|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

II

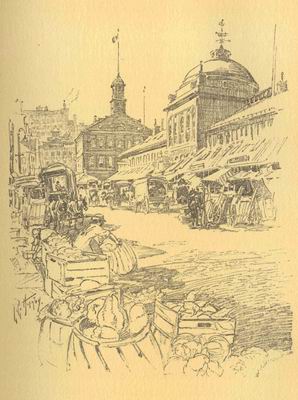

OLD STATE HOUSE, DOCK SQUARE, FANEUIL HALL

The first governor’s “mansion”, the first minister’s house, the meeting-house which was the first public structure to be erected, set up in the Town’s second summer, and the dwellings and warehouses of the first shopkeeper and of the wider merchant-traders, were grouped about the Market Place on the central “Great Street to the Sea.” Other first citizens located in the neighborhood of the Town Dock. Others along the High Waye between the Dock and School and Bromfield streets; on Milk Street; and round about the “Springgate” — Spring Lane — where was one of those bounteous springs which had drawn Winthrop and his followers to the peninsula. A few were scattered on School Street; on the nucleus of Tremont Street along the spurs of Beacon Hill; and about Hanover Street and the other lane to the North End. The first tavern was set up on the High Waye, in comfortable reach of the center of things. The occupation of the North End was begun actively within the Town’s first decade.

The pioneer houses were generally of one story and with thatched roof. But very soon more substantial structures were raised, mostly of wood; and by the time that the Town was twenty years old, its buildings were sufficiently advanced to be described by the contemporary historian as “beautifull and large, some fairly set forth with Brick, Tile, Stone, and Slate, and orderly placed with comly streets whose continuall inlargement pressages some sumptuous City.” Hipped roofs were coming into vogue; and houses with “jetties”, projecting stories. At forty, the Town was showing a few of those three-story brick houses, broad-fronted, with arched windows, which are pictured as early colonial. Some of the few stone houses were of ambitious style and proportions. Notable was the “Gibbs house”, on Fort Hill, the seat of Robert Gibbs, merchant. “A stately edifice which it is thought will stand him in little less than £3000 before it be fully finished”, was Josselyn’s description in 1671 or thereabouts, when it was building. It was in this Gibbs house that Andros lodged on his first coming into the Town, and in it were quartered his guard of “about sixty red coats.” Grandest of all was the Sergeant house, on Marlborough Street, nearly opposite the Old South, set back from the thoroughfare in stately exclusiveness, the mansion of Peter Sergeant, a rich merchant from London, erected in 1679, and, after the opulent merchant’s death, bought by the Province, 1716, and becoming the famous Province House, official home of the royal governors. Before the middle of the Province period, prosperous Bostonians had begun erecting mansions of that finest type of American colonial, the great, roomy house, generally of brick though often of wood, with high brick ends, the few remaining relics of which in Salem, Newburyport, Portsmouth, fewer in Cambridge, so comfort the eye. These highly dignified Boston mansions were not infrequently set in spacious gardens, and surrounded with luscious fruit orchards, refreshing the town with their pleasant aspect. All long since disappeared. The distinctive Boston “swell front” was of the early nineteenth century, after houses in block began to make their appearance. Bulfinch, the pioneer native architect, was among the earliest of its builders.

The Market Place lay open through the Town’s first quarter century and more, the central resort for business or for gossip. In its third year, by order of the General Court, Boston was made a market town, and Thursday was appointed market day. At the same time the “Thursday Lecture” was instituted, the weekly discourse which was to play so prominent a part in the religious life of the Town for more than two centuries, — thus deftly welding trade with religion. So Thursday became the Town’s gala day. Then the country folk flocked into Town and to the Market Place and bartered their products for the wares of the Boston tradesmen, while the Lecture was taken in as a pious pastime. Early the market day became a favorite time for public punishments, for their disciplinary effects, perhaps, upon the “generality” of the populace. These spectacles customarily followed the Lecture, through which not unfrequently the wretched culprits must sit before undergoing their ordeal. Those instruments of torture, the whipping-post, the pillory, and the stocks, were placed conspicuously in the forefront, and the people gazed complacently — because such were the customs of the day in Old as in New England — upon whippings of women as well as of men, and sometimes of girls; upon the exhibition of women in the pillory with a cleft stick in the tongue, for too free exercise of this ofttimes unruly member. The show of a forger and liar bound to the whipping-post “till the Lecture, from the first bell”, when his ears were to be clipped off; the sight of whippings and ear cuttings, or nose slittings, for “scandalous speeches against the church”, or for speaking disrespectfully of the ministers, or of the magistrates were not unusual. Upon such or even worse scourgings for the pettiest of offenses as for graver crimes the good people were freely privileged to gaze. Nor were these punishments confined to the humbler classes. No discrimination was made between high and lowly wrongdoers. The local dry-as-dusts love to tell of that maker of the first Boston stocks who, “for his extortion, takeing Il 13s 7d for the plank and wood work”, was the first to be set in them. And there is satisfaction in reading of the case of one “Nich. Knopp”, who had taken upon himself to cure the scurvy by a water of “noe worth nor value, which he sold at a very deare rate.” Surely a fine of five pounds, with imprisonment “till he pay his fine, or give securitie for it, or els to be whipped”, and making him liable “to any man’s action of whome he hath received money for the said water” was none too rough for this scamp. Sometimes the woman with the scarlet badge on her breast may have been seen among the market-day gatherers. Here, too, unorthodox books were publicly burned.

Through these first thirty years of the Town, the Meeting-house stood beside the Market Place, serving for all Town and Colony business as well as for all religious purposes. At first it was a pioneer rude house of stone and mud walls and thatched roof set up on the south side (its site marked by a neat tablet above the portal of an office building) but lasting only eight years; then its more substantial successor of wood, placed on the Cornhill of the High Waye (in front of where is now and long has been Young’s, of savorous memories). Then in 1657—1659, the Town House — practically a Town and Colony House combined, of which the conserved Old State House is the lineal descendant — was erected in the heart of the Market Place, and in its stead became the business exchange and the official center. Thus the Market Place was in large part closed, and the square at the Town House front alone became the public gathering place. So the square remained the people’s rendezvous upon occasions of moment to the end of Colony and Province days, a central setting of what another Englishman with cousinly graciousness has termed “the great part” that Boston played “in the historical drama of the New World.”

How this first Town and Colony House was provided for in the longest will on record by worthy Captain Robert Keayne, the enterprising merchant tailor and public-spirited citizen, who became the richest man of his time in the Town, yet could not escape penalty and censure by court and church for taking exorbitant profits, is a familiar Old Boston story. Despite his disciplining by the very paternal government, the captain remained a Boston worthy in excellent standing and zealous in Town and Church affairs, till the end of his days. His memory is kept green as the father of the still lusty Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, the oldest military organization in the country, and father of the first Public Library in America, as well as father of the first Boston Town House, in which the making of large history was begun. Keayne indeed recovered favor by acknowledging his “covetous and corrupt behaviour.” But he closed, in his defense of it, with the offer of the business rules that had guided him; and much space in that prodigious will — one hundred and fifty-eight folio pages, all “writ in his own hand” — was devoted to a justification of his business conduct. Nothing more refreshing illustrates the business ethics of that simple day than this Puritan merchant’s defense and the minister’s offset to it. The rules that Keayne pled as guiding him were these:

“First, That if a merchant lost on one commodity he might help himself on the price of another. Second, That if through want of skill or other occasions his commodity cost him more than the price of the market in England, he might then sell it for more than the price of the market in New England.”

The minister, in this case John Cotton, would set up this higher code:

“First, That a man may not sell above the current price. Second, That when a man loseth in his commodity for want of skill he must look at it as his own fault or cross, and therefore must not lay it upon another. Third, That when a man loseth by casualty at sea etc., it is a lofs cast upon him by Providence, and he may not ease himself of it by casting it upon another for so a man should seem to provide against all providences, etc. that he should never lose 2: but where there is a scarcity of the commodity there men may raise their prices, for now it is a hand of God upon the commodity and not the person. Fourth, That a man may not ask any more for his commodity than his selling price, as Ephron to Abraham, the land is worth so much.”

Keayne had been a successful merchant tailor in London before coming out, and a London military man. He was for several years a member of the Honourable Artillery Company of London, after which the Boston company was modeled. He was made the first commander of the Boston company upon its organization on the first Monday in June, 1638 — the day that has ever since, with the exception of lapses in the Civil War period, been celebrated in Boston with all the old-time pomp and ceremony as Artillery Election Day. When he died, the year before the beginning of his Town house, he was presumably honored with a grand military funeral, and was buried beside the other fathers in the old First Burying-ground, which became the King’s Chapel. He was particularly associated with the Boston founders as the brother-in-law of John Wilson, the first minister and the personage next in consequence to John Winthrop and John Cotton in the early Town life. Their seats were nearly opposite, on either side of the Market Place. Keayne’s was on the south side, the comfortable house, the shop, and the garden occupying the ample lot between “Pudding Lane” — Devonshire Street — and Corn-hill. Wilson’s glebe, on the north side, facing the square, was an even more generous lot, extending back to the water of the Town Dock by Dock Square, and covering Devonshire Street north, which originally was a zigzag path from the Market Place to the head of the Dock across the minister’s garden. After the path had expanded into a lane, and had sometime borne the title of “Crooked,” it was given the minister’s name; and as “Wilson’s Lane” it remained to modern times when, with the extension of Devonshire Street through the ancient way, the good old colonial appellation was stupidly dropped. A century after Keayne’s day, the British Main Guard was stationed on the site of his seat, with its guns pointed menacingly at the south door of the present Old State House; and where Parson Wilson’s house had stood was the Royal Exchange Tavern, before which, and the Royal Custom House on the lower Royal Exchange Lane (now Exchange Street) corner, were lined up Captain Preston’s file at the “Boston Massacre.”

Keayne would have a Town House ample not only for the accommodation of the Town government, Town meetings, the courts, and the General Court, but also of the church elders, a public library, and an armory. But the sum that he bequeathed for his house and for a conduit and a market place besides, was only three hundred pounds. Accordingly subscription papers were passed among the townsfolk, and they contributed an additional fund which, with the legacy and a little aid from the Colony treasury, warranted the raising of a satisfactory structure. The townsmen being poor in cash, most of their subscriptions were payable in merchandise, in building materials, in a specified number of days’ work, or in materials and work combined. So this pioneer capitol duly appeared, completed in March, 1659, after a year and a half in construction, a “substantial and comely building”, and a credit to the Town and to its builders. Its erection marked an epoch in the Town’s history. The quaint pictures of it in the books are fanciful ones, drawn from the details of the contract, for no sketch is extant. It was a stout-timbered structure set up on pillars ten feet high, twenty-one of them, and jettying out from the pillars “three foot every way”, a story and a half, with three gable ends, a balustrade, and turrets. It was called the fairest public structure in all the colonies. The open space inside the pillars at first was a free market place. Later, perhaps, after its repair and enrichment at a considerable cost, which was divided between the Colony and the Town and County, parts were closed in for small shops; and the first bookstalls were here. In this open space, also, or on the floor above, was the “walk for the merchants” after the London Exchange fashion. At first ‘change hour was from eleven to twelve. After a time the custom was introduced of announcing the opening of ‘change by the ringing of a bell; and the bell-ringer was to be allowed twelve pence a year for every person commonly resorting to the place.

This comely capitol served the Town and Colony for half a century: through the remainder of the Colony period, the Inter-Charter period, and into the Province period. Here sat the colonial governors from Endicott to Bradstreet. Then came Joseph Dudley, as President of New England, with his fifteen councillors. Then Andros, as “captain-general and governor-in-chief of all New England”, till his overthrow by the bloodless revolution of April, 1689, “the first forcible resistance to the crown in America”, when the “Declaration of the Gentlemen, Merchants, and Inhabitants of Boston” was proclaimed from the balcony overlooking the square. Then Bradstreet again, now the Nestor of the old magistrates, in his eighty-seventh year, yet hale, sitting with the “council of peace and safety.” Then the earlier of the royal governors, under the Province Charter, beginning with the rough-diamond sailor-soldier Phips, when Boston had become the capital of a vast State, with the territories of Plymouth Colony, of Maine, and of Nova Scotia added to Massachusetts. And this was the Town House in which, in 1686, Randolph instituted, with the Reverend Robert Ratcliffe, brought out from London, as rector, the first Church of England church in Boston, when the authorities rigidly refused the use of any of the orthodox meeting-houses in the Town, now three, by the Episcopalians; but one of which — the Old South, then the Third — Andros speedily seized for their occupation alternately with the regular congregation. It was a place, too, of festivities, this Town House. Within it state dinners were given; and pleasing receptions to the visiting guest. John Dunton, the gossipy London bookseller, here in 1686, tells of being invited by Captain Hutchinson to dine with “the Governor and Magistrates of Boston”, the “place of entertainment being the Town-Hall” and the feast “rich and noble.”

Then, on an early October night of 1711, this house went down in ashes in a great fire — the eighth “great fire” which the Town had suffered in its short existence of eighty years — along with the neighboring Meeting-house, and a hundred other buildings, — dwelling-houses, shops, and taverns. The fire swept over both sides of Cornhill between the Meeting-house and School Street, and both sides of the upper parts of King and Queen streets. It was in this affliction that Increase Mather, the minister-statesman, saw the wrath of God upon the Town for its profanation of the Sabbath. “Has not God’s Holy Day been Profaned in New England!” he exclaimed in his next Sunday’s sermon, graphically entitled “Burnings Bewailed.” “Have not Burdens been carried through the Streets on the Sabbath Day? Have not Bakers, Carpenters, and other Tradesmen been employed in Servile Works on the Sabbath Day?” He would have stricter enforcement of the strict Puritan Sunday laws, which yet closed the Town from sunset on Saturday to sunset on Sunday against all toil and all worldly pleasure, permitted no strolling on street or Common, no cart to pass out or to come in, no horseman or footman, unless satisfactory statement of the necessity of the travel could be given. And this somber observance of Sunday continued to be enforced with more or less vigor till after the Revolution. There is a pretty, apocryphal tale of the fining of Governor Hancock for strolling along the Mall of the Common on his way home from church. But the selectmen of 1711 took the more practical step, in ordering the stricter enforcement of building regulations, and in influencing a reconstruction of the burnt district of brick instead of wood.

So, on the ruins of the old, arose a new Town and Colony House of brick, a new brick meeting-house, a new Cornhill of houses and shops, largely of brick. The outer walls of the new capitol, completed in 1713, we see in the present building. It was a grander house than the first. There was an East Chamber, with balcony giving on the square, handsomely fitted for the governor and council, a Middle Chamber for the representatives, a West Chamber for the courts; and in other parts comfortable quarters for the Town officers. The “walk for the merchants” was, as before, on the street floor, but more capacious; while ‘change hour was now one o’clock as in London. Pretty soon the exchange was surrounded by booksellers’ shops. These bookstalls, all having a good trade, together with “five printing-presses” in the Town, “generally full of work”, particularly impressed the Londoner, Daniel Neal, visiting Boston about 1719 and writing a book on his American impressions. By these, he flatteringly remarked, “it appears that Humanity and the Knowledge of Letters flourish more here than in all the other English Plantations put together; for in the City of New York there is but one Bookseller’s Shop, and in the Plantations of Virginia, Maryland, Carolina, Barbadoes, and the Islands, none at all.” Thus early were observed the evidences of that leadership in culture upon which the Boston of yesterday was wont much to plume itself.

Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market

This House stood in its grandeur, a “fine piece of building” as the observant Neal characterized it, for thirty years only. Then, in early December, 1747, it in turn was burned, all but its walls. Three years after, it was rebuilt upon and in the old walls, generally with the same interior arrangement, except the quarters for the Town officers, which were now in Faneuil Hall, erected Eve years before the Town and Colony House burning. In the interim, the General Court sat in Faneuil Hall; while the rebuilding of the Colony House in some place outside of Boston was agitated, or the Occupation of some other site in the Town, as Fort Hill or Boston Common. The present building therefore is that of 1749, with the walls of 1713. It stands restored in large part to the appearance it bore through the eventful fourteen years of the pre-Revolutionary period, when American history was making within it and, as John Adams recorded, “the child Independence was born.” Thus it remains the most interesting historical building of its period in the country. And it is to-day cherished, along with the other two spared monuments — the Old South Meeting-house and Faneuil Hall — that distinctively commemorate those colonial, provincial, and Revolutionary events which make Boston unique among American cities; these with King’s Chapel and Christ Church, are treasured by all classes of Bostonians with equal devotion as among the city’s richest assets. The sentimentalist treasures them for their historical worth, the materialist for their commercial value, their drawing capacity, luring to the Old Town as to a Mecca pilgrims and strangers of the prosperous stripe, from far and wide, with money to spend in the shops and the mart.

But ah! what a fight it was, what a succession of fights, to retain the richer in accumulated associations, — the old State House and the old Meeting-house! And so, too, hard fights were those to preserve in their integrity the other landmarks of the historic past that have been permitted to remain, — Boston Common, and the three ancient burying-grounds with their graves and tombs of American worthies. To-day let a promoter but suggest the cutting of streets through the Common to relieve the pressure of traffic, and straightway he is sprung upon by public opinion and threatened with ostracism. A mayor orders the taking of a part of the preserve for a public structure, and within twenty-four hours public opinion forces him to cancel the order. And yet it was not so many years ago that the opening of an avenue through its length connecting north and south thoroughfare, was contemplated with composure by many of those who like to be considered the “best citizens”, and the scheme was prevented only through the efforts of a small contingent of that kidney whom Matthew Arnold calls the “saving remnant”, who cultivated public opinion to revolt. As for the ancient burying-grounds, the desecrators years ago got in their work to a woeful extent before the preservers could act to check it. This was particularly the case with the King’s Chapel and the Granary grounds. Under the direction of a sacrilegious city official, to suit his peasant taste of symmetry, was committed that “most accursed act of vandalism” (so forcibly and justly the generally genial Autocrat characterized it), in the uprooting of many of the upright stones from the graves and the rearranging of them as edge stones by new paths then struck out. This is the act which moved the Autocrat to that clever mot, almost compensation for the sacrilege,—that “the old reproach” in epitaphs “of ‘Here lies’ never had such a wholesale illustration as in these outraged burial-places, where the stone does lie above and the bones do not lie beneath.” A later attempt to open a pathway across the King’s Chapel ground to accommodate passers more directly from Tremont Street to Court Square, proposed by restless city officials, and frankly as an entering wedge for the ultimate sale of the ground for business purposes, or the taking for an extension of the City Hall, was frustrated alone by the energetic protest of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The battle for the Old State House waged intermittently through forty years, or from the time of the building’s relinquishment as the City Hall, in 1841, the last official use to which it was put. During this desolating period it was hideously transformed for trade purposes that the city, whose property it then was, might get the largest rentals from it. Thus it stood a bedraggled thing at the entrance to the opulent center of money and stocks and bonds, a scandal to self-respecting Bostonians, while its demolition was repeatedly agitated as a useless incumbrance in the path of trade. In one of the periodical wrestles between conservators and destroyers when, with the adoption of a street-widening scheme, the building seemed surely doomed, the pride of Boston was touched by a breezy offer from Chicago to buy it and transplant it there, with the promise that Chicago would protect it as an historical monument “that all America should revere.” When at length, as in the case of the Common, through the quickening of public sentiment by the “saving remnant”, its preservation was secured, and its restoration had been in part accomplished, its integrity was assailed from an unexpected quarter. The local transit commission seized the street story and the basement for engineers’ working offices, and for a tunnel railway station. At this proceeding, the conservators rose to a final and determined move for the reservation of the building by law solely as a national “historic and patriotic memorial”, free of all business or commercial encroachments, and its maintenance as such. They got all they sought, except the ousting of the tunnel station. That, as we see, was permitted to abide, and so prevent complete restoration. Yet only to a comparatively slight extent. Except the lower part of this east end, and the foot passage through it, the building appears now fully restored to the outward and inward eighteenth-century aspect. Its occupation, as custodian, by the Bostonian Society, formed to promote the study of the history of Boston and to preserve its antiquities, an outgrowth of the organization of the little band that led fights that ultimately saved the building, is most felicitous. The society’s collection of Old Boston rareties, portraits, paintings, prints, manuscripts, mementoes, is rich and varied, and a half-day may be engagingly spent in a leisurely review of it.

The Faneuil Hall we see is the “Cradle of Liberty” of pre-Revolutionary days enlarged and embellished in the early nineteenth century to meet the requirements of later generations. It is the second “cradle”, erected in 1763 within the frame of the original structure of 1742, doubled in width and elevated a story, and its auditorium doubled in height and supplied with galleries raised on Ionic columns at the line of the old ceiling. Except in parts of the frame — and perhaps in the gilded grasshopper that tops the cupola vane — nothing remains of the house that Peter Faneuil built and gave to the Town, and that the Town in gratitude voted should be called for him “forever.”

That house, in January, 1762, when twenty years old, was destroyed by fire, all but its outer shell, like the second Town House burned fifteen years before; and also like it, its successor was built upon the remaining walls. The reconstruction of 1763, however, was practically a reproduction of the original edifice in style and proportions, so that in the present Hall we have traces of the architecture of the Faneuil gift. That structure was distinguished as the design of John Smibert, the Scotch painter, who, establishing his studio in the Town in 1729, was the earliest (if Peter Pelham, the engraver and occasional portrait painter, John Singleton Copley’s stepfather, is not to be so classed) to introduce good art in Boston with his portraits of ministers and provincial dignitaries. In the enlargement of the Hall of 1763, and the refashioning of its interior, in 1805, we see the hand of Charles Bulfinch, the pioneer native architect. The Faneuil gift was a handsome edifice, measuring only forty feet in width and a hundred in length, of two stories, the ground story for market use, with open arches, the auditorium above, low studded, the floor accommodating in public meeting a thousand persons. Small as it was, visitors pronounced it, as the Town vote of acceptance termed it, a “noble structure”, and a magnificent gift for the times from a single individual. Compared with Captain Keayne’s provision for the Town House a century earlier, it was counted princely. But Boston had now so grown in importance as to warrant such a gift, and it had a pretty number of affluent townsmen who could make a similar donation as comfortably as the generous Huguenot merchant. It was assumed to be the principal town of trade “of any in all the British American colonies.” The harbor was busy with shipping. Boston trade was reaching “into every sea.” Industries were prospering, regardless of the Parliamentary laws which would suppress colonial manufactures. Several of the merchants were enjoying rich revenues from productive plantations in the West Indies. Refinement and elegance were marking the homes and the customs of the “gentry.” “There are several families that keep a coach and a pair of horses, and some few drive with four horses”, wrote a Mr. Bennett, Londoner, in Boston about 1740.

Peter Faneuil was reveling in the fortune of his uncle Andrew fresh in his hands, when he made his offer to the Town. Andrew Faneuil had died in 1737, the richest man in Boston, and had bequeathed his handsome estate to his favorite nephew, who already had acquired considerable property through his own activity in business. Peter had moved into his uncle’s mansion-house, one of the fairest in town, and was stocking it with comforts and luxuries for his own enjoyment and the exercise of an elegant hospitality. “Send me five pipes of your very best Madeira wine of an amber colour, and as this is for my house, be very careful that I have the best”, he wrote to one of his business correspondents in London. To another, “Send me the latest best book of the several sorts of cookery, which pray let be of the largest character for the benefit of the maid’s reading.” Another was requested to buy for him for a house boy, “as likely a straight negro lad”, and “one as tractable in disposition” as his correspondent could find. And from London he ordered “a handsome chariot with two sets of harnesses”, and the Faneuil arms engraved thereon in the best manner, “but not too gaudy.”

The Faneuil mansion was on Tremont Street, opposite the King’s Chapel Burying-ground and neighboring historic sites. Just north of it had stood the colonial Governor Bellingham’s stone mansion, which he was occupying when first chosen governor in 1641, and the scene of dignified festivities. Next north of Bellingham’s was the humbler house of the great John Cotton and Cotton’s friend, debonair Harry Vane’s, which joined the minister’s house. The Cotton house and garden lot were south of the entrance to the present Pemberton Square; and the glebe extended back from the street and up and over the east peak of Beacon Hill, this peak then mounting abruptly and high, and given the minister’s name — Cotton Hill. The fair Faneuil mansion, built by the rich Andrew, about 1710, was a broad-faced house of brick, painted white, with a semicircular balcony over the wide front door, and set in a beautiful garden, with terraces rising at the back against the still remaining hill. Here Peter flourished, a generous host, a quietly beneficent citizen, an amiable gentleman, five luxurious years. Then he died suddenly, on the second of March, 1743, of dropsy, in his forty-third year. And as it happened, the first annual Town meeting in the new Hall was held to take action on his death, and to listen to an eulogy of him. His funeral was a grand one. He was buried in the Old Granary Burying-ground in the tomb of his uncle. This tomb was without inscription, marked only by the sculptured arms of the Faneuil family. The arms, after the lapse of years, failed to identify it, and where Peter was buried became a local query. At length, a delving antiquary rediscovered it, and the good man in simplest orthography inscribed it “P. Funel.” Peter’s pen portrait a contemporary diarist thus limned: “a fat, brown, squat man, and lame”, with a shortened hip from childhood. The same diarist recorded that the writer had heard “he had done more charitable deeds than any man yt lived in the Town.”

The rebuilder of the Hall after the fire of 1762 was the Town, aided by a lottery authorized by the Province. The new house was dedicated by James Otis, the patriot orator, he of the “tongue of flame”, to the “cause of liberty”, and this was the origin of its popular title of the “Cradle of Liberty.” The first Hall had also been dedicated to liberty by Faneuil’s eulogist, John Lovell, master of the Latin School, but this was qualified — “with loyalty to a king under whom we enjoy that liberty.” Had Faneuil lived, he might not have been so well disposed toward the second house, for the Town meetings were now growing hot, and his associates were of the Royalist party.

It was his friend, Thomas Hutchinson, with the Revolution to become an exile, that moved the naming of the original Hall for him. Master Lovell, his eulogist, went off with the British to Halifax. Several of Faneuil’s relatives also became refugees. A full-length portrait of him, which the grateful Town ordered painted and hung on the wall of the Hall, disappeared with the Siege. And the Faneuil mansion-house, which by 1772 had come the possession of a Royalist—that Colonel John Vassall, of Cambridge, whose mansion-house there became Washington’s headquarters and the after-day home of Longfellow — was confiscated.

Faneuil Hall was built on Town land, reclaimed from the tide, and when erected stood on the edge of the Town Dock and back of Dock Square. Over the dock in front of it a swing, or “turning” bridge connected Merchants Row from King Street with “Roebuck’s Passage” to North Street, and so to the North End. Roebuck’s, where now the north part of Merchants Row, was a lane so narrow, only a cart’s width, that teamsters were wont to toss up a coin to settle which should back out for the other, — or sometimes to tarry and argue the matter over their grog in Roebuck’s Tavern, which gave the passage its name. The dock remained open till after the Revolution, when a portion of the upper part was filled in; but it continued to come up to near the Hall till the Town had become the City. Then, in 1824, the first Mayor Quincy originated a scheme of improvement in this neighborhood, and in a little more than two years he had carried it through, against the persistent opposition of his municipal associates, whose breaths its stupendousness quite took away. Thus where the dock had been, rose the long, architecturally fine, granite Quincy Market House. Also were opened six new streets, a seventh was greatly enlarged, and flats, docks, and wharf rights were obtained to a large extent. And what was more remarkable, as civic enterprises go, this energetic, large-visioned Bostonian had the satisfaction of recording that all had been “accomplished in the center of a populous city not only without any tax, debt, or burden upon its pecuniary resources, but with large permanent additions to its real and productive property.” So Quincy’s name was added next to Faneuil’s in the list of Boston’s benefactors.

Dock Square behind Faneuil Hall became early a market center. Here was the Saturday night meat market of Colony days to which customers were summoned by the cheerful clanging of a bell. In neighboring Corn Court was the colonial corn market. A few years before the erection of Faneuil’s gift, the Town instituted a system of general market-houses, setting up three small establishments, the central one in this square, the other two at the then South End, bounded by our Boylston Street, and the North End, in North Square, respectively. At that time the townsfolk were sharply divided on the burning issue of markets at fixed points versus itinerant service, and in or about 1737 the central structure was pulled down by a mob “disguised like clergymen.” It was after this performance, and when popular sentiment appeared to be drifting toward the fixed system, that Faneuil made his generous offer to build a suitable market-house on the Town’s land at his own cost, on condition that the citizens legalize it and maintain it under proper regulations. But while the Town gave him an unanimous vote of thanks, the offer itself was discussed at an all-day town meeting, and finally accepted by the narrow margin of only seven votes. That Faneuil’s scheme originally contemplated a market-house solely, and the addition of a town-hall was an after suggestion of others, which was no sooner made than was cheerfully adopted by him, was greatly to his credit. And the unkind tradition that when the building was finished and the cost summed up, “Peter scolded a little”, does not detract from the merit of his beneficence.

The present bow-shaped Cornhill, picturesque with old shops and buildings, one or two reconstructed in colonial style, is an early nineteenth-century thoroughfare, primarily cut through to connect Court and Tremont streets more directly with Faneuil Hall and its market. Its projectors called it Cheapside, after London’s. In a little while, however, it took on the name of Market Street. Then a few years after the old Cornhill had disappeared with Marlborough, Newbury, and Orange, into Washington Street, it assumed the discarded, beloved name of the first link of the first High Waye through the Town. Early in its career it became a favorite place of booksellers’ shops; and the old bookstore flavor hangs by it still.