|

Web and Book design, |

Click Here to return to |

|

Web and Book design, |

Click Here to return to |

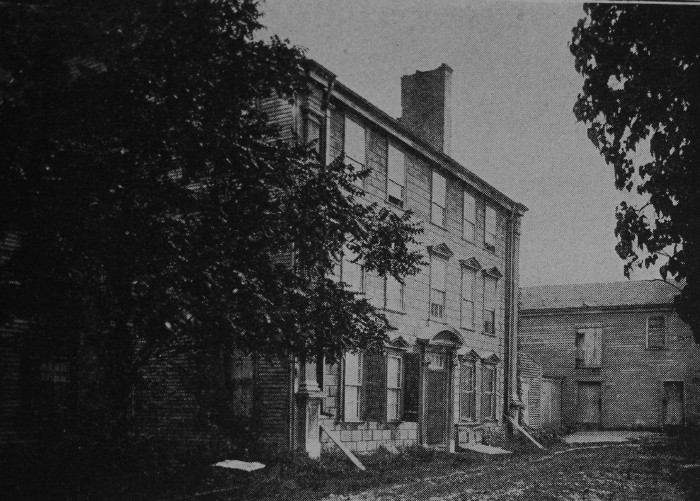

ONE of the most picturesque houses in all Middlesex County is the

Royall house at Medford, a place to which Sir Harry Frankland and his lady used

often to resort. Few of the great names in colonial history are lacking,

indeed, in the list of guests who were here entertained in the brave days of

old.

The house stands on

the left-hand side of the old Boston Road as you approach Medford, and to-day

attracts the admiration of electric car travellers just as a century and a half

ago it was the focus for all stage passenger's eyes. Externally the building

presents three stories, the upper tier of windows being, as is usual in houses

of even a much later date, smaller than those underneath. The house is of brick,

but is on three. sides entirely sheathed in wood, while the south end stands

exposed. Like several of the houses we are noting, it seems to turn its back on

the high road. I am, however, inclined to a belief that the Royall house set the

fashion in this matter, for Isaac, the Indian nabob, was just the man to assume

an attitude of fine indifference to the world outside his gates. When in 1837,

he came, a successful Antigua merchant, to establish his seat here in old

Charlestown, and to rule on his large estate, sole monarch of twenty-seven

slaves, he probably, felt quite indifferent, if not superior, to strangers and

casual passers-by.

His petition of

December, 1737, in regard to the "chattels" in his train, addressed to the

General Court, reads:

"Petition of Isaac

Royall, late of Antigua, now of Charlestown, in the county of Middlesex, that

he removed from Antigua and brought with him among other things and chattels a

parcel of negroes, designed for his own use, and not any of them for

merchandise. He prays that he may not be taxed with impost."

The brick quarters which the slaves occupied are situated on the

south side of the mansion, and front upon the courtyard, one side of which they

enclose. These may be seen on the extreme right of the picture, and will remind

the reader who is familiar with Washington's home at Mount Vernon of the quaint

little stone buildings in which the Father of his Country was want to house his

slaves. The slave buildings in Medford have remained practically unchanged, and

according to good authority are the last visible relics of slavery in New

England.

The Royall estate offered a fine example of the old-fashioned garden. Fruit trees and shrubbery, pungent box bordering trim gravel paths, and a wealth of sweet-scented roses and geraniums were here to be found. Even to-day the trees, the ruins of the flower-beds, and the relics of magnificent vines, are imposing as one walks from the street gate seventy paces back to the house-door.

The carriage visitor

and in the old days all the Royall guests came under this head either

alighted by

the front entrance or passed by the broad drive under the shade of the fine old

elms around into the courtyard paved with small white pebbles. The driveway has

now become a side street, and what was once an enclosed garden of half an acre

or more, with walks, fruit, and a summer-house at the farther extremity, is now

the site of modern dwellings.

This summer-house,

long the favourite resort of the family and their guests, was a veritable

curiosity in its way. Placed upon an artificial mound with two terraces, and

reached by broad flights of red sandstone steps, it was architecturally a model

of its kind. Hither, to pay their court to the daughters of the. house, used to

come George Erving and the young Sir William Pepperell, and if the dilapidated

walls (now taken dawn, but still carefully preserved) could speak, they might

tell of many an historic love tryst. The little house is octagonal in form, and

on its bell-shaped roof, surmounted by a cupola, there poises what was

originally a figure of Mercury. At present, however, the statue, bereft of both

wings and arms, cannot be said greatly to resemble the dashing god.

The exterior of the

summer-house is highly ornamented with Ionic pilasters, and taken as a whole is

quaintly ruinous. It is interesting to discover that it was utility that led to

the elevation of the mound, within which was an ice-house! And to get at the ice

the slaves went through a trap-door in the floor of this Greek structure!

Isaac Royall, the

builder of the fine old mansion, did not long live to enjoy his noble estate,

but he was succeeded by a second Isaac, who, though a "colonel," was altogether

inclined to take more care for his patrimony than for his king. When the

Revolution began, Colonel Royall fell upon evil times. Appointed a councillor by

mandamus, he declined serving "from timidity," as Gage says to Lord Dartmouth.

Royall's own account of his movements after the beginning of "these troubles,"

is such as to confirm the governor's opinion.

He had prepared, it

seems, to take passage for the west Indies, intending to embark from Salem for

Antigua, but having gone into Boston the Sunday previous to the battle of

Lexington, and remained there until that affair occurred, be was by the course

of events shut up in the town. He sailed for Halifax very soon, still intending,

as he says, to go to Antigua, but on the arrival of his son-in-law, George

Erving, and his daughter, with the troops from Boston, he was by them persuaded

to sail for England, whither his other son-in-law, Sir William Pepperell

(grandson of the hero of Louisburg), had preceded him. It is with this young Sir

William Pepperell that our story particularly deals.

The first Sir

William had been what is called a "self-made man," and had raised himself from

the ranks of the soldiery through native genius backed by strength of will. His

father is first noticed in the annals of the Isles of Shoals. The mansion now

seen in Kittery Point was built, indeed, partly by this oldest Pepperell known

to us, and partly by his more eminent son. The building was once much more

extensive than it now appears, having been some years ago shortened at either

end. Until the death of the elder Pepperell, in 1734, the house was occupied by

his own and his son's families. The lawn in front reached to the sea, and an

avenue a quarter of a mile in length, bordered by fine old trees, led to the

neighbouring house of Colonel Sparhawk, east of the village church. The first

Sir William, by his will, made the son of his daughter Elizabeth and of Colonel

Sparhawk, his residuary legatee, requiring him at the same time to relinquish

the name of Sparhawk for that of Pepperell. Thus it was that the baronetcy,

extinct with the death of the hero of Louisburg, was revived by the king, in

1774, for the benefit of this grandson.

ROYALL HOUSE, MEDFORD, MASS.

PEPPERELL HOUSE, KITTERY, MAINE

In the Essex Institute at Salem, is preserved a two-thirds length

picture of the first Sir William Pepperell, painted in 1751 by Smibert, when the

baronet was in London. Of this picture, Hawthorne once wrote the humorous

description which follows: "Sir William Pepperell, in coat, waistcoat and

breeches, all of scarlet broadcloth, is in the cabinet of the Society; he holds

a general's truncheon in his right hand, and points his left toward the army of

New Englanders before the walls of Louisburg. A bomb is represented as falling

through the air it has certainly been a long time in its descent."

The young William

Pepperell was graduated from Cambridge in 1766, and the next year married the

beautiful Elizabeth Royall. In 1774 he was chosen a member of the governor's

council. But when this council was reorganised under the act of Parliament, he

fell into disgrace because of his loyalty to the king. On November 16, 1774, the

people of his own county (York), passed at Wells a resolution in which he was

declared to have " forfeited the confidence and friendship of all true friends

of American liberty, and ought to be detested by all good men."

Thus denounced, the

baronet retired to Boston, and sailed, shortly before his father-in-law's

departure, for England. His beautiful lady, one is saddened to learn, died of

smallpox ere the vessel had been many days out, and was buried at Halifax. In

England, Sir William was allowed £500 per annum by the British government, and

was treated with much deference. He was the good friend of all refugees from

America, and entertained hospitably at his pleasant home. His private life was

irreproachable, and he died in Portman Square, London, in December, 1816, at

the age of seventy. His vast possessions and landed estate in Maine were

confiscated, except for the widow's dower enjoyed by Lady Mary, relict of the

hero of Louisburg, and her daughter, Mrs. Sparhawk.

Colonel Royall,

though he acted not unlike his son-in-law, Sir William, has, because of his

vacillation, far less of our respect than the younger man in the matter of his

refusal to cast in his lot with that of the Revolution. In 1778 he was publicly

proscribed and formally banished from Massachusetts. He thereupon took up his

abode in Kensington, Middlesex, and from this place, in 1189, he begged

earnestly to be allowed to return " home " to Medford, declaring he was "ever a

good friend of the Province," and

expressing the wish to marry again in his own country, "where, having already

had one good wife, he was in hopes to get another, and in some degree repair his

loss." His prayer was, however, refused, and he died of smallpox in England,

October, 1781. By his will, Harvard

College was given a tract of

land in

Worcester County, for the foundation of a professorship, which still bears his

name.

It is not, however,

to be supposed that in war time so

fine a place as the Royall mansion

should have been left unoccupied.

When the yeomen

began pouring into the environs of Boston, encircling it with a belt of steel,

the New Hampshire levies pitched their tents in Medford. They found the Royall

mansion in the occupancy of Madam Royall and her accomplished daughters, who

willingly received Colonel John Stark into the house as a safeguard against

insult, or any invasion of the estate the soldiers might attempt. A few rooms

were accordingly set apart for the use of the bluff old ranger, and he, on his

part, treated the family of the deserter with considerable respect and

courtesy. It is odd to think that while the stately Royalls were living in one

part of this house, General Stark and his plucky wife, Molly, occupied quarters

under the same roof.

The second American

general to be attracted by the luxury of the Royall mansion was that General

Lee whose history furnishes material for a separate chapter. General Lee it was

to whom the house's echoing corridors suggested the name, Hobgoblin Hall. So

far as known, however, no inhabitant of the Royall house has ever been disturbed

by strange. visions or frightful dreams. After Lee, by order of Washington,

removed to a house situated nearer his command, General Sullivan, attracted, no

doubt, by the superior comfort of the old country-seat, laid himself open to

similar correction by his chief. In these two cases it will be seen Washington

enforced his own maxim that a general should sleep among his troops.

In 1810, the Royall

mansion came into the possession of Jacob Tidd, in whose family it remained half

a century, until it had almost lost its identity with the timid old colonel and

his kin. As "Mrs. Tidd's house" it was long known in Medford. The place was

subsequently owned by George L. Barr, and by George C. Nichols, from whose hands

it passed to that of Mr. Geer, the present owner. To be sure, it has sadly

fallen from its high estate, but it still remains one of the most interesting

and romantic houses in all New England, and when, as happens once or twice a

year, the charming ladies of the local patriotic society powder their hair, don

their great-grandmother's wedding gowns and entertain in the fine old rooms, it

requires only a slight gift of fancy to see Sir William Pepperell's lovely bride

one among the gay throng of fair women.