|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

Part II - THE SOLITARY WASPS

THE MASONS

THE mason, or mud-building, wasps occupy

themselves as their names imply.

THE mason, or mud-building, wasps occupy

themselves as their names imply.

They are solitary in their habits, and since they do not dwell together in communities, there are no workers among them, only males and females.

The female is unquestionably the head of the family; she does the whole work of nest-building and provisioning, and has everything her own way.

The male seldom appears upon the scene; he is necessary, but on the whole superfluous in the hard work of life, and he dies in the fall, leaving his partner in undisputed possession of the hereditary family estates, to locate her house as she pleases, and to furnish it as suits her.

The “mud-dauber” is the best known of the solitary wasps, as it makes itself at home in our attics and outbuildings, where it constructs the little mud nests so familiar to every one.

It belongs to the division of digger wasps, and

while in a general way these are constructed like the true wasps, they differ in

certain particulars.

It belongs to the division of digger wasps, and

while in a general way these are constructed like the true wasps, they differ in

certain particulars.

Unlike Vespa and Polistes, the eyes of the daubers are not cut across by a semi-lunar line, but are large and projecting; and unlike the true wasps in general, the wings of the mud-dauber, as of all the diggers, are not folded fan-like down the middle.

There are a number of minor characteristics distinguishing the digger from the true wasps, but the wings are the most readily observed, and are enough for ordinary purposes.

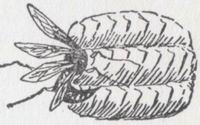

The mud-dauber, or Pelopaeus, is in appearance an elegant dame.

She has a very long and very slender waist, - a ridiculous waist, that long ago caused Aristophanes to compare fashionable women to wasps, calling them what has been translated as “wasp-waisted wenches.”

Pelopaeus' legs are long and slender, and ornamented with spines.

As if conscious of the elegance of their personal appearance, the mud-daubers continually jerk their wings with a self-satisfied little flirt that is as amusing as it is characteristic.

Why should not a wasp as well conditioned as a mud-dauber flirt its wings at the rest of the world ? It should, and it does.

It flirts its wings, but it does not use its sting unless forced to, and it soon becomes tame and friendly with the right kind of people.

Pelopaeus cementarius, very abundant in country places, is a pretty, brown creature with yellow legs.

She may be seen in the summer gathering mud for her nest from the edges of mud-puddles or ponds with muddy banks, or even from the edges of drains; in fact, from almost any place where she can obtain it. She is not at all particular about the quality of her mud, all she asks is mud.

The places she frequents betray her presence by the marks she leaves on the soft earth, for it is spotted all over, where she has chiselled out her little loads.

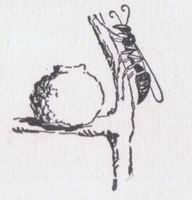

She is a very eager worker when she does work, and when she has found a spot to her mind she falls upon it with vigour, and cuts out a little pellet about as large as a sweet-pea seed with her jaws.

In her earnest devotion to her work she rams her head down under the edge she has loosened, and literally stands on her head while she completes the separation of her pellet.

It is a curious sight to come upon a mud-bank in the summer and find it lined with brown wasps standing on their heads and waving their tails in the air.

The uninitiated observer might imagine this to be some strange wasp-rite, but it is merely Madam Pelopaeus getting a load of mortar with which to build her walls.

Often she spends considerable time running up

and down the bank looking for just the right spot from which to gather her load.

And sometimes she starts to dig it out from several different places, abandoning

them one by one until she finds mud of a consistency quite to her liking.

Occasionally she strikes a large grain of sand or a little pebble, and this

causes her to use what one fears is rather strong wasp language. She flirts her

wings, buzzes vehemently, and flings the obstruction away in a manner that well

expresses her feelings, if wasp gestures mean anything at all.

Often she spends considerable time running up

and down the bank looking for just the right spot from which to gather her load.

And sometimes she starts to dig it out from several different places, abandoning

them one by one until she finds mud of a consistency quite to her liking.

Occasionally she strikes a large grain of sand or a little pebble, and this

causes her to use what one fears is rather strong wasp language. She flirts her

wings, buzzes vehemently, and flings the obstruction away in a manner that well

expresses her feelings, if wasp gestures mean anything at all.

As she works she curls up her precious antennae so that the delicate tips cannot come in contact with the earth.

Sometimes her load is so large that she is obliged to hold it in place by clasping her forelegs about it.

When she has her little ball in her jaws, she flies home.

Her load is so heavy that she is tilted down by

it, her head often being much lower than the rest of her body. Up goes her tail,

down goes her head and she speeds away on hurrying wings, soon lost to sight,

unless her nest happens to be very near the mud upon which she is working.

Her load is so heavy that she is tilted down by

it, her head often being much lower than the rest of her body. Up goes her tail,

down goes her head and she speeds away on hurrying wings, soon lost to sight,

unless her nest happens to be very near the mud upon which she is working.

Mud-daubers once made their nests under the roof of a small shed, coming in and going out through a little window at one end. And here it was discovered that they, too, have their troubles.

The wind was blowing, the window was small, and as the laden wasp neared the opening, the wind caught her and blew her away.

Often she had to try several times before she could make port. When carried past the opening, she made a wide circuit and- sometimes stopped for a moment to rest. Then she put on all steam and headed for the window again.

Once in, she ran up the wall of the shed to her unfinished mud-cradle at the top, and proceeded to apply her load.

She laid the mud down with her jaws, apparently moistening it with a liquid from her mouth, and all the time she was at work she sang merrily.

The mud-dauber always sings at her work.

Her song may be expressive of peace and happiness from a mud-dauber's point of view, but to the unskilled interpretation of man it has rather a sound of intense anxiety, as though she were keyed up to the highest pitch and were venting her feelings in a querulous outcry.

Indeed her voice during the process of nest-building is a shrill, high-keyed buzzing not unlike the sound made by a large fly when caught in a spider's web, and it often leads to her detection when she is building in concealed corners.

One summer, mud-daubers' nests were searched for in vain. They are always common enough -- until one begins to look for them. Because they were wanted that summer -- or for some other reason -- they could not be found.

The wasps themselves were abundant, and were seen constantly at work in a muddy place near the barn pump. But where they took their pellets of mud was another matter. Not a mud-nest was to be found in the barn or in the attic of the house.

There seemed no solution to the mystery until it was one day unexpectedly solved. The voice of a wasp was heard buzzing out its high-keyed song of industry, though no wasp could be seen. At first the tell-tale song was dismissed as the crying of a fly in distress, but when it recurred again and again search was made and the sound traced to one corner of the attic, where at length her ladyship was discovered working for dear life over a rafter, between that and the shingles.

She had found a hole somewhere in the roof, and had chosen this most secret and safe retreat. At least it would have been secret had she kept quiet, and it was safe enough, as it was impossible to get it without unroofing the house. Although the Pelopaeus of to-day has learned to use the roofs provided by man, where there are none handy she finds a dry shelter under a stone or in the stump of a tree, and there makes her mud cradles, this doubtless having been her habit in those long ago times, when wasps existed, but men's houses had not yet covered the earth for the benefit of the little masons. After applying the load of mud in the little shed, Pelopaeus flew out to the roof of another shed, settled on it in the sun, cleaned her face and hands, then settled herself, apparently for a nap.

It was a very short nap, however, for suddenly starting up, she flew quickly to a near mud-hole, worked as if her life depended on it, flew home, and in the same eager, restless way applied her load of mud to the nest. Then she rested on the sunny roof again. She averaged about two loads a minute including her nap.

In order to see her build, it was necessary to stand on a box close to the nest, and with the head of the observer quite close to the roof. When Pelopaeus came in at the window and saw this strange, immense, living object so near her nest, she did not understand it. She flew straight at the face of the intruder, who, as may be supposed, fairly held her breath and steeled her nerves to receive as composedly as possible a deliberate and well-deserved stinging.

But wasps seldom sting if they stop to deliberate, and Pelopaeus certainly was not anxious to imperil her future by stinging unnecessarily, and thereby risking the loss of her sting, which is also her ovipositor, and which is in danger of being left in the wound if she uses it for purposes of discipline.

She poised in front of the intruder's face so close that it was trying, to at least one of the actors in this little drama, to maintain the situation. Not a motion betrayed the fact that Pelopaeus' strange visitor was alive, not a muscle moved, and, perhaps concluding she had mysteriously encountered some sort of mummy or ghost, Pelopaeus went about her business-- and allowed the intruder to remain about hers.

The door to the shed having been 'left open, the wasp when her work was done flew out at the large opening, but she never came in that way. She always appeared at the little window, battling with the wind and holding on to her precious load of mud, although had she gone around to the side of the shed she would have found a much easier entrance.

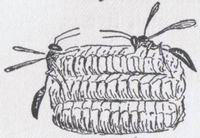

She brought load after load in against the wind

and built the walls of her oblong cells, making each just the right size to

contain a pupa, although the wasp occupant began as a tiny egg, and the mother

wasp had no experience of it in any other form. She built three or four cells

side by side, then above these she piled others, making two or three tiers. Each

little cave had a round opening at one mud end.

She brought load after load in against the wind

and built the walls of her oblong cells, making each just the right size to

contain a pupa, although the wasp occupant began as a tiny egg, and the mother

wasp had no experience of it in any other form. She built three or four cells

side by side, then above these she piled others, making two or three tiers. Each

little cave had a round opening at one mud end.

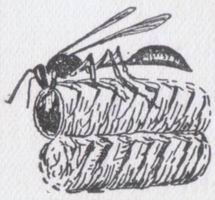

Generally the pile of cells was all plastered over into a shapeless mass before the wasp got through with it, perhaps with a view to strengthening the whole, though sometimes the cells were distinct, as at first made, with pretty braided roofs. For the mud was laid on in strips, first one side and then the other, giving a braided effect to the result.

As soon as a cell was completed, it was stocked with provisions and the opening shut up with a pellet of mud.

The mud-dauber does not give her offspring personal attention. She does not come day after day and put food into ever-open mouths. Being quite alone in her maternal duties, she cannot possibly rear her family and defend them after the manner of the Vespa. She takes care of them, but it is after her own fashion. She catches spiders, and fills the little mud cell full. Upon one of the first caught, she deposits an egg. This is usually attached to the succulent abdomen of the spider, and when the cell is as full as it can be, the end is sealed up, and the egg left to take care of itself.

The mud-dauber cannot store up active spiders,

or the tables might very quickly be turned, and Pelopaeus' tender offspring

become converted into spider, instead of the reverse happening as intended.

The mud-dauber cannot store up active spiders,

or the tables might very quickly be turned, and Pelopaeus' tender offspring

become converted into spider, instead of the reverse happening as intended.

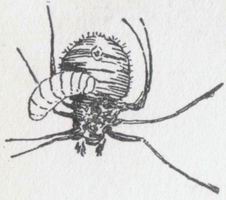

So Pelopaeus catches her spider and stings it. Generally she does not kill it at once, but stings it enough to paralyse it; in which state it remains as fresh food for the larva, though, truth to tell, that ravenous infant does not seem to care much whether its food is alive or not. It devours dead spiders as eagerly as living ones. Mother Pelopaeus has learned the trick of stinging spiders to perfection : grasping her indignant and resentful prey, she thrusts her poisoned dart into its nerve centres so as to quiet it at once. Many people believe the wasps sting the insect used as food on purpose to paralyse, and not to kill it. Since in nearly all nests a part -- and sometimes all -- of the spiders are dead, and since the larvae eat the dead as eagerly as the living, it is probable the stinging is done, primarily, for the purpose of quieting the spiders as soon as possible.

The egg in the mud cell hatches in two or three

days, the larva breakfasts, dines, and sups on abundance of fat spider, and

grows apace.

The egg in the mud cell hatches in two or three

days, the larva breakfasts, dines, and sups on abundance of fat spider, and

grows apace.

When the larva begins its gastronomic operations, it is a little oblong white object without legs, lying in a room tightly packed with luscious spiders. When it ends its gormandising, the cell is still filled, but not now with spider- in the form of spider. The spider has been duly converted into wasp. When, by some chemical and vital action, the tiny white larva has changed into a large fat one that almost fills the cell - all the spiders have been consumed. Not even the legs have been omitted, but all that was spider has been reduced to food by the powerful digestion of the ever-hungry larva.

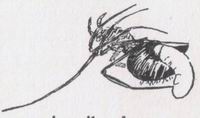

Nothing now remains but a young glutton, which,

having devoured its whole store of provisions, fortunately discovers that it no

longer craves food. It craves rest and a snug retreat. From its lip exudes a

fluid that upon exposure to the air hardens into silk. It moves its head

restlessly; wherever its mouth touches the wall of the cell, a thread of silk is

drawn out. Soon it begins to spin in earnest, and forms a loose lining to its

cell. Then it forms a close, dense covering about its body. At first this

covering is nearly white, but it soon changes to a dark-brown, brittle case,

that looks like the shell of a butterfly chrysalis, excepting that it is very

fragile and almost transparent. Within this shell the marvellous transformation

takes place that changes a white, legless grub into a perfect wasp, with its

complex legs, eyes, antennae, and sting.

Nothing now remains but a young glutton, which,

having devoured its whole store of provisions, fortunately discovers that it no

longer craves food. It craves rest and a snug retreat. From its lip exudes a

fluid that upon exposure to the air hardens into silk. It moves its head

restlessly; wherever its mouth touches the wall of the cell, a thread of silk is

drawn out. Soon it begins to spin in earnest, and forms a loose lining to its

cell. Then it forms a close, dense covering about its body. At first this

covering is nearly white, but it soon changes to a dark-brown, brittle case,

that looks like the shell of a butterfly chrysalis, excepting that it is very

fragile and almost transparent. Within this shell the marvellous transformation

takes place that changes a white, legless grub into a perfect wasp, with its

complex legs, eyes, antennae, and sting.

When the transformation is complete, the wasp bites a hole through the end of its cell, moistening the hard mud with a liquid from its mouth, the delicate pupa skin that covers it is broken off, and it comes forth into the world to see what is next to be learned of life.

There are about an equal number of male and female mud-daubers hatched in a season, and like other wasps, the male mud-daubers have no stings.

Soon after coming from the cell the wasps mate, and the female begins to make mud cells.

If the eggs are laid early in the summer, the wasps hatch out and go to work at once to build nests and lay their eggs. If, however, the egg is laid in the fall, the pupa lies all winter in its cell, not coming forth until the following spring.

The mother wasp dies soon after the eggs are laid, but if she is hatched late in the season and does not lay her eggs, then she crawls into some safe crevice and lies dormant, like the queen Vespa, until spring.

Egg-laying seems to be the culmination of an insect's life, and nearly all of them die as soon as the eggs are laid and the future of their race is thus assured. The wasp is no exception to this general rule; she will live through the winter in order to lay her eggs the following season, but if she lays them she dies at the approach of winter. The queen bee, that lives several years, is one of the few exceptions to the rule. Generally the mud-daubers build new cells for their progeny, but individual wasps differ as much as individuals of any other race of animals; and occasionally one will use an old nest, cleaning out the mud cells and restocking them with provisions, thus saving the labour of carrying mud for a new nest. A number of queens have even been observed working amicably together, clearing out and re-fitting the cells in a large cluster left over from the season before.

In the fall of the year the female mud-daubers often come into the houses and crawl into clothes that may be hanging in a room.

Occasionally some one puts on a garment which contains one or more of these seekers after a cosy winter retreat, when the consequences are more amusing to the onlookers than to the victim.

However, the sting of the mud-daubers dues not amount to much, unless a great many of them are received at once, as in the case of a gentleman who put on a suit of clothes that had been hanging in a closet for a week. All unsuspecting of the dozen wasps that had chosen his garments for their winter home, he went out to dine in state at the house of a friend. He was no sooner seated at the table than the wasps, yielding to the genial warmth of their new surroundings, waked up. One by one they began to avenge the wrong done them, and with perspiration on his brow and anger in his heart, the gentleman was compelled to make a precipitate exit, leaving explanations for a future and more auspicious occasion.

The mud-daubers in the little shed had a good deal of difficulty in finding spiders with which to stock their nests. They preferred a certain plump yellow-and-brown variety which builds a circular web; and upon which they pounced as it sat in the middle of its nest, hoping itself to pounce upon some hapless insect entangled by its silken threads.

The wasp swoops upon the spider like a hawk upon a bird, snatches Arachne away, and plunges a poisoned sting into her vitals before the little spinner knows what has happened. Sometimes Pelopaeus in her extremity darts at an empty web, as if hoping against hope that some toothsome spider might be lurking near.

The mud-daubers sometimes close the end of an empty cell until they are ready to fill it. This is evidently done to keep out trespassers.

A very amusing quarrel was once watched between two mud-daubers that both wanted the same cluster of cells. Whether they had built the cells in common, or whether one had built them and the other had decided it was easier to occupy them than to build some for herself, is unknown.

But at the time they were discovered one was sitting on the nest, evidently waiting to pounce upon the other. Whenever Number Two appeared, Number One would “go for” her, and a lively skirmish would ensue, Number One holding the fort, and going back to sit in triumph on her castle wall, after having chased Number Two away.

As all the cells were closed and no new ones being made, it was not at first apparent what the fuss was about. Presently, however, Number One, having been left in peace for a few moments, began to tap the cells with her antennae, and finally she began to gnaw a hole in the end of one of them. What did it mean? Was she uncapping her rival's cell ? Did she mean to destroy the helpless larva and scatter the enclosed spiders ?

The observer watched with breathless interest until finally a round hole was so neatly made that the cell looked exactly like one that had not yet been capped. And l01 this cell was empty 1 The wasp went in and examined it; evidently finding all as she had left it, she flew off and soon returned with a spider which she deposited in the far end of the cell, after a long struggle with the booty, which was almost too large for the little store-house, and which appeared to have too many and too long legs for the use to which it was being put.

The wasp's own legs and wings were also

superfluities in this particular walk of life, and though she could go

The wasp's own legs and wings were also

superfluities in this particular walk of life, and though she could go

in easily enough, when she struggled out backwards, they seemed on the point of being torn off and left behind with the spider in the cell. One wished she could unhook her members and hang them up outside, though such an arrangement would very likely have resulted in her complete overthrow, as Number Two undoubtedly would have run away with them, and thus have had Number One in her power.

As it was, Number One managed to struggle free with all her parts upon her, and this done she stood on the cell and looked around. Meantime Number Two had hidden behind the mass of, cells, and there she remained until Number One flew away, when she at once appeared and went

and put her head into the open cell as if to see what had been going on there.

She appeared to want to go in and pull that spider out - but it was tucked away at the far end and she probably dared not trust her person in a position of such advantage to a vindictive foe.

Well for her she did not, for while she was

still investigating, along came Number One with a second spider, and away ran

Number Two.

Well for her she did not, for while she was

still investigating, along came Number One with a second spider, and away ran

Number Two.

The spider was crowded into the nest with the same trouble as to superfluous legs and wings on the part of captor and prey as before, then Number One, suspecting Number Two, made chase for her. There was a skirmish, in which the two grappled and rolled head over heels, Number Two finally dropping to the ground, and Number One going for more spiders. Number Two was not out of the combat for good, however. She promptly returned to the nest, went to the back of it, gnawed into a closed cell, triumphantly hauled out a spider and flew off with it. She did not eat it, but flying to a bush near at hand, she dropped it and returned to the nest.

Did the spider so cast out contain the egg of her hated rival? The observer made a faithful search for the discarded spider, but it was impossible to find it in the thick foliage of the bush.

The case was getting serious; the wasps fought constantly, and the one that was carrying spiders was so disturbed that there was little probability of the nest being completed, when the observer came to the rescue. Troublesome Number Two was incarcerated in an insect net, which mishap, no doubt, greatly rejoiced the heart of Number One, who continued her labours zealously; and next morning the cell was found, closed for good, with a cap of mud of much darker colour than that of which the rest of the cell was built.

Mud-daubers' nests are often built of several shades of mud, sometimes one set of cells being curiously patched with light and dark colours. Sometimes the nests are built of sand, held together, perhaps, by a secretion from the wasp's mouth, and once a cluster of nests was found in which four were composed of white plaster, this material the wasps having recognised and appropriated as an admirable material for nest-making.

In the red-clay country of the Carolinas the nests are bright red, and make very pretty decorations to the interiors of the houses; at least, so think some people. Others hold another opinion, and fall upon these red nests and break them to pieces, and try -- in vain -- to remove all traces of their presence.

All the mud nests are very friable and easily broken, so that it is difficult to remove a cluster of them without destroying some. The mud of the nests does not seem to be glued together with secretion from the wasp's mouth, at least not as a rule, but merely dries, and thus keeps its form. It is moulded solidly, so that when dry it is strong enough for the purpose unless it happens to be placed where, through some accident, the rain wets it, in which event it quickly falls to pieces.

In taking down the cells in the little shed the lower tier was broken, and a larva left exposed in one cell, while a pupa in its shell was exposed in another. The anxious mother, returning to finish her last cell and finding the whole fabric gone, with only these luckless infants left and exposed to a merciless world, at once set to work plastering them up again. Evidently feeling that the half-grown larva was a lost wasp anyway, she wasted no time on it, but relentlessly walled it up, or rather floored it over, with not a spider to stay its appetite, and proceeded to build another cell above it.

The pupa, however, she covered over with mud, reproducing its lost cell as well as she could, doubtless feeling that all it needed was to have the cold air kept out, in order to surmount its misfortunes and in time fulfil its, destiny.

When a mud-dauber begins to provision with one species of spider, it continues with the same species, and even selects subjects all of a size as nearly as possible. Thus the inside of the nest presents a very orderly, and were it not for prejudice, appetising appearance.

The mud-wasp's habit of provisioning her cell with insects gave rise to a strange superstition in China, and also in India.

She was seen putting the insect in her nest and sealing it up there, but that she laid an egg on it was not known.

It was consequently believed that she transformed the insect into her own progeny, and as she plastered up the opening, hummed a song over it saying, “Class with me, class with me.” Gradually the transformation took place, until a perfect wasp emerged the following season.

The mud-daubers are easily tamed if taken in time. Once a nest was kept in a room so warm that the first wasp began to gnaw out while the outer world was still under a blanket of snow. When its head began to appear, young Pelopaeus was helped out with a pin. Its antennae were stroked and touched with the finger, and it was given a drop of honey on the tip of the same finger.

Finally Pelopaeus crawled out on the warm hand of her human friend. The warmth was grateful to her and she stayed there as long as allowed. She was transferred to the window, but from time to time fed from her owner's hand and was allowed to creep into the warm palm and stay a little while. She soon learned to come for her meals, and never missed an opportunity to heat her sluggish blood in the palm of her friend. Indeed she did not always wait for an invitation, and it was necessary to keep on guard so as not to close the hand suddenly, thereby, perhaps, squeezing and frightening a live wasp, that might suddenly remember she had a sting to be used when the world went wrong with her, although she did not seem to know she was possessed of a defensive weapon.

But one sad day, the maid, not being acquainted with Pelopaeus, put her out of the window. Meantime another wasp had hatched out unobserved. Pelopaeus' owner, coming in and seeing, as she supposed, her little pet upon the window, picked up the wrong wasp!

Now, though the Pelopaeus is the most gentle of creatures to those she knows, even she could not be expected to submit without preparation to being handled by a fearful great monster that seemed about to destroy her. The new Pelopaeus, frightened out of her wits, no doubt, instantly took the defensive; all the worst attributes of a wasp's nature came to the front. She, an untamed Pelopaeus, had been treated like a tame one, but she did not act in the least like a tame one, and as the friendly hand closed over her irate person - it may be well to draw a curtain over what followed.

Pelopaeus cementarius, though very common, is

not the only common mud- dauber. There is a brilliant blue creature, Pelopaeus

ceruleus, not quite so slender and elegant in form as cementarius, but of such

rich colouring that she makes up in brilliancy what she lacks in form. Her body,

legs, and head are a deep metallic blue, and her wings are also blue, with

lovely purple lights on them.

Pelopaeus cementarius, though very common, is

not the only common mud- dauber. There is a brilliant blue creature, Pelopaeus

ceruleus, not quite so slender and elegant in form as cementarius, but of such

rich colouring that she makes up in brilliancy what she lacks in form. Her body,

legs, and head are a deep metallic blue, and her wings are also blue, with

lovely purple lights on them.

She is fond of finding her way into attics and under roofs, and there making her little mud-nests. In some sections of the country she is even more common than cementarius, and the habits of the two are quite similar.

Indeed, all the mud-daubers live and work like members of one family.

They all require a great deal of water, and they are not at all particular about the purity of their drink. A thirsty cementarius once flew to a paint-box, and alighting in one of the compartments containing a vivid blue paint, there drank deep draughts with evident satisfaction.

One cannot help wondering what might have been the consequences if she had been kept on a diet of different coloured paints. Would she have become brilliantly variegated, as some flowers do when their stems are put into coloured water, or would her life have paid the forfeit of a too free indulgence in bright waters?

There is a black wasp, less often met with than

the common mud-dauber, that builds galleries several inches long.

There is a black wasp, less often met with than

the common mud-dauber, that builds galleries several inches long.

Each gallery is partitioned off into compartments about the size of the mud-dauber's cell. The galleries are placed vertically on the side of a door-post or elsewhere, and the little architect lays out the plan of her house before building it. That the gallery may maintain its proper width and be kept straight, two parallel lines of mud the right distance apart are first laid down and upon these as guides the arch of the tube is built.

This mud gallery is very prettily braided, and is not defaced by being plastered over. Sometimes several galleries are built side by side touching each other. Sometimes the tube is built to its full length before being divided into partitions, and again the partitions are made as her ladyship advances.

When the tube is fairly started, if she does not want to wait for its completion before laying in provisions and depositing eggs, the wasp fills the end of it with spiders, lays her eggs on one of them, builds a thick mud partition, and proceeds to lengthen the tube. As soon as it is long enough she stocks the next compartment, and closes it, and thus continues until she has finished five or six cells.

All the cells, or compartments, are of the same size, and each is just the size to hold a pupa.

The wasp sings loudly as she builds her pretty apartment-houses with their braided roofs.

These nests cannot be removed unbroken, as the surface upon which they rest forms the floor, and as there is no second tier of cells, if the nests are disturbed all of the occupants are exposed to the air, which is fatal to their lives.

The young of these wasps develop and spin their cocoons the same as those of the common mud-daubers.

There is a pretty little creature belonging to

the family of the true wasps, that makes a nest of mud or clay in the form of a

tiny vase, and many a time the dainty piece of pottery has been found on a bush

and wondered over.

There is a pretty little creature belonging to

the family of the true wasps, that makes a nest of mud or clay in the form of a

tiny vase, and many a time the dainty piece of pottery has been found on a bush

and wondered over.

The little vase is stored with insects, an egg is laid on one of them, and the mouth of the jar is sealed. Sometimes a whole row of these pretty pygmy vases are found on one twig, though more often but one is found at a time.

There are a number of small wasps that have most interesting and sometimes troublesome habits, as in the case of that Odynerus that seems specially devoted to plastering up keyholes 1

It provisions the inside of the lock with fresh stung insects, lays its egg, and to make all secure carefully plasters up the keyhole with moist mud that soon dries into a hard mass that resists the entrance of all disturbers, keys included.

One of these wasps once added materially to the interior decoration of a beautiful cabin in the Blue Ridge Mountains. This cabin was finished with pine inside, and there were many screws used, the heads of which were sunk a quarter of an inch in the wood. The place was not used during the summer. Here was opportunity indeed for wasps that preferred to exercise their intelligence rather than their muscles. No hard work for them! They merely provisioned those holes and sealed them up. When the cabin was opened next spring it was found elaborately decorated with round white circles over all the screw-holes.

One Odynerus in this country makes a many-compartmented mud-nest as large as a hen's egg, and attaches it to a bush.

The mud-wasps make a separate cell for each larva, and this great amount of labour is perhaps rendered necessary by the carnivorous character of the young.

It may be true that “birds in their little nests agree,” but it does not follow that wasps in their little nests agree. The probabilities are that these voracious infants, if more than one occupied the same cell, would eat each other up. Not because they were wicked, but because they were very young, and very hungry, and did not know the difference between spider and brother-larva.

Wasp larvae eagerly feed upon each other if the nests are broken and the occupants spilled out, as happens to some around the circular rim, by means of the' lower lip guided by the mandibles.

“The insect placed itself astride over the rim to work, and, on finishing each addition to the structure, took a turn round, patting the sides with its feet, inside and out, before flying off to gather a fresh pellet.

“It worked only in sunny weather, and the previous layer was sometimes not quite dry when the new coating was added.

“The whole structure takes about a week to complete.

“I left the place before the gay little builder had quite finished her task: she did not accompany the canoe, although we moved along the bank of the river very slowly.”

Mr. Bates describes a mud wasp of another genus

but with habits similar to those of the Pelopaeus, and describes also a large

black kind, three fourths of an inch in length, that makes a tremendous fuss

whilst building its cell.

Mr. Bates describes a mud wasp of another genus

but with habits similar to those of the Pelopaeus, and describes also a large

black kind, three fourths of an inch in length, that makes a tremendous fuss

whilst building its cell.

“It often chooses the walls or doors of chambers for this purpose, and when two or three are at work in the same place their loud humming keeps the house in an uproar.”

A little one of this genus “makes a neat little nest shaped like a carafe; building rows of them together in the corners of verandas:”