| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Peeps at Many Lands: Modern Egypt Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

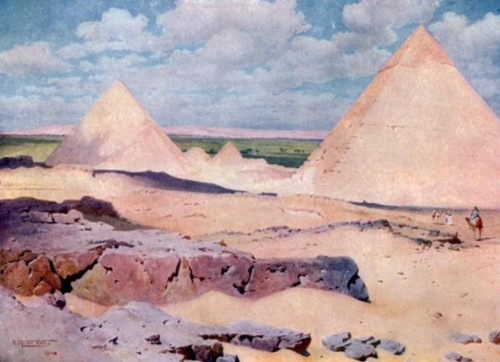

| CHAPTER VIII THE MONUMENTS If asked to name any one thing which more than any other typified Egypt, the average boy or girl would at once reply, "The pyramids," and rightly, for though pyramids have been built in other countries, this particular form of structure has always been regarded as peculiarly Egyptian, and was selected by the designers of its first postage stamp as the emblem of the country.  THE PYRAMIDS OF GHIZEH FROM THE DESERT. In speaking of the pyramids it is always the pyramids of Ghizeh which are meant, for though there are a great many other pyramids in Egypt these are the largest, and being built upon the desert plateau, form such a commanding group that they dominate the landscape for miles around. All visitors to Egypt, moreover, are not able to go up the Nile or become acquainted with the temples, but everyone sees the pyramids and sphinx, which are close to Cairo, and easily reached by electric car, so to the great majority of people who visit the country they represent not only the antiquity of Egypt, but of the world. The great pyramid of Cheops, though commenced in 3733 B.C., is not the oldest monument in Egypt; the step pyramid of Sakkara is of earlier date, while the origin of the sphinx is lost in obscurity. The pyramid, however, is of immense size, and leaves an abiding impression upon the minds of everyone who has seen it, or climbed its rugged sides. Figures convey little, I am afraid, but when I tell you that each of its sides was originally 755 feet in length and its height 481 feet, or 60 feet higher than the cross of St. Paul's, and that gangs of men, 100,000 in each, were engaged for twenty years in its construction, some idea of its immensity may be formed. At one time the pyramids were covered with polished stone, but this has all been removed and has been used in building the mosques of Cairo, and to-day its exterior is a series of steps, each 4 to 6 feet in height, formed by the enormous blocks of limestone of which it is built. Designed as a tomb, it has various interior chambers and passages, but it was long ago ransacked by the Persians, and later by the Romans and Arabs, so that of whatever treasure it may once have contained, nothing now remains but the huge stone sarcophagus or coffin of the King. The second pyramid, built by Chephron 3666 B.C., is little less in size, and still has a little of the outer covering at its apex. All around these two great pyramids are grouped a number of others, while the rock is honeycombed with tombs, and practically from here to the first cataract the belt of rocky hills which rise so abruptly from the Nile Valley is one continuous cemetery, only a small portion of which has so far been explored. Close by is the sphinx, the oldest of known monuments. Hewn out of the solid rock, its enormous head and shoulders rise above the sand which periodically buries it, and, battered though it has been by Mohammed Ali's artillery, the expression of its face, as it gazes across the fertile plain towards the sunrise, is one of calm inscrutability, difficult to describe, but which fascinates the beholder. From the plateau on which these pyramids are built may be seen successively the pyramids of Abousīr, Sakkara, and Darshūr, and far in the distance the curious and lonely pyramid of Medūn. These are all built on the edge of the desert, which impinges on the cultivated land so abruptly that it is almost possible to stand with one foot in the desert and the other in the fields. In addition to the pyramids, Sakkara has many tombs of the greatest interest, two of which I will describe. One is called the "Serapeum," or tomb of the bulls. Here, each in its huge granite coffin, the mummies of the sacred bulls, for so long worshipped at Memphis, have been buried. The tomb consists of a long gallery excavated in the rock below ground, on either side of which are recesses just large enough to contain the coffins, each of which is composed of a single block of stone 13 feet by 11 by 8, and which, with their contents, must have been of enormous weight, and yet they have been lowered into position in the vaults without damage. The tomb, however, was rifled long ago, and all the sarcophagi are now empty. There is one very curious fact about this tomb which I must mention, for though below ground it is so intensely hot that the heat and glare of the desert as you emerge appears relatively cool. While the Serapeum is a triumph of engineering, the neighbouring tomb of Thi is of rare beauty, for though its design is simple, the walls, which are of fine limestone, are covered by panels enclosing carvings in low relief, representing every kind of agricultural pursuits, as well as fishing and hunting scenes. The carving is exquisitely wrought, while the various animals depicted — wild fowl, buffaloes, antelopes, or geese — are perfect in drawing and true in action. Close to Sakkara are the dense palm-groves of Bedrashen, which surround and cover the site of ancient Memphis. At one time the most important of Egypt's capitals, Memphis has almost completely disappeared into the soft and yielding earth, and little trace of the former city now remains beyond a few stones and the colossal statue of Rameses II., one of the oppressors of Israel, which now lies prostrate and broken on the ground. Though there have been many ancient cities in the Delta, little of them now remains to be seen, for the land is constantly under irrigation, and in course of time most of their heavy stone buildings have sunk into the soft ground and become completely covered by deposits of mud. So, as at Memphis, all that now remains of ancient Heliopolis, or On, is one granite obelisk, standing alone in the fields; while at other places, such as Tamai or Bête-el-Haga near Mansūrah, practically nothing now remains above ground. In Upper Egypt, where arable land was scarce and the desert close at hand, the temples have generally been built on firmer foundations, and many are still in a very perfect state of preservation, though the majority were ruined by the great earthquake of 27 B.C. The first temple visited on the Nile trip is Dendereh, in itself perhaps not of the greatest historical value, as it is only about 2,000 years of age, which for Egypt is quite modern; but it has two points of interest for all. First, its association with Cleopatra, who, with her son, is depicted on the sculptured walls; and, secondly, because it is in such a fine state of preservation that the visitor receives a very real idea of what an Egyptian temple was like. First let me describe the general plan of a temple; it is usually approached by a series of gateways called pylons or pro-pylons, two lofty towers with overhanging cornices, between which is the gate itself, and by whose terrace they are connected. Between these different pylons is generally a pro-naos, or avenue of sphinxes, which, on either side, face the causeway which leads to the final gate which gives entrance to the temple proper. In front of the pylons were flag-staffs, and the lofty obelisks (one of which now adorns the Thames Embankment) inscribed with deeply-cut hieroglyphic writing glorifying the King, whose colossal statues were often placed between them. Each of the gateways, and the walls of the temple itself, are covered with inscriptions, which give it a very rich effect, their strong shadows and reflected lights breaking up the plain surface of the walls in a most decorative way, and giving colour to their otherwise plain exterior. Another point worth notice is that this succession of gateways becomes gradually larger and more ornate, so that those entering are impressed with a growing sense of wonder and admiration, which is not lessened on their return when the diminishing size of the towers serves to accentuate the idea of distance and immensity. One of the striking features in the structure of these buildings is that while the inside walls of tower or temple are perpendicular, the outside walls are sloping. This was intended to give stability to the structure, which in modern buildings is imparted by their buttresses; but in the case of the temples it has a further value in that it adds greatly to the feeling of massive dignity which was the main principle of their design. Entering the temple we find an open courtyard surrounded by a covered colonnade, the pillars often being made in the form of statues of its founder. This court, which is usually large, and open to the sky, was designed to accommodate the large concourse of people which would so often assemble to witness some gorgeous temple service, and beyond, through the gloomy but impressive hypostyle7 hall, lay the shrine of the god or goddess to whom the temple was dedicated and the dark corridors and chambers in which the priests conducted their mystic rites. In a peculiar way the temple of Dendereh impresses with a sense of mystic dignity, for though the pylons and obelisks have gone, and its outside precincts are smothered in a mass of Roman débris, the hypostyle hall which we enter is perhaps more impressive than any other interior in Egypt. The massive stone roof, decorated with illumination and its celebrated zodiac, is supported by eighteen huge columns, each capped by the head of the goddess Hathor, to whom the temple is dedicated, while columns and walls alike are covered with decorative inscriptions. Through the mysterious gloom we pass through lofty doorways, which lead to the shrine or the many priests' chambers, which, entirely dark, open from the corridors. Though it has been partially buried for centuries, and the smoke of gipsy fires has blackened much of its illuminated vault, enough of the original colour by which columns and architraves were originally enriched still remains to show us how gorgeous a building it once had been. There are a great many temples in Egypt of greater importance than Dendereh, but though Edfu, for example, is quite as perfect and much larger, it has not quite the same fascination. Others are more beautiful perhaps, and few Greek temples display more grace of ornament than Kom Ombo or submerged Philæ, while the simple beauty of Luxor or the immensity of the ruins of Karnac impress one in a manner quite different from the religious feeling inspired by gloomy Dendereh. I have previously spoken of the hum of bees in the fields, but here we find their nests; for plastered over the cornice, and filling a large portion of the deeply-cut inscriptions, are the curious mud homes of the wild bees, who work on industriously, regardless of the attacks of the hundreds of bee-eaters8 which feed upon them. Bees are not the only occupants of the temple, however, for swallows, pigeons, and owls nest in their quiet interiors, and the dark passages and crypts are alive with bats. There are many other temples in Egypt of which I would like to tell you had I room to do so, but you may presently read more about them in books specially devoted to this subject. At present I want to say a few words about hieroglyphs, which I have frequently mentioned. Hieroglyphic writing is really picture writing, and is the oldest means man has employed to enable him to communicate with his fellows. We find it in the writing of the Chinese and Japanese, among the cave-dwellers of Mexico, and the Indian tribes of North America; but the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt differed from the others in this respect, that they had two values, one the sound value of letters or syllables of which a word was composed, the other the picture value which determined it; thus we find the word "cat" or "dog" spelled by two or three signs which give the letters, followed by a picture of the animal itself, so that there might be no doubt as to its meaning. This sounds quite simple, but the writing of the ancient Egyptians had developed into a grammatical system so difficult that it was only the discovery of the Rosetta stone, which was written in both hieroglyph and Greek, that gave the scholars of the world their first clue as to its meaning, and many years elapsed before the most learned of them were finally able to determine the alphabet and grammar of the early Egyptians. I have said nothing about the religion of the Egyptians, because there were so many different deities worshipped in different places and at different periods that the subject is a very confusing one, and is indeed the most difficult problem in Egyptology. Rā was the great god of the Egyptians, and regarded by them as the great Creator, is pictured as the sun, the life-giver; the other gods and goddesses were generally embodiments of his various attributes, or the eternal laws of nature; while some, like Osiris, were simply deified human beings. The different seats of the dynasties also had their various "triads," or trinities, of gods which they worshipped, while bulls and hawks, crocodiles and cats, have each in turn been venerated as emblems of some godlike or natural function. Thus the "scarab," or beetle, is the emblem of eternal life, for the Egyptians believed in a future state where the souls of men existed in a state of happiness or woe, according as their lives had been good or evil. But, like the hieroglyphs, this also is a study for scholars, and the ordinary visitor is content to admire the decorative effect these inscriptions give to walls and columns otherwise bare of ornament. I must not close this slight sketch of its monuments without referring to the colossal statues so common in Egypt. Babylonia has its winged bulls and kings of heroic size, Burma its built effigies of Buddha, but no country but Egypt has ever produced such mighty images as the monolith statues of her kings which adorn her many temples, and have their greatest expression in the rock-hewn temple of Abou Simbel and the imposing colossi of Thebes. In the case of Abou Simbel, the huge figures of Rameses II. which form the front of his temple are hewn out of the solid rock, and are 66 feet in height, forming one of the most impressive sights in Egypt. Though 6 feet less in height, the colossi of Thebes are even more striking, each figure being carved out of a single block of stone weighing many hundreds of tons, and which were transported from a great distance to be placed upon their pedestals in the plain of Thebes.  THE COLOSSI OF THEBES — MOONRISE. Surely in the old days of Egypt great ideas possessed the minds of men, and apart from the vastness of their other monuments, had ever kings before or since such impressive resting-places as the royal tombs cut deep into the bowels of the Theban hills, or the stupendous pyramids of Ghizeh! 7 One with a roof supported by columns. 8 A small bird about the size of a sparrow. |