| The Golden Fleece. When Jason, the son

of the dethroned King of Iolchos, was a little boy,

he was sent away from his parents, and placed under the queerest

schoolmaster

that ever you heard of. This learned person was one of the people, or

quadrupeds,

called Centaurs. He lived in a cavern, and had the body and legs of a

white

horse, with the head and shoulders of a man. His name was Chiron; and,

in spite

of his odd appearance, he was a very excellent teacher, and had several

scholars, who afterwards did him credit by making a great figure in the

world.

The famous Hercules was one, and so was Achilles, and Philoctetes

likewise, and

Æsculapius, who acquired immense repute as a doctor. The good Chiron

taught his

pupils how to play upon the harp, and how to cure diseases, and how to

use the

sword and shield, together with various other branches of education, in

which

the lads of those days used to be instructed, instead of writing and

arithmetic. I have sometimes

suspected that Master Chiron was not really very

different from other people, but that, being a kind-hearted and merry

old

fellow, he was in the habit of making believe that he was a horse, and

scrambling about the schoolroom on all fours, and letting the little

boys ride

upon his back. And so, when his scholars had grown up, and grown old,

and were

trotting their grandchildren on their knees, they told them about the

sports of

their school days; and these young folks took the idea that their

grandfathers

had been taught their letters by a Centaur, half man and half horse.

Little

children, not quite understanding what is said to them, often get such

absurd

notions into their heads, you know. Be that as it may,

it has always been told for a fact (and always will

be told, as long as the world lasts), that Chiron, with the head of a

schoolmaster, had the body and legs of a horse. Just imagine the grave

old

gentleman clattering and stamping into the schoolroom on his four

hoofs,

perhaps treading on some little fellow's toes, flourishing his switch

tail instead

of a rod, and, now and then, trotting out of doors to eat a mouthful of

grass!

I wonder what the blacksmith charged him for a set of iron shoes? So Jason dwelt in

the cave, with this four-footed Chiron, from the time

that he was an infant, only a few months old, until he had grown to the

full

height of a man. He became a very good harper, I suppose, and skilful

in the

use of weapons, and tolerably acquainted with herbs and other doctor's

stuff,

and, above all, an admirable horseman; for, in teaching young people to

ride,

the good Chiron must have been without a rival among schoolmasters. At

length,

being now a tall and athletic youth, Jason resolved to seek his fortune

in the

world, without asking Chiron's advice, or telling him anything about

the matter.

This was very unwise, to be sure; and I hope none of you, my little

hearers,

will ever follow Jason's example. But, you are to

understand, he had heard how that he himself was a

prince royal, and how his father, King Jason, had been deprived of the

kingdom

of Iolchos by a certain Pelias, who would also have killed Jason, had

he not

been hidden in the Centaur's cave. And, being come to the strength of a

man,

Jason determined to set all this business to rights, and to punish the

wicked

Pelias for wronging his dear father, and to cast him down from the

throne, and

seat himself there instead. With this intention,

he took a spear in each hand, and threw a leopard's

skin over his shoulders, to keep off the rain, and set forth on his

travels,

with his long yellow ringlets waving in the wind. The part of his dress

on

which he most prided himself was a pair of sandals, that had been his

father's.

They were handsomely embroidered, and were tied upon his feet with

strings of

gold. But his whole attire was such as people did not very often see;

and as he

passed along, the women and children ran to the doors and windows,

wondering

whither this beautiful youth was journeying, with his leopard's skin

and his

golden-tied sandals, and what heroic deeds he meant to perform, with a

spear in

his right hand and another in his left. I know not how far

Jason had traveled, when he came to a turbulent

river, which rushed right across his pathway, with specks of white foam

among

its black eddies, hurrying tumultuously onward, and roaring angrily as

it went.

Though not a very broad river in the dry seasons of the year, it was

now

swollen by heavy rains and by the melting of the snow on the sides of

Mount

Olympus; and it thundered so loudly, and looked so wild and dangerous,

that

Jason, bold as he was, thought it prudent to pause upon the brink. The

bed of

the stream seemed to be strewn with sharp and rugged rocks, some of

which

thrust themselves above the water. By and by, an uprooted tree, with

shattered

branches, came drifting along the current, and got entangled among the

rocks.

Now and then, a drowned sheep, and once the carcass of a cow, floated

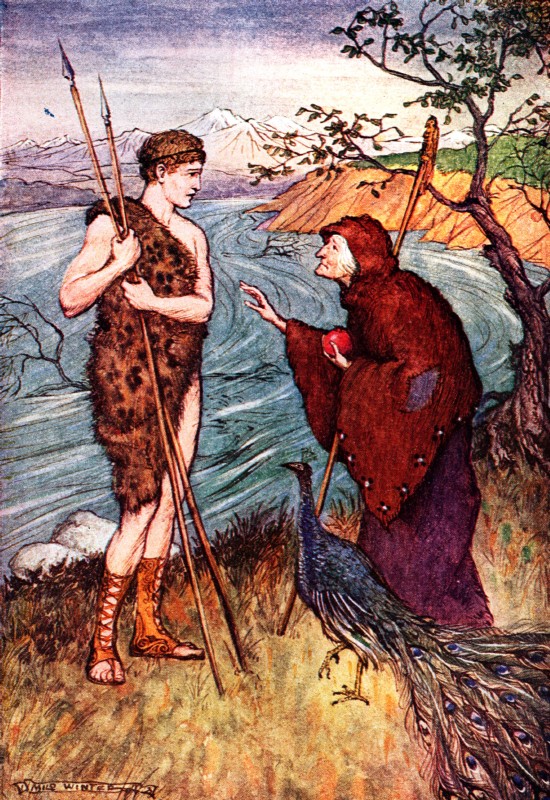

past. In short, the swollen river had already done a great deal of mischief. It was evidently too deep for Jason to wade, and too boisterous for him to swim; he could see no bridge; and as for a boat, had there been any, the rocks would have broken it to pieces in an instant.  "I am going to

Iolchos," answered the young man

"See the poor lad,"

said a cracked voice close to his side.

"He must have had but a poor education, since he does not know how to

cross a little stream like this. Or is he afraid of wetting his fine

golden-stringed sandals? It is a pity his four-footed schoolmaster is

not here

to carry him safely across on his back!" Jason looked round

greatly surprised, for he did not know that anybody

was near. But beside him stood an old woman, with a ragged mantle over

her

head, leaning on a staff, the top of which was carved into the shape of

a

cuckoo. She looked very aged, and wrinkled, and infirm; and yet her

eyes, which

were as brown as those of an ox, were so extremely large and beautiful,

that,

when they were fixed on Jason's eyes, he could see nothing else but

them. The

old woman had a pomegranate in her hand, although the fruit was then

quite out

of season. "Whither are you

going, Jason?" she now asked. She seemed to know

his name, you will observe; and, indeed, those great

brown eyes looked as if they had a knowledge of everything, whether

past or to

come. While Jason was gazing at her, a peacock strutted forward, and

took his

stand at the old woman's side. "I am going to

Iolchos," answered the young man, "to bid

the wicked King Pelias come down from my father's throne, and let me

reign in

his stead." "Ah, well, then,"

said the old woman, still with the same

cracked voice, "if that is all your business, you need not be in a very

great hurry. Just take me on your back, there's a good youth, and carry

me

across the river. I and my peacock have something to do on the other

side, as

well as yourself." "Good mother,"

replied Jason, "your business can hardly

be so important as the pulling down a king from his throne. Besides, as

you may

see for yourself, the river is very boisterous; and if I should chance

to

stumble, it would sweep both of us away more easily than it has carried

off

yonder uprooted tree. I would gladly help you if I could; but I doubt

whether I

am strong enough to carry you across." "Then," said she,

very scornfully, "neither are you

strong enough to pull King Pelias off his throne. And, Jason, unless

you will

help an old woman at her need, you ought not to be a king. What are

kings made

for, save to succor the feeble and distressed? But do as you please.

Either

take me on your back, or with my poor old limbs I shall try my best to

struggle

across the stream." Saying this, the old

woman poked with her staff in the river, as if to

find the safest place in its rocky bed where she might make the first

step. But

Jason, by this time, had grown ashamed of his reluctance to help her.

He felt

that he could never forgive himself, if this poor feeble creature

should come

to any harm in attempting to wrestle against the headlong current. The

good

Chiron, whether half horse or no, had taught him that the noblest use

of his

strength was to assist the weak; and also that he must treat every

young woman

as if she were his sister, and every old one like a mother. Remembering

these

maxims, the vigorous and beautiful young man knelt down, and requested

the good

dame to mount upon his back. "The passage seems

to me not very safe," he remarked.

"But as your business is so urgent, I will try to carry you across. If

the

river sweeps you away, it shall take me too." "That, no doubt,

will be a great comfort to both of us," quoth

the old woman. "But never fear. We shall get safely across." So she threw her

arms around Jason's neck; and lifting her from the

ground, he stepped boldly into the raging and foaming current, and

began to

stagger away from the shore. As for the peacock, it alighted on the old

dame's

shoulder. Jason's two spears, one in each hand, kept him from

stumbling, and

enabled him to feel his way among the hidden rocks; although every

instant, he

expected that his companion and himself would go down the stream,

together with

the driftwood of shattered trees, and the carcasses of the sheep and

cow. Down

came the cold, snowy torrent from the steep side of Olympus, raging and

thundering as if it had a real spite against Jason, or, at all events,

were

determined to snatch off his living burden from his shoulders. When he

was half

way across, the uprooted tree (which I have already told you about)

broke loose

from among the rocks, and bore down upon him, with all its splintered

branches

sticking out like the hundred arms of the giant Briareus. It rushed

past,

however, without touching him. But the next moment his foot was caught

in a

crevice between two rocks, and stuck there so fast, that, in the effort

to get

free, he lost one of his golden-stringed sandals. At this accident

Jason could not help uttering a cry of vexation. "What is the matter,

Jason?" asked the old woman. "Matter enough,"

said the young man. "I have lost a

sandal here among the rocks. And what sort of a figure shall I cut, at

the

court of King Pelias, with a golden-stringed sandal on one foot, and

the other

foot bare!" "Do not take it to

heart," answered his companion cheerily.

"You never met with better fortune than in losing that sandal. It

satisfies me that you are the very person whom the Speaking Oak has

been

talking about." There was no time,

just then, to inquire what the Speaking Oak had said.

But the briskness of her tone encouraged the young man; and, besides,

he had

never in his life felt so vigorous and mighty as since taking this old

woman on

his back. Instead of being exhausted, he gathered strength as he went

on; and,

struggling up against the torrent, he at last gained the opposite

shore,

clambered up the bank, and set down the old dame and her peacock safely

on the

grass. As soon as this was done, however, he could not help looking

rather despondently

at his bare foot, with only a remnant of the golden string of the

sandal

clinging round his ankle. "You will get a

handsomer pair of sandals by and by," said the

old woman, with a kindly look out of her beautiful brown eyes. "Only

let

King Pelias get a glimpse of that bare foot, and you shall see him turn

as pale

as ashes, I promise you. There is your path. Go along, my good Jason,

and my

blessing go with you. And when you sit on your throne remember the old

woman

whom you helped over the river." With these words,

she hobbled away, giving him a smile over her shoulder

as she departed. Whether the light of

her beautiful brown eyes threw a glory round about

her, or whatever the cause might be, Jason fancied that there was

something

very noble and majestic in her figure, after all, and that, though her

gait

seemed to be a rheumatic hobble, yet she moved with as much grace and

dignity

as any queen on earth. Her peacock, which had now fluttered down from

her

shoulder, strutted behind her in a prodigious pomp, and spread out its

magnificent tail on purpose for Jason to admire it. When the old dame

and her peacock were out of sight, Jason set forward

on his journey. After traveling a pretty long distance, he came to a

town

situated at the foot of a mountain, and not a great way from the shore

of the

sea. On the outside of the town there was an immense crowd of people,

not only

men and women, but children too, all in their best clothes, and

evidently

enjoying a holiday. The crowd was thickest towards the sea-shore; and

in that

direction, over the people's heads, Jason saw a wreath of smoke curling

upward

to the blue sky. He inquired of one of the multitude what town it was

near by,

and why so many persons were here assembled together. "This is the kingdom

of Iolchos," answered the man, "and

we are the subjects of King Pelias. Our monarch has summoned us

together, that

we may see him sacrifice a black bull to Neptune, who, they say, is his

majesty's father. Yonder is the king, where you see the smoke going up

from the

altar." While the man spoke

he eyed Jason with great curiosity; for his garb was

quite unlike that of the Iolchians, and it looked very odd to see a

youth with

a leopard's skin over his shoulders, and each hand grasping a spear.

Jason

perceived, too, that the man stared particularly at his feet, one of

which, you

remember, was bare, while the other was decorated with his father's

golden-stringed sandal. "Look at him! only

look at him!" said the man to his next

neighbor. "Do you see? He wears but one sandal!" Upon this, first one

person, and then another, began to stare at Jason,

and everybody seemed to be greatly struck with something in his aspect;

though

they turned their eyes much oftener towards his feet than to any other

part of

his figure. Besides, he could hear them whispering to one another. "One sandal! One

sandal!" they kept saying. "The man with

one sandal! Here he is at last! Whence has he come? What does he mean

to do?

What will the king say to the one-sandaled man?" Poor Jason was

greatly abashed, and made up his mind that the people of

Iolchos were exceedingly ill-bred, to take such public notice of an

accidental

deficiency in his dress. Meanwhile, whether it were that they hustled

him

forward, or that Jason, of his own accord, thrust a passage through the

crowd,

it so happened that he soon found himself close to the smoking altar,

where

King Pelias was sacrificing the black bull. The murmur and hum of the

multitude, in their surprise at the spectacle of Jason with his one

bare foot,

grew so loud that it disturbed the ceremonies; and the king, holding

the great

knife with which he was just going to cut the bull's throat, turned

angrily

about, and fixed his eyes on Jason. The people had now withdrawn from

around

him, so that the youth stood in an open space, near the smoking altar,

front to

front with the angry King Pelias. "Who are you?" cried

the king, with a terrible frown.

"And how dare you make this disturbance, while I am sacrificing a black

bull to my father Neptune?" "It is no fault of

mine," answered Jason. "Your majesty

must blame the rudeness of your subjects, who have raised all this

tumult

because one of my feet happens to be bare." When Jason said

this, the king gave a quick startled glance down at his

feet. "Ha!" muttered he,

"here is the one-sandaled fellow, sure

enough! What can I do with him?" And he clutched more

closely the great knife in his hand, as if he were

half a mind to slay Jason, instead of the black bull. The people round

about

caught up the king's words, indistinctly as they were uttered; and

first there

was a murmur amongst them, and then a loud shout. "The one-sandaled

man has come! The prophecy must be

fulfilled!" For you are to know,

that, many years before, King Pelias had been told

by the Speaking Oak of Dodona, that a man with one sandal should cast

him down

from his throne. On this account, he had given strict orders that

nobody should

ever come into his presence, unless both sandals were securely tied

upon his

feet; and he kept an officer in his palace, whose sole business it was

to

examine people's sandals, and to supply them with a new pair, at the

expense of

the royal treasury, as soon as the old ones began to wear out. In the

whole

course of the king's reign, he had never been thrown into such a fright

and

agitation as by the spectacle of poor Jason's bare foot. But, as he was

naturally a bold and hard-hearted man, he soon took courage, and began

to

consider in what way he might rid himself of this terrible one-sandaled

stranger. "My good young man,"

said King Pelias, taking the softest tone

imaginable, in order to throw Jason off his guard, "you are excessively

welcome to my kingdom. Judging by your dress, you must have traveled a

long

distance, for it is not the fashion to wear leopard skins in this part

of the

world. Pray what may I call your name? and where did you receive your

education?" "My name is Jason,"

answered the young stranger. "Ever

since my infancy, I have dwelt in the cave of Chiron the Centaur. He

was my

instructor, and taught me music, and horsemanship, and how to cure

wounds, and

likewise how to inflict wounds with my weapons!" "I have heard of

Chiron the schoolmaster," replied King

Pelias, "and how that there is an immense deal of learning and wisdom

in

his head, although it happens to be set on a horse's body. It gives me

great

delight to see one of his scholars at my court. But to test how much

you have

profited under so excellent a teacher, will you allow me to ask you a

single

question?" "I do not pretend to

be very wise," said Jason. "But ask

me what you please, and I will answer to the best of my ability." Now King Pelias

meant cunningly to entrap the young man, and to make him

say something that should be the cause of mischief and distraction to

himself.

So, with a crafty and evil smile upon his face, he spoke as follows: "What would you do,

brave Jason," asked he, "if there

were a man in the world, by whom, as you had reason to believe, you

were doomed

to be ruined and slain — what would you do, I say, if that man stood

before

you, and in your power?" When Jason saw the

malice and wickedness which King Pelias could not

prevent from gleaming out of his eyes, he probably guessed that the

king had

discovered what he came for, and that he intended to turn his own words

against

himself. Still he scorned to tell a falsehood. Like an upright and

honorable

prince as he was, he determined to speak out the real truth. Since the

king had

chosen to ask him the question, and since Jason had promised him an

answer,

there was no right way save to tell him precisely what would be the

most

prudent thing to do, if he had his worst enemy in his power. Therefore, after a

moment's consideration, he spoke up, with a firm and

manly voice. "I would send such a

man," said he, "in quest of the

Golden Fleece!" This enterprise, you

will understand, was, of all others, the most

difficult and dangerous in the world. In the first place it would be

necessary

to make a long voyage through unknown seas. There was hardly a hope, or

a

possibility, that any young man who should undertake this voyage would

either

succeed in obtaining the Golden Fleece, or would survive to return

home, and

tell of the perils he had run. The eyes of King Pelias sparkled with

joy,

therefore, when he heard Jason's reply. "Well said, wise man

with the one sandal!" cried he. "Go,

then, and at the peril of your life, bring me back the Golden Fleece." "I go," answered

Jason, composedly. "If I fail, you need

not fear that I will ever come back to trouble you again. But if I

return to

Iolchos with the prize, then, King Pelias, you must hasten down from

your lofty

throne, and give me your crown and sceptre." "That I will," said

the king, with a sneer. "Meantime, I

will keep them very safely for you." The first thing that

Jason thought of doing, after he left the king's

presence, was to go to Dodona, and inquire of the Talking Oak what

course it

was best to pursue. This wonderful tree stood in the center of an

ancient wood.

Its stately trunk rose up a hundred feet into the air, and threw a

broad and

dense shadow over more than an acre of ground. Standing beneath it,

Jason

looked up among the knotted branches and green leaves, and into the

mysterious

heart of the old tree, and spoke aloud, as if he were addressing some

person

who was hidden in the depths of the foliage. "What shall I do,"

said he, "in order to win the Golden

Fleece?" At first there was a

deep silence, not only within the shadow of the

Talking Oak, but all through the solitary wood. In a moment or two,

however,

the leaves of the oak began to stir and rustle, as if a gentle breeze

were

wandering amongst them, although the other trees of the wood were

perfectly

still. The sound grew louder, and became like the roar of a high wind.

By and

by, Jason imagined that he could distinguish words, but very

confusedly,

because each separate leaf of the tree seemed to be a tongue, and the

whole

myriad of tongues were babbling at once. But the noise waxed broader

and

deeper, until it resembled a tornado sweeping through the oak, and

making one

great utterance out of the thousand and thousand of little murmurs

which each

leafy tongue had caused by its rustling. And now, though it still had

the tone

of a mighty wind roaring among the branches, it was also like a deep

bass voice,

speaking as distinctly as a tree could be expected to speak, the

following

words: "Go to Argus, the

shipbuilder, and bid him build a galley with

fifty oars." Then the voice

melted again into the indistinct murmur of the rustling

leaves, and died gradually away. When it was quite gone, Jason felt

inclined to

doubt whether he had actually heard the words, or whether his fancy had

not

shaped them out of the ordinary sound made by a breeze, while passing

through

the thick foliage of the tree. But on inquiry among

the people of Iolchos, he found that there was

really a man in the city, by the name of Argus, who was a very skilful

builder

of vessels. This showed some intelligence in the oak; else how should

it have

known that any such person existed? At Jason's request, Argus readily

consented

to build him a galley so big that it should require fifty strong men to

row it;

although no vessel of such a size and burden had heretofore been seen

in the

world. So the head carpenter and all his journeymen and apprentices

began their

work; and for a good while afterwards, there they were, busily

employed, hewing

out the timbers, and making a great clatter with their hammers; until

the new

ship, which was called the Argo, seemed to be quite ready for sea. And,

as the

Talking Oak had already given him such good advice, Jason thought that

it would

not be amiss to ask for a little more. He visited it again, therefore,

and

standing beside its huge, rough trunk, inquired what he should do next.

This time, there was

no such universal quivering of the leaves,

throughout the whole tree, as there had been before. But after a while,

Jason

observed that the foliage of a great branch which stretched above his

head had

begun to rustle, as if the wind were stirring that one bough, while all

the

other boughs of the oak were at rest. "Cut me off!" said

the branch, as soon as it could speak

distinctly; "cut me off! cut me off! and carve me into a figure-head

for

your galley." Accordingly, Jason

took the branch at its word, and lopped it off the

tree. A carver in the neighborhood engaged to make the figurehead. He

was a

tolerably good workman, and had already carved several figure-heads, in

what he

intended for feminine shapes, and looking pretty much like those which

we see

nowadays stuck up under a vessel's bowsprit, with great staring eyes,

that

never wink at the dash of the spray. But (what was very strange) the

carver

found that his hand was guided by some unseen power, and by a skill

beyond his

own, and that his tools shaped out an image which he had never dreamed

of. When

the work was finished, it turned out to be the figure of a beautiful

woman,

with a helmet on her head, from beneath which the long ringlets fell

down upon

her shoulders. On the left arm was a shield, and in its center appeared

a

lifelike representation of the head of Medusa with the snaky locks. The

right

arm was extended, as if pointing onward. The face of this wonderful

statue,

though not angry or forbidding, was so grave and majestic, that perhaps

you

might call it severe; and as for the mouth, it seemed just ready to

unclose its

lips, and utter words of the deepest wisdom. Jason was delighted

with the oaken image, and gave the carver no rest

until it was completed, and set up where a figure-head has always

stood, from

that time to this, in the vessel's prow. "And now," cried he,

as he stood gazing at the calm, majestic

face of the statue, "I must go to the Talking Oak and inquire what next

to

do." "There is no need of

that, Jason," said a voice which, though

it was far lower, reminded him of the mighty tones of the great oak.

"When

you desire good advice, you can seek it of me." Jason had been

looking straight into the face of the image when these

words were spoken. But he could hardly believe either his ears or his

eyes. The

truth was, however, that the oaken lips had moved, and, to all

appearance, the

voice had proceeded from the statue's mouth. Recovering a little from

his

surprise, Jason bethought himself that the image had been carved out of

the

wood of the Talking Oak, and that, therefore, it was really no great

wonder,

but on the contrary, the most natural thing in the world, that it

should

possess the faculty of speech. It would have been very odd, indeed, if

it had

not. But certainly it was a great piece of good fortune that he should

be able

to carry so wise a block of wood along with him in his perilous voyage.

"Tell me, wondrous

image," exclaimed Jason, — "since you

inherit the wisdom of the Speaking Oak of Dodona, whose daughter you

are, — tell

me, where shall I find fifty bold youths, who will take each of them an

oar of

my galley? They must have sturdy arms to row, and brave hearts to

encounter

perils, or we shall never win the Golden Fleece." "Go," replied the

oaken image, "go, summon all the heroes

of Greece." And, in fact,

considering what a great deed was to be done, could any

advice be wiser than this which Jason received from the figure-head of

his

vessel? He lost no time in sending messengers to all the cities, and

making

known to the whole people of Greece, that Prince Jason, the son of King

Jason,

was going in quest of the Fleece of Gold, and that he desired the help

of

forty-nine of the bravest and strongest young men alive, to row his

vessel and

share his dangers. And Jason himself would be the fiftieth. At this news, the

adventurous youths, all over the country, began to

bestir themselves. Some of them had already fought with giants, and

slain

dragons; and the younger ones, who had not yet met with such good

fortune,

thought it a shame to have lived so long without getting astride of a

flying

serpent, or sticking their spears into a Chimæra, or, at least,

thrusting their

right arms down a monstrous lion's throat. There was a fair prospect

that they

would meet with plenty of such adventures before finding the Golden

Fleece. As

soon as they could furbish up their helmets and shields, therefore, and

gird on

their trusty swords, they came thronging to Iolchos, and clambered on

board the

new galley. Shaking hands with Jason, they assured him that they did

not care a

pin for their lives, but would help row the vessel to the remotest edge

of the

world, and as much farther as he might think it best to go. Many of these brave

fellows had been educated by Chiron, the four-footed

pedagogue, and were therefore old schoolmates of Jason, and knew him to

be a

lad of spirit. The mighty Hercules, whose shoulders afterwards upheld

the sky,

was one of them. And there were Castor and Pollux, the twin brothers,

who were

never accused of being chicken-hearted, although they had been hatched

out of

an egg; and Theseus, who was so renowned for killing the Minotaur, and

Lynceus,

with his wonderfully sharp eyes, which could see through a millstone,

or look

right down into the depths of the earth, and discover the treasures

that were

there; and Orpheus, the very best of harpers, who sang and played upon

his lyre

so sweetly, that the brute beasts stood upon their hind legs, and

capered

merrily to the music. Yes, and at some of his more moving tunes, the

rocks

bestirred their moss-grown bulk out of the ground, and a grove of

forest trees

uprooted themselves, and, nodding their tops to one another, performed

a

country dance. One of the rowers

was a beautiful young woman, named Atalanta, who had

been nursed among the mountains by a bear. So light of foot was this

fair

damsel, that she could step from one foamy crest of a wave to the foamy

crest

of another, without wetting more than the sole of her sandal. She had

grown up

in a very wild way, and talked much about the rights of women, and

loved

hunting and war far better than her needle. But in my opinion, the most

remarkable of this famous company were two sons of the North Wind (airy

youngsters, and of rather a blustering disposition) who had wings on

their

shoulders, and, in case of a calm, could puff out their cheeks, and

blow almost

as fresh a breeze as their father. I ought not to forget the prophets

and

conjurors, of whom there were several in the crew, and who could

foretell what

would happen to-morrow or the next day, or a hundred years hence, but

were

generally quite unconscious of what was passing at the moment. Jason appointed

Tiphys to be helmsman because he was a star-gazer, and

knew the points of the compass. Lynceus, on account of his sharp sight,

was

stationed as a look-out in the prow, where he saw a whole day's sail

ahead, but

was rather apt to overlook things that lay directly under his nose. If

the sea

only happened to be deep enough, however, Lynceus could tell you

exactly what

kind of rocks or sands were at the bottom of it; and he often cried out

to his

companions, that they were sailing over heaps of sunken treasure, which

yet he

was none the richer for beholding. To confess the truth, few people

believed

him when he said it. Well! But when the

Argonauts, as these fifty brave adventurers were

called, had prepared everything for the voyage, an unforeseen

difficulty

threatened to end it before it was begun. The vessel, you must

understand, was

so long, and broad, and ponderous, that the united force of all the

fifty was

insufficient to shove her into the water. Hercules, I suppose, had not

grown to

his full strength, else he might have set her afloat as easily as a

little boy

launches his boat upon a puddle. But here were these fifty heroes,

pushing, and

straining, and growing red in the face, without making the Argo start

an inch.

At last, quite wearied out, they sat themselves down on the shore

exceedingly

disconsolate, and thinking that the vessel must be left to rot and fall

in

pieces, and that they must either swim across the sea or lose the

Golden

Fleece. All at once, Jason

bethought himself of the galley's miraculous

figure-head. "O, daughter of the

Talking Oak," cried he, "how shall we

set to work to get our vessel into the water?" "Seat yourselves,"

answered the image (for it had known what

had ought to be done from the very first, and was only waiting for the

question

to be put), — "seat yourselves, and handle your oars, and let Orpheus

play

upon his harp." Immediately the

fifty heroes got on board, and seizing their oars, held

them perpendicularly in the air, while Orpheus (who liked such a task

far

better than rowing) swept his fingers across the harp. At the first

ringing

note of the music, they felt the vessel stir. Orpheus thrummed away

briskly,

and the galley slid at once into the sea, dipping her prow so deeply

that the

figure-head drank the wave with its marvelous lips, and rising again as

buoyant

as a swan. The rowers plied their fifty oars; the white foam boiled up

before

the prow; the water gurgled and bubbled in their wake; while Orpheus

continued

to play so lively a strain of music, that the vessel seemed to dance

over the

billows by way of keeping time to it. Thus triumphantly did the Argo

sail out

of the harbor, amidst the huzzas and good wishes of everybody except

the wicked

old Pelias, who stood on a promontory, scowling at her, and wishing

that he

could blow out of his lungs the tempest of wrath that was in his heart,

and so

sink the galley with all on board. When they had sailed above fifty

miles over

the sea, Lynceus happened to cast his sharp eyes behind, and said that

there

was this bad-hearted king, still perched upon the promontory, and

scowling so

gloomily that it looked like a black thunder-cloud in that quarter of

the horizon. In order to make the

time pass away more pleasantly during the voyage,

the heroes talked about the Golden Fleece. It originally belonged, it

appears,

to a Bœotian ram, who had taken on his back two children, when in

danger of

their lives, and fled with them over land and sea as far as Colchis.

One of the

children, whose name was Helle, fell into the sea and was drowned. But

the

other (a little boy, named Phrixus) was brought safe ashore by the

faithful

ram, who, however, was so exhausted that he immediately lay down and

died. In

memory of this good deed, and as a token of his true heart, the fleece

of the

poor dead ram was miraculously changed to gold, and became one of the

most

beautiful objects ever seen on earth. It was hung upon a tree in a

sacred grove,

where it had now been kept I know not how many years, and was the envy

of

mighty kings, who had nothing so magnificent in any of their palaces. If I were to tell

you all the adventures of the Argonauts, it would take

me till nightfall, and perhaps a great deal longer. There was no lack

of

wonderful events, as you may judge from what you have already heard. At

a

certain island, they were hospitably received by King Cyzicus, its

sovereign,

who made a feast for them, and treated them like brothers. But the

Argonauts

saw that this good king looked downcast and very much troubled, and

they

therefore inquired of him what was the matter. King Cyzicus hereupon

informed

them that he and his subjects were greatly abused and incommoded by the

inhabitants of a neighboring mountain, who made war upon them, and

killed many

people, and ravaged the country. And while they were talking about it,

Cyzicus

pointed to the mountain, and asked Jason and his companions what they

saw

there. "I see some very

tall objects," answered Jason; "but they

are at such a distance that I cannot distinctly make out what they are.

To tell

your majesty the truth, they look so very strangely that I am inclined

to think

them clouds, which have chanced to take something like human shapes." "I see them very

plainly," remarked Lynceus, whose eyes, you

know, were as far-sighted as a telescope. "They are a band of enormous

giants, all of whom have six arms apiece, and a club, a sword, or some

other

weapon in each of their hands." "You have excellent

eyes," said King Cyzicus. "Yes; they

are six-armed giants, as you say, and these are the enemies whom I and

my

subjects have to contend with." The next day, when

the Argonauts were about setting sail, down came

these terrible giants, stepping a hundred yards at a stride,

brandishing their

six arms apiece, and looking formidable, so far aloft in the air. Each

of these

monsters was able to carry on a whole war by himself, for with one arm

he could

fling immense stones, and wield a club with another, and a sword with a

third,

while the fourth was poking a long spear at the enemy, and the fifth

and sixth

were shooting him with a bow and arrow. But, luckily, though the giants

were so

huge, and had so many arms, they had each but one heart, and that no

bigger nor

braver than the heart of an ordinary man. Besides, if they had been

like the

hundred-armed Briareus, the brave Argonauts would have given them their

hands

full of fight. Jason and his friends went boldly to meet them, slew a

great

many, and made the rest take to their heels, so that if the giants had

had six

legs apiece instead of six arms, it would have served them better to

run away

with. Another strange

adventure happened when the voyagers came to Thrace,

where they found a poor blind king, named Phineus, deserted by his

subjects,

and living in a very sorrowful way, all by himself: On Jason's

inquiring

whether they could do him any service, the king answered that he was

terribly

tormented by three great winged creatures, called Harpies, which had

the faces

of women, and the wings, bodies, and claws of vultures. These ugly

wretches

were in the habit of snatching away his dinner, and allowed him no

peace of his

life. Upon hearing this, the Argonauts spread a plentiful feast on the

sea-shore, well knowing, from what the blind king said of their

greediness,

that the Harpies would snuff up the scent of the victuals, and quickly

come to

steal them away. And so it turned out; for, hardly was the table set,

before

the three hideous vulture women came flapping their wings, seized the

food in

their talons, and flew off as fast as they could. But the two sons of

the North

Wind drew their swords, spread their pinions, and set off through the

air in

pursuit of the thieves, whom they at last overtook among some islands,

after a

chase of hundreds of miles. The two winged youths blustered terribly at

the

Harpies (for they had the rough temper of their father), and so

frightened them

with their drawn swords, that they solemnly promised never to trouble

King

Phineus again. Then the Argonauts

sailed onward and met with many other marvelous

incidents, any one of which would make a story by itself. At one time

they

landed on an island, and were reposing on the grass, when they suddenly

found

themselves assailed by what seemed a shower of steel-headed arrows.

Some of

them stuck in the ground, while others hit against their shields, and

several

penetrated their flesh. The fifty heroes started up, and looked about

them for

the hidden enemy, but could find none, nor see any spot, on the whole

island,

where even a single archer could lie concealed. Still, however, the

steel-headed arrows came whizzing among them; and, at last, happening

to look

upward, they beheld a large flock of birds, hovering and wheeling

aloft, and

shooting their feathers down upon the Argonauts. These feathers were

the

steel-headed arrows that had so tormented them. There was no

possibility of

making any resistance; and the fifty heroic Argonauts might all have

been

killed or wounded by a flock of troublesome birds, without ever setting

eyes on

the Golden Fleece, if Jason had not thought of asking the advice of the

oaken

image. So he ran to the

galley as fast as his legs would carry him. "O, daughter of the

Speaking Oak," cried he, all out of

breath, "we need your wisdom more than ever before! We are in great

peril

from a flock of birds, who are shooting us with their steel-pointed

feathers.

What can we do to drive them away?" "Make a clatter on

your shields," said the image. On receiving this

excellent counsel, Jason hurried back to his

companions (who were far more dismayed than when they fought with the

six-armed

giants), and bade them strike with their swords upon their brazen

shields. Forthwith

the fifty heroes set heartily to work, banging with might and main, and

raised

such a terrible clatter, that the birds made what haste they could to

get away;

and though they had shot half the feathers out of their wings, they

were soon

seen skimming among the clouds, a long distance off, and looking like a

flock of

wild geese. Orpheus celebrated this victory by playing a triumphant

anthem on

his harp, and sang so melodiously that Jason begged him to desist,

lest, as the

steel-feathered birds had been driven away by an ugly sound, they might

be

enticed back again by a sweet one. While the Argonauts

remained on this island, they saw a small vessel

approaching the shore, in which were two young men of princely

demeanor, and

exceedingly handsome, as young princes generally were, in those days.

Now, who

do you imagine these two voyagers turned out to be? Why, if you will

believe

me, they were the sons of that very Phrixus, who, in his childhood, had

been

carried to Colchis on the back of the golden-fleeced ram. Since that

time,

Phrixus had married the king's daughter; and the two young princes had

been

born and brought up at Colchis, and had spent their play-days in the

outskirts

of the grove, in the center of which the Golden Fleece was hanging upon

a tree.

They were now on their way to Greece, in hopes of getting back a

kingdom that

had been wrongfully taken from their father. When the princes

understood whither the Argonauts were going, they

offered to turn back, and guide them to Colchis. At the same time,

however,

they spoke as if it were very doubtful whether Jason would succeed in

getting

the Golden Fleece. According to their account, the tree on which it

hung was

guarded by a terrible dragon, who never failed to devour, at one

mouthful,

every person who might venture within his reach. "There are other

difficulties in the way," continued the young

princes. "But is not this enough? Ah, brave Jason, turn back before it

is

too late. It would grieve us to the heart, if you and your nine and

forty brave

companions should be eaten up, at fifty mouthfuls, by this execrable

dragon." "My young friends,"

quietly replied Jason, "I do not

wonder that you think the dragon very terrible. You have grown up from

infancy

in the fear of this monster, and therefore still regard him with the

awe that

children feel for the bugbears and hobgoblins which their nurses have

talked to

them about. But, in my view of the matter, the dragon is merely a

pretty large

serpent, who is not half so likely to snap me up at one mouthful as I

am to cut

off his ugly head, and strip the skin from his body. At all events,

turn back

who may, I will never see Greece again, unless I carry with me the

Golden

Fleece." "We will none of us

turn back!" cried his nine and forty brave

comrades. "Let us get on board the galley this instant; and if the

dragon

is to make a breakfast of us, much good may it do him." And Orpheus (whose

custom it was to set everything to music) began to

harp and sing most gloriously, and made every mother's son of them feel

as if

nothing in this world were so delectable as to fight dragons, and

nothing so

truly honorable as to be eaten up at one mouthful, in case of the

worst. After this (being

now under the guidance of the two princes, who were

well acquainted with the way), they quickly sailed to Colchis. When the

king of

the country, whose name was Ætes, heard of their arrival, he instantly

summoned

Jason to court. The king was a stern and cruel looking potentate; and

though he

put on as polite and hospitable an expression as he could, Jason did

not like

his face a whit better than that of the wicked King Pelias, who

dethroned his

father. "You are welcome, brave Jason," said King Ætes. "Pray,

are you on a pleasure voyage? — Or do you meditate the discovery of

unknown

islands? — or what other cause has procured me the happiness of seeing

you at

my court?" "Great sir," replied

Jason, with an obeisance — for Chiron had

taught him how to behave with propriety, whether to kings or beggars —

"I

have come hither with a purpose which I now beg your majesty's

permission to

execute. King Pelias, who sits on my father's throne (to which he has

no more

right than to the one on which your excellent majesty is now seated),

has

engaged to come down from it, and to give me his crown and sceptre,

provided I

bring him the Golden Fleece. This, as your majesty is aware, is now

hanging on

a tree here at Colchis; and I humbly solicit your gracious leave to

take it

away." In spite of himself, the king's face twisted itself into an

angry

frown; for, above all things else in the world, he prized the Golden

Fleece, and

was even suspected of having done a very wicked act, in order to get it

into

his own possession. It put him into the worst possible humor,

therefore, to

hear that the gallant Prince Jason, and forty-nine of the bravest young

warriors of Greece, had come to Colchis with the sole purpose of taking

away

his chief treasure. "Do you know," asked

King Ætes, eyeing Jason very sternly,

"what are the conditions which you must fulfill before getting

possession

of the Golden Fleece?" "I have heard,"

rejoined the youth, "that a dragon lies

beneath the tree on which the prize hangs, and that whoever approaches

him runs

the risk of being devoured at a mouthful." "True," said the

king, with a smile that did not look

particularly good-natured. "Very true, young man. But there are other

things as hard, or perhaps a little harder, to be done before you can

even have

the privilege of being devoured by the dragon. For example, you must

first tame

my two brazen-footed and brazen-lunged bulls, which Vulcan, the

wonderful blacksmith,

made for me. There is a furnace in each of their stomachs; and they

breathe

such hot fire out of their mouths and nostrils, that nobody has

hitherto gone

nigh them without being instantly burned to a small, black cinder. What

do you

think of this, my brave Jason?" "I must encounter

the peril," answered Jason, composedly,

"since it stands in the way of my purpose." "After taming the

fiery bulls," continued King Ætes, who was

determined to scare Jason if possible, "you must yoke them to a plow,

and

must plow the sacred earth in the Grove of Mars, and sow some of the

same

dragon's teeth from which Cadmus raised a crop of armed men. They are

an unruly

set of reprobates, those sons of the dragon's teeth; and unless you

treat them

suitably, they will fall upon you sword in hand. You and your nine and

forty

Argonauts, my bold Jason, are hardly numerous or strong enough to fight

with

such a host as will spring up." "My master Chiron,"

replied Jason, "taught me, long ago,

the story of Cadmus. Perhaps I can manage the quarrelsome sons of the

dragon's

teeth as well as Cadmus did." "I wish the dragon

had him," muttered King Ætes to himself,

"and the four-footed pedant, his schoolmaster, into the bargain. Why,

what

a foolhardy, self-conceited coxcomb he is! We'll see what my

fire-breathing

bulls will do for him. Well, Prince Jason," he continued, aloud, and as

complaisantly as he could, "make yourself comfortable for to-day, and

to-morrow morning, since you insist upon it, you shall try your skill

at the

plow." While the king

talked with Jason, a beautiful young woman was standing

behind the throne. She fixed her eyes earnestly upon the youthful

stranger, and

listened attentively to every word that was spoken; and when Jason

withdrew

from the king's presence, this young woman followed him out of the

room. "I am the king's

daughter," she said to him, "and my name

is Medea. I know a great deal of which other young princesses are

ignorant, and

can do many things which they would be afraid so much as to dream of.

If you

will trust to me, I can instruct you how to tame the fiery bulls, and

sow the

dragon's teeth, and get the Golden Fleece." "Indeed, beautiful

princess," answered Jason, "if you

will do me this service, I promise to be grateful to you my whole life

long."'

Gazing at Medea, he beheld a wonderful intelligence in her face. She

was one of

those persons whose eyes are full of mystery; so that, while looking

into them,

you seem to see a very great way, as into a deep well, yet can never be

certain

whether you see into the farthest depths, or whether there be not

something

else hidden at the bottom. If Jason had been capable of fearing

anything, he

would have been afraid of making this young princess his enemy; for,

beautiful

as she now looked, she might, the very next instant, become as terrible

as the

dragon that kept watch over the Golden Fleece. "Princess," he

exclaimed, "you seem indeed very wise and

very powerful. But how can you help me to do the things of which you

speak? Are

you an enchantress?" "Yes, Prince Jason,"

answered Medea, with a smile, "you

have hit upon the truth. I am an enchantress. Circe, my father's

sister, taught

me to be one, and I could tell you, if I pleased, who was the old woman

with

the peacock, the pomegranate, and the cuckoo staff, whom you carried

over the

river; and, likewise, who it is that speaks through the lips of the

oaken

image, that stands in the prow of your galley. I am acquainted with

some of

your secrets, you perceive. It is well for you that I am favorably

inclined;

for, otherwise, you would hardly escape being snapped up by the

dragon." "I should not so

much care for the dragon," replied Jason,

"if I only knew how to manage the brazen-footed and fiery-lunged

bulls." "If you are as brave

as I think you, and as you have need to

be," said Medea, "your own bold heart will teach you that there is

but one way of dealing with a mad bull. What it is I leave you to find

out in

the moment of peril. As for the fiery breath of these animals, I have a

charmed

ointment here, which will prevent you from being burned up, and cure

you if you

chance to be a little scorched." So she put a golden

box into his hand, and directed him how to apply the

perfumed unguent which it contained, and where to meet her at midnight.

"Only be brave,"

added she, "and before daybreak the

brazen bulls shall be tamed." The young man

assured her that his heart would not fail him. He then

rejoined his comrades, and told them what had passed between the

princess and

himself, and warned them to be in readiness in case there might be need

of

their help. At the appointed hour he met the beautiful Medea on the

marble

steps of the king's palace. She gave him a basket, in which were the

dragon's

teeth, just as they had been pulled out of the monster's jaws by

Cadmus, long

ago. Medea then led Jason down the palace steps, and through the silent

streets

of the city, and into the royal pasture ground, where the two

brazen-footed

bulls were kept. It was a starry night, with a bright gleam along the

eastern

edge of the sky, where the moon was soon going to show herself. After

entering

the pasture, the princess paused and looked around. "There they are,"

said she, "reposing themselves and

chewing their fiery cuds in that farthest corner of the field. It will

be

excellent sport, I assure you, when they catch a glimpse of your

figure. My

father and all his court delight in nothing so much as to see a

stranger trying

to yoke them, in order to come at the Golden Fleece. It makes a holiday

in

Colchis whenever such a thing happens. For my part, I enjoy it

immensely. You

cannot imagine in what a mere twinkling of an eye their hot breath

shrivels a

young man into a black cinder." "Are you sure,

beautiful Medea," asked Jason, "quite

sure, that the unguent in the gold box will prove a remedy against

those

terrible burns?" "If you doubt, if

you are in the least afraid," said the

princess, looking him in the face by the dim starlight, "you had better

never have been born than to go a step nigher to the bulls." But Jason had set

his heart steadfastly on getting the Golden Fleece;

and I positively doubt whether he would have gone back without it, even

had he

been certain of finding himself turned into a red-hot cinder, or a

handful of

white ashes, the instant he made a step farther. He therefore let go

Medea's

hand, and walked boldly forward in the direction whither she had

pointed. At

some distance before him he perceived four streams of fiery vapor,

regularly

appearing and again vanishing, after dimly lighting up the surrounding

obscurity.

These, you will understand, were caused by the breath of the brazen

bulls,

which was quietly stealing out of their four nostrils, as they lay

chewing

their cuds. At the first two or

three steps which Jason made, the four fiery streams

appeared to gush out somewhat more plentifully; for the two brazen

bulls had

heard his foot tramp, and were lifting up their hot noses to snuff the

air. He

went a little farther, and by the way in which the red vapor now

spouted forth,

he judged that the creatures had got upon their feet. Now he could see

glowing

sparks, and vivid jets of flame. At the next step, each of the bulls

made the

pasture echo with a terrible roar, while the burning breath, which they

thus

belched forth, lit up the whole field with a momentary flash. One other

stride

did bold Jason make; and, suddenly as a streak of lightning, on came

these

fiery animals, roaring like thunder, and sending out sheets of white

flame,

which so kindled up the scene that the young man could discern every

object more

distinctly than by daylight. Most distinctly of all he saw the two

horrible

creatures galloping right down upon him, their brazen hoofs rattling

and

ringing over the ground, and their tails sticking up stiffly into the

air, as

has always been the fashion with angry bulls. Their breath scorched the

herbage

before them. So intensely hot it was, indeed, that it caught a dry tree

under

which Jason was now standing, and set it all in a light blaze. But as

for Jason

himself (thanks to Medea's enchanted ointment), the white flame curled

around

his body, without injuring him a jot more than if he had been made of

asbestos. Greatly encouraged

at finding himself not yet turned into a cinder, the

young man awaited the attack of the bulls. Just as the brazen brutes

fancied

themselves sure of tossing him into the air, he caught one of them by

the horn,

and the other by his screwed-up tail, and held them in a gripe like

that of an

iron vice, one with his right hand, the other with his left. Well, he

must have

been wonderfully strong in his arms, to be sure. But the secret of the

matter

was, that the brazen bulls were enchanted creatures, and that Jason had

broken

the spell of their fiery fierceness by his bold way of handling them.

And, ever

since that time, it has been the favorite method of brave men, when

danger

assails them, to do what they call "taking the bull by the horns";

and to gripe him by the tail is pretty much the same thing — that is,

to throw

aside fear, and overcome the peril by despising it. It was now easy to

yoke the

bulls, and to harness them to the plow, which had lain rusting on the

ground

for a great many years gone by; so long was it before anybody could be

found

capable of plowing that piece of land. Jason, I suppose, had been

taught how to

draw a furrow by the good old Chiron, who, perhaps, used to allow

himself to be

harnessed to the plow. At any rate, our hero succeeded perfectly well

in

breaking up the greensward; and, by the time that the moon was a

quarter of her

journey up the sky, the plowed field lay before him, a large tract of

black

earth, ready to be sown with the dragon's teeth. So Jason scattered

them

broadcast, and harrowed them into the soil with a brush-harrow, and

took his

stand on the edge of the field, anxious to see what would happen next. "Must we wait long

for harvest time?" he inquired of Medea,

who was now standing by his side. "Whether sooner or

later, it will be sure to come," answered

the princess. "A crop of armed men never fails to spring up, when the

dragon's teeth have been sown." The moon was now

high aloft in the heavens, and threw its bright beams

over the plowed field, where as yet there was nothing to be seen. Any

farmer,

on viewing it, would have said that Jason must wait weeks before the

green

blades would peep from among the clods, and whole months before the

yellow

grain would be ripened for the sickle. But by and by, all over the

field, there

was something that glistened in the moonbeams, like sparkling drops of

dew.

These bright objects sprouted higher, and proved to be the steel heads

of

spears. Then there was a dazzling gleam from a vast number of polished

brass

helmets, beneath which, as they grew farther out of the soil, appeared

the dark

and bearded visages of warriors, struggling to free themselves from the

imprisoning earth. The first look that they gave at the upper world was

a glare

of wrath and defiance. Next were seen their bright breastplates; in

every right

hand there was a sword or a spear, and on each left arm a shield; and

when this

strange crop of warriors had but half grown out of the earth, they

struggled — such

was their impatience of restraint — and, as it were, tore themselves up

by the

roots. Wherever a dragon's tooth had fallen, there stood a man armed

for

battle. They made a clangor with their swords against their shields,

and eyed

one another fiercely; for they had come into this beautiful world, and

into the

peaceful moonlight, full of rage and stormy passions, and ready to take

the

life of every human brother, in recompense of the boon of their own

existence. There have been many

other armies in the world that seemed to possess

the same fierce nature with the one which had now sprouted from the

dragon's

teeth; but these, in the moonlit field, were the more excusable,

because they

never had women for their mothers. And how it would have rejoiced any

great

captain, who was bent on conquering the world, like Alexander or

Napoleon, to

raise a crop of armed soldiers as easily as Jason did! For a while, the

warriors stood flourishing their weapons, clashing their swords against

their

shields, and boiling over with the red-hot thirst for battle. Then they

began

to shout — "Show us the enemy! Lead us to the charge! Death or

victory!" "Come on, brave comrades! Conquer or die!" and a

hundred other outcries, such as men always bellow forth on a battle

field, and

which these dragon people seemed to have at their tongues' ends. At

last, the

front rank caught sight of Jason, who, beholding the flash of so many

weapons

in the moonlight, had thought it best to draw his sword. In a moment

all the

sons of the dragon's teeth appeared to take Jason for an enemy; and

crying with

one voice, "Guard the Golden Fleece!" they ran at him with uplifted

swords and protruded spears. Jason knew that it would be impossible to

withstand this blood-thirsty battalion with his single arm, but

determined,

since there was nothing better to be done, to die as valiantly as if he

himself

had sprung from a dragon's tooth. Medea, however, bade

him snatch up a stone from the ground. "Throw it among them

quickly!" cried she. "It is the only

way to save yourself." The armed men were

now so nigh that Jason could discern the fire

flashing out of their enraged eyes, when he let fly the stone, and saw

it

strike the helmet of a tall warrior, who was rushing upon him with his

blade

aloft. The stone glanced from this man's helmet to the shield of his

nearest

comrade, and thence flew right into the angry face of another, hitting

him

smartly between the eyes. Each of the three who had been struck by the

stone

took it for granted that his next neighbor had given him a blow; and

instead of

running any farther towards Jason, they began to fight among

themselves. The

confusion spread through the host, so that it seemed scarcely a moment

before they

were all hacking, hewing, and stabbing at one another, lopping off

arms, heads,

and legs and doing such memorable deeds that Jason was filled with

immense

admiration; although, at the same time, he could not help laughing to

behold

these mighty men punishing each other for an offense which he himself

had

committed. In an incredibly short space of time (almost as short,

indeed, as it

had taken them to grow up), all but one of the heroes of the dragon's

teeth

were stretched lifeless on the field. The last survivor, the bravest

and

strongest of the whole, had just force enough to wave his crimson sword

over

his head and give a shout of exultation, crying, "Victory! Victory!

Immortal fame!" when he himself fell down, and lay quietly among his

slain

brethren. And there was the

end of the army that had sprouted from the dragon's

teeth. That fierce and feverish fight was the only enjoyment which they

had

tasted on this beautiful earth. "Let them sleep in

the bed of honor," said the Princess Medea,

with a sly smile at Jason. "The world will always have simpletons

enough,

just like them, fighting and dying for they know not what, and fancying

that

posterity will take the trouble to put laurel wreaths on their rusty

and

battered helmets. Could you help smiling, Prince Jason, to see the

self-conceit

of that last fellow, just as he tumbled down?" "It made me very

sad," answered Jason, gravely. "And, to

tell you the truth, princess, the Golden Fleece does not appear so well

worth

the winning, after what I have here beheld!" "You will think

differently in the morning," said Medea.

"True, the Golden Fleece may not be so valuable as you have thought it;

but then there is nothing better in the world; and one must needs have

an

object, you know. Come! Your night's work has been well performed; and

to-morrow you can inform King Ætes that the first part of your allotted

task is

fulfilled." Agreeably to Medea's

advice, Jason went betimes in the morning to the

palace of King Ætes. Entering the presence chamber, he stood at the

foot of the

throne, and made a low obeisance. "Your eyes look

heavy, Prince Jason," observed the king;

"you appear to have spent a sleepless night. I hope you have been

considering the matter a little more wisely, and have concluded not to

get

yourself scorched to a cinder, in attempting to tame my brazen-lunged

bulls." "That is already

accomplished, may it please your majesty,"

replied Jason. "The bulls have been tamed and yoked; the field has been

plowed; the dragon's teeth have been sown broadcast, and harrowed into

the

soil; the crop of armed warriors have sprung up, and they have slain

one

another, to the last man. And now I solicit your majesty's permission

to

encounter the dragon, that I may take down the Golden Fleece from the

tree, and

depart, with my nine and forty comrades." King Ætes scowled,

and looked very angry and excessively disturbed; for

he knew that, in accordance with his kingly promise, he ought now to

permit

Jason to win the Fleece, if his courage and skill should enable him to

do so.

But, since the young man had met with such good luck in the matter of

the

brazen bulls and the dragon's teeth, the king feared that he would be

equally

successful in slaying the dragon. And therefore, though he would gladly

have

seen Jason snapped up at a mouthful, he was resolved (and it was a very

wrong

thing of this wicked potentate) not to run any further risk of losing

his

beloved Fleece. "You never would

have succeeded in this business, young man,"

said he, "if my undutiful daughter Medea had not helped you with her

enchantments. Had you acted fairly, you would have been, at this

instant, a

black cinder, or a handful of white ashes. I forbid you, on pain of

death, to

make any more attempts to get the Golden Fleece. To speak my mind

plainly, you

shall never set eyes on so much as one of its glistening locks." Jason left the

king's presence in great sorrow and anger. He could think

of nothing better to be done than to summon together his forty-nine

brave

Argonauts, march at once to the Grove of Mars, slay the dragon, take

possession

of the Golden Fleece, get on board the Argo, and spread all sail for

Iolchos.

The success of this scheme depended, it is true, on the doubtful point

whether

all the fifty heroes might not be snapped up, at so many mouthfuls, by

the

dragon. But, as Jason was hastening down the palace steps, the Princess

Medea

called after him, and beckoned him to return. Her black eyes shone upon

him

with such a keen intelligence, that he felt as if there were a serpent

peeping

out of them; and, although she had done him so much service only the

night

before, he was by no means very certain that she would not do him an

equally

great mischief before sunset. These enchantresses, you must know, are

never to

be depended upon. "What says King Ætes, my royal and upright father?" inquired Medea, slightly smiling. "Will he give you the Golden Fleece, without any further risk or trouble?"  "Look yonder,"

Medea whispered. "Do you see it?"

"On the contrary,"

answered Jason, "he is very angry with

me for taming the brazen bulls and sowing the dragon's teeth. And he

forbids me

to make any more attempts, and positively refuses to give up the Golden

Fleece,

whether I slay the dragon or no." "Yes, Jason," said

the princess, "and I can tell you

more. Unless you set sail from Colchis before to-morrow's sunrise, the

king

means to burn your fifty-oared galley, and put yourself and your

forty-nine

brave comrades to the sword. But be of good courage. The Golden Fleece

you

shall have, if it lies within the power of my enchantments to get it

for you.

Wait for me here an hour before midnight." At the appointed

hour you might again have seen Prince Jason and the

Princess Medea, side by side, stealing through the streets of Colchis,

on their

way to the sacred grove, in the center of which the Golden Fleece was

suspended

to a tree. While they were crossing the pasture ground, the brazen

bulls came

towards Jason, lowing, nodding their heads, and thrusting forth their

snouts,

which, as other cattle do, they loved to have rubbed and caressed by a

friendly

hand. Their fierce nature was thoroughly tamed; and, with their

fierceness, the

two furnaces in their stomachs had likewise been extinguished, insomuch

that

they probably enjoyed far more comfort in grazing and chewing their

cuds than

ever before. Indeed, it had heretofore been a great inconvenience to

these poor

animals, that, whenever they wished to eat a mouthful of grass, the

fire out of

their nostrils had shriveled it up, before they could manage to crop

it. How

they contrived to keep themselves alive is more than I can imagine. But

now,

instead of emitting jets of flame and streams of sulphurous vapor, they

breathed the very sweetest of cow breath. After kindly patting

the bulls, Jason followed Medea's guidance into the

Grove of Mars, where the great oak trees, that had been growing for

centuries,

threw so thick a shade that the moonbeams struggled vainly to find

their way

through it. Only here and there a glimmer fell upon the leaf-strewn

earth, or

now and then a breeze stirred the boughs aside, and gave Jason a

glimpse of the

sky, lest, in that deep obscurity, he might forget that there was one,

overhead. At length, when they had gone farther and farther into the

heart of

the duskiness, Medea squeezed Jason's hand. "Look yonder," she

whispered. "Do you see it?" Gleaming among the

venerable oaks, there was a radiance, not like the

moonbeams, but rather resembling the golden glory of the setting sun.

It

proceeded from an object, which appeared to be suspended at about a

man's

height from the ground, a little farther within the wood. "What is it?" asked

Jason. "Have you come so

far to seek it," exclaimed Medea, "and

do you not recognize the meed of all your toils and perils, when it

glitters

before your eyes? It is the Golden Fleece." Jason went onward a

few steps farther, and then stopped to gaze. O, how

beautiful it looked, shining with a marvelous light of its own, that

inestimable prize which so many heroes had longed to behold, but had

perished

in the quest of it, either by the perils of their voyage, or by the

fiery

breath of the brazen-lunged bulls. "How gloriously it

shines!" cried Jason, in a rapture.

"It has surely been dipped in the richest gold of sunset. Let me hasten

onward, and take it to my bosom." "Stay," said Medea,

holding him back. "Have you forgotten

what guards it?" To say the truth, in

the joy of beholding the object of his desires, the

terrible dragon had quite slipped out of Jason's memory. Soon, however,

something came to pass, that reminded him what perils were still to be

encountered. An antelope, that probably mistook the yellow radiance for

sunrise, came bounding fleetly through the grove. He was rushing

straight

towards the Golden Fleece, when suddenly there was a frightful hiss,

and the

immense head and half the scaly body of the dragon was thrust forth

(for he was

twisted round the trunk of the tree on which the Fleece hung), and

seizing the

poor antelope, swallowed him with one snap of his jaws. After this feat, the

dragon seemed sensible that some other living

creature was within reach, on which he felt inclined to finish his

meal. In

various directions he kept poking his ugly snout among the trees,

stretching

out his neck a terrible long way, now here, now there, and now close to

the

spot where Jason and the princess were hiding behind an oak. Upon my

word, as

the head came waving and undulating through the air, and reaching

almost within

arm's length of Prince Jason, it was a very hideous and uncomfortable

sight.

The gape of his enormous jaws was nearly as wide as the gateway of the

king's

palace. "Well, Jason,"

whispered Medea (for she was ill natured, as

all enchantresses are, and wanted to make the bold youth tremble),

"what

do you think now of your prospect of winning the Golden Fleece?" Jason answered only

by drawing his sword, and making a step forward. "Stay, foolish

youth," said Medea, grasping his arm. "Do

not you see you are lost, without me as your good angel? In this gold

box I