|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

VESPA'S STING

VESPA'S abdomen is joined to the thorax by a

very slender attachment, though this is not apparent to the casual observer, as

the broad, blunt end of the abdomen usually conceals the slight thread by which

it is held in place, and makes the wasp look like a much stouter and more

substantially built creature than she is. The true form shows best in a dead

Vespa, which is usually curled up.

VESPA'S abdomen is joined to the thorax by a

very slender attachment, though this is not apparent to the casual observer, as

the broad, blunt end of the abdomen usually conceals the slight thread by which

it is held in place, and makes the wasp look like a much stouter and more

substantially built creature than she is. The true form shows best in a dead

Vespa, which is usually curled up.

Moffett says in his quaint way, --

“The body of the Wasp seemeth to be fastened and

tyed together to the midst of the breast, with a certain thin, fine thread or

line, so that by this disjoyned, and not well compacted composition, they seem

very feeble in their loins or rather to have none at all.”

Most of the wasp's organs of digestion are packed away in the abdomen, and here is the capacious stomach. At the tip of the abdomen is the wasp's serviceable weapon which is also, in the queen, the ovipositor or egg-placer.

The wasp, like the bee, carries its sting in its tail, or, as Moffett vividly expresses it, “Their tayle is armed with a long, stiffe and exceeding venomous sting,” and concerning the efficiency of this weapon there is but one opinion. From early ages to the present time the “fiery darts of the wasps” have furnished illustrations of invincible attack; as when Homer, in the Iliad, speaking of the valour of the Greeks, causes one of the enemy to exclaim amazed, --

|

“I did not look to see the men of Greece Stand thus before our might and our strong arms; Yet they, like pliant-bodied wasps or bees, That build their cells beside the rocky way, And quit not their abode, but, waiting there The hunter, combat for their young -- so these, Although but two, withdraw not from the gates, Nor will, till they be slain or seized alive.” |

Virgil speaks of the “fierce hornet” as destroying bees, and Ovid tells how bald Silenus undertook to rob a nest of hornets, supposing they were bees. Out flew the furious insects and sat them down upon his bald pate and stung until he fell down screaming for help. Bacchus appeared upon the scene and mercifully plastered mud upon the wounds, -- the remedy still in vogue, and probably the only one worth trying.

It is well to remember that wasps are always more active and eager to sting in hot weather and when the sun shines. He who wishes to take a wasp's-nest, will fare better to wait for a cold, damp day when the insects are too chilly to be properly resentful.

In the Bible the Lord uses the hornets to help clear a way for the chosen people.

“Moreover, the Lord thy God will send the hornet among them, until they that are left, and hide themselves from thee, be destroyed.”

Again it is written, --

“And I will send hornets before thee, which shall drive out the Hivite, the Canaanite, and the Hittite from before thee.”

And in a brief history of God's benefits to the children of Israel it is narrated, --

“And I sent the hornet before you, which drave them out from before you, even the two kings of the Amorites.”

In “Cruden's Concordance,” in the introduction to the subject of hornets, we read that “A Christian city, being besieged by Sapores, king of Persia, was delivered by hornets; for the elephants and beasts, being stung by them, waxed unruly, and so the whole army fled.”

Not only have armies been dispersed, but cities have been abandoned because of the fierce onset of the hornets. Moffett says, --

“If we will credit AElianus, the Phasilites, in times past, were constrained to forsake their City, for all their defence, munition, and Armour, all through the multitude and cruel fierceness of the Wasps, wherewith they were annoyed.”

So far from blaming them for thus tormenting the Phaselites, Moffett magnanimously and humorously adds, --

“Again, this manifestly proveth that they want not a hearty and fatherly affection, because with more than heroicall courage and invincible fury they set upon all persons, of what degree or quality soever, that dare attempt to lye in wait to hurt or destroy their young breed, no whit at all dreading Neoptolemus, Pyrrhus, Hector, Achilles, or Agamemnon himself, the Captain General of all the whole Grecians, if he were present.”

The following story corroborates Moffet's estimate of the valour of the wasps.

“Eight miles from Grandie the muleteers suddenly called out ‘Marambundas! Marambundas!’ which indicated the approach of wasps. In a moment all the animals, whether loaded or otherwise, lay down on their backs kicking violently; while the blacks and all persons not already attacked, ran away in different directions, all being careful, by a wide sweep, to avoid the swarms of tormentors that came forward like a cloud. I never witnessed a panic so sudden and complete; and really believe that the bursting of a water-spout could hardly have produced more commotion. However, it must be confessed that the alarm was not without good reason, for so severe is the torture inflicted by these pigmy assailants that the bravest travellers are not ashamed to fly the instant they perceive the host approaching, which is of common occurrence in the campos.”

Aristophanes' well-known comedy “The Wasps,” bears testimony to the popular reputation of Vespa.

The comedy is a satire upon the tendency of the time to inordinate lawsuits, and upon the character of the dicasts or jurymen of the period. A dog is tried for stealing a piece of cheese, and the dicasts are habited as wasps.

“Have a care what you do; they're a sharp, angry crew, quick as wasp's-nest, when urchins molest it,” is the significant warning against the horde of dicasts in the second act.

And the chorus informs us at the end, --

And still, they say, in foreign lands, do men

this language hold,

There's nothing like your Attic wasp, so testy

and so bold.”

In modern times there is no lack of stories of

outrages committed by hornets upon inoffensive humankind, though from the

hornet's point of view there no doubt

In modern times there is no lack of stories of

outrages committed by hornets upon inoffensive humankind, though from the

hornet's point of view there no doubt

was sufficient provocation for every attack, notwithstanding AElianus' assertion about the wasps that “by nature they are great fighters, eager, boysterous, and vehemently tempestuous.”

Our hornets are pleasant enough when let alone, but they will not bear an injury with patience, and Moffett is quite right when he says, --

“Whosoever dare be so knack-hardy as to come near their houses or dwelling places, and to offer any violence or hurt to the same, at the noyse of some one of them all the whole swarm rusheth out, being put into an amazed fear, to help their fellow-citizens and do so busily bestir themselves about the ears of their molesters, as that they send them away packing with more than ordinary pace.”

The hornets of Eastern countries are larger than those of our own part of the world, and seem to have a hotter temper, so that travellers in the. East have often been driven from their positions by this small but valiant foe.

Although it may not be true, as was believed in Pliny's time, that three times nine stings will kill a man, yet there is no doubt that a sufficient number of infuriated wasps; attaching themselves to one person, can deprive him of life,. In India, where the wasps are very abundant and very fierce, a party of engineers, while surveying a railroad on the banks of the Jumna, was once attacked by a colony of hornets, when two of the surveyors were stung to death and several others were severely injured.

The hornets of Shahjehanpoor, however, take the prize as conquerors, for they defied the British army, and for one season held possession of government store-houses where sugar was kept.

During their time of occupation no one dared enter the buildings, and when late in the season the hornets yielded, not to man, but to the hand of death that slays all wasps in the fall of the year, it was found they had consumed nearly three thousand pounds of Her Majesty's sugar, leaving piles of cotton bags chewed full of holes and stuffed with the bodies of defunct hornets.

But the hornets of Shahjehanpoor do a service to the British Government which no doubt more than compensates it for the aid they made on those sugar stores, for they act the part of scavengers and keep the vicinity of the butchers' booths clean.

One has to admit that oriental hornets do seem a trifle precipitate, and perhaps even a little ugly in the use of their stings. Dr. King, of Penang, reports of one: “ He is very vicious, and we are all in great fear of him. No later than last Sunday one flew into the Scotch kirk, where one of the merchants was reading the service, plumped down and stung him instantly on the head, and was off again in a moment. The sting drew blood, besides being excessively painful. I was once stung by two of them while riding at a foot's pace by their nest, on the back of the head. The pain was most severe. Tenderness down the neck and in the part remained for more than two weeks afterwards.”

That was too bad, and seems quite inexcusable; still, the hornets doubtless would argue that Dr. King had no business to be riding so close to their nest; and as for the one that behaved so shamefully in the kirk, what proof have we that bad little boys, who had not gone to church, had not been stirring up the hornets, and enraged them to the point of being glad to “sting any human head they could reach?

At least the hornets that drove Lord Clyde's army into the river were excusable, as they were first attacked by the soldiers.

It seems that -- “A picket of Lord Clyde's army were amusing themselves throwing stones at an odd-looking mass of mud and straw hanging on a tree. One marksman, more successful than his comrades, sent a stone with great effect into the centre of the mysterious object, when out flew a cloud of hornets and drove Lord Clyde's invincibles into the rive .”

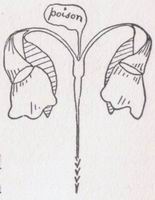

The sting of the wasp is like that of the bee in

structure and action.

It is composed of a sharp-pointed sheath with a lengthwise groove on one side, into which are fitted two barbed lances that play up and down in the groove.

The lances are moved by a system levers composed of flat horny plates connected to the upper end of the sheath and lances and controlled by muscles.

The sheath is also barbed at the end so as to hold the sting in place while the lances are being thrust deeper and deeper into the skin.

A poison-sac communicates with the upper end of the sting, and from the sac the poison is pumped into the wound by the motion of the lances.

The sting of the wasp is very sharp and very small, and it is the poison pumped into the wound rather than the wound itself that causes the unpleasant consequences of a wasp sting. The sting, if unpoisoned, would cause no more pain than the prick of a fine needle.

Usually the wasp, like the bee, loses its sting when it plunges that weapon into an enemy. The barbs that point backwards hold the sting fast, and the effort to pull it out often results in tearing the sting from the wasp's body, and as a consequence of the mutilation, the insect soon dies. The larger hornets are often strong enough to withdraw the sting uninjured, and where this is the case they do not hesitate to use it again and yet again.

Where the sting is left in the wound it should be removed at once, as the muscles that are torn away with it continue to contract and to pump the poison into the wound.

The wasp, like the bee, has two little feelers attached to its sting, and these it first protrudes as though to examine the object before inserting the sting.

Probably these feelers are useful in finding the exact spot in the cell where the egg is to be laid.

Claudius AElianus, a Greek writer of the second century, tells us that the people of his time believed wasps found a dead serpent and with its venom poisoned their stings, just as human barbarians poison their darts by dipping them into some venomous substance.

He also informs us that the wasps sharpen their stings by friction, as we sharpen a knife by rubbing the edge against an oil-stone.

According to AElianus too, the wasp did not always find its sting capable of preserving it from 'harm, for the wily fox out-witted the angry Vespa and ate up its nest. Moffett has thus translated the story in his own picturesque style:

“Reynard the Fox, likewise, who is so full of his wiles and crafty shifting, is reported to be in wait to betray Wasps after this sort. The wily thief thrusteth his bushy tail into the Wasp's nest, there holding it so long until he perceives it to be full of them, then drawing it slily forth, he beateth and smiteth his tail full of wasps against the next stone or tree, never resting so long as he seeth any of them alive; and thus playing his Fox like parts many times together, at last he setteth upon their combs, devouring all that he can finde.”