V

aptain

Armand Jacot of the Foreign Legion sat upon an outspread saddle

blanket at the foot of a stunted palm tree. His broad shoulders and

his close-cropped head rested in luxurious ease against the rough

bole of the palm. His long legs were stretched straight before him

overlapping the meager blanket, his spurs buried in the sandy soil of

the little desert oasis. The captain was taking his ease after a long

day of weary riding across the shifting sands of the desert. aptain

Armand Jacot of the Foreign Legion sat upon an outspread saddle

blanket at the foot of a stunted palm tree. His broad shoulders and

his close-cropped head rested in luxurious ease against the rough

bole of the palm. His long legs were stretched straight before him

overlapping the meager blanket, his spurs buried in the sandy soil of

the little desert oasis. The captain was taking his ease after a long

day of weary riding across the shifting sands of the desert.

Lazily

he puffed upon his cigarette and watched his orderly who was

preparing his evening meal. Captain Armand Jacot was well satisfied

with himself and the world. A little to his right rose the noisy

activity of his troop of sun-tanned veterans, released for the time

from the irksome trammels of discipline, relaxing tired muscles,

laughing, joking, and smoking as they, too, prepared to eat after a

twelve-hour fast. Among them, silent and taciturn, squatted five

white-robed Arabs, securely bound and under heavy guard.

It

was the sight of these that filled Captain Armand Jacot with the

pleasurable satisfaction of a duty well-performed. For a long, hot,

gaunt month he and his little troop had scoured the places of the

desert waste in search of a band of marauders to the sin-stained

account of which were charged innumerable thefts of camels, horses,

and goats, as well as murders enough to have sent the whole unsavory

gang to the guillotine several times over.

A

week before, he had come upon them. In the ensuing battle he had lost

two of his own men, but the punishment inflicted upon the marauders

had been severe almost to extinction. A half dozen, perhaps, had

escaped; but the balance, with the exception of the five prisoners,

had expiated their crimes before the nickel jacketed bullets of the

legionaries. And, best of all, the ring leader, Achmet ben Houdin,

was among the prisoners.

From

the prisoners Captain Jacot permitted his mind to traverse the

remaining miles of sand to the little garrison post where, upon the

morrow, he should find awaiting him with eager welcome his wife and

little daughter. His eyes softened to the memory of them, as they

always did. Even now he could see the beauty of the mother reflected

in the childish lines of little Jeanne's face, and both those faces

would be smiling up into his as he swung from his tired mount late

the following afternoon. Already he could feel a soft cheek pressed

close to each of his — velvet against leather.

His

reverie was broken in upon by the voice of a sentry summoning a

non-commissioned officer. Captain Jacot raised his eyes. The sun had

not yet set; but the shadows of the few trees huddled about the water

hole and of his men and their horses stretched far away into the east

across the now golden sand. The sentry was pointing in this

direction, and the corporal, through narrowed lids, was searching the

distance. Captain Jacot rose to his feet. He was not a man content to

see through the eyes of others. He must see for himself. Usually he

saw things long before others were aware that there was anything to

see — a trait that had won for him the sobriquet of Hawk. Now he

saw, just beyond the long shadows, a dozen specks rising and falling

among the sands. They disappeared and reappeared, but always they

grew larger. Jacot recognized them immediately. They were horsemen —

horsemen of the desert. Already a sergeant was running toward him.

The entire camp was straining its eyes into the distance. Jacot gave

a few terse orders to the sergeant who saluted, turned upon his heel

and returned to the men. Here he gathered a dozen who saddled their

horses, mounted and rode out to meet the strangers. The remaining men

disposed themselves in readiness for instant action. It was not

entirely beyond the range of possibilities that the horsemen riding

thus swiftly toward the camp might be friends of the prisoners bent

upon the release of their kinsmen by a sudden attack. Jacot doubted

this, however, since the strangers were evidently making no attempt

to conceal their presence. They were galloping rapidly toward the

camp in plain view of all. There might be treachery lurking beneath

their fair appearance; but none who knew The Hawk would be so

gullible as to hope to trap him thus.

The

sergeant with his detail met the Arabs two hundred yards from the

camp. Jacot could see him in conversation with a tall, white-robed

figure — evidently the leader of the band. Presently the sergeant

and this Arab rode side by side toward camp. Jacot awaited them. The

two reined in and dismounted before him.

"Sheik

Amor ben Khatour," announced the sergeant by way of

introduction.

Captain

Jacot eyed the newcomer. He was acquainted with nearly every

principal Arab within a radius of several hundred miles. This man he

never had seen. He was a tall, weather beaten, sour looking man of

sixty or more. His eyes were narrow and evil. Captain Jacot did not

relish his appearance.

"Well?"

he asked, tentatively.

The

Arab came directly to the point.

"Achmet

ben Houdin is my sister's son," he said. "If you will give

him into my keeping I will see that he sins no more against the laws

of the French."

Jacot

shook his head. "That cannot be," he replied. "I must

take him back with me. He will be properly and fairly tried by a

civil court. If he is innocent he will be released."

"And

if he is not innocent?" asked the Arab.

"He

is charged with many murders. For any one of these, if he is proved

guilty, he will have to die."

The

Arab's left hand was hidden beneath his burnous. Now he withdrew it

disclosing a large goatskin purse, bulging and heavy with coins. He

opened the mouth of the purse and let a handful of the contents

trickle into the palm of his right hand — all were pieces of good

French gold. From the size of the purse and its bulging proportions

Captain Jacot concluded that it must contain a small fortune. Sheik

Amor ben Khatour dropped the spilled gold pieces one by one back into

the purse. Jacot was eyeing him narrowly. They were alone. The

sergeant, having introduced the visitor, had withdrawn to some little

distance — his back was toward them. Now the sheik, having returned

all the gold pieces, held the bulging purse outward upon his open

palm toward Captain Jacot.

"Achmet

ben Houdin, my sister's son, MIGHT escape tonight," he said.

"Eh?"

Captain

Armand Jacot flushed to the roots of his close-cropped hair. Then he

went very white and took a half-step toward the Arab. His fists were

clenched. Suddenly he thought better of whatever impulse was moving

him.

"Sergeant!"

he called. The non-commissioned officer hurried toward him, saluting

as his heels clicked together before his superior.

"Take

this black dog back to his people," he ordered. "See that

they leave at once. Shoot the first man who comes within range of

camp tonight."

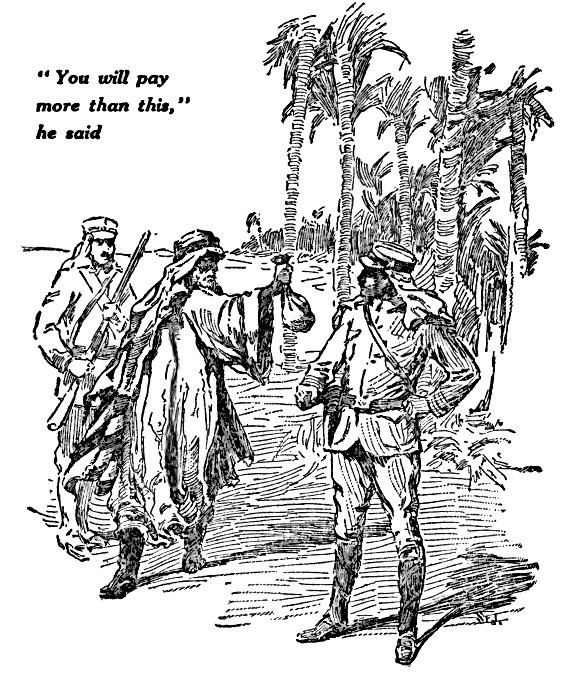

Sheik

Amor ben Khatour drew himself up to his full height. His evil eyes

narrowed. He raised the bag of gold level with the eyes of the French

officer.

"You

will pay more than this for the life of Achmet ben Houdin, my

sister's son," he said. "And as much again for the name

that you have called me and a hundred fold in sorrow in the bargain."

"Get

out of here!" growled Captain Armand Jacot, "before I kick

you out."

All

of this happened some three years before the opening of this tale.

The trail of Achmet ben Houdin and his accomplices is a matter of

record — you may verify it if you care to. He met the death he

deserved, and he met it with the stoicism of the Arab.

A

month later little Jeanne Jacot, the seven-year-old daughter of

Captain Armand Jacot, mysteriously disappeared. Neither the wealth of

her father and mother, or all the powerful resources of the great

republic were able to wrest the secret of her whereabouts from the

inscrutable desert that had swallowed her and her abductor.

A

reward of such enormous proportions was offered that many adventurers

were attracted to the hunt. This was no case for the modern detective

of civilization, yet several of these threw themselves into the

search — the bones of some are already bleaching beneath the

African sun upon the silent sands of the Sahara.

Two

Swedes, Carl Jenssen and Sven Malbihn, after three years of following

false leads at last gave up the search far to the south of the Sahara

to turn their attention to the more profitable business of ivory

poaching. In a great district they were already known for their

relentless cruelty and their greed for ivory. The natives feared and

hated them. The European governments in whose possessions they worked

had long sought them; but, working their way slowly out of the north

they had learned many things in the no-man's-land south of the Sahara

which gave them immunity from capture through easy avenues of escape

that were unknown to those who pursued them. Their raids were sudden

and swift. They seized ivory and retreated into the trackless wastes

of the north before the guardians of the territory they raped could

be made aware of their presence. Relentlessly they slaughtered

elephants themselves as well as stealing ivory from the natives.

Their following consisted of a hundred or more renegade Arabs and

Negro slaves — a fierce, relentless band of cut-throats. Remember

them — Carl Jenssen and Sven Malbihn, yellow-bearded, Swedish

giants — for you will meet them later.

In

the heart of the jungle, hidden away upon the banks of a small

unexplored tributary of a large river that empties into the Atlantic

not so far from the equator, lay a small, heavily palisaded village.

Twenty palm-thatched, beehive huts sheltered its black population,

while a half-dozen goat skin tents in the center of the clearing

housed the score of Arabs who found shelter here while, by trading

and raiding, they collected the cargoes which their ships of the

desert bore northward twice each year to the market of Timbuktu.

Playing

before one of the Arab tents was a little girl of ten — a

black-haired, black-eyed little girl who, with her nut-brown skin and

graceful carriage looked every inch a daughter of the desert. Her

little fingers were busily engaged in fashioning a skirt of grasses

for a much-disheveled doll which a kindly disposed slave had made for

her a year or two before. The head of the doll was rudely chipped

from ivory, while the body was a rat skin stuffed with grass. The

arms and legs were bits of wood, perforated at one end and sewn to

the rat skin torso. The doll was quite hideous and altogether

disreputable and soiled, but Meriem thought it the most beautiful and

adorable thing in the whole world, which is not so strange in view of

the fact that it was the only object within that world upon which she

might bestow her confidence and her love.

Everyone

else with whom Meriem came in contact was, almost without exception,

either indifferent to her or cruel. There was, for example, the old

black hag who looked after her, Mabunu — toothless, filthy and ill

tempered. She lost no opportunity to cuff the little girl, or even

inflict minor tortures upon her, such as pinching, or, as she had

twice done, searing the tender flesh with hot coals. And there was

The Sheik, her father. She feared him more than she did Mabunu. He

often scolded her for nothing, quite habitually terminating his

tirades by cruelly beating her, until her little body was black and

blue.

But

when she was alone she was happy, playing with Geeka, or decking her

hair with wild flowers, or making ropes of grasses. She was always

busy and always singing — when they left her alone. No amount of

cruelty appeared sufficient to crush the innate happiness and

sweetness from her full little heart. Only when The Sheik was near

was she quiet and subdued. Him she feared with a fear that was at

times almost hysterical terror. She feared the gloomy jungle too —

the cruel jungle that surrounded the little village with chattering

monkeys and screaming birds by day and the roaring and coughing and

moaning of the carnivora by night. Yes, she feared the jungle; but so

much more did she fear The Sheik that many times it was in her

childish head to run away, out into the terrible jungle forever

rather than longer to face the ever present terror of her father.

As

she sat there this day before The Sheik's goatskin tent, fashioning a

skirt of grasses for Geeka, The Sheik appeared suddenly approaching.

Instantly the look of happiness faded from the child's face. She

shrunk aside in an attempt to scramble from the path of the

leathern-faced old Arab; but she was not quick enough. With a brutal

kick the man sent her sprawling upon her face, where she lay quite

still, tearless but trembling. Then, with an oath at her, the man

passed into the tent. The old, black hag shook with appreciative

laughter, disclosing an occasional and lonesome yellow fang.

When

she was sure The Sheik had gone, the little girl crawled to the shady

side of the tent, where she lay quite still, hugging Geeka close to

her breast, her little form racked at long intervals with choking

sobs. She dared not cry aloud, since that would have brought The

Sheik upon her again. The anguish in her little heart was not alone

the anguish of physical pain; but that infinitely more pathetic

anguish — of love denied a childish heart that yearns for love.

Little

Meriem could scarce recall any other existence than that of the stern

cruelty of The Sheik and Mabunu. Dimly, in the back of her childish

memory there lurked a blurred recollection of a gentle mother; but

Meriem was not sure but that even this was but a dream picture

induced by her own desire for the caresses she never received, but

which she lavished upon the much loved Geeka. Never was such a

spoiled child as Geeka. Its little mother, far from fashioning her

own conduct after the example set her by her father and nurse, went

to the extreme of indulgence. Geeka was kissed a thousand times a

day. There was play in which Geeka was naughty; but the little mother

never punished. Instead, she caressed and fondled; her attitude

influenced solely by her own pathetic desire for love.

Now,

as she pressed Geeka close to her, her sobs lessened gradually, until

she was able to control her voice, and pour out her misery into the

ivory ear of her only confidante.

"Geeka

loves Meriem," she whispered. "Why does The Sheik, my

father, not love me, too? Am I so naughty? I try to be good; but I

never know why he strikes me, so I cannot tell what I have done which

displeases him. Just now he kicked me and hurt me so, Geeka; but I

was only sitting before the tent making a skirt for you. That must be

wicked, or he would not have kicked me for it. But why is it wicked,

Geeka? Oh dear! I do not know, I do not know. I wish, Geeka, that I

were dead. Yesterday the hunters brought in the body of El Adrea. El

Adrea was quite dead. No more will he slink silently upon his

unsuspecting prey. No more will his great head and his maned

shoulders strike terror to the hearts of the grass eaters at the

drinking ford by night. No more will his thundering roar shake the

ground. El Adrea is dead. They beat his body terribly when it was

brought into the village; but El Adrea did not mind. He did not feel

the blows, for he was dead. When I am dead, Geeka, neither shall I

feel the blows of Mabunu, or the kicks of The Sheik, my father. Then

shall I be happy. Oh, Geeka, how I wish that I were dead!"

If

Geeka contemplated a remonstrance it was cut short by sounds of

altercation beyond the village gates. Meriem listened. With the

curiosity of childhood she would have liked to have run down there

and learn what it was that caused the men to talk so loudly. Others

of the village were already trooping in the direction of the noise.

But Meriem did not dare. The Sheik would be there, doubtless, and if

he saw her it would be but another opportunity to abuse her, so

Meriem lay still and listened.

Presently

she heard the crowd moving up the street toward The Sheik's tent.

Cautiously she stuck her little head around the edge of the tent. She

could not resist the temptation, for the sameness of the village life

was monotonous, and she craved diversion. What she saw was two

strangers — white men. They were alone, but as they approached she

learned from the talk of the natives that surrounded them that they

possessed a considerable following that was camped outside the

village. They were coming to palaver with The Sheik.

The

old Arab met them at the entrance to his tent. His eyes narrowed

wickedly when they had appraised the newcomers. They stopped before

him, exchanging greetings. They had come to trade for ivory they

said. The Sheik grunted. He had no ivory. Meriem gasped. She knew

that in a near-by hut the great tusks were piled almost to the roof.

She poked her little head further forward to get a better view of the

strangers. How white their skins! How yellow their great beards!

Suddenly

one of them turned his eyes in her direction. She tried to dodge back

out of sight, for she feared all men; but he saw her. Meriem noticed

the look of almost shocked surprise that crossed his face. The Sheik

saw it too, and guessed the cause of it.

"I

have no ivory," he repeated. "I do not wish to trade. Go

away. Go now."

He

stepped from his tent and almost pushed the strangers about in the

direction of the gates. They demurred, and then The Sheik threatened.

It would have been suicide to have disobeyed, so the two men turned

and left the village, making their way immediately to their own camp.

The

Sheik returned to his tent; but he did not enter it. Instead he

walked to the side where little Meriem lay close to the goat skin

wall, very frightened. The Sheik stooped and clutched her by the arm.

Viciously he jerked her to her feet, dragged her to the entrance of

the tent, and shoved her viciously within. Following her he again

seized her, beating her ruthlessly.

"Stay

within!" he growled. "Never let the strangers see thy face.

Next time you show yourself to strangers I shall kill you!"

With

a final vicious cuff he knocked the child into a far corner of the

tent, where she lay stifling her moans, while The Sheik paced to and

fro muttering to himself. At the entrance sat Mabunu, muttering and

chuckling.

In

the camp of the strangers one was speaking rapidly to the other.

"There

is no doubt of it, Malbihn," he was saying. "Not the

slightest; but why the old scoundrel hasn't claimed the reward long

since is what puzzles me."

"There

are some things dearer to an Arab, Jenssen, than money,"

returned the first speaker — "revenge is one of them."

"Anyhow

it will not harm to try the power of gold," replied Jenssen.

Malbihn

shrugged.

"Not

on The Sheik," he said. "We might try it on one of his

people; but The Sheik will not part with his revenge for gold. To

offer it to him would only confirm his suspicions that we must have

awakened when we were talking to him before his tent. If we got away

with our lives, then, we should be fortunate."

"Well,

try bribery, then," assented Jenssen.

But

bribery failed — grewsomely. The tool they selected after a stay of

several days in their camp outside the village was a tall, old

headman of The Sheik's native contingent. He fell to the lure of the

shining metal, for he had lived upon the coast and knew the power of

gold. He promised to bring them what they craved, late that night.

Immediately

after dark the two white men commenced to make arrangements to break

camp. By midnight all was prepared. The porters lay beside their

loads, ready to swing them aloft at a moment's notice. The armed

askaris loitered between the balance of the safari and the Arab

village, ready to form a rear guard for the retreat that was to begin

the moment that the head man brought that which the white masters

awaited.

Presently

there came the sound of footsteps along the path from the village.

Instantly the askaris and the whites were on the alert. More than a

single man was approaching. Jenssen stepped forward and challenged

the newcomers in a low whisper.

"Who

comes?" he queried.

"Mbeeda,"

came the reply.

Mbeeda

was the name of the traitorous head man. Jenssen was satisfied,

though he wondered why Mbeeda had brought others with him. Presently

he understood. The thing they fetched lay upon a litter borne by two

men. Jenssen cursed beneath his breath. Could the fool be bringing

them a corpse? They had paid for a living prize!

The

bearers came to a halt before the white men.

"This

has your gold purchased," said one of the two. They set the

litter down, turned and vanished into the darkness toward the

village. Malbihn looked at Jenssen, a crooked smile twisting his

lips. The thing upon the litter was covered with a piece of cloth.

"Well?"

queried the latter. "Raise the covering and see what you have

bought. Much money shall we realize on a corpse — especially after

the six months beneath the burning sun that will be consumed in

carrying it to its destination!"

"The

fool should have known that we desired her alive," grumbled

Malbihn, grasping a corner of the cloth and jerking the cover from

the thing that lay upon the litter.

At

sight of what lay beneath both men stepped back — involuntary oaths

upon their lips — for there before them lay the dead body of

Mbeeda, the faithless head man.

Five

minutes later the safari of Jenssen and Malbihn was forcing its way

rapidly toward the west, nervous askaris guarding the rear from the

attack they momentarily expected.

|