CHAPTER

II

SNOWDONIA,

THE FASTNESS OF LLEWELYN

THE

story of the great

struggle of Wales for freedom under a Prince of her own is laid,

fitly enough, amid the wild scenery that surrounds the highest point

in Southern Britain. The whole district of Snowdon, with its grim

moorlands and towering heights forming a bulwark to the western

shore, breathes an air of freedom, and it was here that the last

Llewelyn defied the might of the first English Edward.

Roused

by the bitter

lament of those who had fallen under the yoke of the Anglo-Norman

barons, Llewelyn, Lord of Snowdon, threw off the pretence of alliance

and friendship which Henry III. had thought well to keep up between

them, and claimed to be ruler of all Wales, as his grandfather had

done in the days of Henry II. During the long Barons' War in England

the "Lord of Snowdon" found no difficulty in maintaining

his right to be "Prince of Wales"; the real trouble only

began when Edward I., on his accession, called upon the Prince to do

homage as his vassal. For two years Llewelyn paid no heed, and when

he heard that an English army was advancing upon him, went out

boldly to meet it.

But

the chieftains of

Central and South Wales turned traitor, his own brother David

deserted him, and the Prince, driven back to the inmost recesses of

his mountain fastness, was forced to lay down his arms. Preferring to

have him as friend rather than enemy, Edward behaved generously

enough, merely seizing a large slice of his dominions, confining him

to the Snowdon district, and providing that the title "Prince of

Wales" should cease at his death.

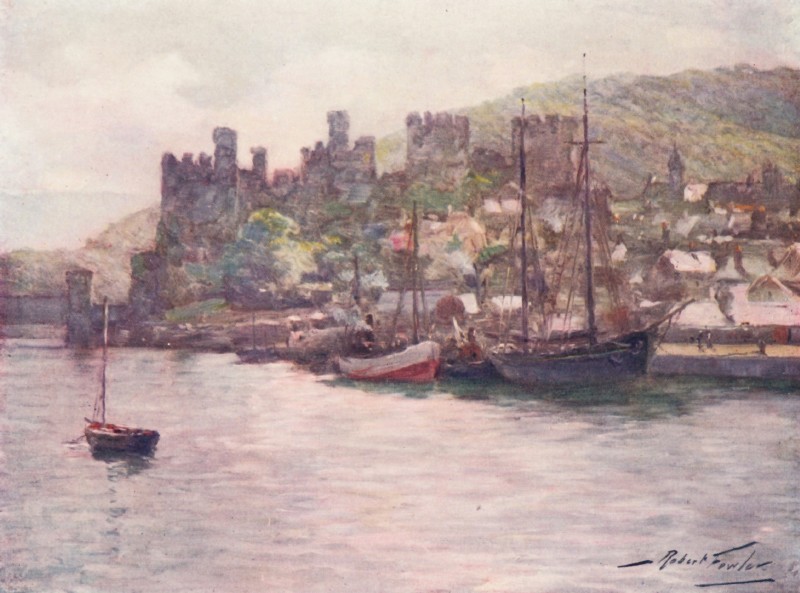

CONWAY CASTLE

Four

years elapsed of

outward peace and inward commotion. Then came a rumour of a strange

event. Long years before, Merlin, a famous Welsh bard and prophet,

had foretold that "when English money became round, a Prince of

Wales should be crowned in London." In 1282 a new copper coinage

had taken the place of the usual breaking of the silver penny into

halves and quarters; and in that same year the traitor David, who had

been rewarded with an English earldom, threw off his allegiance to

Edward, and appeared with an army before his brother's

dwelling-place. Gladly did Llewelyn once more raise the standard of

revolt, and a desperate struggle for freedom began. The great army of

the English King, encircling the Snowdon range, which was the

headquarters of the Prince, drew in closer and closer; but meantime

the English soldiers were suffering terribly in that hard winter of

1282, which the hardy Welshmen, living in the snowbound caves of the

mountain, seemed to pass through unheeding. As long as Llewelyn was

there to inspire and cheer, pain and even death were to be welcomed;

but almost by chance the men of Wales lost their leader in a quite

unimportant skirmish. Llewelyn had emerged from his mountain

lair, and, hoping to drive the English from the Brecknock district,

had ridden forth to meet some allies. He was met by a party of

English horsemen and cut down by an almost unknown knight. With

Llewelyn, "our last ruler," as the Welsh still call him,

the cause of Welsh independence was lost. At Rhuddlan, in Flintshire,

you may still see a bit of the wall remaining where the Statute of

Wales was passed by the Parliament held there in 1284; and in that

Statute Edward showed the greatest wisdom; for, instead of forcing

English laws and customs upon them, he allowed the Welsh to keep

their own as far as possible, altering them only where it was clearly

for their own advantage.

It

was at Carnarvon

Castle, which guards the entrance to "Snowdonia," that the

little Prince was born who was presented by Edward I. to the Welsh

chieftains upon a shield as a "Prince of Wales who could not

speak a word of English." And nowadays Carnarvon is, perhaps,

the best starting-point from which

to take a glimpse

of this wild and mountainous district.

Behind

us, as we look

towards the mountains, lie the Menai Straits, spanned by the fine

suspension bridge, so strong and yet so fairy-like with its arches of

Anglesey marble, that it has been called a " poem in stone and

iron." This bridge continues the Holyhead road to the island of

Anglesey, the home of the Llewelyns, where the soil is so fertile

that an old saying declares that it can provide corn enough for all

the people in Wales; and thence, across the island, we may reach

Holyhead, the starting-point for the Irish mail-boats.

Travelling

towards

Snowdon by rail to Llanberis, the scenery changes rapidly from pretty

woods and pastures to that of rugged heights, crags, and rockbound

lakes. The mountain valley in which the village lies is commanded by

the very ancient Welsh castle of Dolbadarn, once the prison of Owen,

the brother of the ill-fated Llewelyn, Lord of Snowdon. Below is the

great lake, and beyond the wild Pass of Llanberis, bounded by a

"tumultuous chaos of rock and crag, as if Titans in some burst

of fury had been rending cliffs and flinging their fragments far and

wide." If we are lazy, we may climb Snowdon by the little

mountain train, but if not, we set off the ascent till, just below

the steepest part, we turn off a little from the path to look at the

wonderful hollow of Cwmglas, high up in the mountainside, with

its two tiny tarns, surrounded by "striated" or

glacier-marked rocks.

A

steep scramble brings

us to the top of Snowdon, and if it is a clear day a glorious view

rewards us. Beyond the line of sea is the blue range of the Wicklow

Mountains in Ireland; below us, half hidden by the crags and

shoulders of the huge mass, lie lakes and valleys, and the quiet

lowlands stretching to the borders of the Atlantic.

Through

one of the

loveliest of these valleys we reach the mountain-girt village of

Beddgelert. You all know the story of Llewelyn and his faithful dog,

killed by his master because he thought he had eaten the child he had

in reality saved from a wolf. Here you may see the stones which mark

his tomb; but you will probably be told that the story is but a myth,

and that the grave is really that of a Welsh chieftain named Gelert,

and not of a dog at all. You may console yourselves with knowing

that, whether this is true or not, the picturesque little village was

a favourite hunting-spot for the Llewelyn whose story we know in

history, and that the curious little church there is part of one of

the oldest monasteries in Wales.

Another

beautiful valley

leads to the famous pass and bridge of Aberglaslyn. Here the huge

cliffs on either hand approach so closely to one another that

there is barely room

for road and river; and the wooded slopes, as they near the water,

afford a strong contrast to the wild rocks above.

After

this rugged

splendour, the prettiness of the Fairy Glen at Bettws-y-Coed will

seem tame enough. We will not linger there, but will finish our

glimpse of this land of Llewelyn by a visit to Conway Castle, built

by Edward I. in 1283, to safeguard this part of Wild Wales that he

had so hardly won.

"The

town of

Conway," rugged without, beautiful within," is a fine

example of the fortified walled towns of the Middle Ages. The walls

are triangular, and are said to represent a Welsh harp, and are

entered by crumbling stone gateways.

Above

them towers the

castle of Edward I., in which he was himself besieged on one occasion

by the rebel Welsh, and was only saved by the arrival of his fleet.

The

poet Gray makes this

neighbourhood the scene of an event upon which the light of history

throws grave doubt. The English King, believing that the conquest of

Wales would never be completed while the bards remained to stir up

the patriotic zeal of their fellow-countrymen, is said to have

ordered a general massacre of them on the banks of the River Conway.

It was the prophetic curse pronounced on the King by one of these

bards, standing "on a rock, whose haughty brow frowns o'er old

Conway's foaming flood," which

"Scattered

wild

dismay

As

down the steep of

Snowdon's shaggy side

He

wound with toilsome

march his long array."

In

spite of "Cambria's

curse and Cambria's tears," the English King must have felt

fairly secure within the massive walls of the castle, whose

banqueting-hall, now open to the sky, and ivy-grown, is of such noble

length and breadth that it might well have contained a regiment of

retainers. The passionate patriotism of Wales had little chance

against the solid strength of English builders and English troops.

|