelyn was at Windsor on June 8, 1654, and found the Castle rooms "melancholy and of ancient magnificence", but walking on the terrace, he thought that "Eton, with the park, meandering Thames, and sweet meadows yield one of the most delightful prospects". Ten years later, Pepys exclaimed: "Lord! the prospect that is in the balcony in the Queen's lodgings, and the terrace and walk, are strange things to consider, being the best in the world, sure". Swift told Stella that Windsor was "a delicious place". Gray stood on the same terrace looking towards Eton, and wrote a poem which began as if it was to be his Ode on the Intimations of Immortality, such was the feeling of its first two verses, and these lines especially:

|

I feel the gales that from ye blow A momentary bliss bestow. |

I forget the rest. Gray had an aunt at Stoke Poges, near Eton, and visited Stoke Park, where in 1799 a Mr. Penn put up a monument to him as author of the Elegy in a Country Churchyard. As famous by name, but far less read, is the "Cooper's Hill", which Sir John Denham wrote in the first year of the Civil War. In the opening lines

|

Sure there are poets who did never dream Upon Parnassus, nor did taste the stream Of Helicon; we therefore may suppose Those made not poets, but the poets those. And as courts make not kings, but kings the court, So where the Muses and their train resort Parnassus stands; if I can be to thee A poet, thou Parnassus art to me |

the feeling and versification foreshadow much later and better work. But few readers can now do more than remember having heard the four lines to the Thames which express the poet's vain aspiration:

|

O could I flow like thee, and make thy stream My great example, as it is my theme! Though deep, yet clear; though gentle, yet not dull; Strong without rage, without o'erflowing full. |

Denham lived on Cooper's Hill, at Ankerwyke Purnish, three miles from Windsor; his contemporary, Edmund Waller, at Hall Barn at Beaconsfield, ten miles away; Milton at Horton and Chalfont; Pope stayed at Binfield, and, sixty years after Denham's poem, wrote his Windsor Forest. With all his asseveration he does nothing to convince us that he was ever at Windsor, or that, if so, he was glad to be there. It is hard to believe that a lover of trees wrote:

|

Let old Arcadia boast her ample plain, Th' immortal huntress, and her virgin train; Nor envy, Windsor! since thy shades have seen As bright a Goddess, and as chaste a Queen; Whose care, like hers, protects the sylvan reign, The Earth's fair light, and Empress of the main. |

He alludes to Queen Anne. The greater part of the poem is in a language no longer intelligible, and it should be remembered it was written at the time when Windsor Park began to be what it now is. I recognize the same familiar strangeness in the style of an anonymous poet who described a stag chase in Windsor Forest in 1739. That Frederick, Prince of Wales, was his theme did not daunt but inspired him, and he says:

|

Round Frederick's Brows their Crowns let Dryads wreath, Hence taught to grasp at Dangers, Wounds, and Death. |

This was a language not only praised by Swift as well as by later critics, but then commonly understood, though there is no proof that it was ever spoken. It is fairly certain that an anonymous poet of 1708 represented some inner truth and vision, now alas! irrecoverable, by the words in his "Windsor Castle":

|

Beneath this Palace flows fair Thames's Streams, Where spreading Elms shade from the Sun's hot Beams; Where beauteous Sea-Nymphs on the Waters sport, And bulky Tritons grace the splendid Court. |

For him Queen Anne was like the sun, and he believed that:

|

Clouds with mourning Sables, deck'd the Skies, Till Anna like another Sun did rise. |

If we take "Queen Anne" as being the equivalent of "Sun", it may still be possible to make out the cipher which he and Pope used so mysteriously.

These are not the only great men connected with Windsor and the neighbourhood in the days of its transformation. Cowley, the eagle Cowley, came to the Porch House at Chertsey for his last years, and died there in 1667. Colley Cibber, the famous Laureate, was drawn into the charmed land at Hill House, White Waltham. Later came Thomson to Richmond. Beaconsfield was the home and burial place of Burke. where Johnson and Mirabeau talked with him. At St. Anne's Hill, near Chertsey, Charles James Fox, that lover of nightingales, lived for five years at the end of his life. It was to Dropmore, and its library and gardens, that Lord Grenville retired for his last twenty years. And at Marlow Shelley moored his boat to write Laon and Cythna; at Bishopsgate he wrote Alastor; but for a romantic poet to come within a few miles of Windsor, even though he was once an Etonian, was a rash if not a sacrilegious act, and it is out of the picture. For this country is the creation of the ages of Denham and Pope and George the Fourth, who probably did not read Shelley. The plantation of the two miles of elms in the Long Walk was begun under Charles II in 1680, and these are far more impressive than the oaks at Swinley, which remind the imaginative of Alfred and the Confessor. The straight lines of this Walk and of Queen Anne's ride dominate the Park. At Cranbourne the significant fact is not that William the Conqueror's Oak is in the White Deer Enclosure, but that the racehorse "Eclipse" was born here in 1764. The Bray Wood oak trees that sprouted in the Middle Ages were suddenly modernized by being named after Queen Anne and Queen Charlotte.

The Lower Ward, Windsor Castle

When Hazlitt went to see the pictures at Windsor, he said: "Pope's lines on Windsor Forest suggest themselves to the mind and make the air about it delicate". It looks a little odd to attribute to such a poem the effect of making the air delicate Banquo having observed to Duncan that where the martlets "most breed and haunt ... the air is delicate". Yet it has a truth. The delicacy is sophisticated; it is the delicacy of three not to say nine-centuries of artifice, or of Nature hand in hand with Sir Christopher Wren, Grinling Gibbons, Antonio Verrio, Alexander Pope, Esquire, and the great gardeners. This artifice is triumphant on the East Terrace of the Castle itself, the smooth walk half a mile long, the orangery, the dark and bright symmetrical Italian garden, with its marble and bronze statuary and its elephants and nymphs, seen from the white-and-gold royal dining-room. It is strong on the smooth sculptured turf below the Round Tower and the rose garden in the ditch, though quaintly alleviated by the gorse above that; still strong in the avenues of great elms in the Home Park, the lime trees, the grass, as smooth as a lake and untrodden save by birds, under the Castle hill and the high rookery trees. If you escape it among the bracken and the warty oaks of the Great Park, it is suddenly upon you with violence when you look up at Snow Hill and see the colossal copper statue of Farmer George on horseback, more magnificent and less amiable now than in life. It is more than perfect it is rampant and even, so far as is consistent with its formality, rollicking at Virginia Water, the largest artificial water in England, completed under George III, with its laced waterfall, its ruined columns brought from Tripoli by George IV, its marble altar dedicated to Jupiter Helios; the dark yews, close by, and the cedars and stone pines of Belvidere Wood; the heronry, and the Fishing Cottage which imperfectly replaces a Fishing Temple in the Chinese style. If Pope's "Windsor Forest" has become obscure in the night of two hundred years, Virginia Water speaks in an unquestionable and still flourishing style.

The Castle itself, that sublime cloud upon the western horizon, if it is approached more nearly, is not what it seems when, from a road or river far to the west, it is fit to embody our fancies of that fairest castle that man ever saw, in the dream of Maxen; or from the fields of Datchet; or from the railway arch over the Clewer footpath, which gives a view of smooth water gleaming between old walls, with swans, placid masts and curled pennons, and to the left Eton Chapel and its high dark windows among poplars and serrated roofs in a sky of grey satin, and to the right the closely gathered huge bulk of the Castle above the small town.

As you walk under the Curfew Tower, the Garter Tower, the Salisbury Tower, in Thames Street, only the mass and outline announce antiquity; the streets, the names over the shops, even the old man who has dyed his white beard to get work as a scaffolder, look more ancient. Doubtless the jackdaws, gliding straight out into the clear air from the Round Tower, have been there since Creηy, but the stonework is new. That also is the work of George IV. Except St. George's Chapel, the timber and herring-boned brick of the Horse-shoe Cloister, and the stone houses of the Military Knights where men obviously live, and the tranquil and leafy Canons' Cloister at the top of the Hundred Steps, most of the exterior of Windsor looks and is new. There is little foliage on the walls, very little moss and green mould, and small space given to the festoons of the bellflower, which contrives its ivy-shaped humid leaves out of the driest stone. The thrush sings with a clear, wild note that seems scarcely earned by the barren hard walls. Even if searched for, ancient buildings are not numerous or easy to find. Part of the lower story eastward from the Devil's Tower, and some foundations, are of Henry II's time. From Henry III's more survives the outer wall on the west and its three towers, the wall of the South Ambulatory in the Dean's Cloister, a door behind the altar of the chapel, the remains of the Domum Regis on the north of the chapel in one of the Canons' houses, and the King's Hall, now a library. The work of Edward III and William of Wykeham gives its form to the Castle as a whole. Of Edward IV's work St. George's Chapel and the Horse-shoe Cloisters remain. St. George's Chapel is the finest and most perfect survival from the Castle as it was at the end of the middle ages. Ruskin called it "a very visible piece of romance". It is exquisite and elaborate. It holds and embalms the sunlight. It might be called hard, and the nave and aisles are at first sight a little cold on account of the lack of history, except for the mildly pathetic monument to George V of Hanover. But the choir, with its pomp of banners, the swords, helmets, mantels, and arms of the Garter Knights, is of an incomparable sombre gorgeousness. The groined vault of the nave of St. George's Chapel, and the Tudor buildings on the north side, and the south and east walls of the Tomb House, are Henry VII's; the groined vault of the choir at St. George's, and the entrance gateway, are Henry VIII's. The gallery and facade, with the postern at the west end of the North Terrace, are Elizabethan.

The Horse-Shoe Cloisters and St. George's Chapel

The furniture and decorations of the Castle are splendid and costly, but not of great age. The collection of pictures is as large but not as well displayed as if it were a public gallery. The tapestries are more suitable to a residence, if less pleasing in themselves; they belong to the last two centuries. Grinling Gibbons' life-like carvings of fish, fowl, and fruit are extraordinarily appropriate here. We miss Lely's portraits of the beauties of the Restoration, which have gone to Hampton Court; for they belong to the last period when the Castle was thoroughly alive, royally and humanly. None of the furniture and household effects mentioned in an inventory of 1547 is left. There is no Elizabethan or true Jacobean work, because the furniture was continually renewed and kept up-to-date in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Nothing has come down from the time of Cromwell's occupation, but much of Charles II's, William and Mary's, Anne's, and George IV's. George IV was also the first considerable collector of ancient arms at Windsor. The armoury is the Prince Consort's. Neither Henry V's "harnois de teste" worn at Agincourt, nor the white armour of Joan of Arc, said to have been sent to Henry VI, is anywhere to be seen.

It was probably the greatest work of George IV, with the help of the architect, Sir Jeffry Wyatville, to make Windsor Castle as young as the Brighton Pavilion. He made it fit for a king of taste to live in. His raw material was not a mediaeval castle slowly accumulated by Angevins, Plantagenets, Lancastrians, Yorkists, and Tudors, but a mediaeval castle which had been iced or Italianized for Charles II by Wren. Edward III had been as sweeping, but he destroyed the old and built the new in the living fashion of his own time. George IV had not the strength or purpose, though he had the money, to do the same. He lived at the beginning of an age that knew so much of other ages, what they did, and how they did it, that it had no trust in itself, seeing itself as but part of a process, and therefore incapable of acting freely and instinctively in that co-operation with past and future which makes a sane and hearty present. If he had lived later in this age, he might have restored Windsor with more knowledge and less temerity. But it is better as it is. Better to have what George IV really liked than what a generation of art critics timidly believes and vociferously asserts to be correct. He has left us a substantial building of roughly mediaeval appearance which might still enable Burke to compare the British Monarchy to "the proud keep of Windsor". It is still national in its magnitude and position, in its history and reputation, as what Michael Drayton called "that supremest seat of the great English kings".

Click the book image to continue to the next chapter