|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Click here to go

to |

|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Click here to go

to |

VIII

PICTURESQUE SPOTS

We have thus far gone, Antiquary now remarked, the rounds of what comprised the little, early Town of Boston. As we have found, it really does not extend from one extreme to the other more than a morning’s walk, and few, very few, actual memorials are still to be seen. There yet remain picturesque spots here and there, which make it possible to recall some of the agreeable features of a somewhat later age.

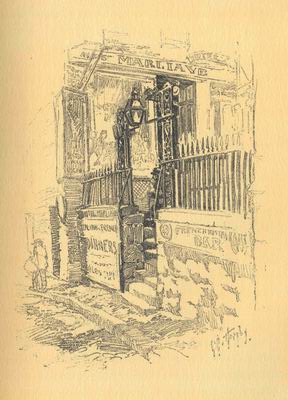

In byways off the thoroughfares through which we have just been passing are one or two of these spots that escape the officially guided tourist’s eye. Such is the quaint iron gateway at the foot of the short court — Bosworth Street it is now — opening from Tremont Street opposite the old Granary Burying-ground. We find the court ending at a low stone barricade, with flights of heavy, rough, well-worn stone steps in the middle, leading down to the gateway; and the gateway opening upon a narrow cross street of a single team’s width, — Province Street of to-day, running between School and Bromfield streets, the Governor’s Alley of Province days. For this, with Province Court opening from it eastward, was originally the avenue to the stables and rear grounds of the Province House. The gateway is not an ancient affair; it is of early nineteenth-century date, set up, perhaps, when the court was opened, in the eighteen twenties, as Montgomery Place, a court of genteel dwellings.

The Iron Gate between Province and Bosworth Streets

This court has an added interest as the dwelling-place of Doctor Holmes for eighteen years, — from 1841, the year after his marriage, till his removal to Number 164 Charles Street, — where he wrote the Autocrat papers in large part, and those earlier poems which established him in the affections of Boston as its best beloved local bard; and where all his children were born. His was “that house at the left hand next the further corner” yet standing, which he describes in the Autocrat as the Professor’s house. “When he entered that door, two shadows glided over the threshold; five lingered in the doorway when he passed through it for the last time, — and one of the shadows was claimed by its owner to be longer than his own.” This lengthening shadow was that of “My Captain” of the Civil War, and Mr. Justice Holmes of the United States Supreme Court to-day.

A spot of earlier date and of different interest is found a little way up town, on Washington Street, opposite Boylston Street and near the corner of Essex. If we look sharp, we shall see on a tablet affixed to the face of a building here a rude picture of a tree. This marks the site of the “Liberty Tree”, a broad-spreading elm, beneath which was “Liberty Hall”, the popular gathering place of the “Sons of Liberty” in the Revolutionary days. Naturally, at the Siege the British soldiers chopped it down.

Our final ramble is over the Old West End: the first West End, lying north and west of the slopes of Beacon Hill between the foot of Scollay Square at Sudbury Street and the River Charles. Originally its north bound was the North Cove, or Mill Pond, the water reaching Leverett Street at one point and cutting up toward the foot of Temple Street at Cambridge Street, while high-water mark crossed Cambridge Street at its junction with Anderson Street coming down the hill. This was the cove, we recalled, that the earth from the cutting of Beacon Hill top in 1811—1823 went to fill. It is an untidy quarter now, this Old West End, and in parts sordid. The pleasant old streets, and Bowdoin Square, its once fair central feature, with their refined homes of respectability and imposing mansion-houses set in fine gardens, are now sadly blemished with ill-favored structures replacing the handsome dwellings, while pretty much all of the quarter is deplorably shabby. Yet here and there we come upon picturesque spots and a landmark or two of value.

Most refreshing was the sight of the old West Meeting-house setting back from and above Cambridge Street, now preserved and protected by its use as the West End Branch of the Boston Public Library. In this we have an admirable example of a favored type of brick meeting-house at the opening of the nineteenth century. It dates from 1806, as one of the tablets on its face records, and replaces the first West Church, a house of wood, erected in 1737. The first West Church was the meeting-house which was used as a barrack during the Siege, and the steeple of which was taken down because it had been used by the “rebels” for signaling the American Camp at Cambridge, just before the Siege. It was demolished to make way for the present structure which occupies its site. In its history of nearly one hundred and seventy years as a place of worship, the West Church was the pulpit of but five pastors in succession; and the services of two of the five covered the whole period of the present meeting-house. These were Charles Lowell, father of James Russell Lowell, who served from 1806 till his death in 1861, fifty-five years, and Cyrus A. Bartol, first from 1837 to 1861 as Doctor Lowell’s colleague, and afterward as sole pastor till his death in 1901, a service in all of sixty-five years. The second of the five, the Reverend Jonathan Mayhew, 1747—1766, has been claimed not only as a fearless early Revolutionary patriot, but also as the first preacher of Unitarianism in Boston pulpits, and, too, by the Universalists as the first Boston preacher of their faith. It was gratifying to find the old entrance square, or park, well cared for; and the oaks that Doctor Lowell had transplanted here from the grounds of his Cambridge “Elmwood” where they had been raised from acorns, our guest was told. And the colonial brick and iron fence enclosing the square, with the handsome gate and the old-fashioned swinging sign above it, added the pleasing finishing touches to this attractive spot in a depressingly unattractive neighborhood.

Lynde Street, at the side of the church and running over a knoll to Green Street, is one of the older streets of the quarter and was new and of the highest respectability when the first West Church was built, which faced it. The street was cut through “Lynde’s Pasture” and was named for the Lynde family, which, beginning with Simon Lynde, a colonial Boston merchant and large owner of Boston realty, rose to larger distinction through Simon’s son and grandson, Benjamin and Benjamin, 2d, both of whom became chief justices of the Province. The latter presided at the trial of Captain Preston, after the “Boston Massacre” of 1770, when Preston was defended by the patriot leaders, John Adams and Josiah Quincy. Leverett Street, practically a continuation of Lynde Street across Green Street, is of about the same age and was of similar high character in its prime, albeit after the opening of eighteen hundred the almshouse and the jail were established here. It was named for Governor Leverett, who was a large landowner in these parts. To-day we find it eminently a foreign quarter, with Russian Jews largely herded here, the cheerful old houses transformed into or supplanted by dismal tenements and bedaubed shops. Yet in this unkempt thoroughfare the Artist pointed out more than one picturesque spot and made a sketch of a bit of the street. Once there were quiet little residential courts off the street, and there yet remain a foot passage or two between thoroughfares.

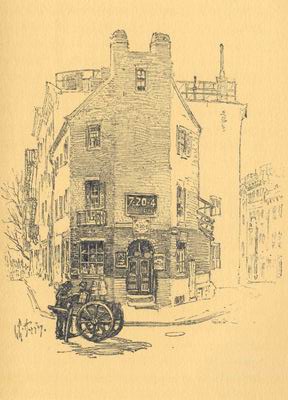

The Quaint Corner where Poplar and Chambers Streets meet

Through one of these — Hammond Avenue it is now loftily designated, though not wide enough for three to walk abreast — we press to the thoroughfare of Chambers Street, parallel with Leverett. Here again we are in a once choice neighborhood fallen upon sorry days, yet retaining picturesqueness in parts, and remnants of past glory. These remnants are mostly to be seen in the old streets running southward from Chambers, —Poplar, Allen, McLean. Of one quaint corner, where Chambers and Poplar streets meet, the Artist makes a sketch for us. Another picturesque corner we note is where Chambers and McLean meet, opposite the church — an old-time Unitarian meeting-house turned Roman Catholic. Taking McLean Street, we have a pleasing approach to the great domain of the old Massachusetts General Hospital with a part of the main building of Bulfinch’s design appearing before us at the end of the vista. This hospital, the Englishman was aware, is especially distinguished as the institution in which the first extensive surgical operation on a patient under the influence of ether was successfully performed. That was in October, 1856, and our guest might see hanging in the main building a picture commemorating the event, with portraits of the surgeons and physicians present on the great occasion; while in the Public Garden is J. Q. A. Ward’s commemorative monument. Founded in 1799, incorporated in 1811, and opened to patients in 1821, we remarked that this hospital was the second to be established in the country, the Pennsylvania Hospital having been the first. While numerous other great modern hospitals, some more splendidly endowed, have since been erected in Boston, we were confident that we were but echoing the best opinion when we assured our guest that it continues one of the most complete and perfectly organized institutions of its class. It is a little city, now, of fine buildings finely equipped, yet the Bulfinch granite structure, the central part of the first main building, remains the most picturesque.

At this spot, dedicated to the alleviation of human suffering, the Artist and Antiquary found a suitable occasion for telling their intelligent guest, the Englishman, that the complete separation between the Past and Present was well expressed in the surrounding neighborhood. Where once stood the comfortable houses of prosperous Boston, now on every hand are the homes, humble indeed but still homes, of many races, secure in the liberties that his kin beyond the seas had nobly won.

As we parted, the Englishman, not without emotion, admitted that he had seen and heard many things to confirm a belief with which he had begun our little tours, that the greatness of his race was still as well carried forward in this early home of sedition and rebellion as in the Mother Isle itself.