III

s

the trainer, with raised lash, hesitated an instant at the entrance

to the box where the boy and the ape confronted him, a tall

broad-shouldered man pushed past him and entered. As his eyes fell

upon the newcomer a slight flush mounted the boy's cheeks. s

the trainer, with raised lash, hesitated an instant at the entrance

to the box where the boy and the ape confronted him, a tall

broad-shouldered man pushed past him and entered. As his eyes fell

upon the newcomer a slight flush mounted the boy's cheeks.

"Father!"

he exclaimed.

The

ape gave one look at the English lord, and then leaped toward him,

calling out in excited jabbering. The man, his eyes going wide in

astonishment, stopped as though turned to stone.

"Akut!"

he cried.

The

boy looked, bewildered, from the ape to his father, and from his

father to the ape. The trainer's jaw dropped as he listened to what

followed, for from the lips of the Englishman flowed the gutturals of

an ape that were answered in kind by the huge anthropoid that now

clung to him.

And

from the wings a hideously bent and disfigured old man watched the

tableau in the box, his pock-marked features working spasmodically in

varying expressions that might have marked every sensation in the

gamut from pleasure to terror.

"Long

have I looked for you, Tarzan," said Akut. "Now that I have

found you I shall come to your jungle and live there always."

The

man stroked the beast's head. Through his mind there was running

rapidly a train of recollection that carried him far into the depths

of the primeval African forest where this huge, man-like beast had

fought shoulder to shoulder with him years before. He saw the black

Mugambi wielding his deadly knob-stick, and beside them, with bared

fangs and bristling whiskers, Sheeta the terrible; and pressing close

behind the savage and the savage panther, the hideous apes of Akut.

The man sighed. Strong within him surged the jungle lust that he had

thought dead. Ah! if he could go back even for a brief month of it,

to feel again the brush of leafy branches against his naked hide; to

smell the musty rot of dead vegetation — frankincense and myrrh to

the jungle born; to sense the noiseless coming of the great carnivora

upon his trail; to hunt and to be hunted; to kill! The picture was

alluring. And then came another picture — a sweet-faced woman,

still young and beautiful; friends; a home; a son. He shrugged his

giant shoulders.

"It

cannot be, Akut," he said; "but if you would return, I

shall see that it is done. You could not be happy here — I may not

be happy there."

The

trainer stepped forward. The ape bared his fangs, growling.

"Go

with him, Akut," said Tarzan of the Apes. "I will come and

see you tomorrow."

The

beast moved sullenly to the trainer's side. The latter, at John

Clayton's request, told where they might be found. Tarzan turned

toward his son.

"Come!"

he said, and the two left the theater. Neither spoke for several

minutes after they had entered the limousine. It was the boy who

broke the silence.

"The

ape knew you," he said, "and you spoke together in the

ape's tongue. How did the ape know you, and how did you learn his

language?"

And

then, briefly and for the first time, Tarzan of the Apes told his son

of his early life — of the birth in the jungle, of the death of his

parents, and of how Kala, the great she ape had suckled and raised

him from infancy almost to manhood. He told him, too, of the dangers

and the horrors of the jungle; of the great beasts that stalked one

by day and by night; of the periods of drought, and of the

cataclysmic rains; of hunger; of cold; of intense heat; of nakedness

and fear and suffering. He told him of all those things that seem

most horrible to the creature of civilization in the hope that the

knowledge of them might expunge from the lad's mind any inherent

desire for the jungle. Yet they were the very things that made the

memory of the jungle what it was to Tarzan — that made up the

composite jungle life he loved. And in the telling he forgot one

thing — the principal thing — that the boy at his side, listening

with eager ears, was the son of Tarzan of the Apes.

After

the boy had been tucked away in bed — and without the threatened

punishment — John Clayton told his wife of the events of the

evening, and that he had at last acquainted the boy with the facts of

his jungle life. The mother, who had long foreseen that her son must

some time know of those frightful years during which his father had

roamed the jungle, a naked, savage beast of prey, only shook her

head, hoping against hope that the lure she knew was still strong in

the father's breast had not been transmitted to his son.

Tarzan

visited Akut the following day, but though Jack begged to be allowed

to accompany him he was refused. This time Tarzan saw the pock-marked

old owner of the ape, whom he did not recognize as the wily Paulvitch

of former days. Tarzan, influenced by Akut's pleadings, broached the

question of the ape's purchase; but Paulvitch would not name any

price, saying that he would consider the matter.

When

Tarzan returned home Jack was all excitement to hear the details of

his visit, and finally suggested that his father buy the ape and

bring it home. Lady Greystoke was horrified at the suggestion. The

boy was insistent. Tarzan explained that he had wished to purchase

Akut and return him to his jungle home, and to this the mother

assented. Jack asked to be allowed to visit the ape, but again he was

met with flat refusal. He had the address, however, which the trainer

had given his father, and two days later he found the opportunity to

elude his new tutor — who had replaced the terrified Mr. Moore —

and after a considerable search through a section of London which he

had never before visited, he found the smelly little quarters of the

pock-marked old man. The old fellow himself replied to his knocking,

and when he stated that he had come to see Ajax, opened the door and

admitted him to the little room which he and the great ape occupied.

In former years Paulvitch had been a fastidious scoundrel; but ten

years of hideous life among the cannibals of Africa had eradicated

the last vestige of niceness from his habits. His apparel was

wrinkled and soiled. His hands were unwashed, his few straggling

locks uncombed. His room was a jumble of filthy disorder. As the boy

entered he saw the great ape squatting upon the bed, the coverlets of

which were a tangled wad of filthy blankets and ill-smelling quilts.

At sight of the youth the ape leaped to the floor and shuffled

forward. The man, not recognizing his visitor and fearing that the

ape meant mischief, stepped between them, ordering the ape back to

the bed.

"He

will not hurt me," cried the boy. "We are friends, and

before, he was my father's friend. They knew one another in the

jungle. My father is Lord Greystoke. He does not know that I have

come here. My mother forbid my coming; but I wished to see Ajax, and

I will pay you if you will let me come here often and see him."

At

the mention of the boy's identity Paulvitch's eyes narrowed. Since he

had first seen Tarzan again from the wings of the theater there had

been forming in his deadened brain the beginnings of a desire for

revenge. It is a characteristic of the weak and criminal to attribute

to others the misfortunes that are the result of their own

wickedness, and so now it was that Alexis Paulvitch was slowly

recalling the events of his past life and as he did so laying at the

door of the man whom he and Rokoff had so assiduously attempted to

ruin and murder all the misfortunes that had befallen him in the

failure of their various schemes against their intended victim.

He

saw at first no way in which he could, with safety to himself, wreak

vengeance upon Tarzan through the medium of Tarzan's son; but that

great possibilities for revenge lay in the boy was apparent to him,

and so he determined to cultivate the lad in the hope that fate would

play into his hands in some way in the future. He told the boy all

that he knew of his father's past life in the jungle and when he

found that the boy had been kept in ignorance of all these things for

so many years, and that he had been forbidden visiting the zoological

gardens; that he had had to bind and gag his tutor to find an

opportunity to come to the music hall and see Ajax, he guessed

immediately the nature of the great fear that lay in the hearts of

the boy's parents — that he might crave the jungle as his father

had craved it.

And

so Paulvitch encouraged the boy to come and see him often, and always

he played upon the lad's craving for tales of the savage world with

which Paulvitch was all too familiar. He left him alone with Akut

much, and it was not long until he was surprised to learn that the

boy could make the great beast understand him — that he had

actually learned many of the words of the primitive language of the

anthropoids.

During

this period Tarzan came several times to visit Paulvitch. He seemed

anxious to purchase Ajax, and at last he told the man frankly that he

was prompted not only by a desire upon his part to return the beast

to the liberty of his native jungle; but also because his wife feared

that in some way her son might learn the whereabouts of the ape and

through his attachment for the beast become imbued with the roving

instinct which, as Tarzan explained to Paulvitch, had so influenced

his own life.

The

Russian could scarce repress a smile as he listened to Lord

Greystoke's words, since scarce a half hour had passed since the time

the future Lord Greystoke had been sitting upon the disordered bed

jabbering away to Ajax with all the fluency of a born ape.

It

was during this interview that a plan occurred to Paulvitch, and as a

result of it he agreed to accept a certain fabulous sum for the ape,

and upon receipt of the money to deliver the beast to a vessel that

was sailing south from Dover for Africa two days later. He had a

double purpose in accepting Clayton's offer. Primarily, the money

consideration influenced him strongly, as the ape was no longer a

source of revenue to him, having consistently refused to perform upon

the stage after having discovered Tarzan. It was as though the beast

had suffered himself to be brought from his jungle home and exhibited

before thousands of curious spectators for the sole purpose of

searching out his long lost friend and master, and, having found him,

considered further mingling with the common herd of humans

unnecessary. However that may be, the fact remained that no amount of

persuasion could influence him even to show himself upon the music

hall stage, and upon the single occasion that the trainer attempted

force the results were such that the unfortunate man considered

himself lucky to have escaped with his life. All that saved him was

the accidental presence of Jack Clayton, who had been permitted to

visit the animal in the dressing room reserved for him at the music

hall, and had immediately interfered when he saw that the savage

beast meant serious mischief.

And

after the money consideration, strong in the heart of the Russian was

the desire for revenge, which had been growing with constant brooding

over the failures and miseries of his life, which he attributed to

Tarzan; the latest, and by no means the least, of which was Ajax's

refusal to longer earn money for him. The ape's refusal he traced

directly to Tarzan, finally convincing himself that the ape man had

instructed the great anthropoid to refuse to go upon the stage.

Paulvitch's

naturally malign disposition was aggravated by the weakening and

warping of his mental and physical faculties through torture and

privation. From cold, calculating, highly intelligent perversity it

had deteriorated into the indiscriminating, dangerous menace of the

mentally defective. His plan, however, was sufficiently cunning to at

least cast a doubt upon the assertion that his mentality was

wandering. It assured him first of the competence which Lord

Greystoke had promised to pay him for the deportation of the ape, and

then of revenge upon his benefactor through the son he idolized. That

part of his scheme was crude and brutal — it lacked the refinement

of torture that had marked the master strokes of the Paulvitch of

old, when he had worked with that virtuoso of villainy, Nikolas

Rokoff — but it at least assured Paulvitch of immunity from

responsibility, placing that upon the ape, who would thus also be

punished for his refusal longer to support the Russian.

Everything

played with fiendish unanimity into Paulvitch's hands. As chance

would have it, Tarzan's son overheard his father relating to the

boy's mother the steps he was taking to return Akut safely to his

jungle home, and having overheard he begged them to bring the ape

home that he might have him for a play-fellow. Tarzan would not have

been averse to this plan; but Lady Greystoke was horrified at the

very thought of it. Jack pleaded with his mother; but all

unavailingly. She was obdurate, and at last the lad appeared to

acquiesce in his mother's decision that the ape must be returned to

Africa and the boy to school, from which he had been absent on

vacation.

He

did not attempt to visit Paulvitch's room again that day, but instead

busied himself in other ways. He had always been well supplied with

money, so that when necessity demanded he had no difficulty in

collecting several hundred pounds. Some of this money he invested in

various strange purchases which he managed to smuggle into the house,

undetected, when he returned late in the afternoon.

The

next morning, after giving his father time to precede him and

conclude his business with Paulvitch, the lad hastened to the

Russian's room. Knowing nothing of the man's true character the boy

dared not take him fully into his confidence for fear that the old

fellow would not only refuse to aid him, but would report the whole

affair to his father. Instead, he simply asked permission to take

Ajax to Dover. He explained that it would relieve the old man of a

tiresome journey, as well as placing a number of pounds in his

pocket, for the lad purposed paying the Russian well.

"You

see," he went on, "there will be no danger of detection

since I am supposed to be leaving on an afternoon train for school.

Instead I will come here after they have left me on board the train.

Then I can take Ajax to Dover, you see, and arrive at school only a

day late. No one will be the wiser, no harm will be done, and I shall

have had an extra day with Ajax before I lose him forever."

The

plan fitted perfectly with that which Paulvitch had in mind. Had he

known what further the boy contemplated he would doubtless have

entirely abandoned his own scheme of revenge and aided the boy whole

heartedly in the consummation of the lad's, which would have been

better for Paulvitch, could he have but read the future but a few

short hours ahead.

That

afternoon Lord and Lady Greystoke bid their son good-bye and saw him

safely settled in a first-class compartment of the railway carriage

that would set him down at school in a few hours. No sooner had they

left him, however, than he gathered his bags together, descended from

the compartment and sought a cab stand outside the station. Here he

engaged a cabby to take him to the Russian's address. It was dusk

when he arrived. He found Paulvitch awaiting him. The man was pacing

the floor nervously. The ape was tied with a stout cord to the bed.

It was the first time that Jack had ever seen Ajax thus secured. He

looked questioningly at Paulvitch. The man, mumbling, explained that

he believed the animal had guessed that he was to be sent away and he

feared he would attempt to escape.

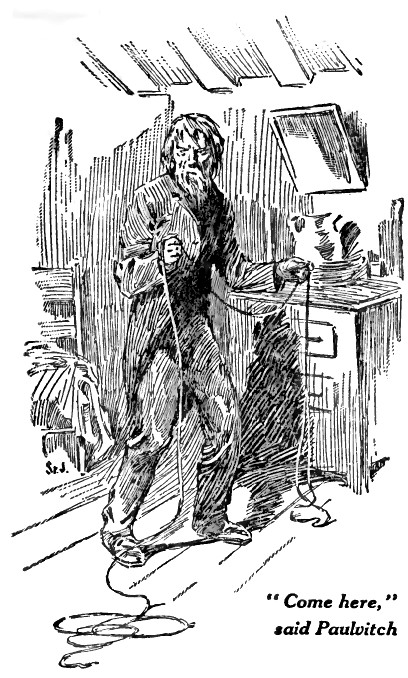

Paulvitch

carried another piece of cord in his hand. There was a noose in one

end of it which he was continually playing with. He walked back and

forth, up and down the room. His pock-marked features were working

horribly as he talked silent to himself. The boy had never seen him

thus — it made him uneasy. At last Paulvitch stopped on the

opposite side of the room, far from the ape.

"Come

here," he said to the lad. "I will show you how to secure

the ape should he show signs of rebellion during the trip."

The

lad laughed. "It will not be necessary," he replied. "Ajax

will do whatever I tell him to do."

The

old man stamped his foot angrily. "Come here, as I tell you,"

he repeated. "If you do not do as I say you shall not accompany

the ape to Dover — I will take no chances upon his escaping."

Still

smiling, the lad crossed the room and stood before the Russ.

"Turn

around, with your back toward me," directed the latter, "that

I may show you how to bind him quickly."

The

boy did as he was bid, placing his hands behind him when Paulvitch

told him to do so. Instantly the old man slipped the running noose

over one of the lad's wrists, took a couple of half hitches about his

other wrist, and knotted the cord.

The

moment that the boy was secured the attitude of the man changed. With

an angry oath he wheeled his prisoner about, tripped him and hurled

him violently to the floor, leaping upon his breast as he fell. From

the bed the ape growled and struggled with his bonds. The boy did not

cry out — a trait inherited from his savage sire whom long years in

the jungle following the death of his foster mother, Kala the great

ape, had taught that there was none to come to the succor of the

fallen.

Paulvitch's

fingers sought the lad's throat. He grinned down horribly into the

face of his victim.

"Your

father ruined me," he mumbled. "This will pay him. He will

think that the ape did it. I will tell him that the ape did it. That

I left him alone for a few minutes, and that you sneaked in and the

ape killed you. I will throw your body upon the bed after I have

choked the life from you, and when I bring your father he will see

the ape squatting over it," and the twisted fiend cackled in

gloating laughter. His fingers closed upon the boy's throat.

Behind

them the growling of the maddened beast reverberated against the

walls of the little room. The boy paled, but no other sign of fear or

panic showed upon his countenance. He was the son of Tarzan. The

fingers tightened their grip upon his throat. It was with difficulty

that he breathed, gaspingly. The ape lunged against the stout cord

that held him. Turning, he wrapped the cord about his hands, as a man

might have done, and surged heavily backward. The great muscles stood

out beneath his shaggy hide. There was a rending as of splintered

wood — the cord held, but a portion of the footboard of the bed

came away.

At

the sound Paulvitch looked up. His hideous face went white with

terror — the ape was free.

With

a single bound the creature was upon him. The man shrieked. The brute

wrenched him from the body of the boy. Great fingers sunk into the

man's flesh. Yellow fangs gaped close to his throat — he struggled,

futilely — and when they closed, the soul of Alexis Paulvitch

passed into the keeping of the demons who had long been awaiting it.

The

boy struggled to his feet, assisted by Akut. For two hours under the

instructions of the former the ape worked upon the knots that secured

his friend's wrists. Finally they gave up their secret, and the boy

was free. Then he opened one of his bags and drew forth some

garments. His plans had been well made. He did not consult the beast,

which did all that he directed. Together they slunk from the house,

but no casual observer might have noted that one of them was an ape.

|