CHAPTER

VII

"MEN

OF HARLECH"

WHEN

Edward I. had

completed his so-called conquest of Wales, he safeguarded the

land he had won by building seven strong castles in seven

danger-spots. Those at Carnarvon and Conway we have already visited,

but most interesting of all is Harlech Castle, linked as it is with

the story of the far-off past as well as with the more modern history

of Wales.

Built

on a crag of rock

that juts from a terrace two hundred feet above the plain, stand the

great stone towers, looking towards the majestic range of Snowdon to

the north, and guarding the wide stretch of country below; while to

the west they gaze over the Irish Sea. Legend tells us that the

castle stands upon the site of a far more ancient building, Branwen's

Tower, which stood there a thousand years before English Edward was

heard of.

Bran

the Blessed was King

of Britain in those days, and with him in his fortress at Harlech

lived his sister, Branwen, the fairest maiden in all the land.

Now,

one day, says the

legend, Bran was at Harlech with his brothers and his followers,

and sat with them upon the great rock overlooking the sea. And as

they sat they saw thirteen ships coming from Ireland and making

straight towards them. Then Bran the Blessed raised himself and said:

"I see swift ships coming to this land. See that my officers

equip themselves right well and go to find out their errand."

So

the officers did so,

and when the ships drew near the shore, behold, they saw that they

were very richly furnished, with ropes of silk and flags of satin.

And in the foremost stood one who lifted a shield high above the

bulwarks, and the point of the shield was held upward in token of

peace.

Then

the strangers

landed, and when they had saluted the King, Bran from his rock said

unto them:

"Heaven

prosper you, my friends. To whom do these ships belong, and who

amongst you is your chief?"

And

they said: "Behold,

the King of Ireland, Matholwch, is here as suitor unto thee, and he

will not land unless thou grant him his desire."

"And

what is his

desire?" asked the King.

And

they said: " He

would make alliance with thee, lord, by taking in marriage Branwen,

thy fair sister; that, if it seem good to thee, the Island of the

Mighty might be joined to the Island of the Blessed, and so both

become more powerful."

"Let

him land,"

said King Bran, "and we will take counsel together upon this

matter."

So

the two Kings met in

friendly wise, and it was arranged that Matholwch should marry

Bran-wen, the fairest damsel in the land, and that the wedding should

take place at Aberffraw, in Anglesey.

There

a great feast was

held, all in tents, "for no house could contain Bran the

Blessed." But when the banquet was at its height, came in the

bride's half-brother, Evnyssian, and, out of spite, because he had

not been consulted in the matter, he went to the stables where the

horses of the Irish King had been housed, and "cut off their

lips to the teeth and their ears close to their heads, and their

tails close to their backs, and their eyelids to the bone."

In

his wrath, when he

discovered this, the Irish King would have broken off the alliance

and declared war there and then, but Bran managed to appease his

anger by giving him "a silver rod as tall as himself and a

plate of gold as wide as his face;" and so he sailed away to the

Isle of Saints with his fair bride.

But

he never forgot the

insult that had been offered him, for his people, jealous of the

strange Queen, were constantly reminding him of it; and after her

little son, Gwern b, was born, the King deposed her from her

place at his side, and ordered her to be cook in his palace.

Sad

indeed was Branwen,

for she was lonely in the land; but she reared a starling in the

cover of her kneading-trough, and when she had written down the story

of her wrongs, she tied the letter under the bird's wing, and set it

free. The bird, it is said, flew straight to Carnarvon, the abode at

that time of King Bran, perched upon his shoulder, and flapped his

wings till the letter was seen and taken from him.

Full

of anger at the

treatment his sister had received, King Bran called together his

fighting-men and embarked for Ireland. But Matholwch had no will for

warfare, and, having held converse with him, offered to make up for

the wrongs offered to his wife by giving up his crown at once to his

young son Gwern. To this Bran agreed, and forthwith the Irish King

ordered a great banquet to be prepared, that the contract might

be sealed.

Now,

the boy Gwern was

present at this banquet, and showed himself so lovable and so fair

that all admired him. But his wicked uncle, Evnyssian, who had

already wrought so much evil, waited till he came near, and then of a

sudden seized him by neck and ankles, and threw him into the great

fire that blazed upon the hearth. In vain did Branwen try to fling

herself into the flames that she might save her son. The deed was

done before she could grasp him, and his fair body had become a heap

of ashes.

Because

of this foul deed

did bitter warfare break out between the two countries, and so hard

went the fighting against the British that at length only seven

knights were left alive on the side of Bran, and he himself was

sorely wounded in the head, so that he was about to die. Then Bran

the Blessed commanded this poor remnant of his followers to strike

off his head and bear it to his native land, and he bade them keep it

at Harlech for seven years, and then to set it upon the White Mount

in the city of Lud; which place is now called Tower Hill in London

town.

So

the seven knights

returned to Harlech with the head of their King, and with them they

brought his sister, the unhappy Branwen. And on their way they rested

in Anglesey, where Branwen, looking first towards Ireland and

then towards Britain, cried with tears: "Woe is me that I was

ever born, for two islands have been destroyed because of me!"

Then

died poor Branwen of

a broken heart, and they buried her in Anglesey, at a spot known

henceforth as Ynys Branwen, "where a square grave was made for

her on the banks of the Alaw, and there was she laid."1

Early

in the last century

a four-sided hole was discovered by a farmer in this place, covered

over with coarse flagstones. Within was an urn, placed with its mouth

downwards, and full of ashes and fragments of bone. The urn was

certainly one of that period known as the Bronze Age, and belonged to

the "days before history," so we may not un-safely conclude

that the ashes it contained were really those of the unhappy Branwen,

sister of Bran the Blessed.

And

so we come back to

Harlech Castle, still with its Branwen Tower, built by Edward I. as a

bulwark against the "rebel Welsh."

In

later days Owen

Glendower besieged and obtained possession of the castle, and was in

his turn besieged there by Prince Henry. There it was that his

son-in-law, Mortimer, died, and there the wife and children of the

latter took, for the last time, refuge when the place was once again

captured by the English.

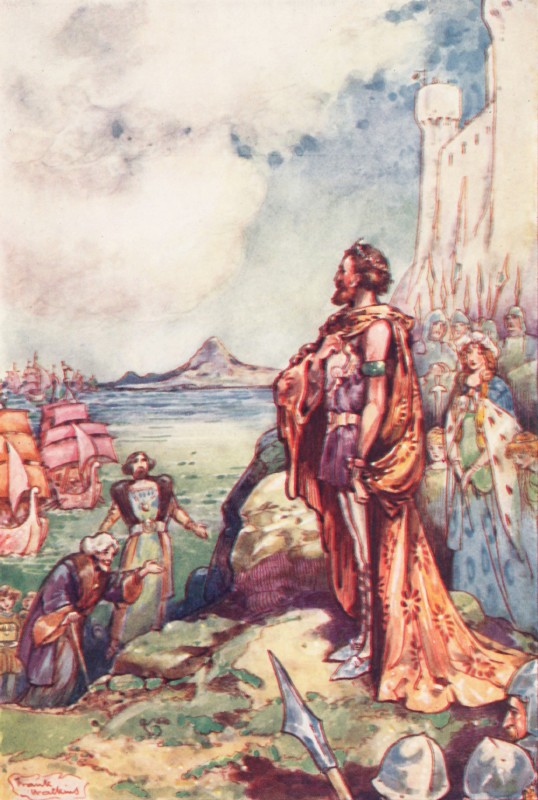

BRAN THE

BLESSED AT

HARLECH CASTLE WATCHING MATHOLWCH'S FLEET ARRIVE FROM IRELAND

The

Wars of the Roses

caused stirring times at Harlech. The castle was held against Edward

IV. by David ap Sinion, who had offered to receive there under his

protection Margaret, the unfortunate widow of Henry VI., and her

son, young Edward, after she had lost the Battle of Northampton.

Against

this "rebel"

marched Lord Herbert, who called upon David to surrender. But David

had done good work for the Lancastrian cause abroad, and he now

replied that "he had held a castle so long in France that all

the old women in Wales had talked about it; and now he was ğing to

hold Harlech so long that he would set the tongues of all the old

women in France wagging."

Great

was the slaughter

in that siege, during which, it is said, the "March of the Men

of HarIech" was written to stir the neighbouring vassal

chieftains to revolt against the usurping Edward.

"Fierce

the beacon

light is flaming,

With

its tongues of fire

proclaiming

'Chieftains,

sundered to

your shaming,

Strongly

now unite!'

At

the cry all Arfon

rallies,

War-cries

rend her hills

and valleys,

Troop

on troop, with

headlong sallies,

Hurtle

to the fight.

''Chiefs

lie dead and

wounded,

Yet

where first 'twas

grounded,

Freedom's

flag still

holds the crag,

Her

trumpet still is

sounded;

O,

there we'll keep her

banner flying

While

the pale lips of

the dying

Echo

to our shout

defying,

'Harlech

for the right!'

"

Even

in the English words

the chant is inspiring in the extreme; the Welsh words, joined to the

warlike tune, would stir the veriest coward to play his part like a

hero.

Sad

to say, the brave

David was forced at length to surrender, on condition that his life

was granted.

To

the honour of Lord

Herbert be it told that when Edward wished to put David to death he

sought him out, and demanded of him one of two things: either he must

send David back to his castle and despatch another officer to besiege

it, or he must take the life of Herbert himself in place of that of

the prisoner. Finally, the King forgave David, and Harlech, the last

to hold out for the Lancastrian cause, submitted.

1

From the "Mabinogion," according to the version in Rev. S.

Baring-Gould's "Book of North Wales."

|