| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER V

A CLASH OF CONTRASTS I WHILE the mysticism of the Middle Ages was expanding in delicate spires of Gothic architecture, the Inca's empire was exposing its heart of gold to the blaze of a tropical sun. Their only similarity is that a shadowy veil, half history, half legend, floats between us and them both. But the gold shines through, and the veil cannot conceal its brilliancy. Once upon a time there was a garden of pleasure where flowers of gold opened from silver stalks, some full blown, others in close golden bud. Upon the walls crept strange insects and snails, so perfectly counterfeited in gold "that they wanted nothing but motion." Even the trees and the paths were of gold. Birds of gold perched upon golden boughs, their heads thrown back in silent song, and upon silver leaves gold butterflies poised in the sunlight upon their little golden feet. Hummingbirds of gold sipped imaginary honey from long, golden flower-bells. The old chronicler, Cieza de Leon, says that one garden "was artificially sown with golden maize, the stalks, as well as the leaves and cobs being of that metal; ...they were so well planted that even in a high wind they were not torn up; and besides all this they had more than twenty golden sheep with their lambs, and the shepherds with their slings and hooks to watch them, all made of the same metal." Near by were vast heaps of gold and silver, waiting to be wrought into wonderful shapes. The Inca ate within gold-lined walls, sitting "commonly on a stool of massive gold set on a large, square plate of gold which served for a pedestal." He ate from gold dishes rare viands from distant provinces, prepared in gold pots and kettles in a kitchen supplied with piles of golden fagots! He bathed in cisterns of gold in water conducted through golden pipes from distant springs. Francisco Lopez says: "Nay, there was nothing in all that empire (the most flourishing of the whole world) whereof there was not a counterfeit in pure gold." As hunger could not be satisfied with gold, it was valued only for its shining beauty, esteemed by the Incas' subjects only as a symbol of the Sun, those "tears which the Sun has wept." They naturally belonged to him. His worshippers even cast them into lakes, mirrors in which he looks upon his own reflected glory, and "sinks at last still gazing on it." The greatest of all Sun-Temples was Coricancha — the Ingot of Gold — where every implement in use, even to spades and rakes of the garden, was made of gold. Huayna Ccapac had learned from the god Uiracocha that a superior people would conquer the Incas and introduce a new religion. They would come after the reign of twelve kings; and "In me," he said, "the number of twelve kings is completed." Oracles had predicted their coming. And what was more significant, the great oracle of Rimac, "nothwithstanding its former readiness of speech, was become silent!" Omens had foreshadowed them. A brilliant comet "struck Atahualpa with such a dump of melancholy in his spirits that he remained almost insensible." A royal eagle pursued by hawks fell into the market-place of Cuzco and died. Great earthquakes shattered the shore, and tides did not keep their usual course. A thunderbolt fell in the Inca's own palace. Strange apparitions faltered in the air, terrible to behold. The Moon, mother of Incas, had three halos; the first blood-red, the second blackish, inclining to green, the third like mist or smoke. Atahualpa's atrocities had come to pass. For the first time civil war had decimated the empire of the Lover of the Poor, the Deliverer of the Oppressed. Such conduct had earned its reward. Was it not to be expected that the dawn-heroes of fair complexion, absent for a season, should reappear? Their vengeance was commissioned by the Light-god. What greater dramatic climax ever focused? What authority was ever more solidly founded? What identity of hero-gods more tangibly proven? A first appearance which further facts continued to corroborate. II

Lured by rumors of a descendant of the Sun in a city of gold, the first lean, poor adventurer, worn with uncertainty and suffering, stepped upon the shore of Peru. Pedro de Candia was his name, who, having burned ten cities, had dedicated in expiation ten lamps to the Virgin. His "coat of mail reached to his knees, his helmet of the best and bravest sort, his sword girt by his side. He took a target of steel in his left hand, and in his right a wooden cross a yard and a half long," advancing toward the Indians. Two fierce jaguars, "beholding the cross," fawned upon him and cast themselves at his feet. Taking courage at the sight, he laid it upon their backs and dared to stroke their heads. By virtue of that symbol a miracle had happened. Pedro de Candia and the Indians were equally dumbfounded. They followed him to the temples and palaces furnished and plated with gold and silver, all awed to silence, he at such magnificence in an undiscovered country, they at the sight of the tall, fair man, whose long beard hung down over his iron dress; all were convinced by this first encounter, the Indians of the divinity of the Spaniards, the Spaniards of God's patronage. "Being abundantly satisfied with what he had seen, he returned with all joy imaginable to his companions, taking much larger steps back than his gravity allowed him in his march toward the people." Eye-witnesses have described the Spaniards' first glimpse of Atahualpa, the red fringe shining on his forehead, when Hernando de ,Soto, the most daring of all Pizarro's followers caracoled upon his miraculous beast into the very lap of the dignified monarch. They feasted and drank chicha from goblets of gold which young girls presented to them, sitting upon seats of gold like the emperor's own. Two historians were present "who with their quipus (knots) made certain ciphers describing... all the passages of that audience." In Cajamarca, the Country of Frost, Atahualpa returned the visit. He came in full regalia, facing the pomp of a gorgeous sunset, and the Spaniards, "brandishing their pennants toward the flaring west, saluted with a great shout the Setting of the Sun!" First came multitudes of people clearing the way of stones and sweeping the road, then singers and dancers in three divisions, many richly dressed courtiers, and the guards, divided into four squadrons of eight thousand men, one before, one on each side of the Inca, and one in the rear. High on the shoulders of distinguished chiefs he rode upon a golden litter lined with brilliant feathers. His proud head, too large for his body, was encircled by the red fringe hanging above his wild and bloodshot eyes. Atahualpa, that courageous fiend who bragged that no bird flew in the air, no leaf fluttered on a tree without his permission, who though ransomed with a roomful of gold was taken prisoner in the midst of his own army by a handful of insolent adventurers, baptized in the Christian faith "Don Juan," bound to a post, and throttled like a common criminal! Pizarro put himself into mourning. The legend which had lured the Spaniards was proven true: that the land of a powerful king lay toward the south, where immeasurable treasure was amassed. It took a month to melt up the gold plaques and plates, brackets and moldings, statues of men, animals and plants, drinking and eating utensils, jars and jewelry of all sorts that filled Atahualpa's room of ransom. A huge quantity of gold, carried by eleven thousand llamas and intended for the ransom, never arrived. It is said to lie buried near Jauja, and is only one of the countless masses of hidden treasure, both along the coast and in the mountains, even into Ecuador. The Spanish messengers who were carried in hammocks to inspect that caravan on its journey toward Cajamarca were almost blinded by a mountain seeming to shine from base to crest with gold. The eleven thousand llamas had laid themselves down to rest. III

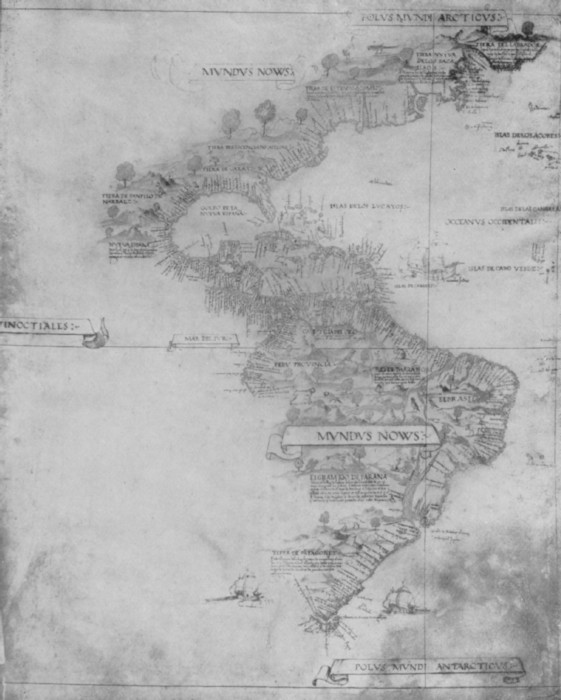

So they had come at last, the very image of the god himself, strange little Uiracochas in beards and ruffs; worthy of worship indeed, for they let loose thunder and lightning, the proper arms of the Sun, from instruments held in their hands, and rode about on amazing beasts. (The Indians' fear of horses persisting to this day, they are used only as infantry.) Were the Uiracochas insensible of hunger and thirst; did they need sleep after toil and repose after labor? Were they made of flesh and bones, or had they incorruptible bodies like those of the Sun and the Moon? So the grisly conquerors came, half heroes, half wild beasts, who did not grow exhausted by fighting, nor discouraged by wounds and the horrors of mountain-sickness. So they came, these few poor adventurers who fell upon a roomful of gold given them by a people in ransom for the sovereign-deity whom this handful of men had imprisoned. Miracles in their favor seemed to spring up at each step; and madly stimulated, the peaks of the cordillera blazing above them, their imaginations limitless, they strode through the empire in the guise of gods and scraped the sacred gold from the City of the Sun. They ripped the plate from the walls of its temples. They destroyed the idols. It is said that the Jesuits had to employ thirty persons for three days to break up a single carved stone huaco (idol). They dug up the treasures buried with the dead and pillaged the towns, and they brought back to greedy European sovereigns news of a land of gold. Having, as it seemed to them, found infinitely, they hoped infinitely and infinitely dared. The glittering career of the Indies had begun. No empire was ever won in so grandiose a way; no empire ever so monstrously destroyed.  Wolfenbüttel-Spanish Map, circa 1529 One of the first maps to show Pizarro's discoveries along the Peruvian coast. IV

Picturesque are the figures of the two great conquerors, Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro, lean and tireless soldiers, "either of whom, single, could break through a body of a hundred Indians," who amassed a fortune, the greatest that had been known in many ages, wasted it in wars with each other, and died so poor that they were "buried of mere charity." They dressed in the costume of their youth. The marquis "never wore other than a jerkin of black cloth with skirts down to his ankles, with a short waist a little below his breast. His shoes were made of a white cordivant, his hat white, with sword and dagger after the old fashion. Sometimes upon high days, at the instance and request of his servants, he wore a cassock lined with martins' furs which had been sent him from Spain," but his coat of mail was underneath, as appropriate to his body as its steely sheath to his heart. Illiterate, greedy, fearless, and proud, wading through blood to establish the Christian faith, he was murdered at last; and as he fell, traced in his own blood a cross upon the stone floor, kissed it, and died. Then there was the able monster, Carvajal, who went about accompanied by three or four negroes to strangle people. He jeered as they did so, "showing himself very pleasant and facetious at that unseasonable time." He left behind him a wake of spiked heads of "traitors" to the king. He wore a Moorish burnous and hens' feathers twined together in the form of a cross on his hat, bought masses with emeralds for his soul's repose, and at the age of eighty-four went to his execution in a basket, saying his prayers in Latin. "Being come to the place of execution, the people crowded so to see him that the hangman had not room to do his duty. And thereupon he called to them and said: 'Gentlemen, pray give the officer room to do justice.' " |