CHAPTER

IV

A

WELSH MARKET-TOWN

WE have come to the end

of Glendower's story, but before we leave his part of the country

altogether let us pay a visit to Corwen, the old market-town that

lies so near his own valley.

Someone has said that

Corwen is "relentlessly tucked away under the dark shoulder"

of the heather-clad Berwyns, for above it lies the height of

Pen-y-Pigyn, which certainly keeps the sun off very effectually. In

the porch of the old church, indeed, we shall find a great stone,

called by a Welsh name that means "the pointed stone in the icy

nook." A legend, found in many other parts of Wales, says that

the builders vainly tried to erect the church, which was built before

the town, on a sunnier position farther down the valley, but every

night the walls were destroyed and the materials carried down to the

sunless spot under the hill.

Just above the vestry

door of that same church is a curious mark, said to have been made by

the dagger of Glendower, flung by him in a fit of rage one day from

the top of Pen-y-Pigyn.

So far away is Corwen

from mines or flannel mills or tourist centres, that it forms in many

ways a good example of a Welsh country-town, as it might have existed

not long after the days of Glendower himself.

The great interest lies

in the monthly fair-day, when the streets and market-place are full

of shaggy Welsh ponies, black-faced mountain-sheep, and cattle with

immense horns. At every corner stand groups of farmers, talking

eagerly with hands and shoulders as much as with lips, and with that

curious rise and fall of the voice which, they tell us, is the secret

of Welsh oratory. Of that conversation the Saxon from over the border

understands not a word; but no sooner does he make a remark than with

the utmost ease the Welshmen respond in excellent English. The power

of expressing themselves equally well in both languages is a striking

feature of even the most uneducated classes in Wales. Only here and

there in some farm hidden far away among the hills could one meet

with the experience of one who, weary and thirsty after a long tramp

over the high moors, approached a tiny farm-house and asked the old

woman who opened the door for a cup of milk. A shake of the head was

the only reply. "But you must have milk or water in the house!"

persisted the visitor. Another shake and a stream of words in an

unknown tongue followed. Not to be baffled, the Saxon raised his hand

to his mouth and made as if to drink.

With a cry of delight the

old dame rushed away, and returned with a large bowlful of liquid, of

which the traveller eagerly partook. It was fine thick butter-milk,

but, alas! it was quite sour!

Perhaps, however, the

chief regret in the visitor's mind was the impossibility of

explaining why the bowl was returned full to the brim, for the old

dame's puzzled look said plainly enough: "What more could the

stranger want than good Welsh butter-milk?"

Meantime the market-women

have spread out their goods—poultry, butter, eggs, and flowers—on

the market-stalls in a picturesque fashion enough. Many of the women

themselves are worth the attention of an artist, with their

strong brown faces, black crisp hair, and very dark blue eyes, "put

in with a smutty finger," as someone has well described them.

Fifty years ago you would

have seen them dressed in short red skirts, buckled shoes, crossed

bodices, and tall steeple-crowned hats worn over caps; but these,

unfortunately, have vanished.

The men—farmers or

cattle-drovers for the most part—differ in face more than they do

in name. To English ears everyone seems to be called either David

Mor-r-gan (with a beautiful roll to the "r")

or Owen Jones. But to the careful eye the difference between the

two original races is clear. The one is still short, smaller in

build, and very dark-haired; the other is tall, ruddy, with long

loose limbs and fiery red hair.

Borrow, whose amusing

description of his walks in "Wild Wales" you will like some

day to read, thus describes a fair at Llangollen some fifty years

ago, and from what one knows of these country-towns, one would not

expect to find things very different to-day.

"The fair," he

says, "was held in and near a little square in the south-east

quarter of the town. It was a little bustling fair, attended by

plenty of people from the country. A dense row of carts extended from

the police-station half across the space. These carts were filled

with pigs, and had stout cord nettings drawn over them, to prevent

the animals escaping.

"By the sides of

these carts the principal business of the fair appeared to be going

on—there stood the owners, male and female, higgling with

Llangollen men and women who came to buy. The pigs were all small,

and the price given seemed to vary from eighteen to twenty-five

shillings. Those who bought pigs generally carried them away in their

arms, and then there was no little diversion. Dire was the screaming

of the porkers, yet the purchaser always knew how to manage his

bargain, keeping the left arm round the body of the swine, and with

the right hand fast gripping the ear. Some few were led away by

strings.

"There were some

Welsh cattle, small, of course, and the purchasers of these seemed to

be Englishmen—tall, burly fellows in general, far exceeding

the Welsh in height and size....

"Now and then a big

fellow made an offer, and held out his hand for a little Celtic

grazier to give it a slap—a cattle bargain being concluded by a

slap of the hand—but the Welshman generally turned away with a

half-resentful exclamation.

"There were a few

horses and ponies in a street leading into the fair — I saw none

sold, however. . . .

"Now, if I add there

was much gabbling of Welsh round about, and here and there some

slight sawing of English—that in the street leading from the north

there were some stalls of gingerbread, and a table at which a

queer-looking being, with a red Greek cap on his head, sold rhubarb,

herbs, and phials containing I know not what—I think I have said

all that is necessary about Llangollen Fair."

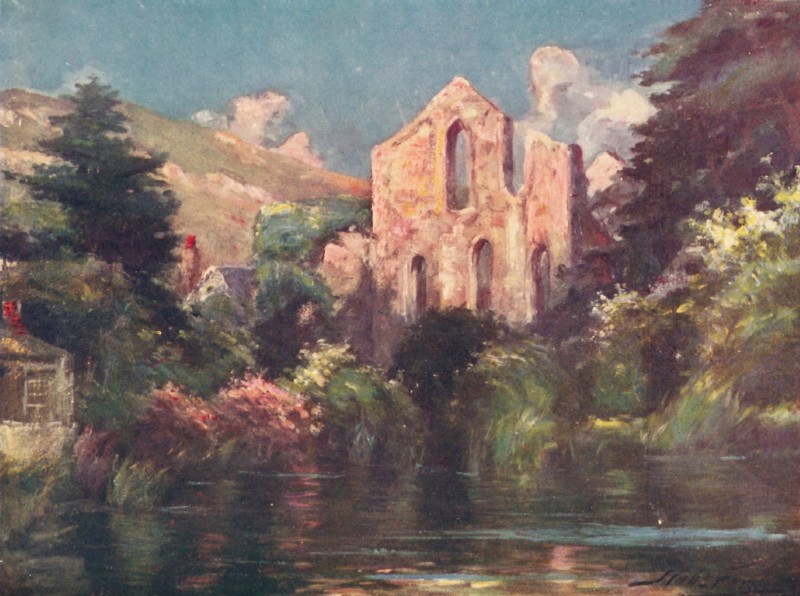

VALLE CRUCIS

ABBEY

Perhaps, however, we

should visit Corwen or any other Welsh market-town on a Sunday to see

the most striking characteristics of the people.

The streets are nearly

deserted, and a strange stillness broods over the place. At the open

door of some of the cottages an aged woman sits with a Welsh Bible on

her knees, and keeps an eye upon the toddling baby at her feet.

Everyone else has vanished, and not until a burst of melody sounds

from the plainly-built chapels which occur so frequently on the

highways and within the township, is their whereabouts revealed. Such

singing it is, too! It has been said that the Welsh people sing

naturally in parts, and certainly it seems as though nothing but

years of training would produce such a result with English choirs,

not to speak of a whole congregation, as is the case in Wales. In

perfect time and tune the beautiful old Welsh melodies ring forth,

and we begin to realize what a large part this hymn-singing and fiery

enthusiastic preaching plays in the daily life of this emotional and

deeply religious people.

|