1

The Making of the

Ship

(a) EVOLUTION

THE earliest and

simplest means of water carriage employed by man consisted of the rafts or

floating logs, which have doubtless been used since the dawn of the human race

for carrying men and their property.

This early and crude form was supplemented by the

"dug-out," found in all parts of the world, and made from the

hollowed-out trunk of a tree. Later followed various forms of the canoe; often

a mere framework of bone or wooden ribs covered with hides or tree-bark. This

led to the conventional built-up boat, which still, however, remained of the open

or undecked type.

Decked craft are of

unknown antiquity; but it is certain that the ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians,

Greeks and Romans all possessed ships of this class, capable of transporting

large numbers of men, that these vessels were composed of keels, frames and

beams, and had decks and planking secured by fastenings of metal or wood, and

that they were also fitted with the conventional appliances for rowing,

sailing, steering and anchoring.

In B.C. 350 the

Greeks are known to have possessed a navy and dockyards, and from this time

forward, throughout the Mediterranean, great progress was made in maritime

affairs with regard to the transportation by ships both of men and goods.

The Phoenicians

were the first to construct warships (of the "galley" type) about 900

B.C., propulsion being effected by two banks of oars. The Greeks later employed

oars arranged in several banks, and rising in tiers one above the other, a type

which existed among the Mediterranean nations for ships (both of War and State)

until well into the middle ages.

The later merchant

ships of the Western Mediterranean nations in general did not differ greatly

from the warships of the time, although there seems to be more distinction of

this kind among those of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

As all the early

battles must have taken place at close quarters, or at least at a range

suitable for the bow and arrow, a demand at once grew up for the lofty

castellated structures which adorned the prows and sterns of 'most mediaeval

ships; a form which, with some modifications, survived well into the nineteenth

century,' and still leaves its traces in the modern appellation which is given

to the crew's quarters in the fo'csle or fore-castle.

The art of

shipbuilding progressed very slowly for centuries, the transition from type to

type being but gradual. In the seventeenth century the national characteristics

of build were but slightly marked; all the vessels of that time having the

following features in common, which have since disappeared: a lofty and often

highly decorated stern; a square sail hung forward below the bowsprit; and a

diminutive lateen sail on the mizzen mast, doubtless intended as an aid in

steering, and Which survives to-day in the common "yawl" rig.

During this period

the armament was increased, in order to give a heavier broadside, and the ships

proportionately increased in beam. This heavier type may be said to have

endured well into the last century, with such modification as the development

of the arts and sciences had then brought about.

The use of iron for the construction of a ship was

tried in a small craft as early as 1787, but the first iron ship (of any

magnitude) to be built was the paddle steamer Aaron

Manby, in 1821. The practical establishment of iron shipbuilding

dates, however, from a few years later, When John Laird, of Birkenhead, in

1829, first made a commercial success of iron ship-construction. The Sirius, in 1837, was the first iron vessel

classed at "Lloyd's"; but this innovation was generally opposed until

almost the middle of the century, when this method of construction first met

with unqualified favour.

The adapting of the

steam-engine to all classes of ships, and the employment of steel instead of

iron in the construction of the hull have, to a yet further extent,

revolutionised the world's mercantile marine. The substitution of mild steel as

a substitute for iron — an invention originally introduced into this country

from France — is now thoroughly established, and has resulted in producing a class

of ships which, ton for ton, are not only stronger and more durable than

vessels of wood, or even vessels of iron, but are actually proved to be 50 per

cent. lighter than boats built of timber, and 15 per cent. lighter than

iron-built ships.

Finally, the now

established practice of sub-dividing these steel-built vessels into watertight

compartments (which can be used at will for water-ballast) has still further

diminished the chances of lives being lost in the event of a wreck or a

collision.

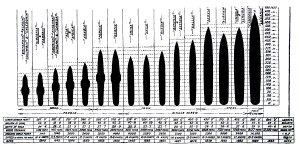

[CLICK THE IMAGE ABOVE TO SEE A LARGE RENDERING

OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE SHIP CHART]

(b) RELATIVE SIZE

AND GROWTH OF MERCANTILE STEAMSHIPS

In the last sixty

years the duration of the Transatlantic voyage has been reduced by more than 50

per cent., the size of the ships has been multiplied by fifteen, and their

power and carrying capacity by more than fifty. Enormous strides have been made

in shipbuilding and in increasing the size of ocean steamships.

|

Year Built.

|

Vessel.

|

Length Feet.

|

Beam Feet.

|

H. P.

|

Tonnage.

|

|

1840

|

Acadia

|

228

|

34

|

425

|

1,150

|

|

1850

|

Atlantic

|

276

|

45

|

850

|

2,800

|

|

1855

|

Persia

|

300

|

45

|

900

|

8,300

|

|

1862

|

Scotia

|

379

|

47

|

1,000

|

8,871

|

|

1881

|

City of Rome

|

560

|

52

|

17,500

|

8,144

|

|

1885

|

Umbria

|

520

|

57

|

15,000

|

8,128

|

|

1889

|

Teutonic

|

582

|

57

|

17,000

|

9,685

|

|

1889

|

City of Paris

|

527

|

63

|

18,000

|

10,499

|

|

1893

|

Campania

|

625

|

65

|

25,000

|

13,000

|

|

1897

|

Kaiser Wilhelm der

Grosse

|

649

|

66

|

27,000

|

13,800

|

|

1899

|

Oceanic

|

705

|

68

|

30,000

|

17,040

|

|

1900

|

Deutschland

|

662

|

67

|

30,000

|

16,502

|

|

1901

|

Kron Prinz Wm.

|

630

|

|

30,000

|

15,000

|

|

1901

|

Celtic

|

700

|

75

|

14,000

|

20,904

|

|

1902

|

Kaiser Wm. d. II

|

706

|

|

38,000

|

19,500

|

|

1902

|

Cedric

|

700

|

75

|

|

21,000

|

(c) CONSUMPTION OF

COAL

The consumption of coal in steamships has

(proportionately) much decreased since the introduction of the compound engine.

Previous to that time a vessel fitted with the best type of engines, such as

the Scotia, of the Cunard line —

which was floated in 1862, and had a midship section of 841 square feet —

consumed 160 tons of coal per day, or 1,600 tons on the passage between New

York and Liverpool. The City of Brussels,

a screw-steamer of the Inman line, floated in 1869, with a midship section of

909 square feet, consumed 95 tons per day; while the Spain, a screw-steamer of the National line, launched in

1871, with compound machinery, and at that time the longest vessel on the

Atlantic — with a length of 425 feet 6 inches on the load-line, beam-mould 43

feet, draught (loaded) 24 feet 9 inches — when making the passage in September

of the above year, consumed only 53 tons per day, or 500 tons on the run. All

these three vessels had a similar average of speed. There are still later

instances where but 40 tons of coal per day were used.

Ocean steamers are

large consumers of coal. The Orient line, with their fleet of ships running

from England to Australia every two weeks, may be instanced. The steamship

Austral went from London to Sydney in 35 days, and consumed on the voyage 3,641

tons of coal; her coal bunkers held 2,750 tons. The steamship Oregon consumed over 330 tons per day on

the passage from Liverpool to New York; her bunkers held nearly 4,000 tons. The

Stirling Castle brought home in

one cargo 2,200 tons of tea, and consumed 2,800 tons of coal in doing so.

Immense stocks of coal are kept at various coaling stations — St. Vincent,

Madeira, Port Said, Singapore, and elsewhere; the reserve at the latter place

being about 20,000 tons.

The Oceanic consumes from 400 tons to 500 tons

of coal per day, the Majestic and

Teutonic about 150 tons less.

An enormous

increase in coal consumption is necessary for a comparatively slight increase

in the vessel's speed. Suppose the propellers were turning 57 times to the

minute, and it was desired to make them turn 58. It would require the burning

of five additional tons of coal a day. The coal burned varies as the cube of

the speed attained. If the vessel could be driven 12 knots an hour by burning

90 tons of coal a day, by burning twice that amount (180 tons) her speed is

advanced to 16 knots, a gain of only one-third. Increase the coal to 300 tons a

day, the rate of gain is even less, the speed being 20 knots. It is estimated

that if the present horsepower could be doubled by extra furnaces and firemen

and the burning of sufficient coal, the result would be to shorten her time

across the Atlantic by a bare half day only. So enormous is the cost of the

gain of an hour's time to an Atlantic "greyhound."

GALLEON OF COLUMBUS (HENRY THE SEVENTH'S DAY)

GALLEON OF COLUMBUS (HENRY THE SEVENTH'S DAY)

(d) THE DESIGN AND

CONSTRUCTION OF SHIPS

The earliest ship

builders gave little thought or care to the design or construction of the hull,

but devoted their attention rather to the interior arrangements and the upper

works of their vessels. The reason for this was that the factors of speed and

capacity in relation to size were then less paramount than at present.

During the middle

ages the purely decorative features or what is called the "top

hamper," were extravagantly increased, but with due regard for stability

and strength these gradually gave way to more serviceable plans and models,

until at the latter part of the eighteenth century, the types of our sailing

craft first began to approach the forms with which we are now familiar.

Certain accepted

rules and formulae were eventually laid down which, without restricting

shipbuilders to any very definite dimensions, enforced due regard for the rules

of proportion and measurement which had proved suitable or satisfactory in

practice — thus meeting the special demands that were likely to be made upon

the various types of craft, whether war vessels or merchantmen, under the more

stringent modern conditions.

When all ships were

of small size, the masts usually consisted of a single piece or

"stick," but the modern sailing vessel of large dimensions (1,500 to

3,000 tons) has its masts of steel, or made up of smaller pieces of timber

strapped or bound together with steel bands; while the required height is

obtained by constructing them in two or more lengths, the one standing above

the other. Top masts, top gallant masts and "royals," are each formed

of one stick surmounting another. The bow-sprit is also usually formed of a

single stick.

The earliest sails

in our northern latitudes were probably made from the skins of animals; but in

the tropics large palm-leaves, at first singly, and later more or less roughly

fastened together, have been used since time immemorial. Later still, the sails

of all races seem to have consisted of woven fabrics, constructed from the

sterns of certain plants (e.g. flax) or grasses. These primitive sails,

moreover, were generally of a more or less square (lug-sail) shape. These,

however, were followed by the more simple fore and aft lateen rig, the latest

development of which is the lateen sail still used on small craft in the

Mediterranean.

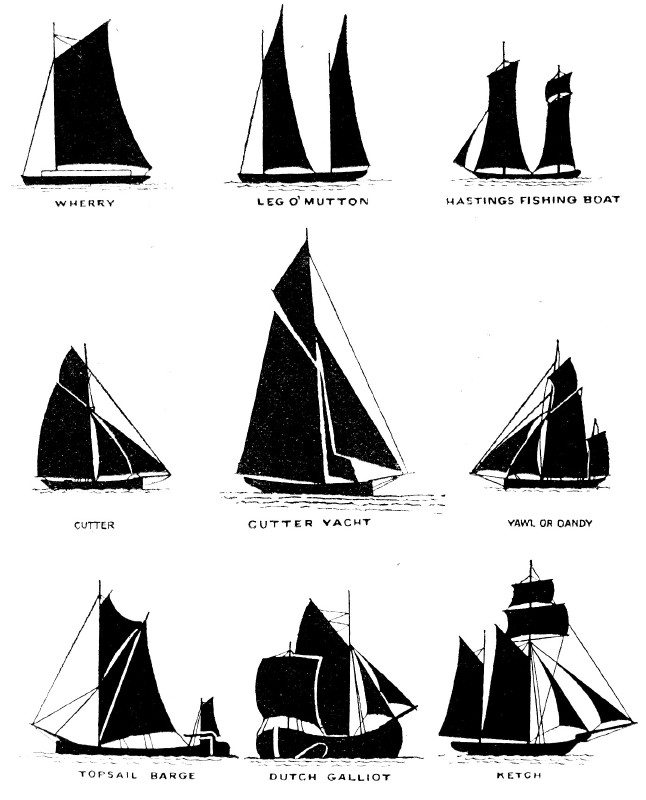

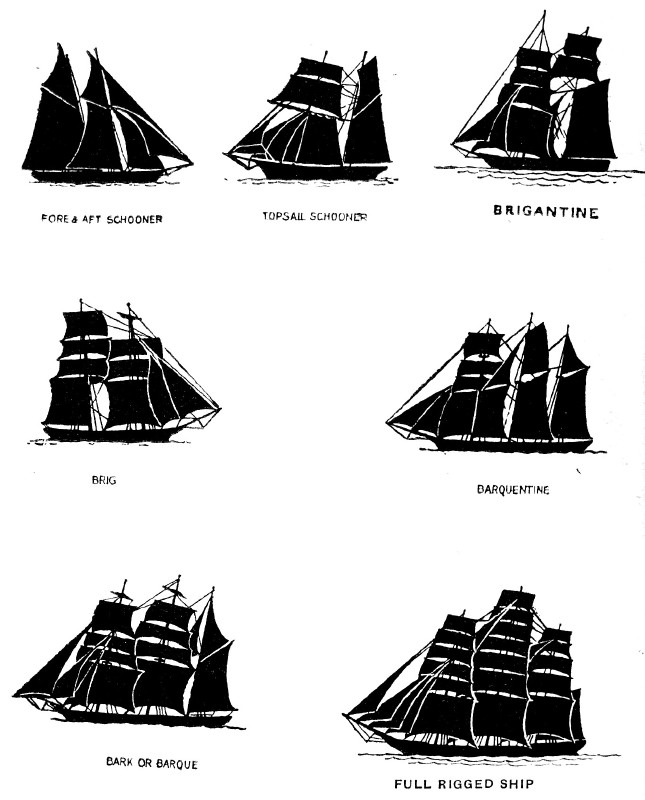

In a modern rigged

vessel sail is reduced firstly by the division of the total sail-area into

small sails of manageable shape and dimensions; so that they may be taken in

one after the other as occasion requires, and secondly by "reefing,"

an arrangement which allows of a portion of individual sail only being furled

at a time. Numerous devices for furling sails have been used to accomplish

this from time to time, but the usual course is to employ several rows of

"reef-points " or short ropes attached to the sail itself, by means

of which it can be fastened down to the yard to which it is attached, thereby

effectively reducing the area, but still allowing a portion of the sail to

remain in position.

Rigging is divided

into two classes, the "standing rigging," by which the masts and

spars are supported, and "running rigging," by which the sails

themselves are manipulated or trimmed. Modern improvements and developments

with regard to rigging consist chiefly in the substitution of wire rope in

place of the Manila or hemp rope formerly used.

The question of

ballast has always been a serious one for sea captains making long voyages in

sailing vessels. Water ballast is used on large ocean steamers, and many of the

modern sailing craft have tanks arranged in their holds, so that they can take

on water ballast direct from the sea. But the old-time sailing vessels have to

wait to see what ballast they can pick up before making the homeward trip. The

most common ballast is stone or rock, and the relative value of its grades is

known to every shipmaster, who can often dispose of such a cargo for more than

the cost of loading and unloading, Sand and common dirt are also shipped in

ballast.

Of late there has

been much speculation as to the life of a ship. This is of course a question

that depends very much upon the builders. It is found that Norwegian vessels

have a life of 30 years; Italian, 27; British, 26; German, 25; Dutch, 22;

French, 20; United States, 18. The average death-rate of the world's shipping

is about 4 per cent. and the birth-rate 5 per cent.

The largest cargo

carrier is, at present, the White Star steamer Celtic.

She is 20,880 tons gross measurement, and her dimensions are: over-all length,

700 feet; beam, 75 feet; depth, 49 feet.

The Pennsylvania, of the Hamburg American

Line, is the next largest cargo carrier, being rated at 20,000 tons burden.

Four steamships of

enormous dimensions are projected (two of which are already laid down in

Connecticut, U.S.) for the Great Northern Steamship Co.'s Pacific Service. They

are to be of 21,000 R.T.

The largest tank

steamer is the St. Helens, which

is built to carry 2,850,000 gallons of oil in bulk.

The largest

schooner in existence is a seven-masted schooner (building in Maine, U.S.A.).

It is 310 feet long on the keel, 345 feet over all, and will register about

2,750 tons net, with an estimated coal-carrying capacity of from 5,000 to 5,500

tons.

The largest sailing

ship afloat is called the Potosi.

She was built at Bremen, with five masts, is 394 feet long, 50 feet beam, with

a draught of 25 feet and a carrying capacity of 6,150 tons.

The second largest

ship in the world is the five-masted French ship France: length, 3I6 feet; beam, 49 feet; depth, 26 feet. She

has a net tonnage of 3,624, a sail area of 49,000 square feet, and has carried

a cargo of 5,900 tons. The British ship Liverpool,

3,330 tons, is 333 feet long, 48 feet broad, and 28 feet deep. The Palgrave is of 3,078 tons. She has taken

20,000 bales of jute from Calcutta to Dundee in a single voyage.

The biggest of

wooden ships is the Roanoke,

built by Arthur Sewall and Co. Her dimensions are: length of keel, 300 feet;

length over all, 350 feet; height of foremast top from deck, 180 feet; length

of main yard, 95 feet; main lower topsail yard, 86 feet; main upper topsail

yard, 77 feet; main top-gallant yard, 66 feet; main royal yard, 55 feet; main

skysail yard, 44 feet; bowsprit, 65 feet; deck to keelson, 22.2 feet; keelson to

bottom, 12 feet; height of keelson, 9 feet 8 inches. With all sails set she

spreads 15,000 square yards of canvas. She has four masts — fore, main, mizzen

and jigger. She has four headsails with an aggregate of 646 square yards of

canvas in them. Her main and mizzen sails contain 2,424 square yards of canvas.

In her hull are 24,000 cubic feet of oak, 1,250,000 feet of yellow pine, 225

tons of iron, 98,000 treenails and 550 hackmatack knees.

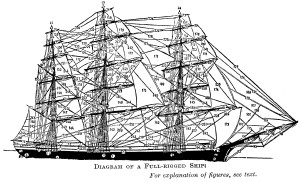

[CLICK IMAGE TO SEE LARGE RENDERING OF FULL-RIGGED SHIP]

[CLICK IMAGE TO SEE LARGE RENDERING OF FULL-RIGGED SHIP](e) PARTS OF A

FULL-RIGGED SHIP

1, hull; 2, bow; 3, stern; 4, cutwater; 5, stem; 6,

entrance; 7, waist; 8, run; 9, counter; 10, rudder; 11, davits; 12,

quarter-boat; 13, cat-head; 14, anchor; 15, cable; 16, bulwarks; 17, taffrail;

18, channels; 19, chain-plates; 20, cabin-trunk; 21, after-deck house; 22,

forward-deck house; 23, bowsprit; 24, jib-boom; 25, flying jib-boom; 26,

foremast; 27, mainmast; 28, mizzenmast; 29, foretopmast; 30, maintopmast; 31,

mizzen-topmast; 32, foretopgallantmast; 33, maintopgallantmast; 34,

mizzentopgallantmast; 35, foreroyalmast; 36, mainroyalmast; 37,

mizzenroyalmast; 38, foreskysailmast; 39, mainskysailmast; 40,

mizzenskysailmast; 41, foreskysail-pole; 42, mainskysail-pole; 43, mizzenskysail-pole;

44 fore-truck, 45, main-truck; 46, mizzen-truck; 47, foremast-head; 48,

mainmast-head; 49, mizzenmast-head; 50, foretopmast-head; 51, maintopmast-head;

52, mizzentopmast-head; 53, foretop; 54, maintop; 55, mizzentop; 56,

dolphin-striker; 57, outriggers; 58, foreyard; 59, mainyard; 60, cross

jack-yard; 61, fore lower topsail-yard; 62, main lower topsail-yard 63, mizzen

lower topsail-yard; 64, fore upper topsail-yard; 65, main upper topsail-yard;

66, mizzen upper topsail-yard; 67, foretopgallant-yard; 68, maintopgallant-yard;

69, mizzentopgallant-yard; 70, foreroyal-yard; 71, mainroyal-yard; 72,

mizzenroyal-yard; 73, foreskysail-yard; 74, mainskysail-yard; 75, mizzenskysail-yard;

76, spanker-boom; 77, spanker-gaff; 78, mainskysail-gaff; 79, monkey-gaff; 80,

lower studdingsail-yard; 81, foretopmast studdingsail-boom; 82, fore-topmast

studdingsail-yard; 83, maintopmast studding‑ sail-boom; 84, maintopmast

studdingsail-yard; 85, foretopgallant studdingsail-boom; 86, foretopgallant

studdingsail-yard; 87, maintopgallant studdingsailboom; 88, maintopgallant

studdingsail-yard; 89, fore-royal studdingsail-boom; 90, foreroyal studdingsailyard;

91, mainroyal studdingsail-boom; 92, mainroyal studding-sail-yard; 93,

bobstays; 94, bowsprit-shrouds; 95, martingale-guys; 96, martingale-stays; 97,

fore-chains; 98, main-chains; 99, mizzen-chains; 100, fore-shrouds; 101,

main-shrouds; 102, mizzen-shrouds; 103, foretopmast shrouds; 104,

maintopmast-shrouds; 105, mizzentopmast-shrouds; 106, foretopgallant-shrouds;

107, maintopgallant-shrouds; 108, mizzentopgallant-shrouds; 109,

futtock-shrouds; 110, futtock-shrouds; 111, futtock-shrouds; 112, forestay;

113, mainstay; 1I4, mizzenstay; 115; foretopmast-stay; 116, maintopmaststay;

117, spring-stay; 118, mizzentopmast-stay; 119, jib-stay; 120, flyingjib-stay;

121, foretopgallant-stay; I22, maintopgallant-stay; 123, mizzentopgallant-stay;

124, foreroyal-stay; 125, mainroyal-stay; 126, mizzenroyal-stay; 127,

foreskysail-stay; 128 mainskysail-stay; 129, mizzenskysail-stay; 130,

foretopmast-backstays; 131, maintopmast-backstays; 132,

mizzentopmast-backstays; 133, foretopgallant-backstays; 134,

maintopgallant-backstays; 135, mizzentopgallant-backstays; 136,

foreroyal-backstays; 137, mainroyal-backstays; 138, mizzenroyal-backstays; 139,

foreskysail-backstays; 140, mainskysail-backstays; 141,

mizzenskysail-backstays; 142, foresail or forecourse; 143, mainsail or

main-course; 144, crossjack; I45, fore lower topsail; 146 main lower topsail;

147, mizzen lower topsail; 148, fore upper topsail; 149, main upper topsail;

150, mizzen upper topsail; 151, foretopgallant-sail; 152, maintopgallant-sail;

153, mizzentopgallant-sail; 154, foreroyal; 155, mainroyal; 156, mizzenroyal;

157, foreskysail; 158, mainskysail; 159, mizzensky-sail; 160, spanker; 161,

mizzenstaysail; 162, foretopmast-staysail; 163, main. topmast lower staysail;

164, maintopmast upper staysail; 165, mizzentopmast-staysail; 166, jib; 167,

flying-jib; 168, jib-topsail; 169, maintopgallant-staysail; 170,

mizzentopgallant-staysail; 17I, mainroyal-staysail; 172, mizzenroyal-staysail;

173, lower studding-sail; 174, foretopmast-studding sail; 175,

maintopmast-studdingsail; 176, foretopgallant-studding sail; 177, maintopgallant-studding

sail; 178, foreroyal-studding sail; 179, mainroyal-studding sail; 180,

forelift; 181, mainlift; 182, crossjack-lift; 183, fore lower topsail-lift;

184, main lower topsail-lift; 185, mizzen lower topsail-lift; 186, spanker-boom

topping-lift; 187, monkey-gaff lift; 188, lower studdingsail-halyards; 189,

lower studdingsail inner halyards; 190, foretopmast studdingsail-halyards; 191,

maintopmast studdingsail-halyards; 192, foretop-gallant studdingsail-halyards;

193, maintopgallant studdingsail-halyards; 194, spanker peak-halyards; 195,

signal-halyards; 196, weather jib-sheet; 197, weather flying-jib sheet; 198,

weather jib topsail-sheet; 199, weather fore-sheet; 200, weather main-sheet;

201, weather crossjack-sheet; 202, spanker-sheet; 203, mizzentopgallant

staysail-sheet; 204, mainroyal staysail-sheet; 205, mizzenroyal

staysail-sheet; 206, lower studdingsail-sheet; 207, foretopmast

studdingsail-sheet; 208, foretopmast studdingsail-tack; 209, maintopmast

studdingsail-sheet; 210, maintopmast studdingsail-tack; 211, foretopgallant

studdingsail-sheet; 212, foretop-gallant studding sail tack; 213,

maintopgallant studdingsail-sheet; 214, maintopgallant studdingsail-tack; 215,

foreroyal studdingsail-sheet; 216, foreroyal studdingsailtack; 217, mainroyal

studdingsail-sheet; 218, mainroyal studdingsail-tack; 219, forebrace; 220,

mainbrace; 221, crossjack-brace; 222, fore lower topsail-brace; 223, main lower

topsail-brace; 224, mizzen lower topsail-brace; 225, fore upper topsail-brace;

226, main upper topsail brace; 227, mizzen upper topsail-brace; 228, foretopgallant-brace;

229, maintopgallant-brace; 230, mizzentopgallant-brace; 231, foreroyal brace;

232, mainroyalbrace; 233, mizzenroyal-brace; 234, foreskysail-brace; 235,

mainskysail-brace; 236, mizzenskysail-brace; 237, upper maintopsail-downhaul;

238, upper mizzentopsail-downhaul; 239, foretopmast maintopsail-downhaul; 240,

maintopmast studding sail-downhaul; 241, fore-topgallant studdingsail-downhaul;

242, maintopgallant studdingsail-downhaul; 243, clew-garnets; 244, clew-lines;

245, spanker-brails; 246, spanker-gaff vangs; 247, monkey-gaff vangs; 248, main

bowline; 249, bowline-bridle; 250, foot-ropes; 251, reef-points.

|