| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2012 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| IX

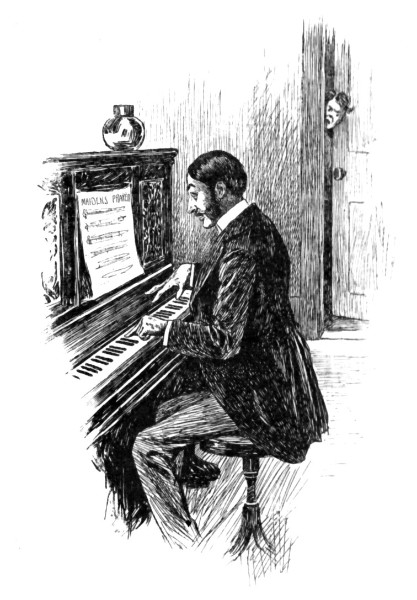

BREAKFAST was very nearly over, and it was of such exceptionally good quality that very few remarks had been made. Finally the ball was set rolling by the Lawyer. "How many packs of cigarettes do you smoke a day?" he asked, as the Idiot took one from his pocket and placed it at the side of his coffee-cup. "Never more than forty-six," said the Idiot. "Why? Do you think of starting a cigarette stand?" "Not at all," said Mr. Brief. "I was only wondering what chance you had to live to maturity, that's all. Your maturity period will be in about eight hundred and sixty years from now, the way I calculate, and it seemed to me that, judging from the number of cigarettes you smoke, you were not likely to last through more than two or three of those years." "Oh, I expect to live longer than that," said the Idiot. "I think I'm good for at least four years. Don't you, Doctor?" "I decline to have anything to say about your case," retorted the Doctor, whose feeling towards the Idiot was not surpassingly affectionate. "In that event I shall probably live five years more," said the Idiot. The Doctor's lip curled, but he remained silent. "You'll live," put in Mr. Pedagog, with a chuckle. "The good die young." "How did you happen to keep alive all this time then, Mr. Pedagog?" asked the Idiot. "I have always eschewed tobacco in every form, for one thing," said Mr. Pedagog. "I am surprised," put in the Idiot. "That's really a bad habit, and I marvel greatly that you should have done it." The School-Master frowned, and looked at the Idiot over the rims of his glasses, as was his wont when he was intent upon getting explanations. "Done what?" he asked, severely. "Chewed tobacco," replied the Idiot. "You just said that one of the things that has kept you lingering in this vale of tears was that you have always chewed tobacco. I never did that, and I never shall do it, because I deem it a detestable diversion." "I didn't say anything of the sort," retorted Mr. Pedagog, getting red in the face. "I never said that I chewed tobacco in any form." "Oh, come!" said the Idiot, with well-feigned impatience, "what's the use of talking that way? We all heard what you said, and I have no doubt that it came as a shock to every member of this assemblage. It certainly was a shock to me, because, with all my weaknesses and bad habits, I think tobacco-chewing unutterably bad. The worst part of it is that you chew it in every form. A man who chews chewing-tobacco only may some time throw off the habit, but when one gets to be such a victim to it that he chews up cigars and cigarettes and plugs of pipe tobacco, it seems to me he is incurable. It is not only a bad habit then; it amounts to a vice." Mr. Pedagog was getting apoplectic. "You know well enough that I never said the words you attribute to me," he said, sternly. "Really, Mr. Pedagog," returned the Idiot, with an irritating shake of his head, as if he were confidentially hinting to the School-Master to keep quiet — "really you pain me by these futile denials. Nobody forced you into the confession. You made it entirely of your own volition. Now I ask you, as a man and brother, what's the use of saying anything more about it? We believe you to be a person of the strictest veracity, but when you say a thing before a tableful of listeners one minute, and deny it the next, we are forced to one of two conclusions, neither of which is pleasing. We must conclude that either, repenting your confession, you sacrifice the truth, or that the habit to which you have confessed has entirely destroyed your perception of the moral question involved. Undue use of tobacco has, I believe, driven men crazy. Opium-eating has destroyed all regard for truth in one whose word had always been regarded as good as a government bond. I presume the undue use of tobacco can accomplish the same sad result. By-the-way, did you ever try opium?" "Opium is ruin," said the Doctor, Mr. Pedagog's indignation being so great that he seemed to be unable to find the words he was evidently desirous of hurling at the Idiot. "It is, indeed," said the Idiot. "I knew a man once who smoked one little pipeful of it, and, while under its influence, sat down at his table and wrote a story of the supernatural order that was so good that everybody said he must have stolen it from Poe or some other master of the weird, and now nobody will have anything to do with him. Tobacco, however, in the sane use of it, is a good thing. I don't know of anything that is more satisfying to the tired man than to lie back on a sofa, of an evening, and puff clouds of smoke and rings into the air. One of the finest dreams I ever had came from smoking. I had blown a great mountain of smoke out into the room, and it seemed to become real, and I climbed to its summit and saw the most beautiful country at my feet — a country in which all men were happy, where there were no troubles of any kind, where no whim was left ungratified, where jealousies were not, and where every man who made more than enough to live on paid the surplus into the common treasury for the use of those who hadn't made quite enough. It was a national realization of the golden rule, and I maintain that if smoking were bad nothing so good, even in the abstract form of an idea, could come out of it." "That's a very nice thought," said the Poet. "I'd like to put that into verse. The idea of a people dividing up their surplus of wealth among the less successful strugglers is beautiful." "You can have it," said the Idiot, with a pleased smile. "I don't write poetry of that kind myself unless I work hard, and I've found that when the poet works hard he produces poems that read hard. You are welcome to it. Another time I was dreaming over my cigar, after a day of the hardest kind of trouble at the office. Everything bad gone wrong with me, and I was blue as indigo. I came home here, lit a cigar, and threw myself down upon my bed and began to puff. I felt like a man in a deep pit, out of which there was no way of getting. I closed my eyes for a second, and to all intents and purposes I lay in that pit. And then what did tobacco do for me? Why, it lifted me right out of my prison. I thought I was sitting on a rock down in the depths. The stars twinkled tantalizingly above me. They invited me to freedom, knowing that freedom was not attainable. Then I blew a ring of smoke from my mouth, and it began to rise slowly at first, and then, catching in a current of air, it flew upward more rapidly, widening constantly, until it disappeared in the darkness above. Then I had a thought. I filled my mouth as full of smoke as possible, and blew forth the greatest ring you ever saw, and as it started to rise I grasped it in my two hands. It struggled beneath my weight, lengthened out into an elliptical link, and broke, and let me down with a dull thud. Then I made two rings, grasping one with my left hand and the other with my right —"  I GRASPED IT IN MY TWO HANDS "And they lifted you out of the pit, I suppose?" sneered the Bibliomaniac. "I do not say that they did," said the Idiot, calmly. "But I do know that when I opened my eyes I wasn't in the pit any longer, but up-stairs in my hall-bedroom." "How awfully mysterious!" said the Doctor, satirically. "Well, I don't approve of smoking," said Mr. Whitechoker. "I agree with the London divine who says it is the pastime of perdition. It is not prompted by natural instincts. It is only the habit of artificial civilization. Dogs and horses and birds get along without it. Why shouldn't man?" "Hear! Hear!" cried Mr. Pedagog, clapping his hands approvingly. "Where? where?" put in the Idiot. "That's a great argument. Dogs don't put up in boarding-houses. Is the boarding-house, therefore, the result of a degraded, artificial civilization? I have seen educated horses that didn't smoke, but I have never seen an educated horse, or an uneducated one, for that matter, that had even had the chance to smoke, or the kind of mouth that would enable him to do it in case he had the chance. I have also observed that horses don't read books, that birds don't eat mutton-chops, that dogs don't go to the opera, that donkeys don't play the piano — at least, four-legged donkeys don't — so you might as well argue that since horses, dogs, birds, and donkeys get along without literature, music, mutton-chops, and piano-playing —" "You've covered music," put in the Lawyer, who liked to be precise. "True; but piano-playing isn't always music," returned the Idiot. "You might as well argue because the beasts and the birds do without these things man ought to. Fish don't smoke, neither do they join the police-force, therefore man should neither smoke nor become a guardian of the peace."  PIANO-PLAYING ISN'T ALWAYS MUSIC "Nevertheless it is a pastime of perdition," insisted Mr. Whitechoker. "No, it isn't," retorted the Idiot. "Smoking is the business of perdition. It smokes because it has to." "There! there!" remonstrated Mr. Pedagog. "You mean hear! hear! I presume," said the Idiot. "I mean that you have said enough!" remarked Mr. Pedagog, sharply. "Very well," said the Idiot. "If I have convinced you all I am satisfied, not to say gratified. But really, Mr. Pedagog," he added, rising to leave the room, "if I were you I'd give up the practice of chewing — " "Hold on a minute, Mr. Idiot," said Mr. Whitechoker, interrupting. He was desirous that Mr. Pedagog should not be further irritated. "Let me ask you one question. Does your old father smoke?" "No," said the Idiot, leaning easily over the back of his chair — "no. What of it?" "Nothing at all — except that perhaps if he could get along without it you might," suggested the clergyman. "He couldn't get along without it if he knew what good tobacco was," said the Idiot. "Then why don't you introduce him to it?" asked the Minister. "Because I do not wish to make him unhappy," returned the Idiot, softly. "He thinks his seventy years have been the happiest years that any mortal ever had, and if now in his seventy-first year he discovered that during the whole period of his manhood he had been deprived through ignorance of so great a blessing as a good cigar, he'd become like the rest of us, living in anticipation of delights to come, and not finding approximate bliss in living over the past. Trust me, my dear Mr. Whitechoker, to look after him. He and my mother and my life are all I have." The Idiot left the room, and Mr. Pedagog put in a greater part of the next half-hour in making personal statements to the remaining boarders to the effect that the word he used was eschewed, and not the one attributed to him by the Idiot. Strange to say, most of them were already aware of that fact. |