| 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Wild Pastures Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

| 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Wild Pastures Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

|

| “Bug, bug, bug, I've spit on the worms I dug; Bug, bug, give me my wish, A great big string of great big fish.” |

Properly managed this was never known to fail; if it does it is because you have buried one or more of your bugs bottom up.

It is not so easy to catch a lucky bug, however. He is a very modern type of monitor, for his engine power is of the highest, steam is always at the top notch, and he can dart away in a straight line with all the concentrated fury of a torpedo boat. Moreover, he is convertible, and I have seen him when completely surrounded by enemies become a submarine and dive straight for the bottom and stay there. He may have an oxygen tank; anyway, he does n't come up until he gets ready, when he appears fresh and hearty and ready for another waltz.

A fellow surface sailor of his, or rather skipper, is a different type of bug. This is the water-strider, a veritable Cassius of the cove, with the lean and hungry look of an overgrown, underfed mosquito. There is no merry waltz with his fellows about this piratical-looking chap. He spreads his four long legs like a Maltese cross, and the tips of them are all that touch the water. These dent it into minute dimples, but do not penetrate, and his bugship skips energetically about on the four dents, hopping at times like a veritable flea. Sometimes he jumps a half-inch high and skitters along the surface as a boy skips a stone; again he poises, lowers his body till it all but rests on the water, then raises it till he is high on four stilts, and all the time not even his toes are wet.

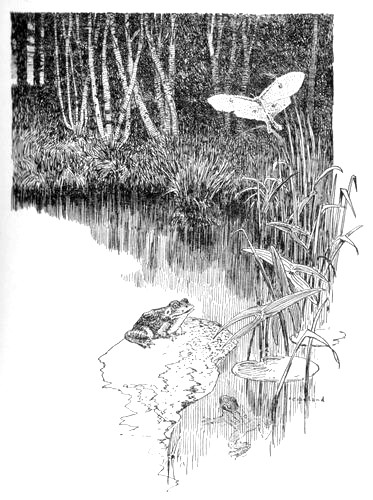

Entering the cove in mid-afternoon you might think the swooning heat had left it no life awake other than the water insects and the dragon-flies that race them in airship fashion above. Yet you have but to ground your canoe on a sedgy shallow, sit motionless, and wait. Nor have you to wait long. There is a breathless pause as if all things waited to see what this leviathan of the outer deep meant to do next; then a voice at your very elbow says reassuringly, “Tu-g-g-g!” That is as near as you can come to it with type. There are no characters that will express its guttural vehemence which strikes you like a blow on the chest; or its sympathetic resonance. Take your violin, drop the G string to a tension so low that it will hardly vibrate musically, then twang it. That suggests the tone. But you know it well enough without description.

Immediately there comes an answering chorus of “tu-g-gs,” here, there, in a score of places all along the shore line and among the island clumps of bushes, prelude of frog talk galore for a moment or two, followed by brief silence. Then, taking advantage of the oratorical pause, an old-timer sets up a tremendously hoarse and vibrant bellow. “A-hr-r-h-h-u-m-mm!” he says, “A-hr-r-h-h-u-m-mm!” with the accent on the rum. You can hear him half a mile, and immediately there is a “chug-squeak-splash” from a little fellow, as if, unable to furnish the beverage at short notice, he became affrighted and without delay decided that a sequestered nook on bottom between two stones was for him. Then the cove goes to sleep again; you can almost hear the silence snore.

Little by little, if you look about you shall see them, some right within reach of your paddle. I never know whether they slip under when the canoe approaches and bob up again noiselessly after all is still, or whether they are there all the time, only so well concealed by nature that the eye does not note them at first; but I do know that you never see them until you have waited a bit. Their brown backs are just under water, their green-brown heads just enough above the surface so that the nostrils will get air; and there they wait, motionless, for hours and hours, for time and tide to serve luncheon. Even with only the tops of their heads visible they make you laugh, for their pop eyes are popped so high above the tops of their flat heads that they make you think of automobile bug lights set well up above the motor hood.

I note a shipwrecked June beetle clinging half drowned to a spear of grass and I toss him over within six inches of a frog. There is a splash, a gulp, and the beetle with his frantically clawing, thorny-toed legs is passed on to kingdom come without a crunch. Once or twice after that this frog stirred as if he had an uneasy conscience, but he seemed to suffer no internal pangs, indeed he winked the circular yellow lining of his eye at me these times as if he enjoyed it. It had all the effects of smacking the lips.

The afternoon dreams down from its pinnacle of hazy heat to the soft level of eventide. Under the pines of the west side of the cove the level sun slips in and seems to caress the green trunks, and the tops above sing a little sighing song of contentment. Strange you have not heard this before, for the wind has been there all the afternoon. But it is toward nightfall that the cove wakes up and you hear many lisping elfin sounds that you have never noticed during the mid-afternoon heat. You hear the sedges talking in the undulations now. You did not hear them before, yet the undulations have been gliding dreamily among the sedges all day.

The pasture birds are waking up their preludes of evensong, and the sun across the cove to the west is glorifying all the quivering canopy of green leaves through which it shines with a luminous, diaphanous quality which makes magic all along that side of the cove.

You are on the borderland between the clear definition of reality and the mystic haze of nightfall. To the west, looking away from the glow, all is gently but clearly defined; to the east, looking into the golden rose of the sunset through the shimmering illusion of leaves, lies the pathway to the land that the king's son saw in the Arabian Night's tale.

The nightly entertainment, the evening minstrel show, is about to begin in the cove, an entertainment in which the frogs are the minstrels, an all star performance, for every one of them is capable of being an end man or interlocutor or soloist as the case may require.

Already the audience is beginning to gather. First comes a gray squirrel scratching down a maple trunk, his strong clawed hind feet digging into the bark and holding him wherever he wishes them to, as if he were an inverted lineman. Suddenly he sights the canoe and its occupant and blows up. Nothing else will express his sudden outpouring of scolding and denunciation of this creature that has usurped a front seat. The sounds burst out of him like the escaping steam from a great mogul engine waiting on a siding for its freight, and he quivers from head to foot, like the engine, with the intensity of the ebullition. Suddenly there is a “quawk!” directly over his head, a single cry shot out from the catarrhal throat of a night heron that is just sailing down. The gray squirrel shoots three feet into the air, lands on another maple, flashes up a birch and goes crashing through the birch tops off into the woods, where you faintly hear him jawing still. The night heron whirls with a great flapping and puts to sea with more quawks of alarm. But these two were not especially wanted at the concert. The night heron particularly is an unlovely bird in appearance, voice, and manner. The skippers and the lucky bugs crowd in together, each among its kind, close to the reedy margin, to be as near the performers as possible, and behold, there come sailing in from sea tiny argosies of dainty people, the loveliest free swimmers of the pond. Golden heads nodding in gracious recognition, they come, slender bodied and graceful, trailing long robes of filmy lace beneath them in the water.

The botanists, who shall be hung some day for their literalness, have named these lovely denizens of the cove bladderworts, or Utricularia, if you wish the Latin form, because they float on their air-inflated leaves and trail their roots beneath them, free in the water, scorning the contaminating touch of earth. The off-shore wind of noon had sailed these out well beyond the mouth of the cove, now the evening breeze is bringing them in again for the concert.

They should have been named after some dainty lady of the old Greek mythology, some fair sailor lass who crossed the wake of Ulysses, perchance, and lingers on placid seas waiting his return to this day, for you will see their golden heads nodding along on the little waves of the cove all summer.

These are the patricians of the concert. There is a great tuning of instruments going on already and a trying out of voices, yet for some reason there is delay. Then. comes the queen herself. The golden shimmer on the eastern shore has faded and dusk dances up from the undergrowth on the west. It is time and out from among the birches she sails gracefully, a veritable queen of the fairies, clad in ostrich plumes and softest of white velvet, with the most beautiful trailing and undulating opera cloak of softest, delicate green, trimmed with brown and white. You may call her a luna moth if you will. The thing which somewhat resembles her, stuck on a pin in your collection, may be that, but this graceful, soaring creature, pulsing and quivering with life, floating through perfumed dusk, is the queen of the fairies -- no less.

Her arrival is a signal for the olio to begin. Then, indeed, you learn the astonishing number and variety of the frog performers within the cove. The basso profundos sing “Ah-r-h-u-m-m” with amazing gusto. Surely that waiter frog has got over his fright and brought it in quantity. “T-u-g-gs” resound all about like the rattle of a drum corps. There are altos whose voices sound like rasping a stick cheerfully on a picket fence, others whose strain hath a dying fall of internal agony outwardly expressed. A lone belated hyla pipes his plaintive soprano, but the tenors are the strongest of all. The tree toad flutes a fluttering, liquid tremolo, and the toad, the common toad, sits on the grassy margin and swells his throat and sings “Wha-a-a-a-” in long-drawn, dreamy cadence.

You may imitate this sound after a fashion if you wish. Purse your lips and say the French “Eu” in a long drawl once or twice, then the next time you do it whistle at the same time. You will have a very tolerable imitation of this dreamy note. It invites to slumber and it is time to paddle home, for the dusk has deepened to darkness and there is little more for you to see in the cove.