| Web

and Book

design, |

Click

Here to return to |

ST. BOTOLPH'S

I

TOWN AS IT WAS IN THE BEGINNING

To Sir Ferdinando Gorges,

the intimate friend of Sir Walter Raleigh and a man of much more than

common

interest in the history of Elizabethan England, is due the credit of

the first

enduring settlement in the environs of Boston. John Smith had skirted

the coast

of New England and looked with some care into Boston Harbour before

Gorges

came; Miles Standish had pushed up from Plymouth to trade with the

Indians of

this section; and Thomas Weston, soldier of fortune, had

established a

temporary trading-post in what is now Weymouth. But it remained for

Gorges and

his son Robert to plant firmly upon our shores the standard of England

and to

reiterate that that was the country to which, by virtue of the

Cabots, those

shores rightly belonged.

The Cabots, to be sure, had

come a century and a quarter before and, since their time,

explorers of

several other nations had ventured to the new world — one of

them

even going so

far as to carve his name upon the continent. But an English king had

fitted out

the "carvels" of John and Sebastian Cabot; and

English kings

were

not in the habit of forgetting incidents of that sort. The letter in

which

Sebastian Cabot relates the story of those Bristol vessels is

very

quaint and

interesting. "When my father," he writes, "departed from Venice

many yeers since to dwell in England, to follow the trade of

merchandizes, he

took me with him to the city of London, while I was very yong, yet

having,

nevertheless, some knowledge of letters, of humanity and of the Sphere.

And

when my father died in that time when news was brought that Don

Christofer

Colonus Genuse [Columbus] had discovered the coasts of India

whereof was great

talke in all the court of King Henry the Seventh, who then raigned,

inso much

that all men with great admiration affirmed it to be a thing more

divine than

humane, to sail by the West into the East where spices growe, by a way

that was

never known before; by this fame and report there increased in my heart

a great

flame of desire to attempt some notable thing. And, understanding by

reason of

the Sphere, that if I should saile by way of the Northwest winde, I

should by a

shorter track come into India, I thereupon caused the king to be

advertised of

my devise, who immediately commanded two Carvels to bee furnished with

all

things appertaining to the voiage, which was, as farre as I remember,

in the

yeere 1496, in the beginning of Sommer.

"I began therefore to

saile toward the Northwest, not thinking to find any other land than

that of

Cathay, and from thence to turn toward India, but after certaine dayes

I found

that the land ranne towards the North, which was to me a great

displeasure.

Nevertheless, sailing along the coast to see if I could find any gulfe

that

turned, I found the land still continuing to the 56 deg. under

our

pole. And

seeing that there the coast turned toward the East, despairing to find

the

passage, I turned back again, and sailed down by the coast of that land

towards

the Equinoctiall (ever with intent to find the said passage to India)

and came

to that part of this firme land which is now called Florida, where my

victuals

failing, I departed from thence and returned into England,

where I

found great

tumults among the people, and preparation for warrs in Scotland: by

reason

whereof there was no more consideration had to this voyage."

But

barren

of immediate results as this voyage undoubtedly was it is of immense

importance

to us as the first link in the chain which, for so long, bound America

to

England.

Captain John Smith

The next link was, of

course, forged by Captain John Smith to whom New England as

well

as Virginia

owes more than it can ever repay. About one year before the settlement

of

Boston by the company which came with Winthrop Smith recapitulated the

affairs

of New England in the following lucid manner: "When I went

first

to the

North part of Virginia, [in 1614] where the Westerly colony [of 1607]

had been

planted, which had dissolved itself within a yeare, there was not one

Christian

in all the land. The country was then reputed a most rockie barren,

desolate

desart; but the good return I brought from thence, with the maps and

relations

I made of the country, which I made so manifest, some of them did

beleeve me,

and they were well embraced, both by the Londoners and the Westerlings,

for

whom I had promised to undertake it, thinking to have joyned them all

together.

Betwixt them there long was much contention. The Londoners,

indeed, went

bravely forward but in three or four yeares, I and my friends consumed

many

hundred pounds among the Plimothians, who only fed me but with delayes

promises

and excuses, but no performance of any kind to any purpose. In the

interim many

particular ships went thither, and finding my relations true, and that

I had

not taken that I brought home from the French men, as had beene

reported; yet

further for my paines to discredit me and my calling it New England,

they obscured

it and shadowed it with the title of Cannada, till, at my humble suit,

king

Charles confirmed it, with my map and booke, by the title of New

England. The

gaine thence returning did make the fame thereof so increase,

that

thirty

forty or fifty saile, went yearely only to trade and fish; but nothing

would be

done for a plantation till about some hundred of your Brownists of

England,

Amsterdam and Leyden, went to New Plimouth, whose humourous

ignorances caused

them for more than a yeare, to endure a wonderful deale of misery with

an

infinite patience; but those in time doing well diverse others have in

small

handfulls undertaken to goe there, to be

severall Lords and Kings of themselves...."

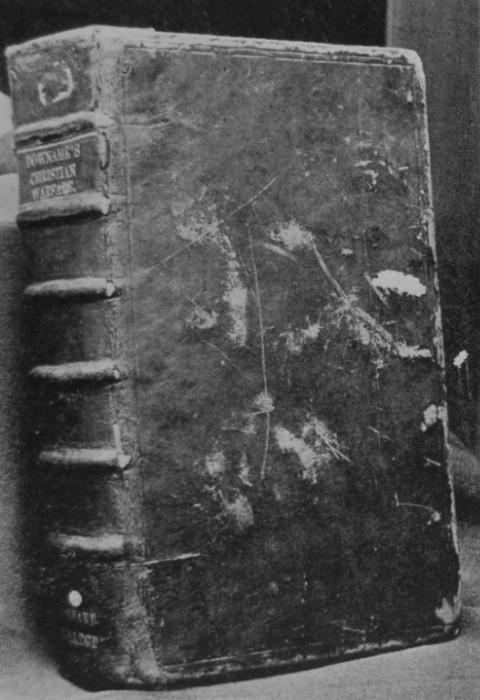

Cover and Title-Page of John Harvard's Book

The Gorges project,

certainly, aimed at nothing short of a principality and was

begun

in all pomp

and circumstance. To Greenwich on June 29, 1623, came the Dukes of

Buckingham

and Richmond, four earls and many lords and gentlemen to draw lots for

possessions in the new country. This imposing group was called the

Council for

New England and had been established under a charter granted in 1620 to

the

elder Gorges and thirty-nine other patentees. Gorges had had the good

luck to

acquaint Raleigh with the conspiracy of the Earl of Essex against Queen

Elizabeth and James I had valid reason, therefore, to appoint him

governor of

Plymouth in Devonshire. It was while pursuing his duties in Plymouth

that his

interest in New England was excited, by the mere accident, as he

relates, of

some Indians happening to be brought before him. At much pains he

learned from

them something of the nature of their country and his imagination was

soon

fired with the vision of golden harvests waiting in the

western

continent to

be reaped by such as he. Naturally sanguine and full of enthusiasm he

succeeded

in interesting in his project Sir John Popham, Lord Chief Justice of

the King's

Bench, through whose acquaintance with noblemen and connection at Court

the

coveted patent for making settlements in America was ere long

secured.

Then the success of the

Greenwich assembly — King James himself drew for Buckingham!

— seems to have

decided both Sir Ferdinando and his son to go at once to their

glittering new

world; and, a few weeks later, the latter sailed forth, armed with a

commission

as lieutenant of the Council with power to exercise

jurisdiction,

civil,

criminal, and ecclesiastical, over the whole of the New England coast.

The plan

was for him to settle not too far from Plymouth, absorb as

soon as

might be

the little group of men and women who were really laying there

the

foundations

of a nation and begin in masterful fashion the administration

of

the vast

province which was undeniably his — on paper.

At Weymouth Thomas Weston

had left a rude block-house and this Robert Gorges and his comrades

immediately

appropriated. In their company were several mechanics and tillers of

the soil

who proceeded to make themselves useful in the new land; but

of

most interest

to us because of their after-history, were three gentlemen colonists,

Samuel

Maverick, a, young man of means and education who established

at

what is now

Chelsea the first permanent house in the Bay colony, Rev.

William

Morrell, the

Church of England representative in the brave undertaking and William

Blackstone,

graduate of Cambridge University and destined to renown as the first

white settler

of what we to-day know as Boston.

It was in September, 1623,

that Robert Gorges landed in Weymouth. In the spring of 1624 he

returned to

England taking with him several of his comrades. Governor Bradford,

whom he

tried in vain to bully into obeisance observes mildly that Gorges did

not find

"the state of things heare to answer his Qualitie and condition." So

he stayed less than a year. Some of those who had come with him were

for trying

the thing longer, however. Even the Rev. Mr. Morrell put in a second

bitter

winter before giving up the attempt. Though he speaks feelingly of the

hard lot

of men who are "landed upon an unknown shore, peradventure

weake

in

number and naturall powers, for want of boats and carriages," and being

for this reason compelled with a whole empty continent before

them

"to

stay where they are first landed, having no means to remove

themselves or

their goods, be the place never so fruitlesse or inconvenient for

planting,

building houses, boats or stages, or the harbors never so

unfit

for fishing,

fowling or mooring their boats," — yet Morrell was none the

less

very

favourably impressed, as Smith and all the others had been, with the

natural

charms of New England. As the fruit of his sojourn we have a Latin poem

in

which the country is described in a genial and somewhat imaginative way.

The year that Morrell

returned to England (1625) was in all probability that in which William

Blackstone took up his abode across the bay, in Shawmut, opposite the

mouth of

the Charles. And it was in that same ,year, too, that Captain Wollaston

and his

party established themselves at the place since known as Mount

Wollaston, in

the town of Quincy.

Among Wollaston's companions

was one Thomas Morton "of Clifford's Inn, Gent.," a lawyer by

profession and an outlaw by practice. In the rather dull pages of early

New

England history Morton's escapades supply "colour," however, for

which we cannot be too grateful to him. The staid Plymouth people soon

came to

speak of him as the "Lord of Misrule" and there is no evidence

whatever that he failed to deserve the title. When Wollaston departed

to

Virginia on business he proceeded to become captain in his stead and,

naming

the settlement Mare Mount, — Merry Mount, — he

invited all

the settlers to have

a good time. They did so, according to Morton's own account —

in

the mad glad

bad way ever dear to roystering Englishmen. Not only did he

and

his followers

drink deep of the festal bowl but they made the Indians with whom they

traded

welcome to drink deep also. To the men savages were given arms and

ammunition

while to the women was extended the privilege of becoming the mates of

the

conquering English. The May Day of 1627 was celebrated in revelry run

riot.

Morton has left us a minute description of the pole used on this

occasion

" a goodly pine tree of 80 foote long... with a peare of bucks horns

nayled one, somewhat neare unto the top of it," while Governor Bradford

says they "set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing aboute it

many

days

togither, inviting the Indean women for their consorts, dancing and

frisking

togither (like so many fairies, or furies rather) and worse practices."

Bradford not unnaturally

failed to appreciate the "colour." Moreover, the settlers

could

not,

of course, have the natives furnished with firearms. So Morton was,

after some

difficulty, made a prisoner and shipped off to England. But he came

back again

the next year and for a considerable time was a veritable

thorn in

the flesh

to Endicott and his companions at Salem.

The Salem settlement was in

the nature of a rescuing party. For while Sir Ferdinando and his

friends had

been exhausting themselves upon the pomps and ceremonies of

colonization John

White, a Dorchester clergyman, had established a little group

of

"prudent

and honest men" in a kind of missionary settlement near what

is

now

Gloucester. Of these men Roger Conant with three others had stayed on

in the

face of much discouragement after their companions returned to England,

finally

removing to Naumkeag (Salem), — where

Endicott found

them — when he landed

early in the fall of 1628.

The rights of Endicott's men

to territory in New England were obtained by purchase from Sir

Ferdinando's

Council of Plymouth. The name adopted by them was that of "the

Massachusetts

Company." Very wisely, however, as matters turned out, Endicott and his

friends insisted that a charter be obtained from the Crown confirmatory

of the

grant from the

Council of Plymouth. And

though they sailed before the charter passed the seals, when it did so,

March

4, 1629, the rights of the colonists were defined as they never before

had

been, — and Charles I had placed in the hands of mere

subjects

powers which

many a king who came after him would have given much to revoke.

Though Endicott was the

"Governor of London's Plantation in the Massachusetts Bay of New

England" Matthew Cradock was the governor, — i. e. the

executive

business

head, — in the old country; and Cradock it was who, in July,

1629, submitted to

his fellow-members in England certain propositions, conceived by

himself,

which, reinforced as they were by the charter, were destined to work a

veritable revolution in the colonization of New England. Up to this

time there

seems to have been no thought whatever of transferring to the new land

the

actual government of the Company but Cradock made the startling

proposal that

just this should be done to the end that persons of worth and quality

might

deem it worth while to embark with their families for the

plantation. There is

still standing in Medford, near Boston, a house bearing the name of

this governor

and built for his use though he never came to occupy it. Between the

suggestion

of Cradock's plan at Deputy Goffe's house in London, in August, 1629,

and its

adoption a month later every member of the Company gave deep thought to

the

change involved. And, gradually, they came to see in it a way of escape

from

persecution and oppression. Reforms in England, whether of Church or

State,

seemed impossible. Strafford was at the head of the army and Laud in

control of

the Church. Illegal taxes were being levied on all hands and it looked

as if

Charles were resolved to rule the kingdom in his own

stiff-necked way,

disdaining the cooperation of any Parliament. Little hope indeed did

the Old

World offer to the liberty-loving, religious men who made up the bulk

of the

Puritan party!

Old House in Medford, built by Governor Craddock

The document by which these

men finally emancipated themselves has come down to us as the Cambridge

Agreement, so called because it was signed beneath the shadows and

probably

within the very walls of that venerable university whose traditions it

was

destined to transplant into a new world. It bore the date. August 26,

1629; and

was in the following words: —

"Upon due consideration

of the state of the Plantation now in hand for New England. Wherein we

whose

names are hereunto subscribed, have engaged ourselves, and having

weighed the

work in regard of the consequence, God's glory and the Church's good;

as also

in regard of the difficulties and discouragements which in all

probabilities

must be forecast upon the prosecution of this business; considering

withal that

this whole adventure grows upon the joint confidence we have in each

other's

fidelity and resolution herein, so as no man of us

would have adventured it

without the assurance of the rest; now

for the better encouragement of ourselves and others who shall

join with us in

this action, and to the end that every man may without scruple dispose

of his

estate and affairs as may best fit his preparation for this

voyage; it is

fully and faithfully agreed

among us,

and every one of us doth hereby freely and sincerely promise and bind

himself,

in the word of a Christian and in the presence of God, who is the

searcher of

all hearts, that we will so really endeavor the prosecution of this

work, as by

God's assistance we will be ready in our persons, and with

such of

our several

families as are to go with us, and such provision as we are able

conveniently

to furnish ourselves withal, to embark for the said Plantation by the

first of

March next, at such port or ports of this land as shall be agreed upon

by the

Company, to the end to pass the Seas (under God's protection) to

inhabit and

continue in New England: Provided always, that before the last of

September

next, the whole Government, together with the Patent for the said

Plantation,

be first, by an order of Court, legally transferred and

established to remain

with us and others which shall inhabit upon the said Plantation; and

provided

also, that if any shall be hindered by such just or inevitable let or

other

cause, to be allowed by three parts of four of these whose names are

hereunto

subscribed, then such persons for such times and during such lets, to

be discharged

of this bond. And we do further promise, every one for himself, that.

shall

fail to be ready by his own default by the day appointed, to

pay

for every

day's default the Sum of £3 to the use of the rest of the

company

who shall be

ready by the same day and time.

RICHARD SALTONSTALL,

THOMAS SHARPE,

THOMAS DUDLEY,

INCREASE NOWELL,

WILLIAM VASSALL,

JOHN WINTHROP,

NICHOLAS WEST,

WILLIAM PINCHON,

ISAAC JOHNSON,

KELLAM BROWNE,

JOHN HUMFRY,

WILLIAM COLBRON."

As important to this epoch-making agreement as the Prince of Denmark to the play of Hamlet is the sentence "Provided always, that before the last of September next, the whole Government, together with the Patent for the said Plantation, be first by an order of Court, legally transferred and established to remain with us and others which shall inhabit upon the said Plantation." This was the great condition, we must bear clearly in mind, upon which Saltonstall, Dudley, Winthrop and the rest agreed to leave the land where they had been born and bred, and "inhabit and continue" in a new land of which they knew nothing. Two months later John Winthrop was chosen head of the enterprise, with the style and title Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company. Emphatically, Boston has now "begun."