| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2017 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

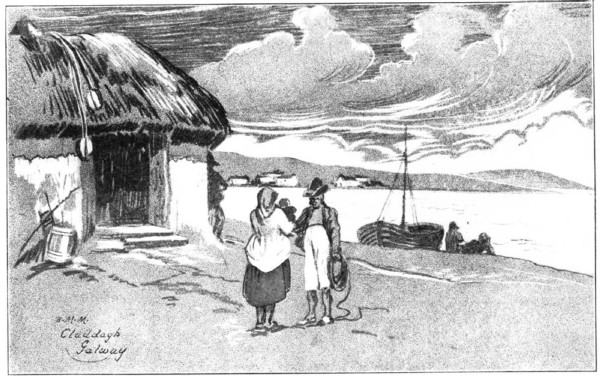

CHAPTER VI. GALWAY AND ITS BAY IT may not be recognized, it certainly is not a widely known fact, that Galway at one time — however extraordinary it may now appear — arrived at a pitch of mercantile greatness superior, with the single exception of London, to any port in what is now known as the British Isles. From an original letter from Henry Cromwell and the Irish Privy Council, dated Galway, 7th April, 1657, we learn that: “For situation, voisenage, and commerce it hath with Spain, the Strayts, West Indies, and other parts, noe towne or port in the three nations (London excepted) was more considerable.” “Another city so ancient as Galway does not exist in Ireland,” says an old-time traveller. “Its situation is flat and unpicturesque, but the universality of red petticoats, and the same brilliant colour in most other articles of female dress, gives a foreign aspect to the population, which prepares you somewhat for the completely Italian or Spanish look of most of the streets of the town.” “In Galway,” writes Köhl, “the metropolis of the west, and a Hesperian colony, he (the traveller) will find a quaint and peculiar city, with antiquities such as he will meet with nowhere else. The old town is throughout of Spanish architecture, with wide gateways, broad stairs, and all the fantastic ornaments calculated to carry the imagination back to Granada and Valencia. Then the town, with its monks, churches, and convents, has a completely Catholic air; and the population of the adjoining country have preserved something of their picturesque national costume.” From the earliest times, especially about the fourteenth century, and until a later period, extensive trade was carried on betwixt Spain and Ireland. Galway was always one of the principal ports frequented by foreigners. The richer merchants of the town made periodical visits to Spain, and returned with Spanish luxuries and Spanish ideas. The result of this was that mansions in Spanish style arose and were filled with Spanish furniture; while the ladies used in their dresses the bright colours and light textures of Spain. It is reasonable, too, to suppose that in many instances Spanish servants, seamen, and even workmen, formed alliances with the natives of the soil, and thus the population became, not only in dress but in blood, allied to their foreign visitors. Many of the houses built for the merchant princes of Galway still remain, though in a dilapidated state, and have come to be occupied by the poorest inhabitants. Truly, “Galway was a famous town when its Spanish merchants were princes; but their fine dwellings were at one time usurped and defaced by the rabble, and little remains of the interiors to show their ancient glory.” It is probable that, besides the Spaniards, the Italians also traded with Galway, and that banks were instituted by Jews from Lombardy. Little more than fifty years ago, “the tribes of Galway” claimed to themselves the exclusive right of exercising certain civil privileges. Just how far one may go in promulgating a theory, in a book such as this, remains an open question. With regard to the Spaniards in Ireland, it is not so much conjecture as to the time of their advent, or their numbers, as it is with the causes which led up to it. Galway was one day to be the pride and hope of Erin’s Isle. This we all know and recognize, and, with this end in view, huge warehouses and quays were built to accommodate a vast ocean-borne traffic which was to come and make it the rival of Liverpool. One may walk along these quays to-day and see the ruin of all this enterprise, for Galway, despite its seventeen thousand inhabitants, is a town which bears, in its every aspect, the appearance of a place that has already sunk into irretrievable decay. As a gateway to Connemara, Galway still exercises great influence on the prosperity of the west of Ireland, and, moreover, has an historic interest which cannot fail to be attractive to the tourist for all time to come. Recalling how James Lynch FitzStephen, in 1493, condemned and actually executed with his own hands his only son Walter, who had murdered a young Spaniard, brings us to the fact that Galway was at one time more a city of Spain than of Ireland. In ancient times Galway was the most famous port in Ireland, and had a very extensive trade, especially with the ports of Hispaniola. Many Spanish merchants, sailors, and fishermen settled here, until, at one time, probably one-fourth of the population of the town was pure Spanish. They built their houses after the Spanish pattern, and mingled with the native Irish population; but not, however, without leaving upon it the ineradicable mark and powerful impress of their own character, and imparting the superstition, the temperament, and the physical qualities of their race. Moreover, it is said that a large portion of the famed Armada was wrecked off the Galway coast; and that, in addition to those already there, these survivors settled and multiplied. In consequence, much of the ancient architecture — discernible even to-day — is obviously of Spanish origin; and there is no doubt that the Spaniards have left their impress on the features and character of the inhabitants of the town and the near-by districts. One notes this as he strolls through the market, where the women are selling fish, for the most part consisting of sea-bream, red mullet, conger-eels, and lobsters. In their complexions, their dark hair and eyes, their high cheek-bones, and their carriage, — in the mantilla-like way in which they wear their shawls, and in the brilliant colours of their costumes, — they bear a striking resemblance to the fisherwomen of Cadiz and Malaga. The men are even more strikingly Spanish. The speech is curious, too. It is Gaelic, but it is full of Spanish idioms and terminations. These people live for the most part in a village called the Claddagh, whose population formerly kept itself quite distinct from its Irish neighbours. The people married only among themselves; had their own religion; in a measure, their own municipal government; and pursued their own way without any reference to what went on around them. Of late, however, this exclusiveness has, to a large extent, been broken down. Still the Claddagh is a spot which has no parallel elsewhere in Ireland, and is a distinct survival of the original Spanish settlement.

CLADDAGH. The Galway fisheries are still, and always have been, an important economic factor in the life of these parts. Their conduct is a feature no less interesting in many ways than the more æsthetic aspects of the region. Nowhere else in the island can such a sight be seen as in the salmon season may be observed from Galway Bridge, when the water in the river is low. One looks over the bridge into the water, and sees what is apparently the dark bed of the river; but drop in a pebble, and instantly there is a splash and a flash of silver, and a general movement along the whole bed of the stream. Then one comes to know that what apparently were closely packed stones are salmon, squeezed together like herrings in a barrel, unable to get up-stream for want of water. This salmon fishery, together with the fisheries on the coast, constitute the staple industries of the district; and, as a business proposition, might appeal largely to some company promoter were he able to corner the supply and control the traffic. The hardihood of the population, their aptitude for seamanship, their industrious habits, and their thrifty instincts make them so capable of rising to any opportunities that may be offered to them, that there is no reason why Galway should not become as great a fishing-port as any on the east coast of England. Galway is full of memorials of its ancient days of commercial greatness, when wealthy merchant families inhabited the fine stone mansions now fallen into ruins; and tales of former glories are on everybody’s lips. There is no dearth of anecdote about Galway. Some of it is fact; much of it doubtless is not; but there seems no reason why one could not expand a short chapter of its history into a great book were he so inclined. Galway was practically “discovered” by the English in the thirteenth century, “when they took possession of the desirable little town,” and portioned it out among thirteen English families — those of Athy, Blake, Bodkin, Browne, Deane, D’Arcy, Lynch, Joyce, Kirwan, Martin, Morris, Skerret, and French. These became known as the Tribes of Galway, and before long became “more Irish than the Irish themselves.” This we learn from the written records; but, since they exist so completely and lucidly, there seems no reason to quarrel with the statement. The Lynches were, and are, the most numerous and important of the Tribes of Galway. The name is said to be aboriginal or at least Celtic, and again tradition has it that all the Lynches are descended from the daughter and heiress of a certain lord marshal of the county of Galway in the year 1280. In 1442 a certain Edmond Lynch FitzThomas built at his own expense a bridge called the West Bridge, and twenty years later another, Gorman Lynch, held a patent for coining money; and yet another, James Lynch FitzStephen, the famous Warden of Galway, whose notoriety has been described in Dutton’s “Survey of Galway” (1824), lived at the end of the same century. As described by Dutton, the “notorious” incident arose from Lynch FitzStephen having sent his only son to Spain on some commercial affairs, who, returning with the son of his father’s Spanish friend and a valuable cargo, conspired with the crew to murder and throw him overboard, and convert the property to their own use. One of the party, as providentially happens in most such cases, revealed the horrid transaction to the mayor. He tried and condemned his son to death, and appointed a day for his execution. It was imagined by his relatives that, through their intercession, and the consideration of his being an only son, he would not proceed to put the sentence into execution. He told them to come to him on a certain day, and they should have his determination. Early on the day appointed, they found the son hanging out of one of the windows of his father’s house. It was commemorated by the cross-bones in Lombard Street. Further records have it that the stone bearing the cross-bones was not put up for many years after the transaction, when it was erected on the wall of St. Nicholas’s churchyard, and bore the inscription: 1524Remember Death. All is vanity of vanities.  Judge Lynch’s House, Galway From this incident — a recorded fact of history be it remembered — the familiar “Americanism” (sic) of “lynch-law” probably received its derivation. At any rate, the circumstance is one of significance and plausibility, or it shows once again how the seed of coincidence takes root and thrives many thousands of miles from the land of its first growth. Galway has ever been an important commercial centre, and rightly enough points out the fact that to be as proud and honest as a Galway merchant is to be reckoned as one of the upright of this world. It is a curious fact that, notwithstanding the maritime resources of Galway, salt was one of the commodities imported to it from Spain, and so highly was the import prized that John French, who was mayor in 1538, bore the distinguishing appellation of Shane ne Sallin. The county of Galway must have been a quarrelsome and belligerent community in times past, judging from the fact that local history gives elaborate accounts of certain fighting gentlemen known as “Blue-Blaze-Devil-Bob,” “Nineteen-Duel-Dick,” “Hair-Trigger-Pat,” and “Feather-Spring-Ned.” But these honourable cognomens are no longer cited with a voice of triumph by the leading citizens; and it may be presumed that Hair-Trigger and Blaze-Devil exploits are becoming rarer. There is no reason to doubt but that this is so, judging from appearances and experiences with which one comes in contact to-day. Historians, anthropologists, and antiquarians have attempted before now to draw comparisons between the inhabitants of Galway and those of Spain. The circumstance has been authenticated and remarked frequently; but it is interesting, if not valuable, to have a native first-hand opinion on the subject. An elderly gentleman whom the author once met, who had lived in Spain and Galway respectively a number of years, remarked many characteristics in common among the middle class; and, again, at the proceedings of a philosophical society, it was stated that “in the lower and more vulgar classes, the old Milesian habits still prevail.” Rather a contemptuous way of putting it this, but indolence, or at least something more than a trace of it, is, one must admit, still apparent in both places. Of the spoken speech of Galway much has been written, and with good excuse, for Spanish idioms and words still come to the surface here, as does the French tongue in certain parts of Scotland. The writer recalls an incident in the experiences of an ardent automobilist, which took place in the neighbourhood of Galway: He was driving down an extremely steep hill, and was barely able to keep the automobile in hand. There was a safe “run-down” ahead, but a number of Irish-speaking children kept dancing and running around in front, deaf to his uncomprehended cries of “Get away! Take care! you’ll be run over!” and it seemed likely that some one would be killed when the motor-car should get its head. Just as that disaster became imminent, however, the driver remembered the one Irish word he understood, — “Faugh-a-ballagh!” (a famous war-cry of olden times, equivalent to “Clear the way”). He only remembered it as the name of a race-horse, but yelled it out; and the children sprang out of his way like arrows, just in time to let the car rush safely past. Galway, too, has the reputation of being one of the few counties left (Cork is another) where the typical “Paddy” of romance is to be found. That is, so far as his or her dress is concerned; and, truth to tell, it has all but disappeared from here, for it is only of a bright summer Sunday, or some local feast-day, that the Irishman, dressed as in the chorus of a comic opera, is ever seen. In Galway itself, on an important market-day, he is still to be seen, and forms a picturesque note to the surroundings which the sentimentalist would indeed otherwise miss. He is found in knee-breeches and tail coat, high caubeen with a pipe stuck in it, and long home-knit stockings, accompanied by the Galway women in short scarlet petticoat and close-hooded cloak. All the latter wear this dress, by the way. There is practically not a woman of the working class in the town — certainly not one in the Claddagh fishing quarter — who does not cling to this bit of colour, as thick as a blanket and very fleecy. It is spun, woven, and made at home; and, as a result, raggedness is exceedingly infrequent among the Galway natives. Indeed, all Connemara is remarkable for the clean, neat, and whole clothing of its people, who are otherwise poverty-stricken. It is only in great towns, where the poor clothe themselves in slop-shop stuffs and cast-off garments of the upper classes, that they are ragged and unkempt. Homespuns and tweeds, such as we are accustomed to see only in smart coat and skirt costumes, or expensive shooting suits, are the daily wear of every one. They cost little, — only the keep of a few hardy mountain sheep, from which the wool is obtained, the loan of a spinning-wheel from a neighbour, and the small fee of a local hand-loom weaver. Thus the people of Mayo and Galway, though often at other times miserably clad, go about with a neat “tailor-made” aspect that is astonishing. The tourists, i. e., the ladies, buy the charming Claddagh cloaks and bolts of homespun, which ultimately appear in more fashionable centres as the last thing in the world of fashion. Another form of souvenir, which appears to be irresistible, is the peculiar marriage-ring of Claddagh. This particular pattern has been the marriage-ring of the Claddagh fishing tribes for many centuries. Indeed, every peasant matron in the county wears one. The design is that of a heart over two clasped hands, surmounted by a crown, the signification being “Love and friendship reign.” Among the upper classes in Ireland, these rings are often used as guards for engagement and wedding rings. A more interesting monument than any memorial stone in the abbey, or, indeed, in Sligo, is Misgoun Meave, which dominates the whole neighbourhood, the traditional burial-place of Queen Meave. On the top of Knocknarea, a hill over one thousand feet high, stands an immense cairn of stones, almost like a second peak to the hill. Here, overlooking a wide range of beautiful seacoast and country, tradition states that the famous Irish Queen of Connaught, after she had buried three husbands, chose her tomb. Nearly two thousand years have passed since the date popularly assigned to her reign, but there can be no reasonable doubt that she was a thoroughly genuine personality, and left her individual mark upon the history of her time. Like Boadicea, she led her own armies in person, and seems, according to the wild legends told of her exploits, to have been an Amazon of terrible reputation and dauntless courage. She had the red-gold hair that may still be seen in Connaught, — a heritage popularly supposed to have descended from her, — and wore it flowing like a mantle over her. Her beauty was considerable, her temper ungovernable, and her virtue, apparently, doubtful. She was often accompanied to battle by her stalwart sons of middle age; and her own years are reported to have counted well over a century before death at last loosened her iron grip on blood-stained Connaught. One can well understand how such a woman, dying, chose to be buried where, even in death, her sightless eyes might look down upon the land of lake and island, forest, hill, and sea that had been hers so long. A lively French writer, who travelled in Ireland in the early part of the nineteenth century, was evidently much smitten with the fair sex.

He says, in part:

“The greatest gaiety

reigns there, — in fact, the belles of Galway are capable of

instructing most French young ladies in the art of coquetry. In the

early morning, one sees five or six young ladies, perched upon a

jaunting-car, go two miles from the city to refresh their charms by a

sea bath, and in the afternoon, if there be no assembly, they go from

shop to shop, buying, laughing, and chatting with their friends.

There are many in this city who grow old without knowing it.”| All of which seems a simple and innocuous enough amusement. In spite of which, however, no very apparent coquettishness on the part of Galway young ladies is to be noted to-day, — at least, it has not been observed by the writer of this book. Perhaps that merely points to a lack of susceptibility on his part. T. P. O’Connor once told the story of a travelling showman who brought to Galway from America a panorama of America. “He knew what he was about,” said Mr. O’Connor, “when he declared that Chesapeake Bay was the finest bay in the world with two exceptions, — the Bay of Naples and the Bay of Galway; and he was very loudly cheered. “Without exaggeration, it is a beautiful bay, almost landlocked, with mountains — small enough in comparison with others, but to the untravelled eye of the Irish villager solemn and imposing as the Matterhorn — bounding it on the far side, and with a somewhat narrow mouth opening out into the Atlantic. A mouth that, under the light of morning or evening, is something to suggest either the vastness of this world of human beings, or the anticipation of the greater vastness of that other world beyond, which haunted the imaginations and thoughts of the pious Catholics of that region.” These few lines serve to give a most truthful word-picture of Galway Bay; and also a glimpse of the brilliancy with which Mr. O’Connor writes. Continuing, Mr. O’Connor writes of his school-days in Ireland thus, in words which give a far more sympathetic and clear knowledge of things as they are — or were — than most reminiscences of a like nature: “There had come to my native town of Athlone a new school, and it was but natural that my father should like me to go there, and, accordingly, I had no more of Galway — except at vacation-time — for five long years. “These years belong to my native town and the school near it; and they were among the most unhappy years of my life. “I remember still the bitter flood of tears I wept the first day after I returned to Athlone from the year or so I had spent in Galway. “But Galway had to me, then, many of the chief charms of boyhood. There was a second house behind that in which we lived, which was usually unoccupied. From its roof you could see one of those beautiful scenes that, once seen, haunt one ever afterward. Beyond the town you could catch sight of the sea; and there, on certain evenings, you saw the fleet of herring-boats as they went out for their night-watch and night harvest of fish, — a sight that was more like something of fairy-land than of reality, though I dare say the poor crews found much grimmer reality than romance in their hard and laborious night-watches.” Just off the mouth of Galway Bay are the Aran Islands. Between them and the mainland the sea is often so rough as to make it impossible for small boats to undertake the crossing. The principal food of the inhabitants is dried fish, naturally a home product. The chief patron saint of Munster, aside from St. Finbarr’s association with Cork, was St. Albeus. He had already been converted by certain Christianized Britons, and had travelled to Rome before the arrival of St. Patrick among the Irish. After his return, he became the disciple and fellow labourer of that great apostle, and was ordained by him as first Archbishop of Munster, with his see fixed at Emely, long since removed to Cashel. He possessed, according to the chroniclers, the wonderful art of making men, not only Christians, but saints, and for this great ability King Engus bestowed upon him the isles of Aran in Connaught, where he founded a great monastery. So famous did the island become for the sanctity of its people that it was long called “Aran of Saints.” The rule which St. Albeus drew up for them is still extant in the old Irish manuscripts. Though zeal for the divine honour and charity for the souls of others fixed him in the world, he was always careful, by habitual recollection and frequent retreats, to nourish in his own soul the pure love of heavenly things, and to live always in a very familiar and intimate acquaintance with himself and in the daily habitual practice of the most perfect virtues. In his old age, it was his earnest desire to commit to others the care of his dear flock, that he might be allowed to prepare himself in the exercise of holy solitude for his great change. For this purpose, he begged that he might be suffered to retire to Thule, the remotest country toward the northern pole that was known to the ancients, which seems to have been Shetland, or, according to some, Iceland or some part of Greenland; but the king guarded the ports to prevent his flight, and the saint died amidst the labours of his charge in 525, according to the Ulster and Innisfallen annals. These islands are three in number: Inishmore, Imishmaan, and Inisheer, and contain among them such a wealth of pagan and Christian antiquities as is excelled by no locality in Ireland of the same area: perhaps fifteen square miles in all.

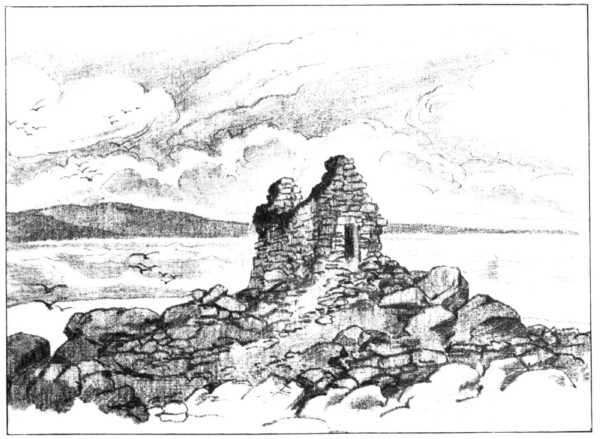

THE CHURCH OF THE CANONS, ARAN. There is a work published in Dublin, known as “The Illustrated Programme of the Society of Architects,” which contains a brief account of the wealth of the architectural and historical lore of these parts. More one could not wish to know unless he were profoundly interested, and less would not even satisfy him if he became at all enamoured of these islands, so full of dreary old places and quaint customs, to say nothing of the wealth of tradition and legend which hangs about it all. Westward, the nearest land is America, where so many stalwart sons of Galway — and daughters, too — have migrated. Here the peasants still reverently believe in the far-famed land of Hy or O, — Brazil, the paradise of the ancient pagan Irish. The praises of the “great fictitious island” were sung by the bards of olden time, and tradition has perpetuated its fame as a “land of perpetual sunshine, abounding in rivers, forests, mountains, and lakes. Castles and palaces arise on every side, and, as far as the eye can reach, it is covered with groves, bowers, and silent glades; its fields are ever green, with sleek cattle grazing upon them; its groves filled with myriads of birds. It is only seen occasionally, owing to the long enchantment, which will, they say, now soon be dissolved. The inhabitants seem always young, taking no heed of time, and lead lives of perfect happiness. In many respects this fabulous land resembles the Tirna-n’oge, the pagan Irish Elysium.” Among the chief — and assuredly unique — reliques of these few square miles of terra firma are the ruins of the old fortified Castle of Ardkyne, in which are built the remains of the great church of St. Enna, chief of the Oriels, who, upon his conversion, abandoned his secular rule, and eventually settled (not later than A. D. 489) in Aran, which henceforth became Ara-na-noamh, “Aran of the Saints.” The church was one of several destroyed by the soldiers of Cromwell; but its plan, about twenty by ten feet, can be traced behind the village. Above the village is the stump of a round tower, and, on the ridge, the oratory of St. Benen, a unique specimen of early Irish church architecture, which has remarkably steep pitched gables. The window in the east wall has its head and splay of a single stone. The narrow north doorway has inclined jambs. If the name refers to the apostle of Connaught, St. Benen of Armagh, it must be a dedication, as he died in 468. The building may with confidence be assigned to the sixth century. St. Edna’s burial-place, known as Tegloch Edna, is another curious premediæval church. On the Aran Islands there are no bogs, but one has, instead, to dodge his footsteps in and out among pebbles and rolling stones of every size and shape. This is particularly so if one is to make the journey to Dun Ængus, one of the finest prehistoric forts of Western Europe; called, indeed, by Dr. Hindes Petrie, “The most magnificent barbaric monument now extant in Europe.” It is, undoubtedly, the most noteworthy object in Aran. It consisted originally of a triple line of works, but the two inner lines, of horseshoe shape on the verge of a bold headland, are those best preserved. Tradition assigns it to Ængus, a Firbolg chief who lived about two thousand years ago. The chevaux-de-frise defending the second line is unmistakable, and the whole is as majestic in its grandeur as its supposed antiquity might indicate. Temple MacDuagh, near Kilmurvy, is a “cyclopean” church of the seventh century, and Dun Oghil is a grand fort consisting of a circular cashel, within a second, which is roughly square. These are the chief features of the great island, with the Temple Brecan, which has a chancel of rude ancient masonry, a choir which more nearly approaches our own time by four or five hundred years and is still modern, and a sacred enclosure devoted to the burial of saints, of which the Irish calendar seems quite full. On Inisheer are the remains of an ancient place of worship dedicated to St. Cavan, brother to St. Kevin, the legend of whose life everywhere confronts one in County Wicklow. There is another to St. Gobnet, abbess of the sixth century. |