| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER X

ANOMALIES OF LIMA I THEY sat about the dinner table — a delightful, stammering, scientific gentleman, who advised my carrying home some live camarones (crayfish); a young English curate, here to sketch all the caterpillars of all the butterflies he could find, and their cocoons; the grandson of a former president of Peru, who spoke of his grandfather's battles; and a cousin of the actual president, who told tales of ostrich-hunting in the pampas of Argentina, a cosmopolitan club man, whose chief interests in Lima were cricket and polo. There was a man who was collecting everything from pearls to reduced heads and whose gold watch-fob was a Peruvian tongue-weight for the dead. A Chilean lady with the grace of an older generation spoke of the islands of Juan Fernandez and their prehistoric monuments, which have a nose and chin, face the sun, and are too big to enter the British Museum. That led toward the archeologist. We were eating cuculis — desert doves — and alligator-pear salad, while we listened to stories of pre-Inca civilizations from the man who has done most to unravel their mysteries. In Peru the alligator-pear is called palta, a shiny, dark-green, leather-covered shell concealing its soft, nutty flesh. It hangs at the end of a fine twig, which is dragged down by its weight. A stiff mayonnaise so disguises the palta that it is almost impossible to tell where fruit ends and sauce begins. A lady of mixed races wore twice about her neck a heavily-carved chain, on her breast the large cross at its end. She spoke of a friend who had searched for years until he should find a gift exactly suited to her; at last he beheld this chain about the neck of a pope of the Greek church. The pope parted with it reluctantly, for in a cavity in the back of the cross he kept his sacred relics. She twirled the great cross between her fingers. "Tres chic, n'est-ce pas?" she said. "And you see," touching the clasp to loosen a little lid, "it's just the size for a powder-puff!" A folk-lore-specialist-explorer was discussing swinging bridges in the Andes with a lady whose husband had left her in Lima while he took a distant journey in the interior to make a census of savage tribes. "What have you been doing to-day?" she asked. "Bless my soul, I don't remember," he replied. "Oh, yes! buying slaves in the jungle." Two young English people at the remote end of the table had just arrived in Lima from a honeymoon adventure up the Amazon. They had sailed as far as Iquitos; then they had paddled, they had ridden mule-back, they had tramped over the mountains, and, fording streams to their waists, had lain down in their wet clothes to sleep in the cold wind. We all inquired about fever. "Oh, yes," said the red-cheeked little lady, "my husband got the fever one day in Iquitos; it turned his eyes red and his face blue, and the whole house shook with his chills." He seemed to like to talk about their adventures. They had been paddling all one day, he said, and were paddling still, as night settled down upon the Amazon. Suddenly there was a whirring sound like a great cataract. "Paddle for your life," shrieked the guide, and swinging the canoe about, they fled down-stream. The whirlpool! Its encounter the greatest calamity that can befall a traveler upon the Amazon! No craft, however strong, once caught by the outermost edge of a whirlpool, can escape. Whether it is caused by a sudden squall brushing through the forest or a piece of the bank falling in, is not known. It is certain only that a whirlpool never occurs twice in the same place. "Death in that region," he went on, "is commoner than life. There is a horrible beast which the natives call a flying snake, with a blue head and a long prong upon it. It flies sting foremost. You are sauntering from your hammock to your cabin door. The thing flies against you, and presto! you fall with the poison of his contact, and another grave must be dug on the sposhy banks of the Amazon. "In Iquitos a woman bears a friend a grudge. She pays the police a small sum, and the next time her friend emerges, she is bound by the guardian of the peace, beaten until she falls, and is carried home to die. Prisoners there are allowed to order their own meals," he added. Then came stewed guavas, served with whirls of white of egg and pink and white pellets. II

Nearly everybody makes collections in Lima. In the ancient house of a marquis, with its court fountain, bougainvillea, and tall Norfolk Island pine, were benches of ebony with lower rounds worn into hollows by the feet of nuns; embroidered muslin stoles; queer manuscripts; tortoise-shell combs tall enough to be filled in with flowers; silver porringers; and a point lace parasol with a carved ivory handle — all relics of vice-regal days. One room was musty as seventeen mummies could make it. Fifteen soles, they told us, was the price of a mummy. There were ancient, inlaid chests filled with cases of butterflies from beyond the mountains, huge snake-skins, overgrown orioles' nests, necklaces of mummies' teeth, and carved cases of huacos dug from Yunca, grave-mounds — the pottery of mummies. Partly filled with water and rocked back and forth, the quaint things gave forth the same little half-whistle, half-sigh which notified their owners a thousand years ago that the precious water was being stolen. A soft bubbling, somewhere within the clay form, was supposed to imitate the voice of the animal painted on the outside. The liquids were meant to refresh a thirsty mummy on his death journey. He still holds his aching head. But the varnished lips were never parted, and the gurgling liquid of smoky flavor has never been sipped. These jars were the ephemeral tablets on which a whole people chose to leave records of itself. The work of their hands can be held in ours. We can look into the staring Indian faces or upon the weird animals which pleased them, shining under a glaze which is the forgotten accomplishment of those remote tribes. There are finely drawn portraits of the dead man's friends, whom he may have wished as fellow pilgrims, heads of men and women singing or smiling, some distorted with pain. The human face twisted to the same lines then as now. Wonderful fish glide among aquatic plants, the fox enamored of the moon languishes along her thin crescent. "The sneaking cat, the sleepy pelican, the supercilious, impudent parrot," in softest yellow, white, red-brown, or black, glance all the iris shades under a purple glaze. It was not enough to paint the manners and customs of the people, the fauna and flora of their country; they chose also to represent what they thought and believed as well as the adjustment of their sandals. We can peer into their monstrous, often loathsome, mythology and into their intangible land of fancy. Cats fight with griffins. A lizard with the face of an owl wears a jacket and bracelets. A chieftain in full regalia has a girdle ending in a fringe of almond-eyed, many-footed scorpions, each with a different number of feet. With snakes' heads as earrings, a warrior with canine teeth smaller than the snail with forked tongue beside him is fishing for an octopus with a snake-line, whose head, as bait, has caught a man. Crab-hands grasp from ears at a fleeing figure with a snakelike body, numerous feet intermingle with a human leg, two arms with nippers, and a fantastic head with waving antennae. A cactus forms the background. The sun looks forth from the heart of a starfish. A fanciful eye, all alone, with unknown appendages and impossible proboscis, glitters under its dark, lustrous sheen. A ghastly face with wings presides at a dance of stags. And here is a vessel completely covered by a pair of elaborated nippers! In it are placed some passion-flowers, a whirl of purple and black. Every uncanny suggestion in an animal is worked out to complete development. We may do the Yuncas the honor to call it allegorical. It recalls the Mexican legend that " the present order of things will be swept away, perhaps by hideous beings with the faces of serpents, who walk with one foot, whose heads are in their breasts, whose huge hands serve as sunshades, and who can fold themselves in their immense ears." It is primarily this portrait pottery which proves the great antiquity of races in Peru. And the deeper one digs, the finer the designs. Sitting on the ebony bench with the skin of a jaguar across its back, we ate dulces (sweets) made of eggs, and drank tea out of ancient porcelain against a background of embroidered Spanish shawls. A yellow bird, a cheireoque, who knows everything, sat upon a perch but did not sing. III

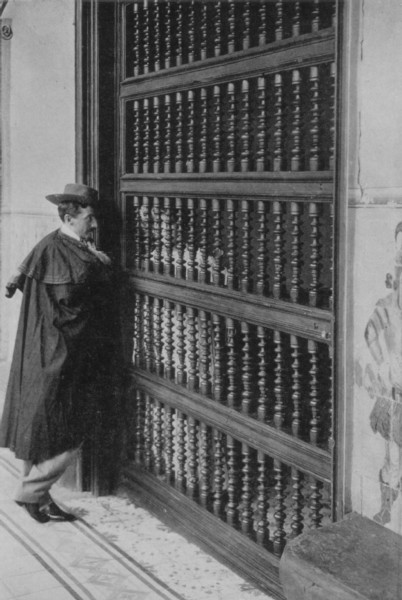

Ricardo Palma, Peru's delightful littérateur, has collected the national library since its destruction by Chilean soldiers in the late war. Storekeepers in those days wrapped up their goods in pages of " fathers of the church." The Chileans destroyed the annals of the Inquisition. They also killed the golden oriole which had sung in the trenches early one morning before the battle had begun. The distinguished writer of Peruvian traditions sat in his long gown, reading parchment tomes of bygone centuries, his silk cap pulled down to his eyes. I sat near him at a table surrounded by books under a far-away skylight. There happened to be open a volume of historical sketches of Limaneans done in color by Pancho Fierro: a man dressed for the gallows riding beneath balconies of interested ladies; monks and nuns in every garb; Indian dances with whirls of color; the Lord Mayor's procession with his big mace of silver, and black servants in green velvet holding a red umbrella. over his head; every known variety of eatable-seller; women with bright green trousers, whose veils covered them all but one eye, and uniforms of every profession and occupation. About the time when the Puritans were landing in Massachusetts Bay, a law was passed prohibiting ladies of Lima from covering the face. The animals of the coachman in whose carriage rode ladies violating this law would be confiscated, and any man who spoke to such a lady must pay a hundred pesos. But enforcement of the law was too difficult, and the custom of the veil persisted until a few years since. Don Ricardo turned and put into my hands a book of his own. The sun streamed through the distant skylight. I began to read: "Odoray is the most beautiful blossom of the flower garden of America, a white lily scented with the breath of seraphim. Her soul is an aeolian harp which the sentiment of love causes to vibrate, and the sounds which it exhales are soft as the complaint of a lark. "Odoray is fifteen years old, and her heart cannot leave off throbbing before the image of the beloved of her soul. Fifteen and not love — impossible! At that age love is for the soul what the ray of spring sun is to the meadows. Her lips have the red of the coral, the aroma of the violet. They are a scarlet line above the velvet of a marguerite. "The faint tint of innocence and modesty colors her face as twilight the snow of our cordillera. The locks of hair which fall in graceful disorder over the ermine of her shoulders, imitate the gold filaments which the Father of the Incas scattered through space on a spring morning. "Her voice is loving and feeling as the echo of the quena (flute). Her smile has all the charm of the wife in the Song of Solomon, all the modesty of prayer. Svelte as the sugar-cane of our valleys, if the place where it has passed can be recognized, it is not on account of the trace which its short plant leaves in the sand, but by the perfume of angelic purity which lingers behind. "It is an afternoon of April, 1534. Twilight sheds its undivided gleam above the plains. The sun taking off its crown of topazes is about to retire on the bed of foam to which the ocean entices it. Creation is at this instant a lyre letting fall soft sounds. The desirous breeze that passes giving a kiss to the jasmine, the petal that falls jostled by the wings of the painted humming-bird, the turpial that sings a song of agony in the aspen foliage, the sun that sets, firing the horizon... all is beautiful. The last hours of the afternoon and all things elevate the created toward the Creator. "To hear in the distance the soft murmur of the brook slipping along, to feel that our temples are brushed by the zephyr filled with the perfume which is exhaled by the flower of the lemon-tree and the rushy ground, and in the midst of this concert of nature"... such is the imagery of the literature of Peru.  A Glimpse of Old-Fashioned Lima IV

A woman in lilac called Dolores, a pretty woman with a vapid face, was absent-mindedly turning a green glass globe between her fingers and selling guavas. Young soldiers whose swords trailed along the pavement were eating the guavas. We got out of the carriage and rattled at a door until a keeper with jangling keys came to open it. The walls were spiked and covered with broken glass. The door banged together behind us. A thin, delicately featured man in a black silk cap and stock came forward in welcome. "The composer of Ollanta, the national opera," some one introduced. He led us toward a bare room scattered with manuscript music as fine as copper-plate. I looked at the iron bars across the windows. Over the piano hung three dusty laurel wreaths, the people's tribute to a genius they could not understand. After a three weeks' presentation by an uncomprehending Italian troupe, Lima demanded Mignon, and the manuscript opera was returned to the upper, right-hand drawer from which its composer now drew it. "I am transcribing the melodies of the Indians of the highlands, some of them survivals of Inca days," he explained. He played the weird, syncopated music of the Andes, bringing the indefinable "shiver of unknown rhythm," the wheedling love-songs and the sad yaravís which suggested those deep valleys lost among the mountain-tops. "You know the yaraví of the Indians? It is a peculiar music, a melancholy idyl reflecting the somber Indian character — a music of extremes, for no other is so dismal and so sweet. It wails in a minor key through strange Quichua words, the language of the Indians. "Many of these melodies I have used unchanged. Nothing so speaks to the spirit as they.... A secret music like that of falling water — one cannot hear it without thinking of the riddle of the world. It has a full, pent-up significance, as when a bird puts all the fervor of its song into pianissimo. It moves like the music of birds, and like it does not admit of criticism." I asked if the Indians sang unaccompanied. "There is sometimes a reed-flute accompaniment," he said, "as simple as the song. The flute is called a quena. Then, too, they play upon a pipe-of-Pan, supposed to have persisted since Inca days. But melody suggests to them things far lovelier than they can conceive by words. What they wish to say is made intelligible by the sadness or cheerfulness of the tune." There is a legend that a priest in early Spanish days loved a beautiful Indian girl who died. In desolation he mourned for years, until he dug up her skeleton and made a flute out of the big leg-bone. Then upon it he played weird, sad tunes and was comforted. This is the origin of the human-bone flute so widely used. "Have you ever heard of the 'Jug of Mourning?'" he suddenly asked. "Sometimes at evening the Indians play on flutes inserted in a large earthenware jar to make their tragic tones more resonant, and, sitting grouped around it at a little distance, they cry aloud and shed tears for the downfall of the race. The Indians' misfortune is infinite indeed, but a misfortune even their suffering is consistently monotonous." I asked about the libretto of Ollanta. "It is the only one of the great dramas dealing with exploits of kings, acted before the Inca by young nobles, still told by the people. Ollanta was a provincial governor who dared to love a daughter of the Sun and was commanded not to raise his eyes." "Have you had anything published?" I ventured. "This," he said, handing me an Elégie bearing a Paris publisher's mark. "Could I find it?" "Oh, no. It was out of print long ago.... Now I am working at Atahualpa, an opera. I consider it by far my greatest work; let me show you," and he took some loose leaves from a portfolio. He began to play again. His whole body swayed to the spectacular rhythm. There are occasions when rhythm is music, when melody is a refinement hardly necessary. Everything in nature keeps time to such a rhythm. Nothing can be indifferent. It turns a whole landscape theatrical. We were whirled up into the midst of the frenzied feather-dance, and beyond into a lofty sky where condors scarce can breathe. In the distance glittered the ice-cold puna cities. There is nothing I could not do if that thrilling moment could have been indefinitely prolonged! "But you are interested in seeing the boys at work, I feel sure," he broke in. The composer of Ollanta — sub-manager of a school of correction! "The boys are either bad or abandoned by their families at an early age. They are brought here and taught trades. They do all the work of the school. "Here is their swimming pool and their dormitory. In their schoolroom you will see object-lessons upon the walls, pictures of what will befall them if they are bad. "The worst thing they can do is to run away. They are put into prison when they return —here," and he unlocked a big door. There were four little doors on each side of a dark room. Those on the right opened into closets two feet wide and six long, with bars overhead, all painted black, "to keep them from writing on the walls," he explained. When the padlock was removed, the cubby-holes on the left were opened; two feet square, black. "Here they must stand." I gasped. "Oh, yes." "How long do you keep them in such a place? Surely not over night?" "Not more than eight days." "And in the other side?" "Not over ninety days in there." "Is any one in here now?" "Yes, two," he said. Certainly nowhere in Peru are contrasts more marked than in Lima of to-day, with its splendidly carved balconies of former times, its scavenger birds, and mud roofs strewn with ashes; its dim, candle-lit, incense-filled churches with their leper windows, and its international horse-racing; its collections of ancient, battered, gold idols, silver llamas, dishes and spoons, and its aeroplane called The Inca! Lima is a city where bull-fights are not only an amusement of the people, but of the finest and best intellects which the country has produced as well. Bull-fighters with queues, gold and silver embroidery, lace fronts, and red silk stockings are seen in the streets. Formerly the archbishop, religious orders, and monks all came to the bull-fights. The viceroy, shouting "Long live the King," threw a golden key into the bull cage, and the fight under most august patronage began. The market of Lima is a picturesque place: Chilean peppers (aji), orange and red, pats of goat's-milk cheese in palm leaves, unsalted butter in green corn husks, piles of ripe olives of various maroon hues, strawberries in hand-woven baskets. Fighting cocks glisten in the intense sunlight. Ladies in mantillas float by, closely followed by boy servants, their arms full of bundles. Here and there Franciscans with "sandaled feet and clattering crucifixes" are amassing tribute. There are said to be about six thousand ecclesiastics now in the city. Lima — with its botanical gardens, condors and llamas in cages, long allées of royal palms, and its cement tennis courts where English people are drinking tea; its venerable university, the oldest in America, and its aimless daily driving around and around the Paséo Colón; its proverbial milk-women in hand-woven shawls among shining cans perched high on ponies, and its craze for art-nouveau; its treasuring of Pizarro's bony remnant (which a guide explains is "completamente momificato") and its earthquake-rooms of solid masonry! Lima — where one discusses at some time or another everything from men-of-war to tapir-skin muffs! Lima — with its mediaeval festivals, when priests' chanting fills the streets, incense rises, blossoms fall, and candles twinkle in a ray of sunlight! As the old saying goes: "It were possible to die of hunger in Lima, but not to leave it." |