VI

AN AUTUMN WEEK-END

IT had been as glorious a week-end hike as

ever a

tramper could desire. New ground had been covered, with all that that

means in

the way of mild discovery. For weather there were ideal autumn days of

the

golden sort, with rain considerately withheld until shelter for the

night was

at hand. Hostels of genuine homespun hospitality, refreshingly free

from

lackeyed fashionability, had greeted us nightly. After half a hundred

miles

afoot across the highlands of southern Vermont under such conditions,

and at

the height of autumn's glories, what manner of man could fail to return

elated?

It is not often at this, the best of all

walking

seasons, that holidays so fall as to lengthen a week-end into a young

vacation.

When that happens, the impulse to roam, born of sprightly autumn

weather, is

too strong to be resisted, especially if you have a passion for seeing

new

scenes in our own little New England. According to the map this is a

very tiny

corner of the earth that we live in, but to those who make a practice

of

searching out its attractive spots it soon becomes evident that one

life will

not be sufficient to exhaust the possibilities.

After sampling the walking routes of

northern Vermont

on a brief summer holiday, our thoughts turned naturally to the nearer

southern trails of the same State when the autumn opportunity loomed up

on the

calendar. From the Bennington Section of the Green Mountain Club had

come a

seductive little pamphlet and an accompanying topographic map,

descriptive of

the trails through the near-by hills. With the aid of this suggestive

material

we chose a block of country that scaled up approximately one hundred

and fifty

square miles in extent as our field of operations. The course of the

trail lay

through the very heart of the Green Mountain range, at elevations of

from

fifteen hundred to nearly four thousand feet above sea, up ravines,

across

ridges, through high valleys, over mountains.

We found it on the ground, as it appeared

upon the

map, a region full of rugged beauty that was intensified by the

superbly rich

coloring of the old hardwood forests. It would be a charming walking

region at

any season, but we found it in what must be the time of its supreme

attractiveness — flyless, free from

enervating humidity, and painted to suit the most exacting colorist. If

envy

were a virtue one would cherish it toward the fortunate Bennington folk

who

have this playground lying at their door. Happily the field is not so

far

removed in point of railroad hours as to be beyond the reach of others,

and

envy turns to gratitude that the Green Mountain boys have shown so keen

an

appreciation of their native hills as to develop the tramping

possibilities so

adequately.

Here, then, is one opportunity at least

for that

friend who asked for hints as to weekend walking routes. He had tired

of the

oft-repeated country jaunts that lay within the scope of metropolitan

trolley

lines, and longed for fresh woods and pastures, even if he had to run

after

them a little. There are doubtless others like him that even a hundred

miles

of rail will not discourage, especially if they can be covered

comfortably

while they sleep. To one who objects to being routed from his bed in

the early

hour of dawn, to seize a frugal breakfast at an all-night lunch counter

in

order to catch the millhands' trolley, this plan will scarcely appeal.

However,

tramping trips are not for the sybaritic. It is merely a part of the

game, and

the experience is not bad fun — once in a while.

The first stage of the journey was by

sleeper train

from Boston to North Adams. In that flourishing town people rise

betimes to

begin their work, and even on a holiday morning we found them stirring.

Breakfast and the starting-point of the 5.45 trolley to Bennington were

closely

associated on the main street. An hour later we had crossed the line

into

Vermont, and had engaged an auto.. mobile that already stood

conspicuously for

hire where the car dropped us in front of the hotel in Bennington.

Presumably any one sufficiently interested

to make

this trip, made possible through the activities of the Green Mountain

Club,

would be inclined to join that organization in advance, especially as

that

membership carries with it the use of a tidy and well-equipped camp

that is an

essential element to his creature comfort in the remotest corner of

the woods.

With the key to that retreat secured from its custodian we whirled out

five

miles into the edge of the hills, and the real day began at the timely

hour of

eight, where the Club's Long Trail leaves the head of wheel navigation

in the

depths of Hell Hollow.

Here at slightly more than fifteen hundred

feet above

the sea the map showed us a choice of two routes, and the signboards on

the

ground bore out the map. One follows the main stream to its source and

crosses

a low divide, but our choice was for the other that leads up a side

ravine,

which, though slightly longer, gives more variety, and passes a

viewpoint or

two along the higher ridges. The Club's little pamphlet stated that the

trail

up the ravine is rough, hence we wondered if we had blundered off the

right track

when we found ourselves plodding steadily up on a good wood-road along

the

north bank. But doubts are not allowed to last for long on the Club's

trails,

for the little sheet-iron signs, red-painted hereabouts, with "G.M.C."

lettered in white, or frequently just plain red discs nailed to the

trees, invariably

shine out ahead before any nervousness can begin to assert itself. It

is like

following a string of coral beads that leads on mile after mile along

an

invisible thread.

Two miles up the ravine, and one more

across a

spruce-grown saddle, and the trail emerges upon an old farm clearing at

the top

of Hagar Hill, a rise of twelve hundred feet in three pleasant miles.

To the

south the vista opens toward the rolling hills along the Massachusetts

line,

but it is in the east and north that the chief interest lies, for that

way are

seen the landmarks of the first two days of the excursion. Along the

eastern

side of a wide valley stretches the long ridge of Haystack Mountain,

its

culminating southern summit being almost as high as Chocorua of New

Hampshire's

Sandwich Range.

North, beyond a little dip, rises an

unnamed wooded

height over which our trail is about to lead, and just to the right

stands

Stratton Mountain, our main objective.

Back in the early eighteen hundreds this

ridge, like

many another upland clearing, supported its farming family. Highroads

ran along

the lower crests, as here on Hagar Hill, or followed the high valleys

between

the major ranges. Some are passable for wheels today, but others,

like this,

are safe only for pedestrians.

Another hour of leisurely walking suffices

to cross

the dip where Little Pond lies dimpling among the hills, and up to the

summit

beyond, while another thirty minutes of winding down a steep ravine,

with

glimpses of mysterious blue mountains showing dimly through the trees

ahead,

lands one at a deserted lumber camp in the shadow of Glastonbury

Mountain's

bulk.

A circle of blackened stones and charcoal

intimated

that previous voyagers had here called it half a day, and our own

tea-pail was

soon merrily simmering. To follow an old lumber road, much of it

corduroyed,

through five miles of twistings and turnings, is not exciting, but it

was a

pleasant afternoon's ramble. Like all long roads, this has its

inevitable final

turning where it emerges upon the highroad at the Somerset Bridge over

the

Deerfield River. Our lodging for the night lay behind a neighboring

ridge on

the main East Branch, one mile uphill and two more down the farther

side, all

of it on the road. Here again there had been farms in days gone by, and

not so

long past either, for the houses still stood, though tottering, only

two or

three being occupied. From the hill above the East Branch the final

landmark of

the day appeared, the long dam of the New England Power Company,

spanning the

valley ahead, storing the energy that turns the machinery, drives the

trolleys,

and illumines the nights for people in four States. Here, too, was to

be found

the energizing sleep and food that would carry our self-propelled

machinery

over the hills another day, for in the cheery dam-keeper and his genial

wife

was hospitality personified.

Several things were possible for that

second day's

programme, but approaching rain narrowed our plans to a single course.

It is a

three hours' march due north through the woods to the abandoned sawmill

village

at the head of the valley in which lies the Somerset reservoir. The

ancient

highway that served the one-time little community of farms that lay

along these

slopes ran straight, but the rising waters behind the dam have

submerged a

mile of that, and the trail's forced detours add a brace of miles to

the

distance. It is a pleasantly varied up-and-down route across old

weed-grown

hillside farm clearings that yield views of the near-by mountains, and

through

long lengths of forest aisles. From the upper end of the reservoir,

with its

gaunt dead marginal trees, every lower limb and twig of which fluttered

with

ghostly rags of bleached slime that the receding high spring water had

left adhering,

there is a cut-off trail toward Stratton Mountain via Grout's Pond. For

one

bound to the Club camp in the old mill village that trail would add

perhaps a

mile of distance, though that, indeed, might be sufficiently

compensated for by

its greater attractiveness.

Six miles to the camp by the shortest

route brought

us shelter just as the vigorous southeast rain set in. With fair

weather, and

relieved of packs left to hold the camp, it would be a reasonable

afternoon's

walk thence to the top of Stratton Mountain and return. Although the

distance

is long, ten miles for the round trip, nearly a third of it is on a

good

mountain road, and the balance by an excellent trail that lifts one up

the

sixteen hundred feet of elevation on horse grades. Happy beneath a

tight roof,

the afternoon for us was one of busy housekeeping. Provender the Club

camp

does not afford, but forwarned of this our packs had brought the

makings of

three square meals from home. Likely enough some one may wonder what

constitutes

a liberal larder for one who does not enjoy a weighty pack. Like his

boots, the

tramper's grub-stakes need not be fancy, but must be husky. Be it

known, then,

that with a basis of bacon, rice, and hard bread, powdered pea soup,

raisins,

prunes, sweet chocolate, and tea, many appetizing as well as nourishing

changes

can be rung.

Early on a frosty morning that was

brilliant with a

sharp west wind, we strolled up Stratton Mountain (would that it could

recover

its Indian name of Manicknung) in a couple of hours. The dense timber

on the

summit precludes all outlooks, but the sixty-foot steel tower of the

State

Forest Service effectually remedies that defect. It was tantalizingly

provoking to realize that from that little platform up above a pair of

eyes

could see long ranges in the sparkling air of that morning. But we

straightway

found that the view was not for us, for the ice-coated steel shivered

in the

heavy gusts of the wind. It was enough to climb the slippery ladder

rungs

until the eyes were barely level with the surrounding forest crown, and

to

catch glimpses, through the swaying tops, of Greylock to the south, and

of

Equinox nearer at hand to the northwest. But a little higher and the

Green

Mountain Range to the north, the Adirondacks to the west, and the White

Mountains to the east, would have been in view. All that had to be left

for

some future visit under less boisterous conditions.

From Stratton Mountain summit the main

trail leads

northwest through the forest toward Manchester at the foot of Equinox

Mountain,

a matter of eight or ten miles afoot. For us the plan was to double

back to

camp, with an added five miles saunter westward along the country road

leading

over a five-hundred-foot divide, to the ancient tavern at Kelly Stand

for the night.

Everywhere along the road are further

evidences, in

the shape of farm clearings, of an early attempt to bring civilization

into the

hills. To-day, save for an occasional sporting camp, such as that

which gave

us shelter, and the inn at Kelly Stand, there is not an occupied

habitation of

any kind over a distance of fully fifteen miles. Yet a recently erected

tablet

by the roadside not far from camp, declared that in July, 1840, Daniel

Webster

there addressed "about 15,000 people" at a two days' Whig convention.

Even in that day the lumberman had begun to invade the region, for the

first

mill was erected here on the headwaters of the Deerfield, two years

before

Webster's visit. Meantime not only has the farmer gone, but the big

modern

steam mills, with their attendant villages of hands' houses, have had

their

heyday, and are now, for the most part, falling into squalid ruin. For

nearly a

score of years the forests have been free from the shriek of saw and

whistle.

The slashings have rotted away to nourish the rejected forest veterans

in a

sturdy old age, and a new generation of successors; The bear and the

deer are

in residence once more, and the only man-employing industry is found in

the

annual autumn fern-pickers' camps, where the graceful and fragrant

fronds are

gathered by the million for the florists' markets of the cities.

After a night at Kelly Stand a moderately

early

start will see the tramper home next day in time for a late evening

dinner.

Six miles down the narrow winding canyon of the Roaring Branch

furnishes a

happy climax, which is not bedimmed by the final two miles across the

Arlington

valley to the railroad, and to the motor-bus line that plies south

from Dorset

to Bennington, an hour's run. There the hourly trolley service

connects with

the east-bound expresses at North Adams, and the day and the trip are

done.

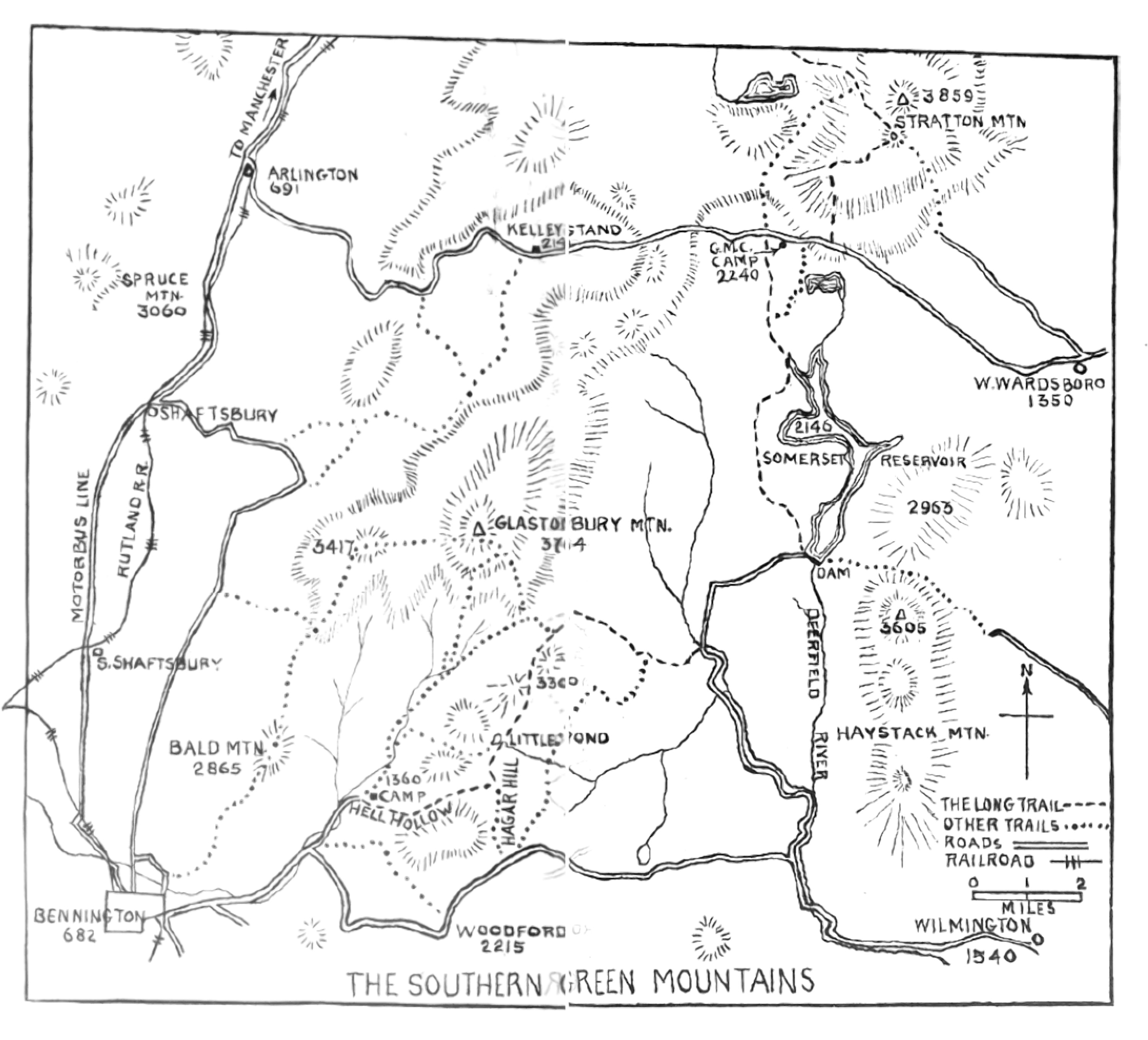

Our path had followed the main Long Trail

as far as

Stratton Mountain summit, but the possibilities of the region are in no

wise

confined to that link in the Club's through-to-Canada route. This is

made

clear by the Green Mountain Club's map of this section, which shows

many an

accessory trail, and other avenues of approach than that through

Bennington. A

branch of the Fitchburg Railroad will land one at Wilmington at the

southern

end of the Haystack Range, while from Wardsboro, on the Central

Vermont, a

stage runs to the western village of that town, which has a trail all

its own

to the top of Stratton. When the Club's proposed extension across the

summits

of the Glastonbury group has been completed, yet another, and perhaps a

more

interesting, line will be open. Especially would this be true if a link

is

furnished from the main summit that will connect with an existing

trail due

north into Kelly Stand. There are also trails to the east and south of

Bennington, as well as north. In short, we had seen but a small sample

of that

attractive playground.

THREE DAYS IN THE SOUTHERN GREEN MOUNTAINS

First Day

* MILES HRS. MIN.

Bennington to Hell Hollow camp,

by auto

5.00

To Hagar Hill clearing

3.00 1

30

To abandoned logging camp, foot

of Glastonbury Mountain. 7.00

3

30

To Somerset Dam.

15.00 7

00

Second Day

Somerset Dam to Hawks' camp 6.00 3

00

To Stratton Mountain summit

40.50 6

00

To Hawks' camp

15.00 8

00

Third Day

Hawks' camp to Arlington (Rutland

Railroad or motor-bus)..

13.00

5

00

* The mileage and elapsed time are

cumulative for

each day, distance and time being figured from point last named in

previous

line. The times here given are sufficient for leisurely walking.

MAP: Topographic trail map published by

Bennington

Section, Green Mountain Club, Bennington, Vt.

|